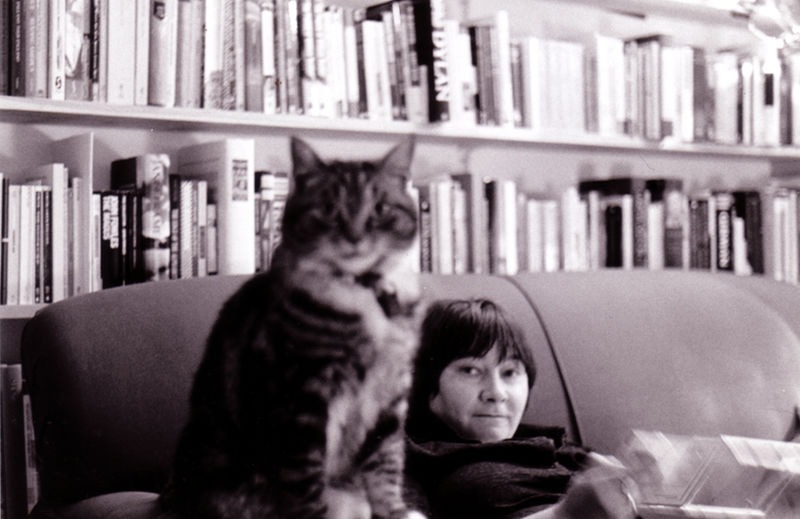

Ali Smith, with Leo, in Cambridge, 2003.

Ali Smith

THE ART OF FICTION

No. 167

Interviewed by Adam Begley

The Paris Review No. 236

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a routine when you write?

SMITH

Usually I get up around nine, I stay up quite late, till one or two in the morning, and work till quite late. But for How to be both I would get up at seven and use the first two hours to skim read—I was writing the book very fast and knew far too little about the Renaissance. So in the hours I’d usually still be asleep and dreaming, I read books about, say, the formation of building materials in Ferrara in the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries. At one point, for instance, the local river path was diverted, which made for a whole new possible clay mix, a new kind of brick. The stuff of dreams. But that was unusual for me. Normally I don’t do research at all.

If I’m not writing to meet a deadline, I tend to spend the mornings doing admin—emails and stuff—and then start writing about two or three in the afternoon and work through until about eight or nine. I’m quite lazy, though. I spend lots of time staring into space and wandering around the room, picking things up, opening books, putting them down again.

INTERVIEWER

Did you know early on that you would write?

SMITH

I knew early on I would do something. I was proficient at lots of things—I was a proficient, happy, versatile child.

INTERVIEWER

Were you a voracious reader then?

SMITH

I read all the time—but was I voracious? I loved films. And I loved theater. Not that there was much theater in Inverness. In my childhood, all the local theaters—except one called the Little Theatre, at the bus station, which played amateur dramatics—had closed down with the advent of film. When I was about fourteen and they opened a fantastic new theater, I spent a lot of time there, saw practically everything that was on, and every film—Sunday nights they showed films from all over the world. The first film they showed was Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, and in my teens I saw films by Varda, Truffaut, Rivette, Tati, films from France, Germany, The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum, amazing films by Margarethe von Trotta.

But reading. My mum and dad knew and believed that books had an especial value, but they didn’t have time for reading, and we didn’t have that many books in the house. I don’t think people did at that point—they went to the library. The difference between my early teens and late teens is the number of books that started to fill my room after a secondhand bookshop in Inverness opened, Leakey’s, and I spent all my Saturday money there. Then the local bookshop—there was only one—opened their basement up and started stocking new paperbacks, Penguins and Picadors, and I sort of began to live there. I was in there all the time.

INTERVIEWER

You went to university at Aberdeen, to study English.

SMITH

I had to fight for that. My parents wanted me to be a lawyer, and I wanted to study English. Partly because I’m lazy and knew I would enjoy it. And because I could do it without going against my own nature.

INTERVIEWER

Were you already writing at this point?

SMITH

I’d been writing plays while I was at school—

INTERVIEWER

High school?

