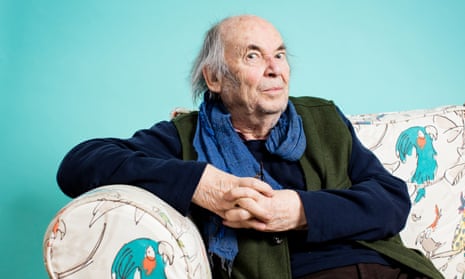

‘I couldn’t tell you where these ideas come from’ … Quentin Blake.

Photograph: David Levene

I

Quentin Blake: ‘Spend time with children? Good God, no'

Saturday 29 February 2020

The writer and illustrator Quentin Blake lives in west London in a pretty 19th-century square that has its own private gardens. Every morning, the 87-year-old takes the two-minute stroll from his flat to a nearby basement office where his assistants help to keep the Blake empire ticking over. Last year, while walking to the office, he noticed a tiny weed growing in a crack between the pavement and the bottom of the garden railings. “Each day I came past it had got a little bit bigger,” he says. “I could show you exactly where it was. In the end, it had these little white flowers. It probably only lasted three weeks, but I thought to myself: ‘Ah.’”

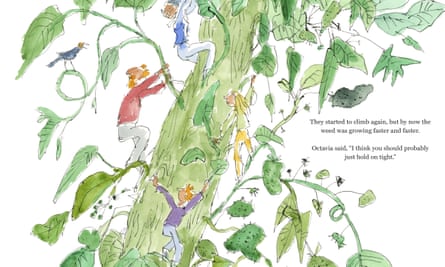

The expired plant is now immortalised in The Weed, Blake’s new illustrated children’s book set in an indeterminate future in which the world is “hard and dry, and more and more difficult to live in” and in which, without warning, a large crack opens up in the ground. We find the Meadowsweet family, plus a chatty mynah bird called Octavia, marooned at the bottom of the crack and wondering how to get out. Octavia flies to the surface and returns with a seed which she drops into a tiny crack in the rock floor. A green shoot appears, followed by leaves, branches and edible green fruit. As the weed gets taller, the family starts climbing. Eventually, it bursts above the surface and the Meadowsweets are flung on to the ground “with greenery sprouting all around them. They sat and stared around with amazement.”

I had imagined Blake would tell me, with great passion, how his book is a love letter to our ailing planet, and a cri de coeur against the political leaders dragging their feet over how to rescue it. But that is not his style. “You find the meaning as you go along,” he says, with a barely perceptible shrug. “It’s a symbolic thing – there’s the cleft in the ground and the fact that we’re in it … It’s not spelt out.” Blake isn’t in the business of preaching, “but, I mean, if people draw some of [this book] into their bloodstream, it could alter the way they see things”.

The Weed will be published alongside two earlier titles – 2014’s The Five of Us, in which children with varying disabilities go on a day trip, and 2018’s Pens Ink & Places, a hotchpotch of illustrated series, murals and one-off commissions – which will both be available in paperback for the first time. Blake is also keen to tell me about the QB Papers, a series of books that he is self-publishing. “It’s an excuse for nonsensical drawings, really,” he says. “An act of pure self-indulgence. We’re bringing out five [volumes] every three months. There’s The Mouse on a Tricycle, which is really a tiny silhouette of a mouse – the focus is on people’s reaction to it. And there’s another one called Chance Encounters, which has two tightropes over a mountain pass – someone’s walking one way with his mother on his back, and the other is walking the other way with some other strange family situation. I couldn’t tell you where these ideas come from.”

Scrawly, often joyful and entirely unmistakable, Blake’s drawings have given some of children’s literature’s most cherished characters their visual identities, in books from Roald Dahl’s The BFG, Matilda, Fantastic Mr Fox and The Twits to David Walliams’s Mr Stink and The Boy in the Dress. Britain’s first children’s laureate from 1999 to 2001, Blake has also illustrated poetry collections by Michael Rosen and the stories of his lifelong friend John Yeoman, with whom he shares a flat (Blake has previously said he is not gay), as well as creating his own characters including Mister Magnolia and Mrs Armitage. In the past 15 or so years, his work has moved into public spaces: he has drawn murals for hospitals all over London as well as in Sheffield and at a maternity unit in Angers, France (the French government made him a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres in 2004).

Blake, left, with Roald Dahl. Illustration courtesy of 2020 Roald Dahl Story Company Ltd/Quentin Blake

We are sitting on a sofa in Blake’s office, the fabric of which is printed with his illustrations (you can also get Blake wallpaper, mugs, fridge magnets and tea towels). He is small, softly spoken with twinkly eyes and sticky-out hair: I’m not the first to observe that he looks a lot like one of his drawings. He is not sure how many books he has illustrated – “I haven’t counted them recently” – but reckons it’s more than 400. Despite being semi-retired, he is still incredibly prolific. He’s mostly given up doing public appearances and has scaled back the commissions. “Which means I can draw anything, you see,” he says, delightedly. “I draw every day. I draw in bed and when I’m sitting like this on the sofa.”

His studio is in his flat around the corner, and he has another one in his other house in Hastings. “I spent 40 years working standing up at a plan chest with a light box on it, and eventually my doctor said: ‘No wonder your feet hurt. You’d better sit down.’ Sitting down still feels rather odd, though lying down is perfectly all right. Do you know Michael Morpurgo? He writes everything in bed.”

