Anuk Arudpragasam’s A Passage North is a montage of musings told through its protagonist’s cascade of stream-of-consciousness thoughts. Krishan, a young Sri Lankan man, grasps the insidiousness and enormity of the civil war that raged on for 30 years only in its aftermath, devoting himself to understanding the way the worst massacres had happened through mental timelines, trying to construct, through his act of imagination, a “kind of private shrine to the memory of all those anonymous lives” lost during the war. Arudpragasam does precisely the same through the novel, which is a eulogy for the thousands of Tamils who lost their lives during the last two years of the war; a eulogy, and not an elegy — the novel does not so much lament the dead as it commends them. The men and women killed during the war were not given dignified funerals, but Arudpragasam endeavours to offer them dignity in death by dwelling, towards the end of the novel, on the act of ritualised mourning.

Language is the means by which writers negotiate their relationship with time. Arudpragasam begins A Passage North with a riff on the idea of the present and the passage of time. He writes how we keep going through the “circular daydream of everyday life” — waking up each morning to follow the thread of habit, moving ‘unseeingly through familiar paths’, going out into the world and retreating back to our beds at night — and how it is only when the strong pulls of desire and the ache of unexpected loss interrupt the rhythms of our lives that we are surprised to find as if “we were absent while things were happening during the time that’s referred to as our life”. As it has been the case with other Sri Lankan writers like Romesh Gunesekera, writing becomes an act against the corrosiveness of time for Arudpragasam, too; it allows him to retrieve the past and take a shot at stopping, or slowing down, the passing of time. It’s no wonder then that his writing in the novel is structured around the different ways in which time passes.