SMITH

Primary school, too. At Aberdeen, I became a poet, a really terrible poet. Then I wrote a couple of short stories. One of them got published in an anthology called New Writing Scotland, and the other in a book of travel pieces put together by the Sunday Times. It was a competition. Beryl Bainbridge was one of the judges. The editor wrote a note in pencil at the bottom of his acceptance letter saying, Just to let you know, Beryl Bainbridge particularly liked this story. Oh, I was chuffed! I was twenty.

INTERVIEWER

And then you went to Cambridge to do a Ph.D.

SMITH

I came to Cambridge and started to write plays again. Eventually we took three or four plays to the Fringe festival in Edinburgh. By we, I mean Sarah, my partner, and I—I met her because she was a director. I wrote several plays which she then directed.

At Cambridge, I wrote a thesis, about Joyce, Stevens, and Williams—about the years 1922 and ’23, in which Ulysses, Harmonium, and Spring and All came out. I had a theory about the importance of the “real” and the use of the real, authenticity, or the “actual.” I’d no idea about philosophies of reality—it was an instinctual reading. When I handed it in and it went to examination, I was referred, which means that they want you to change what they want you to change. What they wanted me to change was the first chapter, an overview of the roots and fruitfulness of modernism. It was highly unfashionable, right then, to suggest that modernism was a roaring energy rather than a time of broken, ghosted fragmentation. Anyway, it was referred on that first chapter, and at Cambridge, if you don’t resubmit your thesis within ten years, you get a letter telling you you’ve failed. But the chapter they’d wanted me to change had got me two academic jobs. It got me a lecturing position at Goldsmiths, and it got me a lectureship at the University of Strathclyde, the job I took. I just thought it was daft to rewrite something that had got me two positions. So I didn’t resubmit. So I’m on the failure list. I quite like being a failure.

INTERVIEWER

What was the teaching job like?

SMITH

It was an interesting eighteen months. On the very first day of my very first teaching term, the new teaching staff all met in this plush university auditorium I never saw again, where we were instructed by personnel that we were to call our students “clients.” I spent the year and a half working like crazy, incredibly hard, a lot of the time teaching things I knew nothing about. I taught Chaucer, whom I hadn’t really read, hadn’t more than skimmed, till then. I taught the Brontës, whom I had read, once, five years ago, and so on, plus I was always conscious that I wasn’t necessarily giving my “clients” what they wanted. I wasn’t giving them any answers—what that green light at the end of the dock “means” in Gatsby, what the lighthouse “means” in To the Lighthouse.

INTERVIEWER

And then you fell ill.

SMITH

My mother died in January 1990, not long before I handed in my thesis. That August I went to work at Strathclyde, on the back of grief, thinking that’s what we do—we roll on, we deal with it, we keep going. Then, during my second spring at Strathclyde, I was crossing a road, and it felt like something hit me in the head. It felt like I’d been hit from the back with a baseball bat—after which I took the hit, as it were, and went into a kind of physical breakdown, in which it became almost impossible, for months, to move across a room, to cross a road, to walk up a street.

INTERVIEWER

Your first book, Free Love and Other Stories, came out in 1995—was it somehow a result of your illness?

SMITH

It actually sidelined the illness. It was the thing I could do while I was getting better. It was very hard to use my arms—my arms were very sore, my whole body was sore—and trying to write longhand really hurt. But I found I could write short pieces which would come together as short stories, and that’s what I did.

INTERVIEWER

The first story, the title story, “Free love”—did you put that at the beginning as a kind of declaration?

SMITH

The publisher didn’t want me to, I remember, and didn’t want to call the book Free Love. But I really liked the opening line. “The first time I ever made love with anyone it was with a prostitute in Amsterdam.” I remember thinking that first story was a decider—it would tell you everything, if you paid it proper attention, from its first line on. I thought, If you open the sensitivities of the reader that early, then the sensitivities of the reader are open for the rest of the book.

INTERVIEWER

Do you look back on that first collection with pleasure?

SMITH

I don’t look back on any of them, really. Ten years after I wrote Free Love, I read one of the stories out loud, and I thought, Well, that’s all right. You get a thing at the back of your neck that tells you it works, that the thing’s held together properly. But I can’t read them.

