A Basic Guide to Japanese Etiquette

“Seiza” and Other Japanese Ways of Sitting

Seen in formal situations like Buddhist prayer services or the tea ceremony, the traditional seiza way of sitting can be quite demanding. Here we introduce its history and related etiquette, as well as other ways of sitting in Japan.

How to Sit on the Floor?

Japanese have long observed the custom of removing footwear inside the home and lowering themselves to sit on wooden floors or tatami mats.

Although chairs were gradually introduced during the Meiji era (1868–1912), up until the 1980s families usually gathered around a low table to eat or relax on tatami. Even today, at temples and some restaurants, people remove their footwear at the entrance before moving inside and sitting on the floor. Many foreign visitors, particularly those accustomed to sitting on chairs, have been left perplexed about the proper manner of sitting on the floor.

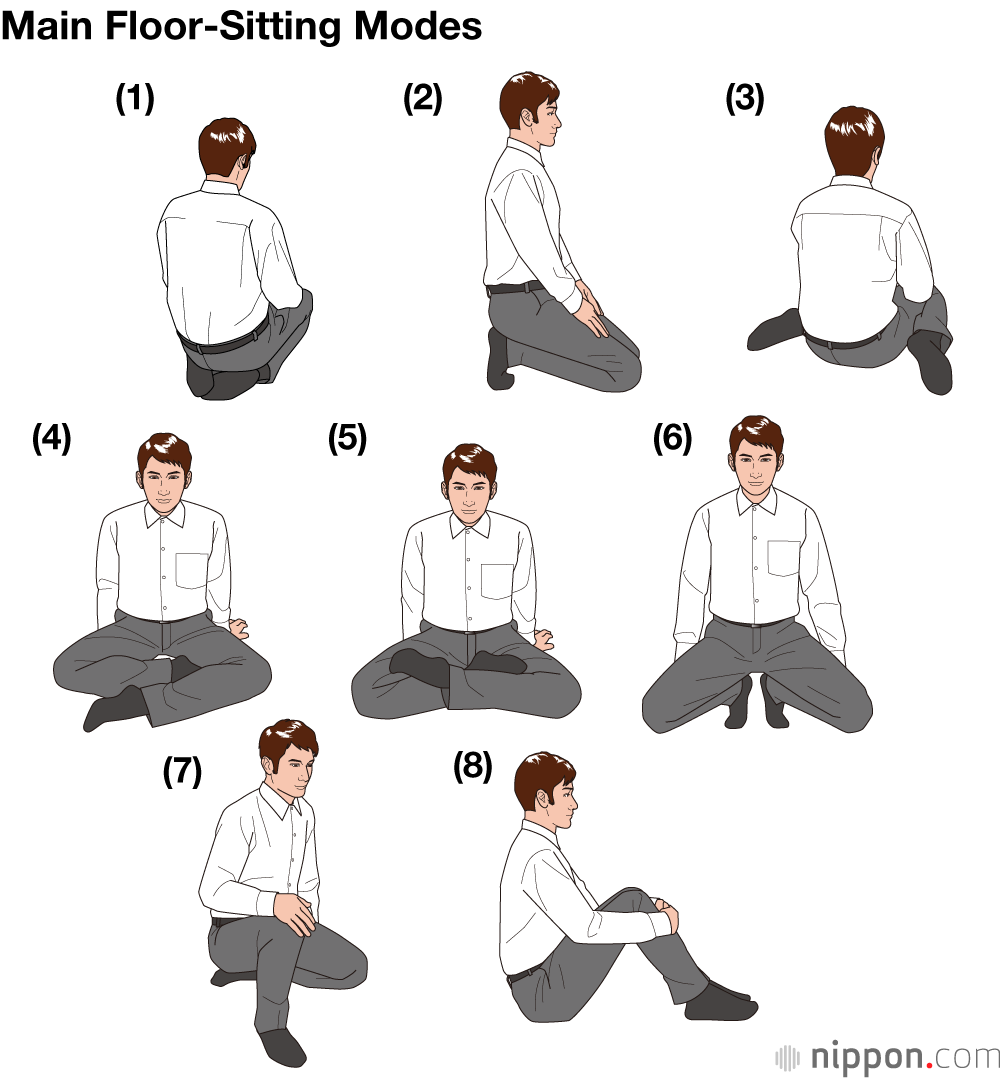

The following illustrates the main modes of floor sitting.

- Seiza: kneeling and resting the posterior on ankles and heels.

- Kiza: raising the heels while in seiza posture and balancing on toes and knees.

- Wariza or kamei: from seiza posture, splaying the legs to the left and right in the shape of an “M.”

