Tuesday, October 31, 2023

Christian Weiss / Women

Monday, October 30, 2023

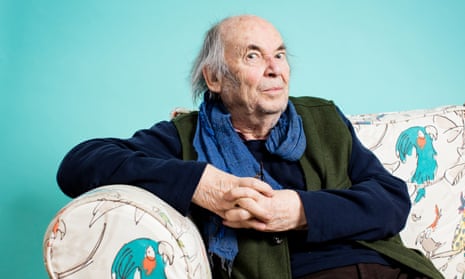

Quentin Blake / ‘Spend time with children? Good God, no'

‘I couldn’t tell you where these ideas come from’ … Quentin Blake.

Photograph: David Levene

I

Quentin Blake: ‘Spend time with children? Good God, no'

Saturday 29 February 2020

The writer and illustrator Quentin Blake lives in west London in a pretty 19th-century square that has its own private gardens. Every morning, the 87-year-old takes the two-minute stroll from his flat to a nearby basement office where his assistants help to keep the Blake empire ticking over. Last year, while walking to the office, he noticed a tiny weed growing in a crack between the pavement and the bottom of the garden railings. “Each day I came past it had got a little bit bigger,” he says. “I could show you exactly where it was. In the end, it had these little white flowers. It probably only lasted three weeks, but I thought to myself: ‘Ah.’”

‘An extraordinary ethereal force’ / Readers react to the work of Jon Fosse

|

| Jon Fosse |

‘An extraordinary ethereal force’: readers react to the work of Jon Fosse

The author finally achieved global recognition with his Nobel prize in literature, but he has been winning fans with his mesmerising prose and elemental plays for years

Jem Bartholomew

Friday 6 October 2023

When Ben Willows, a 23-year-old actor in London, was working a shift at his day job in Waterstones last September, he read the blurb of Jon Fosse’s The Other Name.

It was so striking that Willows then spent his whole afternoon break – in the cramped staff room with uncomfortable chairs and glaring fluorescent lights – devouring it. “I was absolutely transported,” he says.

The book is the first in the Septology series by the Norwegian author who on Thursday was awarded the Nobel literature prize.

“He manages to say these absolute truths and philosophies in really subtle ways,” Willows says, “and also captures thought. I think that’s what drew me in.

“I was like, yeah, that’s how I think: I careen from one thought to another, which flows into a memory, which cuts to something from years earlier that then brings me back to now.”

On receiving the Nobel award, Fosse said he was “overwhelmed, and somewhat frightened. I see this as an award to the literature that first and foremost aims to be literature, without other considerations.”

The Guardian spoke to readers about what they enjoy about Fosse’s work and how it has affected their lives.

‘He brings hope’ … Jon Fosse. Photograph: Hakon Mosvold Larsen

‘Reading his plays is like breathing in a new way’

Linda Zachrison, artistic director at Göteborgs Stadsteater, loves how Fosse is “a magician of writing what’s not said”.

“He has his own language,” Zachrison says. “When you read his plays, it’s like breathing in a new way.” In 1999, Zachrison helped bring a theatre production of Fosse’s to Stockholm’s Stadsteater.

Zachrison, 50, says plays like Someone Is Going to Come and The Name have taught her to see and approach the world in new ways. “I remember being very moved and touched, and feeling empathy for all the people that he portrayed – and also feeling empathy for the world around me … and how we’re all struggling.”

Zachrison is drawn to how Fosse’s work explores “how hard it can be just to communicate with each other,” and how language can become “an obstacle instead of a tool for understanding”.

“He’s very existential, in a way. He shows the fragility of being here,” Zachrison says, and the complexities of “how thin the line is between enjoyment or love; irritation or attraction; a wish to reach out or neglect. It’s a simpleness in his writing that opens up an extreme complexity.”

‘Even now, I get a slight shiver’

Fosse’s books in the UK are printed by London-based independent publisher Fitzcarraldo Editions, which has now won three of the past five Nobel literature prizes, with Annie Ernaux (2022) and Olga Tokarczuk (2018).

John Stout, a 69-year-old retired computer science teacher in Greater Manchester, discovered Fosse by chance after taking out a Fitzcarraldo subscription.

He received a copy of Aliss at the Fire, about a woman, Signe, in her old house by a fjord who sees a vision of herself 20 years ago – when her husband failed to return from the water on his rowboat.

“Even now,” Stout says, “I get a slight shiver” thinking about that night on the water and the “sense of impending doom”.

For Stout, it brought up memories of sailing with his father in Scotland as a boy; they sometimes sailed to the Isle of Man, and the children would have to stay quiet during the BBC shipping forecast. “She’s looking back and you get this feeling of these other generations who are there in the house, and are in her thoughts all the time.”

‘He has a deep empathy’

Camilla Bauer, a 51-year-old translator and writer in Stockholm, says that Fosse’s award is particularly poignant amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“He has a deep empathy, he can go down and really analyse where things went wrong – why people become bullies or violent – but there’s always a kind empathy,” Bauer says.

“In these days of war and cynical people killing each other, I think this was very timely. He tackles dark themes, but he shows us where things go wrong and brings hope.”