INTERVIEWER

Did you have trouble finding a publisher for it?

SMITH

Well, trouble is relative. When I was at Aberdeen, when I was twenty-one, and I met Bernard MacLaverty, he at one point said to me, Send your poems to this agent I know. And I sent her a bunch of poems. Her name then was Xandra Hardie—she’s changed her name since, she’s my dear friend Xandra Bingley—and she wrote back and said, This is all very well, but do you also write prose? I put the letter aside, but years later when I actually did write some prose, I sent her about nine stories, and she wrote back saying, Write a few more of these, and I’ll start sending them out for you. She sent them out to five, six people. She got back a bunch of rejections, one of which, interestingly, said, These aren’t really what we publish. They’re too “lifestyle.”

INTERVIEWER

Lifestyle?

SMITH

I think it was a way, in 1994, of saying gay. But Virago liked them and took them on. And they said, If you write a novel, we’d like to see it, and we’ll probably take it. And I said, Okay, I’m writing one—and then started to write one.

INTERVIEWER

That was Like, which feels like an overture—all of Ali Smith crammed in there, the scrambled chronology, the precocious preadolescent girl, unrequited love, a highly significant painting, a literary academic, puns galore, a fascination with simultaneity, and so on. Where does Like come from?

SMITH

I presume from the split between England and Scotland, a split that I experienced, going up and down the country in the awful split Thatcher era. It’s a very split book.

INTERVIEWER

Can we talk about ghosts? In Like, you refer to Scotland—“the bleak frozen north”—as “ghost-ridden.” Then you’ve got ghosts in Hotel World and Artful and How to be both.

SMITH

Well, there are different Scotlands. By “the bleak frozen north,” I mean the high, treeless, mountainous moorscape between the Lowlands and the Highlands—the Slochd, the Pass of Drumochter. But the Highlands, particularly the Highlands, are full of ghost stories. No wonder—look at history. A people was obliterated, in the aftermath of the Jacobite rebellions and then the Clearances, and that people’s language was obliterated, too. A language declared illegal. So there’s always the ghost sense under an English word of the Gaelic word.

My father, an Englishman from the North of England, was a serious ghost-story teller. I remember two of his ghost stories—they weren’t stories to him, he told them like real-life anecdotes. They’d happened. When he was a child, he said, he was in bed with his brother, he was seven or eight, and a child appeared in the doorway—it was a child missing at the time, later found murdered, and he appeared to my father, the child. And then, in his war years, he said, he was driving back from somewhere or other and he saw a man he slightly knew standing in the middle of the road with his big tall motorcycle boots on. The truck drove past, he waved, but the man didn’t see him. Then when he got to wherever he was going and said he’d seen this man, they told him that the man he’d seen had died twenty-four hours before, crashed his bike and died on the road.

INTERVIEWER

Sudden, mysterious death and an intensity of mourning feature in Artful and in How to be both. Is this imaginative sympathy on your part?

SMITH

Particularly with these last couple of books you just mentioned, it was a time of steady loss for me, for us. My dad died in 2009. My partner’s mother died two years after, and then, just over a year later, her father died. So I now think of those books as an examination of grief, partly for her. Because the mortalities we live mundanely, the shock of them—we aren’t allowed to articulate. It’s very hard to articulate grief in a world which doesn’t want you to, which tells you to push on, to continue.

INTERVIEWER

I got the feeling with Artful that you were imagining your own death and how that would be mourned.

SMITH

No. Simpler than that. When you have love in the equation, you also have death in the equation. The love story is always about the threat and the promise of loss. Artful came from an instinctual place. The last couple of books have been fast for me, but Artful was written very fast.

INTERVIEWER

From a reader’s point of view, it feels artful, a layering of love story, ghost story, and criticism—fact blended with fiction.