- Agura: crossing the legs in front of the body. When the legs are crossed loosely, the posture is called anza.

- Kekkafuza: Crossing the legs and bringing the heels up to the opposite thighs. This is the sitting mode used for zazen meditation.

- Sonkyo: Squatting while balancing on the toes. When the heels are lowered onto the floor, it is also called the “toilet squat.”

- Tatehiza: Standing one knee and folding the other under oneself.

- Taiiku-zuwari or sankaku-zuwari: Sitting with one’s posterior on the floor and knees raised, with hands on knees or around the legs.

Japanese sit in many different ways. They may sit cross-legged or with the legs to one side of the body, styles that non-Japanese are familiar with too. During school physical education classes, sitting with the knees raised and the posterior on the ground in the position called taiiku-zuwari or “PE pose” is relatively comfortable.

Elementary schoolchildren sit in the taiiku-zuwari style in the schoolyard or the gym. (© Pixta)

In sumō and other martial arts, sonkyo is an expression of gratitude. Here, yokozuna Hakuhō ( now retired) is pictured entering the dohyō ring on March 23, 2016. (© Jiji)

Seiza is the most demanding way of sitting, which even many Japanese find difficult. With knees bent under and the weight of the upper torso resting on calves and heels, blood circulation is impaired and the legs go numb. Even so, participants are expected to sit seiza on formal occasions like Buddhist prayer services or the tea ceremony.

As the convention of seiza is inculcated from childhood, Japanese accept that their legs will fall asleep as a matter of course. But non-Japanese may wonder why what they view as a form of self-torture is the “correct” way of sitting.

If your legs go numb while sitting seiza, shifting to the kiza posture can bring blood circulation back. (© Pixta)

“Pins and Needles” As A Form of Control

Through until medieval times, it was customary to sit cross-legged or with one knee raised, even on formal occasions. Seiza seems not to have been widely practiced; in those days, it was known as kiza (although written with a different kanji to the style introduced in the illustration above).

Paintings depicting court nobles or warriors often show them sitting with the soles of the feet touching together. Called rakuza (comfortable pose), this way of sitting may not strike modern folks as especially easy to assume. (Copy of an original painting of Oda Nobunaga at Tokyo National Museum. Courtesy ColBase)

In the past, criminals were made to sit in seiza mode for long stretches. This was a form of torture meant to induce them to confess or express remorse and may be why today a person will sit seiza while being lectured or conveying an apology.

An Edo period (1603–1868) court where those being tried knelt seiza-style on gravel. From Tokugawa keijizufu (An Illustrated Reference Book of Tokugawa Criminal Cases) (Courtesy the Meiji University Museum)

It was the Tokugawa shōguns who, bringing peace to the country following a century of wars, made seiza the “proper” way of sitting, apparently for the purpose of rendering those with whom they were having audiences harmless by having their legs go numb. No one sitting seiza for an extended period would be able to stand up immediately; this offset the possibility of a sudden assault on a higher-up. On the part of the sitter, seiza, indicating no intention of fighting back, was also a means of showing respect or obedience toward the shogun, a shogunate vassal, or a superior.

Seiza was imitated by wealthy merchants taking part in the tea ceremony or other social interactions with the samurai class. It also gradually filtered down to townspeople as a means of expressing respect to someone of higher social status. Seiza had the additional benefit of improving posture, as it naturally straightens the spine.

Kneeling in prayer is an action seen throughout the world, but seiza as a means of showing respect may be unique to Japan. This aspect of samurai etiquette was born from the more than 250 years of peace established by the Tokugawa shōguns.

