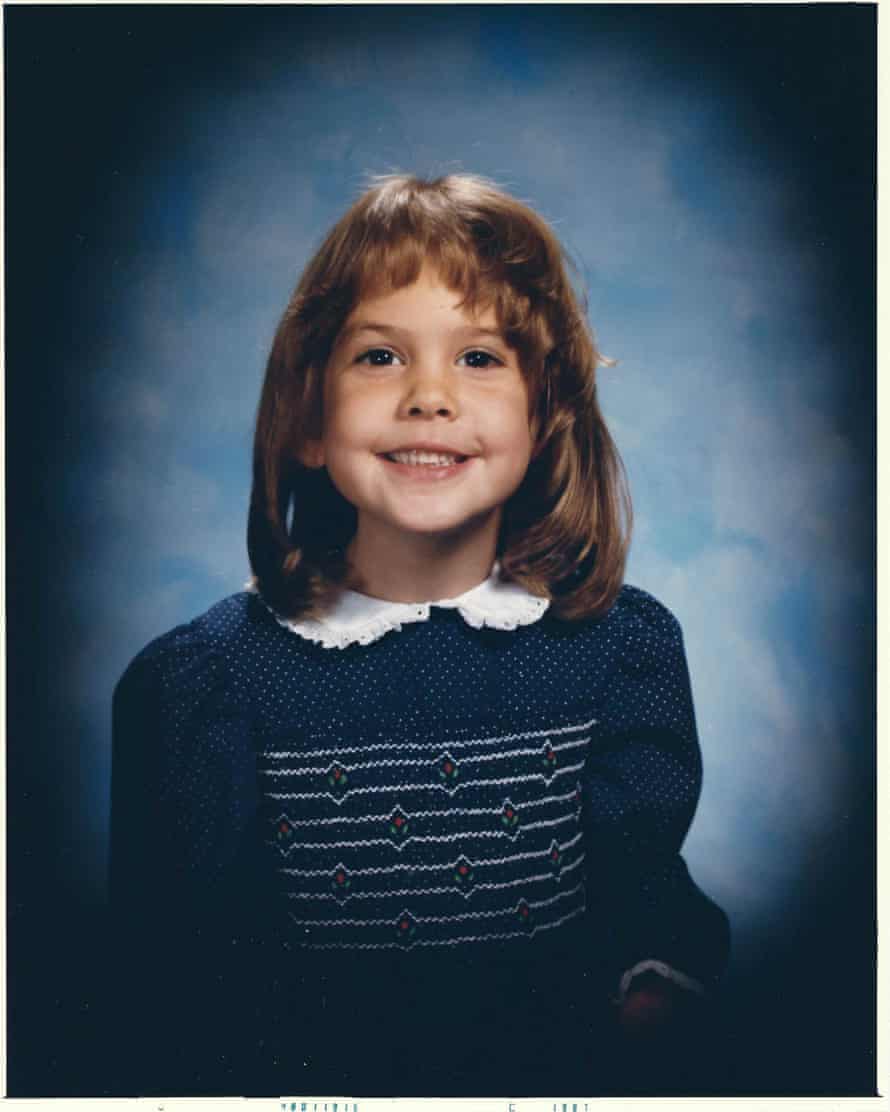

The poet and author, best known for her long poem Rape Joke, talks about her extraordinary memoir, Priestdaddy, and growing up in the midwest

Kate Kellaway

Sunday 30 April 2017

I

Her father – the Priestdaddy of the title – was on a nuclear submarine off the coast of Norway during the cold war and watching The Exorcist (he saw the film more than 70 times in 88 days) when he underwent an unlikely conversion to Catholicism and became, having found a loophole in sacerdotal law, a married priest. Lockwood’s mother (“the most quotable woman alive”) is unusual too, although less flamboyantly strange. Had her mother been able to join us, Lockwood ruminates, she would certainly have ordered iced tea and certainly immediately sent it back, protesting it tasted like “sewage”. “That would happen because it has happened at every single breakfast, lunch and/or dinner I’ve had out with my mother.” This certainty about oddball details is part of the Lockwood – Tricia to her friends – magic, although she wonders aloud, more than once, where her authority comes from. With no college education, she has risen out of slush piles and triumphed. Her poems have appeared in the New Yorker and the London Review of Books and she has had rave write-ups in the New York Times.

This is her first visit to London and, before setting out, she consulted her Twitter followers (600,000 plus) about suitable books to read in Europe. Dubbed “the poet laureate of Twitter”, Lockwood has delighted fans with the invention of the poetic sext – surreal parodies of sexual text messages (“I am a living male turtleneck. You are an art teacher in winter. You put your whole head through me”). But she is even more famous for her long, serious poem Rape Joke (which went viral, and of which more later). Thanks to her Twitter following, she comes to London complete with an eclectic travelling library: Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, Colin MacInnes’s Absolute Beginners and Party Going by Henry Green. More significantly, her Twitter audience came, incredibly, to her rescue, four years ago, after she and her husband, Jason Kendall, received some bad news.