SMITH

I was coming up to fifty years old when an Oxford college wrote to me and asked, Do you want to do this series of lectures, the Weidenfeld Lectures? And I was like, Oxford! Lectures! Well, will I? Since I’m nearly fifty, and surely by now I can own whatever authority I’m supposed to have, surely I know something useful by now, surely I can move into my more mature self, have some wisdom by virtue of experience, et cetera. So I said yes. But the dates for delivering these lectures got nearer and nearer, and I put it off and put it off and put it off, and then the first deadline was looming, really looming, the first one was about a fortnight away and I hadn’t written any of them. What I had been doing instead, because I’d become interested in the word artful, was reading Dickens’s Oliver Twist, a book which gave copiously as I was working on Artful.

But I couldn’t be that authority you’re supposed to be when you stand up in front of people and go, This is the way things are. I couldn’t do it. It wouldn’t have been true, either to me or to whatever “authority” I actually do have. I found that out in the writing and the giving of the lectures.

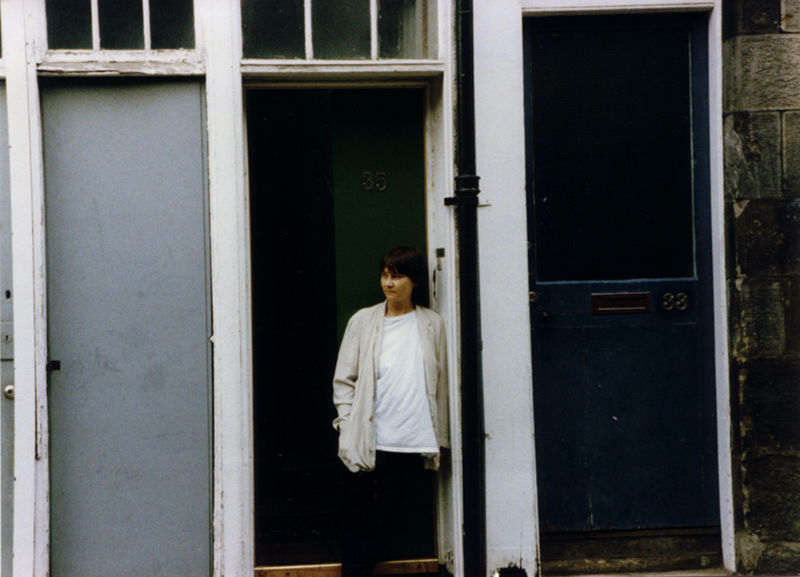

Ali Smith in Edinburgh, 1992.

Ali Smith in Edinburgh, 1992.

INTERVIEWER

Is Artful a novel?

SMITH

I think it probably is. But I’m not going to take umbrage if people say it isn’t.

INTERVIEWER

A number of your novels—I’m thinking especially of Hotel World, The Accidental, and There but for the—seem to germinate from a shocking or troubling incident. The dumbwaiter accident, Amber’s unlooked-for arrival, Miles’s decision to occupy the guest bedroom—each one a catalyst.

SMITH

Probably filmic—a visual device which allows you to build a spatial happening around it, which becomes the novel.

INTERVIEWER

And is that how the composition works? You imagine consequences?

SMITH

With Hotel World, I didn’t even know there was an incident until I sat down to write it. I had promised the publisher a novel about a hotel—the people who can afford to stay, the people who work, and the people who can’t afford even to enter. But when I sat down to write, what happened was something else altogether, and that was the dumbwaiter incident—at first, I thought I was perhaps writing something for a different book altogether, then I saw how central to the structure it was—where a girl who’s working there climbs into a dumbwaiter for a bet and the thing plummets to the ground. I was, ultimately, immensely grateful that the incident just appeared.

INTERVIEWER

What was it like to allow yourself, in The Accidental, to turn a character into a poem sequence?

SMITH

I remember sitting down with my friend Kasia and saying, I want to do the next chapter in sonnets—what do you think about that? And she said, As long as they’re funny. Then we went on holiday to Crete, where, because I didn’t want to stop working, my task was to write one sonnet a day, sitting on the balcony under a canopy, when it was too hot to sit in the sun, putting sonnets together. I came back from my two weeks away with the chapter written. Margaret Atwood once said to me, with a wise look in her eye, There are no holidays in this job. She’s right. But there are onerous tasks and less onerous tasks. That’s a chapter I enjoyed writing.