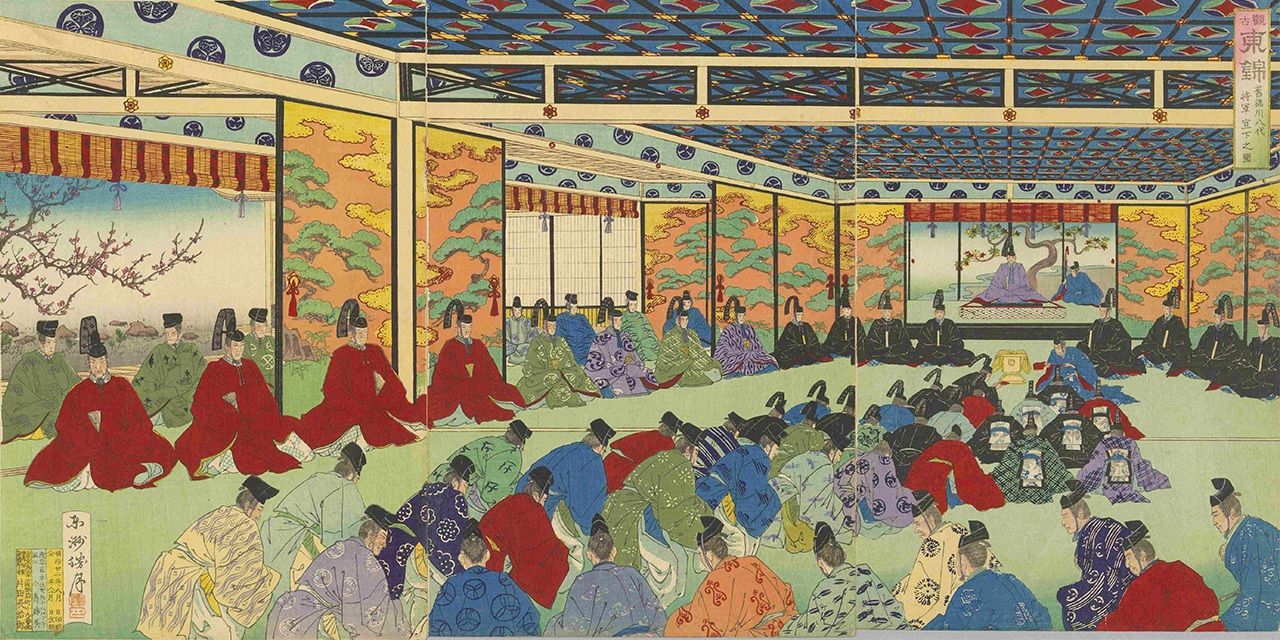

The scene at Tokugawa Yoshimune’s accession ceremony as eighth Tokugawa shōgun, in Kanko azuma nishiki: Kyū Tokugawa hachidai shōgun senge no zu (Colored Woodblock Print of the Declaration of the Eighth Tokugawa Shōgun). (Courtesy the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room)

The scene at Tokugawa Yoshimune’s accession ceremony as eighth Tokugawa shōgun, in Kanko azuma nishiki: Kyū Tokugawa hachidai shōgun senge no zu (Colored Woodblock Print of the Declaration of the Eighth Tokugawa Shōgun). (Courtesy the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room)

Tatami and Zabuton

The culture of tatami, woven mats softer and warmer than wooden floors, also played a major role in propagating seiza. Initially seen only in the homes of nobles and samurai, tatami had become a fixture in the dwellings of townspeople by the early eighteenth century.

Comfortable to sit or nap on, tatami’s moisture-absorbing function helps prevent mold. (© Pixta)

Soft zabuton floor cushions also emerged during the Edo period. Using a zabuton on tatami helped alleviate the discomfort of seiza.

In addition to manners concerning sitting style, there is also zabuton etiquette. To sit on a zabuton, you first sit in kiza position behind the cushion, with knees folded under and heels raised, and then transfer onto it by moving forward one knee at a time. When the host invites you to sit more comfortably, you respond with thanks before shifting to sitting cross-legged or with legs to one side on the zabuton.

If you are invited to a meal or other function in a tatami-floored room, it pays to bear “the three zabuton taboos” in mind. First and foremost, avoid stepping on the nicely fluffed-up cushion. Next, sit where the host indicates and do not change places without first asking whether that is all right. Lastly, in the case of a formal greeting, or when presenting a request or an apology, it is polite to do so off the zabuton from a “lower” position directly on the tatami.

The “front” of the zabuton is the side without any stitching, and the tassel in the middle indicates the cushion’s right side up. (© Pixta)

Seiza as a means of expressing respect is quite a unique cultural trait. It is a tradition that has also been passed on in the worlds of the arts and martial arts, where manners are highly valued. In competition, karuta poem card-matching game participants and shōgi or go professional players also sit in seiza mode, which has the advantage of making it easier to bend forward than when sitting cross-legged.

It has been less than a century since the wider Japanese public came to view seiza as the proper way to sit, owing to it being taught in the pre-World War II school curriculum. However, the times are changing again. Accustomed nowadays to sitting on chairs or sofas, some Japanese cannot even sit cross-legged, let alone in seiza position. At school, requiring students to sit seiza for prolonged periods is now viewed as a form of abuse. And many of the aging Shōwa era (1926–89) generation, even though raised to sit on tatami, also avoid Japanese-style rooms due to knee or lower back pain.

(Originally published in Japanese. Supervised by Shibazaki Naoto, associate professor at Gifu University, who specializes in manners education from a psychological perspective, works to guide etiquette educators, and is an instructor in Ogasawara-ryū etiquette. Illustration by Satō Tadashi. Banner photo © Jiji.)

No comments:

Post a Comment