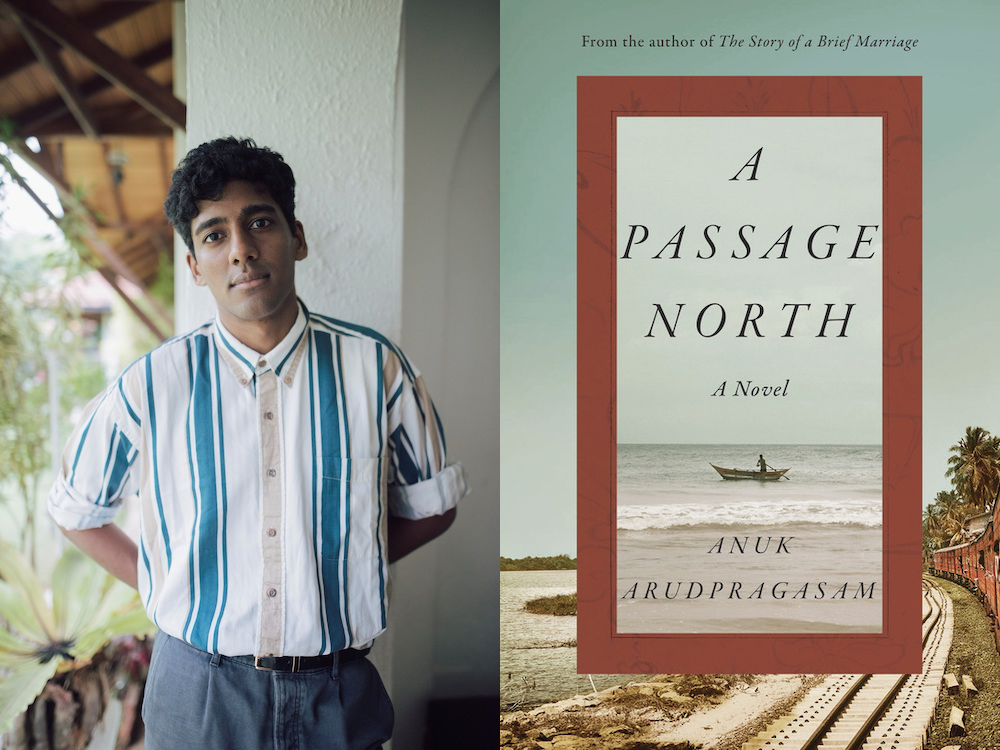

This structure in his rendering of consciousness was also evident in his spectacularly assured debut novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage (2016), which he wrote when he was pursuing PhD in philosophy at Columbia University. It unfurls over a single day and deals with the immediate, bodily experience of violence by a newly married couple who struggle to stay alive as the Sri Lankan Army closes in on them. It examined how people live and die in a time of war. His second novel, in contrast, concerns itself with indirect experiences of violence — an account of people living and dying in the aftermath of war: “the psychic repercussions of trauma or the spectatorship of violence from a distance.” At 33, Arudpragasam is precociously observant and perceptive. He has his gaze fixed at the erasures of history. Both his novels underline the need to remember in the face of collective and institutional amnesia around the war.

A Passage North, which unfolds over the weekend, explores how violence is lodged in the soul and the psyche of the survivors, their emotional wounds and scars refusing to heal with time. The novel opens with a call informing Krishan — who lives in Colombo with his grandmother, Appamma, who is gradually withdrawing from the world, and his widowed mother, a teacher — that Rani, his grandmother’s caretaker, has died. The call comes at a time when Krishan is preoccupied with the thoughts of Anjum, an activist, with whom he had a brief relationship when he was studying in Delhi, before he moved to Colombo. As Krishan takes a train journey to attend Rani’s funeral in Kilinochchi, a village in the far north, travelling through the sinewy landscape of Sri Lanka’s impoverished countryside, he traverses not just any “physical distance”, but also some “vast psychic distance inside him”. The journey makes him ponder over the paths chosen by Anjum and him, and also by the Tamil cadres, including Dharshika and Puha, who believed in the cause of a separate Tamil-speaking state and sacrificed their lives for it.

A Passage North is deeply philosophical and intensely political and layers time and space, feelings and sensations. It dwells on the cutting of ties, the act of voyaging into the unknown and the crystallisation of two contradictory possibilities of life with remarkable sensitivity. The novel’s philosophical musings unspool in long sentences; some paragraphs run into two pages, and there are no dialogues. This can be exasperating for some readers, but this also enables Arudpragasam to pull off bursts of narrative epiphanies, like a remarkable passage where he describes Krishan’s remembrance of the language and imagery of Kalidasa’s Meghaduta (The Cloud Messenger). In the poem of yearning written in Sanskrit, its unnamed main character, a yaksha, a kind of semi-divine spirit, who served the god of wealth, is exiled from Alaka, his beautiful native city in the foothills of the Himalayas, as punishment for neglecting his duties. The yaksha asks the cloud to bear a message from him to his wife, providing it with detailed set of directions to find his city and, eventually, his wife. Elsewhere, Arudpragasam crafts other passages that centre on the nucleus made of instants and incidents, demonstrating how he ruminates slowly and patiently on life in a manner that is philosophical, but also intimately tied to the texture of the everyday. While reading the novel, I kept thinking of Peter Nadas, especially his novel A Book of Memories (1986) and its microscopic analysis of the subtleties of social interactions — mundane, but somehow endowed with meaning. Arudpragasam’s daring and demanding prose and his artistic experimentation show a similar protraction, force and classicism.