INTERVIEWER

Brooke, Astrid, Kate. You are a wizard at channeling young girls.

SMITH

Are the kids more vivid than the adults? I don’t think I have a particular talent in that respect. With any luck, they all work, all the characters. But what is it about our generation, which is really attached to—and really attracted to—the child form of ourselves? We dip into stupefied and stupefying nostalgia all the time.

INTERVIEWER

In There but for the, you linger over what surely must be one of the most awful dinner parties of all time. Do you think of yourself as a satirist?

SMITH

I don’t think of myself as an anything.

INTERVIEWER

You satirize celebrity culture in that book—and also event culture, yob culture, the sorry state of care for the elderly. Were you feeling feisty?

SMITH

I started the book just before my father got really ill. I wrote the first section and a tiny bit of the second section—and then he died. He died in September. I came back to the book in February and finished it by June—and it was a different book. The book was made on the fury of mourning. That’s its energy—can mourning be feisty? Life force regardless. What I discovered, though, writing it, is that work is trustworthy and loyal and underlies and overlies everything and can hold steady even as we ourselves are floating about in pieces, as if in airless, gravity-less space travel, around some phantom of what we formerly were or life formerly was.

INTERVIEWER

How early were you able to live off of your writing?

SMITH

Well, I didn’t have kids, and for a long time we lived in a house where we were paying very little rent, and when we moved to a house and we had a mortgage, I was earning more than I had been, which was lucky indeed. So I’ve fallen lucky, on those times in my life. It could have been very different. It might still. I remember editing a book of fiction by writers who happened all to be women, one piece of writing for every year of the twentieth century, and the sobering biographies, how many of those writers, celebrated in their prime, died in poverty.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think a fiction writer can be an advocate through fiction?

SMITH

Only for fiction.

INTERVIEWER

I’m thinking about Public Library, which is interspersed with prolibrary lobbying, as it were. But those are nonfictional elements between the stories. Can you write fiction that serves a cause?

SMITH

Fiction is political. Fiction can’t not be. But to set out to write anything political means that it’ll be political and not itself. Fiction tells you, by the making up of truth, what really is true. That’s all fiction writers can do. If you ask anything of fiction other than fiction, fiction won’t be able to do it. Or it won’t be good enough, it won’t work.

INTERVIEWER

I’m thinking about Else in Hotel World. You seem to have an instinctive sympathy for people on the margins—the poor, the traumatized.

SMITH

I grew up on the margins, I inherited all the value of the margins. I know from all my reading and living that extraordinary things happen on the edges—the changes happen, the rituals happen, the magic, for want of a better word, happens on the edge of things. Everything is possible at the edge. It’s where the opposites meet, the different states and elements come together.

INTERVIEWER

Your mother was Irish and your father English, but you were born and raised in Scotland. Are you a Scottish writer?

SMITH

Yes.

INTERVIEWER

Are you a nationalist?

SMITH

I’m not. I don’t like borders. I like edges, but not borders. I can’t be a nationalist. I can’t be a nationalist by dint of the foul history of nationalisms. And I don’t believe in a separate anything. Though given the UK’s decision to leave the EU, and the Tory inability to mend any of the social divisions that have become so visible here, or even truly to address them, and the shift of rhetoric in the UK concerning immigration and the refugee crisis, alongside the international and unchecked rise of the right, right now I’d vote yes, to give Scotland its already-made choice to stay in Europe—in other words, to leave the UK and stay in solidarity with the larger European Union. And I’m Scottish, as Muriel Spark says, by formation. It made me, and it’s made my writing. I remember seeing Alasdair Gray and James Kelman read in Aberdeen when I was about nineteen. I knew while I sat there in the audience, at that age, that after I heard them read, I could, we could, anyone could, now write anything—it was all possible. That’s what it was like, my Scottish formation. I grew into, was formed by, a literature that demonstrably celebrated multiplicity of voice, celebrated the margins—you just have to flick through a book by Gray to see what he does with the margins—celebrated multiplicity of and openness of form. Anything, everything possible, up against the conventional odds, revealing the oddness of the conventional, blowing the conventional out of the water. That’s my literary inheritance.