Bauer first encountered Fosse around 2010, when she went to a day dedicated to his work in Stockholm. She remembers the psychological immediacy of his dramas. As in his plays, “I have been in spaces” where people try to “take away your space, where everything you say is wrong,” leading you to withdraw into yourself – which Fosse captures so well.

‘He has an extraordinary ethereal force’

Alongside novels and poetry, Fosse has written more than 30 plays and is the most-performed Norwegian playwright since Henrik Ibsen.

Chris Lee, a 59-year-old Irish playwright in London, says he is “mesmerised” by Fosse’s work. His ability to mix theatricality and poetry makes his writing “a weird combination of Harold Pinter and Seamus Heaney in a Norwegian fjord”, Lee says. With his plays, there’s a “prayer-like effect” and an “ethereal force” that stays with you.

Lee says that, being a playwright himself, there are “many moments in your life when nothing’s happening, and you feel that maybe nothing will ever happen again”. But Fosse’s writing has been “a great source of confidence” and taught him that “ploughing your own furrow is the best thing to do”.

It’s brilliant for playwrights that Fosse was been awarded the Nobel, Lee adds, so it’s “a time for celebration”.

THE GUARDIANSunday, October 29, 2023

“Bathed in an incredible sweetness of light” / A Reading of John McGahern’s “The Wine Breath”

|

| John McGahern |

1

“Bathed in an incredible sweetness of light”: A Reading of John McGahern’s “The Wine Breath”

Liliane Louvel

70 | SPRING 2018

Special Issue: Haunting in Short Fictionp. 153-166

Résumé

Les écrits de John McGahern, ancrés dans la société irlandaise rurale qui se développe à partir des années 1950, n’ont a priori rien de fantastique, rien d’une expérience de lieux fantomatiques. Cependant, une forme de hantise s’attache à certaines nouvelles, comme c'est le cas de « The Wine Breath ». Cette simple histoire d’un vieil homme qui renonce au dernier moment à effectuer la course pour laquelle il s’est rendu chez un voisin, est l’occasion de montrer comment, par la grâce d’une vision qui tout à coup fait rejaillir de sa mémoire un souvenir ancien, le vieux prêtre est hanté par son passé. À cette occasion, l’écrivain dépeint une expérience métaphysique et phénoménologique qui amène le lecteur à suivre la récurrence du souvenir revenant trouer de sa vérité mortelle « le tissu fragile de la vie quotidienne ». L’histoire est celle du désenfouissement d’un jour de l’enfance, perdu et brusquement revécu dans la blanche vision éblouissante qui rejoue la neige d’une journée particulière.

Reading John McGahern's "Love of the world" a fistful of images

|

| John McGahern |

Reading John McGahern's "Love of the world" a fistful of images

Liliane Louvel

AUTUMN 2009

THE SHORT STORIES OF JOHN MCGAHERN

Résumé

This paper focuses on McGahern's particular use of images and metaphors as a means of concentrating the energy of a short story. This double entendre of McGahern's is also part and parcel of his use of irony and paradoxes. He was a great one for humour but could also use scathing irony when he disapproved of his contemporaries. “Love of the World” bears traces of this. I will try to show that a central image condenses the whole story perhaps true to one of McGahern's only critical texts about his work: “The Image”. This fine text written years before “Love of the World” perfectly applies here. It holds under the reader's eyes a Medusa's mirror in which “the totally intolerable” is reflected. In this text he develops one of his favourite ideas, that of the link between image and imagination and how one strong image often triggers the writing of a story or a novel.

John McGahern / "Along the edges": along the edges of meaning

|

| John McGahern by Patrick Swift |

"Along the edges": along the edges of meaning

Abstract

This paper is an invitation to read John McGahern’s short story “Along the Eges” as a mimetic exploration of a hazardous ridge between separateness and togetherness. The narrator settles along the edge of perspective, denying the reader the stability of interpretation. The experience is that of radical Otherness, dark and dazzling

Plan

The two-edged (s)word of fiction; dividing to relate

Texte intégral

Saturday, October 28, 2023

Gene Wolfe / In the Company of Wolves

|

| Gene Wolfe |

In the Company of Wolves

I became involved with the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame because I believe that Chicago has an important literary legacy deserving of attention. After two induction ceremonies where we celebrated historical writers, it was time to look at the contribution of writers living and working in Chicago.

After some discussion, it was unanimous, and we moved forward to create a new award, the Fuller, to honor a lifetime contribution to Chicago literature.

Shock of the new / Jordan Peele, Mariana Enríquez and more on the horror fiction renaissance

|

| Marina Enríquez |

Shock of the new: Jordan Peele, Mariana Enríquez and more on the horror fiction renaissance

There was a time, a few decades ago, when horror fiction meant just a few names. Stephen King and Dean Koontz in the US, James Herbert and Clive Barker in the UK. It was a boom time for sales but not critical recognition: a sea of paperbacks passed beneath school desks. And then, in the mid 90s, horror largely disappeared. Writers of darkness were repackaged into more market-friendly categories – thriller, dark fantasy, or that neutering, catch-all classification: suspense.