Jason was discovered to have advanced cataracts and needed a costly operation to save his sight. Lockwood’s Twitter followers, between them, donated the necessary $10,000. To economise, Tricia and Jason moved back into the Lockwood family home. The decision to write the memoir (“I’m not a novelist”) was an attempt to stay sane and make money. She wondered whether to call the book Lapsed but felt too much of a Catholic to do it. “Faith and my father taught me the same lesson,” she writes, “to live in the mystery, even to love it.” But what does this mean in practice? “It is a Catholic idea to live between knowing and not knowing. There is this person who somehow produced you, yet you don’t know him and he doesn’t seem to know you. You accept facts about each other but there are deep wells of mystery. Mystery always seems more pronounced with your parents, doesn’t it?” And she gives her at once knowing and uncomprehending squeal of laughter.

Her father will never read her book because it is “not theological and has no submarines in it” – no joke, apparently – “and that is very freeing”.

Writing has always been her haven, a “place I could go where he was not looking”. So why did her father convert – The Exorcist aside?

“My father is a contrarian and contrarianism the arrow that would point him in a direction opposite to all he had known. Conversion is a form of revelation. It’s not something you can argue with thousands of feet under the sea. But he went to extremes – wearing a dress, saying the Latin mass.”

Not that the dress is reliable: Greg Lockwood, his diocese now in Kansas City, wanders about semi-nude at home and sits “with his thighs spread so wide it seemed like there might be a gateway to another dimension between them”. He has always been “fascinated by cement mixers whose job it was perpetually to stir”. His extravagant guitar-purchasing habit robbed Patricia of a college education (“For a long time, I really, really minded”). He brandishes guns with unholy spontaneity. His “two antecedents in English literature are Toad of Toad Hall and Uncle Matthew from Nancy Mitford’s books”. He might come across as a cartoon but close friends tell her: “Tricia, you underplayed him by 40%.”

Patricia met Jason (son of missionaries) in 2002 through an online poetry message board. They married at 21. The first time Jason met his future father-in-law, he found him sitting “practically nude, and surrounded with gun parts like a deranged warlord”. At the fake Mexican restaurant where the family went for a first get-together feast, her father “packed a gun into his pants…What? Are you going to shoot him in a Mexican restaurant?”

Did you try and explain him to Jason? “No. I was like: let this tsunami close over your head and, eventually, you’ll surface at the top and take a deep breath – that is the only way you can deal with my family.”

It seems amazing she and Jason are still married, I say. She peals with laughter. “Marriages are very different when you grow up together.” She concedes that 2001-2 was a hazardous era for internet romance, not least because you could not see the person and “might hook up with an ogre on the internet’s bodiless plain”. Jason, a journalist, designer and editor, emerges not as ogre but as unruffled saint.

As with her writing, she likens him to a haven: “He is an oasis of a person.” He is also the man who successfully pelted the publishing world with submissions on her behalf.

They now live in a basement flat in Savannah, Georgia, “one of the loveliest cities in America because it didn’t get burnt during the civil war”. Slightly overpopulated with “statues of confederate generals”, it boasts “huge spreading oaks with Spanish moss dangling down”.

Lockwood works in bed, “prone – the best way to think is not to move at all. I have to have total silence. And I can’t move because I’m covered with three cats. One is a secret my landlord does not know about, she has to hide whenever he comes over.”

She started writing poems at seven. Her first poem was “a terrible haiku about a diamond drop trembling on a leaf”. Its last line was, “Beauty its own life”. This sounded sophisticated and was praised but she had “this nagging feeling it didn’t mean anything”. She suggests her career might have grown out of appreciating the perils of eloping with words. At least, when you read Rape Joke (2013), the sense is not in doubt. It describes her traumatic experience as a teenager, raped by one of her father’s students, seven years her senior. The feedback to this poem was astounding. She felt supported and exposed.

“Young women were sending me their stories and, at the same time, there was this flash of worldwide exposure. I felt I was carrying, as my father does, a confessional weight.” There was reaction at home too: “I came downstairs and Mum was sitting in total darkness with her laptop open, a haunted expression on her face. She said, ‘I have just read Rape Joke.’ I said: ‘Mum, you sound like you are being murdered.’ But then she was very sweet, she came over and embraced me.” Her father knows about it and has not read the poem.

Has writing success changed Lockwood’s life? “From early on, I had the idea that this is how it would be, that people would know who I was. It was an insane wave of self-belief – not earned.”

She prefers not to be watched, “yet I’m also an enormous show-off. I’m a clown who needs to sit and think about life, death, the churchyard and grave.” Her father maintains she is like him. “We both want to stand up in a pulpit and have a shared concern with important, abstract questions (even if our language is different).” She suggests that “every family is a cult, mine especially” but feels, “I exist alone”. And she does – a charming, clever, funny one-off. But when she wonders where her authority comes from, I can’t help thinking Priestdaddy must be part of the answer.

No comments:

Post a Comment