Blake is, he says, a fast worker. He once described his style as “deceptively slapdash”, though “if you know anything about it, [you know] it isn’t slapdash,” he adds. “I had a very nice student who once said ‘You’re like Fred Astaire, you make it look easy.’” I ask whether he looks for people’s visual quirks and stores them for future reference. “I think I must do, but I’m not really conscious of it,” he replies. He will act out certain positions himself while drawing people, and has been told that he pulls faces, too. “I do a lot of rough [drawings] for commissions. Sometimes I go back to the roughs, and there might be someone standing looking at someone else, and they’ve got an expression on their face that I didn’t know I’d put there. You can’t always get it again. You don’t think: ‘He should be looking suspicious.’ You just go into his situation, and, well, you don’t know quite how you do it.”

He struggles to draw cars and buildings but birds have been a recurring motif, from the magpies in The Twits and the mynah bird in The Weed, to his illustrated version of Aristophanes’ The Birds. “I don’t know why,” says Blake. “Perhaps it’s partly because they’ve got two legs like us.” He asks his assistant, Nikki, to hand me a copy of his 2005 book, The Life of Birds, in which there are birds in spectacles walking in the park, birds as adolescents standing moodily with their hands deep in their pockets, and a bird sitting at a desk writing letters. A recent commission, he tells me, involved a series of drawings about whisky, and he was asked to bring in characters from Shakespeare’s Macbeth – “and they all ended up as birds. It’s what came naturally.”

Although he turns down a lot of work, he still enjoys the challenge of drawing to order. Collaborations with authors have sustained much of his career. “Reading is the only thing I’ve got a qualification for,” he chuckles (he studied English at Cambridge). “I like drawing for myself but all those books, they’re so different in character … People often ask me where I get my ideas from and I say: ‘I get them from writers.’”

Born in 1932 and raised in Sidcup, Kent, Blake doesn’t recall seeing many illustrated children’s books as a child. In his early teens he became aware of the 19th-century French caricaturist Honoré Daumier. “He was fascinating to me because he was an artist of major stature, but in newspapers.” He recalls going to a shop in Bromley with his mother and paying two guineas for a book on Daumier. “My mother said: ‘Are you sure you want to spend all that money on a book?’ I was and I did. I still have it.”

Blake sent drawings to Punch magazine in his teens and, to his surprise, it paid him for them. He later found a mentor in the painter and illustrator Brian Robb, whom he tracked down at Chelsea School of Art with a view to studying with him. “He told me: ‘Don’t join my illustration class.’ I think he thought I’d done enough on my own. So instead I took in my drawings and he gave me a tutorial. He looked after me very well, and when he died he left me the contents of his studio. Extraordinary.”

After university, Blake did a teaching diploma. The plan was to teach English, which he did part-time for a while, but he went on to teach illustration at the Royal College of Art. After university, he knew he wanted to draw full-time but, he says, “received wisdom was that you couldn’t make a living from it”. He had the last laugh; when he finally gave up teaching to concentrate on drawing “my income increased dramatically”.

Blake is currently working on drawings to accompany a series of poems by Michael Rosen called On the Move, about migration. “It’s a children’s book but anyone could read it. It’s about members of his family, many of whom were refugees.” He didn’t want to try to draw Rosen’s family, as that would have felt intrusive. “So what I’ve done is landscape pictures of people migrating. In one I’ve got a line of them going up a hill with their bags, and there’s another one with a bombed building in it. They’re not exactly illustrations, they’re things that might have happened to those people. But they’re generalised.”

The hardest commission he ever had was Rosen’s Sad Book in 2004. It was about the author’s grief after the death of his 18-year-old son Eddie from meningitis. “I’d come across Eddie in earlier poems that Michael had written about him, so I’d drawn him as a small boy,” explains Blake. “I was very relieved that I’d never met him. It made it easier for me.” The first page had an illustration of Rosen with a smile on his face and big, wide eyes. “This is me being sad,” it says. “Maybe you think I’m being happy in this picture. Really I’m sad but pretending I’m being happy.” Usually, Blake will do two or three versions of an illustration and pick the best, but this was different. “I did it about 14 times,” he says.

Blake rarely deals directly with authors when illustrating their books, although he would talk to Dahl from time to time – “We would have a discussion about what the BFG was going to wear, and that kind of thing.” Is it true that Dahl sent Blake a pair of sandals in the post and said he’d like the BFG to be wearing them? “Yes, that’s absolutely true,” he confirms, though he adds that most authors don’t do that. Once, when Rosen was asked about his working relationship with Blake, he replied, “I give it to him and he does it.” Blake tells me this approvingly. He doesn’t like to think too hard about where his ideas come from or what they mean. He just gets on with it.

Nikki tells me it’s time for the last question so I ask Blake, who has never had a family of his own, if he ever seeks out the company of children to get a sense of what they like and don’t like. He looks slightly appalled at this. “Good God, no,” he exclaims. “Oh no. I get on with them perfectly well but spend time with them? No, no, no. There’s no need, you see. I just make it all up.”

THE GUARDIAN

No comments:

Post a Comment