‘Famous then forgotten’: can Frieze rescue the legions of lost female painters?

Their work dazzled the world – but was obliterated from history. As the giant art fair Frieze opens in London, we explore its historic new section aiming to write women back into the story of art

Amy Fleming

Tuesday 10 October 2023

Down a leafy mews in Montparnasse where the windows and doorways are heavilyfringed with vines, you can still find a tantalising hint of old Paris. Villa Vassilieff is where the Russian-born painter Marie Vassilieff, who studied with Matisse, opened an art school and a canteen to feed the city’s cash-strapped artists – who at that time included Giacometti and Picasso.

These days, her former premises are fittingly occupied by a group of feminist art historians called Aware (Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions), whose aim is to rewrite female-identifying artists back into the story of art. One indication of how effective Aware’s first nine years have been is the historic new section they have curated for the art fair Frieze Masters, which opens this week in London. Modern Women features artists active between 1880 and 1980, a time span chosen to encompass the first and second waves of western feminism.

The show includes a formidable range. There is work from the 92-year-old African American feminist artist Faith Ringgold, who in the late 1940s had to fight and compromise to be accepted on to an art degree course. In a 1994 piece called The French Collection Part 2: #11, Le Café des Artistes, she painted a fictional black woman proclaiming to a crowd of eminent artists: “Modern art is not yours or mine. It is ours.” There is also a section highlighting how 20th-century women reclaimed the female nude.

“After the first world war, a lot of artists in Paris, London and Berlin represented nude portraits completely differently,” says curator and Aware director Camille Morineau. Many of them were lesbian or bisexual, “and were not objectifying a woman’s body”. There’s a dreamy 1920 portrait of the writer Colette reclining on her stomach like the cat that got the cream. This was painted by Émilie Charmy – “probably her lover” – who was part of the Fauvist group with Matisse. Morineau describes Charmy’s nudes as “very liberated, with women masturbating - an erotic lesbian gaze”.

Another of the nudes in the show was painted by the English artist Dame Ethel Walker in 1936. “She was really famous in England,” says Morineau, “while also openly living her homosexuality.” What sets the idealised bodies in her painting apart from traditional eroticised nudes, says co-curator Eléonore Besse, is that each woman is presented as an individual with distinct physical features, and “the central figure in particular is represented with a poignant interiority”. Walker, who was close to Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury set, represented Britain four times at the Venice Biennale and was a classic example, says Morineau, “of being very famous in her lifetime and then forgotten, like many women artists”.

The impetus for Aware came when Morineau was working at the Pompidou Centre in 2009 and curated a show of women artists in the permanent collection. “It lasted two years and we had 2.5 million visitors,” she says. Many of the artists had been unfamiliar to her and she was “struck by the fact that not only were these women artists fantastic and interesting, but there was very little information on their work and on their lives”. While working on the show, Morineau made a website about all 300 artists, featuring interviews and an interactive chronology. “I wanted to create a research centre within the Pompidou Centre, to continue producing information about women artists. But at the time I was working on shows of famous male artists – Gerhard Richter and Roy Lichtenstein – and I felt that this research centre would not happen easily”.

Painfully aware that the value of an artist’s work directly correlates with how much of their story is known, Morineau took a huge risk in 2014 and left her job at the Pompidou Centre to start Aware as a non-profit organisation. “I had a job in a great museum, which I left for something unknown, for which I had to raise money for my own salary,” she says. “A lot of people think that I’m rich or I could afford it, but I really couldn’t. I was a widow raising two young children. So it was a really difficult decision to make – and a political one.” Sponsorship from the fashion house Chanel was instrumental in getting Aware off the ground – an apt match given its founder, Coco Chanel, gave short shrift to gender rules in the early 20th Century. The French government now provides about 20% of Aware’s budget, with other sponsors also involved.