During the seven-hour train journey from Colombo to Kilinochchi, Krishan looks back at the years he had spent in Delhi when the events of the northeast had filled him with shock, anger and shame as well as guilt for having been spared. He had not directly experienced the war; his father, though, had been its casualty. He had immersed himself in poring over the images of the war on the internet. He also reflects on his short but passionate relationship with Anjum, the train to Mumbai they had taken and the circumstances in which they had to part ways — the bliss of union and the desperation of being parted, the “vanishing space” between desire and satisfaction and the disappointment that the attainment of desire brings. While describing Krishan’s love and yearning for Anjum, Arudpragasam is particularly eloquent. Here is a sampler: “Falling in love…was not so much an emotional or psychological condition as an epistemological condition, a condition in which two people held hands and watched in amazement as the world around them was slowly unveiled, as the falsities of ordinary life began to thin and dissolve before their eyes, the furrowed eyebrows and clenched jaws, the bright colours and loud noises, the surface excitements and disturbances all dropping away so that what remained — time stripped bare — was the only way the world could truly be apprehended, so that even if this condition did not last, even if it was lost, as eventually as it is always lost, to habit or circumstance or simply the slow, sad passage of the years, the knowledge it has imparted remains, the knowledge that the world we ordinarily partake in is somehow not quite real, that time does not need to pass the way we usually experience it passing, that somehow it is possible to live and breathe and move in a single moment, that a single moment could not be a bead on an abacus of finite length but an ocean that can be entered into, whose distant shores can never be reached.” He also excels at delineating the dynamics of the relationship between his grandmother and her carer Rani, leavening the inherent sadness of their condition with occasional lightness of touch.

Desire and yearning, longing and loss are some of the themes coursing through the novel’s vein. Rani had lost her two sons when shrapnel shells had hit them during the last years of the war. The sense of grief and loss had stayed with her during the remaining years of her life, turning her into a shadow of her former self, a ghost-like figure: Her “vividly painful longing contained both the particularity of desire and the direction lessness of yearning.” Krishan’s presence at the scene of desolation seemed to have been preordained, with certain forces having led him to leave the life he had created for himself in India, to come to the place he had never actually lived in and which had hardly figured in his life while he was growing up: “The specific path a life took was often decided in ways that were easy to discern, it was true, in the situation into which one was born, one’s race and gender and caste, in all the desires, aspirations and narratives that came thereafter to identify with, but people also carried deeper, more clandestine trajectories inside their bodies; their origins often unknown or accidental, their modes of separation invisible to the eye, trajectories which were sometimes strong enough to push people in certain directions despite everything that took place on the surface of their lives. It was such a trajectory, set in motion by the things that they had seen, that had led so many young men and women to join the separatist movements decades ago, it was such a trajectory that had led Rani and so many people like her to their accidental or intentional deaths in the years after the war, and it was such a trajectory, Krishan now felt, that had led him too, in his own quiet and unremarkable way, to this cremation ground at the end of the world.”

Just like Poosal, an impoverished man from Ninravur village in Tamil poem Periya Puranam, who had meticulously constructed an exquisite temple for Lord Siva all in his mind, Krishan, after his return to the island, had abandoned the world around him to cultivate “a kind of alternative space in his mind”, a space he had imagined into existence; Having joined a small NGO in Jaffna, he had dedicated himself to the reconstruction work in the months and years after the war’s end: “The last shells had long since fallen, the last bodies been long since cleared, but the mood and texture of this violence suffused the places he went to such an extent that even his way of walking changed while he was northeast, his gait acquiring the same quiet reverence of someone moving in a cemetery or cremation ground.” While working in the northeast after his return from Delhi, Krishan had connected with the land and people in a substantial and meaningful way, but also realised how time “never seemed to be heading anywhere but was always circling, returning, and repeating, bringing the self back to itself. After absorbing the pain and grief, he had envisioned participating in some kind of dramatic change, but had come to the conclusion, as months bled into years, that “these visions would never be achieved, that some forms of violence could penetrate so deeply into psyche that there simply was no question of fully recovering.”

The impossibility of closure and the inexorable march of time are summed up by the third-person, who is the alter ego of the author, thus: “We experience, while still young, our most thoroughly felt desires as a kind of horizon, see life as divided into what lies on this side of that horizon and what lies on the other, as if we only had to reach that horizon and fall into it in order for everything to change, in order to once and for all transcend the world as we have known it, though in the end this transcendence never actually comes, of course, a fact one began to appreciate only as one got older, when one realized there was always more life on the other side of desire’s completion, that there was always waking up, working, eating, and sleeping, the slow passing of time that never ends, when one realized that one can never truly touch the horizon because life always goes on, because each moment bleeds into the next and whatever one considered the horizon of one’s life turns out always to be yet another piece of earth.”

No comments:

Post a Comment