Morineau has a permanent team of three in Villa Vassilieff, working alongside various equally devoted freelancers and interns. A library is housed there and, rather charmingly, Morineau works from a room above the loft space that once housed Vassilieff’s canvases: a proper light-filled artist’s garret, preserved as such so that nothing as practical as double-glazing is allowed, and even petite women must duck to enter. Aware’s influence now reaches all over the planet, from the US to Africa and south-east Asia, from where local research is fed back, exhibitions are created and partnerships forged for projects with museums such as the National Portrait Gallery in London. “And I see all these books now published using free information on the website. It is very rich information and I’m very proud of that.”

Female artists’ stock is rising. At last year’s Frieze Masters, Frieze director Nathan Clements-Gillespie had asked Aware to curate the Spotlight section, which he says was a great success. “Works were acquired by the Tate gallery for the national collection. We had a work acquired for the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.” Among the high-value sales at Frieze Masters 2022, he says, was a piece by American surrealist Dorothea Tanning fetching around £950,000. “I think one of the most important things is compiling and publishing biographies and allowing people to find out more about the artists,” he says. “And certainly with Frieze Masters, we always aim to broaden our own, but also our public’s understanding of art history by creating these specialist sections that give prominence to figures whose work may have previously been overlooked by the canon.”

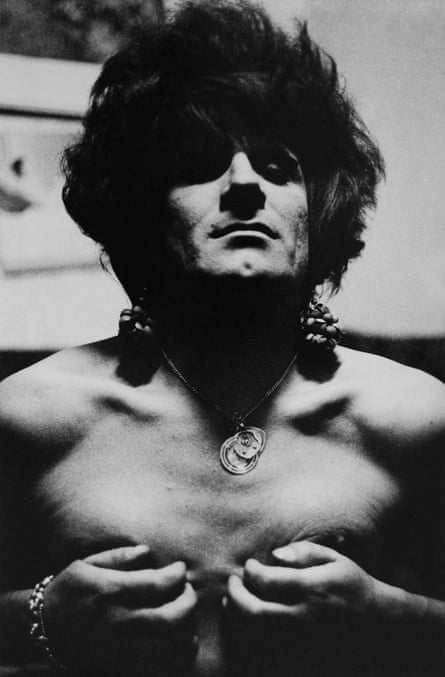

Prominent in this year’s show, says Morineau, is “gender fluidity or pre-queer thinking. We’re really trying to pursue the idea that what we call queer or LGBTQ+ today, was really invented or thought about a century before.” Italian photographer Lisetta Carmi, who died in 2022, would have been 100 this year. “She did an amazing series of work in 1964 about the Italian LGBTQ+ community,” says Morineau. “Her book I Travestiti, which she worked on between 1965 and 71, was really one of the first photography series on transgender people.”

There’s also a section on abstraction – which for female artists was a way to be gender neutral. Morineau describes two strongly contrasting examples. The first, Tarsila do Amaral, brought the Paris avant garde back to her native Brazil. To be more precise, says Morineau, her paintings are “quasi abstract. She distorted figures so they would become abstract, and this invention created the first modernist movement in Brazil.”

Then there’s Vera Molnár, a Hungarian artist who moved to Paris and became a pioneer in beautiful and mind-boggling computer art. Her geometric paintings and drawings “come from what was the ancestor of computers in the 1940s and 50s,” says Morineau. “She based her work on computer programs. And she’s still living – she’s going to be 100 in January.” But, says Matylda Taszycka, head of the scientific programs at Aware, she didn’t want to “completely abandon the principle of randomness, and deliberately injected ‘1% of disorder’ into the systems she created.”

The uniting theme running through Modern Women is that these female artists had been famous during their lifetimes. “With the exception,” says Morineau, “of maybe Lisetta Carmi who was famous but not for good reasons. She created controversy: I Travestiti was difficult to look at at the time.” Most of the others were celebrated with retrospective exhibitions and yet, she says, “they have been sort of forgotten – and that’s really the big question about female artists. I would say 80-90% of them, even if they have been famous, they have at some point been forgotten. The purpose of Aware is to work on this visibility.”

No comments:

Post a Comment