INTERVIEWER

Do you claim part of an Irish heritage, too, as the result of your mother?

SMITH

No. But if my father was the great true-ghost-story teller, as it were, my mother was the mystic maker-up of things, or revealer of hidden things. After my bath on Saturdays—she did this for the boys as well, I know because my brothers have talked to me about it—she would wrap me up in a towel and sit me on her knee, and she would suddenly become other characters. She would morph into someone else, someone imaginary, with a very real voice. It was absolutely terrifying. And if she didn’t become one of the people, she would be singing these dreadful, dreary, Victorian songs about dead children. Like Katherine Mansfield making the girls cry by reading Dickens in sewing class, she wanted to make me cry, or to fill me with suspense.

INTERVIEWER

You mention Katherine Mansfield. Is she someone who shaped you as a writer?

SMITH

I came later to Mansfield, but I love her writing. In 2002 or 2003, Penguin asked me to do an introduction to Mansfield’s short stories, for a deadline four months away, and I thought, gamely, having read In a German Pension and remembering it was slim, Oh, there’s only a few of those, I can easily do that in four months, I’ll say yes. It took me four years. I had never read her properly before, and I didn’t understand at all what I was reading, though I knew it was charged with vitality, so much so that it gave off little shocks, like electric charges. But how and why? I couldn’t get near the layeredness of her technique. It rebuffed me, or I rebuffed it. Until, by chance, we went to Brazil for a festival and I was lying, jet-lagged, in bed in the hotel and started reading Mansfield to get me through the jet lag. And then I felt at home in it, her writing, in an astonishing way. I felt understood by it, and I understood anew—with Mansfield, it’s all about exactly that—distance, foreignness, knowing you’re out of place or in limbo, between countries, selves, times, people, psychologies, histories, and however much you feel at home, you’re fooling yourself, and however strange you feel in the world or in the work, it’s natural, it’s the most natural thing. I love Mansfield. So cunning, so sensitive, hair-trigger sensitive in language, to all the layerings and performances, social, psychological, instinctual, all the things it’s impossible to articulate—in the merest exchange—and so sharp to the edgy aliveness of all things and especially language, the wild aural world. Life, vitality shines off her writing and all through it, and that life was form changing for the story as well as revitalizing.

INTERVIEWER

How about Virginia Woolf?

SMITH

Something’s happened to me since reading and loving Joyce when I was a callow student, when I thought Woolf mildly interesting and Joyce a universal. When I go to read Woolf now, she’s more convincing, more assuring and more unassuring both—more true and more testing to me now.

INTERVIEWER

Angela Carter?

SMITH

Because I was doing a piece of work about her, I read chronologically everything she’d published, and the payoff of reading Carter chronologically is that after those early, foul, dark, funny, shark-toothed books, you get to end with Wise Children, which is a triumph of life. Imagine going out on that huge kindness and transformation of vision, from brilliant cynicism and darkness to a brilliant fertility and lightness.

INTERVIEWER

Sebald?

SMITH

Woolf and Sebald, remaking the novel, equally. Austerlitz—the most uneasy novel I’ve ever read, a novel uneasy with the very notion of being a novel. I read all of Sebald’s books again after his death, and it was very different from reading them when he was alive. He is utterly despairing, particularly in The Rings of Saturn. It’s terrible, beautiful, and there’s no hope. And then you get to Austerlitz, and in Austerlitz despair is ultimately a fiction, too.

I went for an interview for a fellowship at the University of East Anglia in 1998, and I got met at the office by a man called Max—a very nice German man who took me along the corridor to the interview and who sat in as onlooker. That night, I got home, I went to bed—and I woke up in the middle of the night, going, Oh dear God—was that Sebald? I had read The Emigrants and The Rings of Saturn, I was a fan. I got that fellowship and saw him a couple of times over the months I was at UEA. So as it happens, I knew him tangentially. What I know, even just from that tangent, is that he was an incredibly charismatic figure, he was like no one I’ve ever met. Plus, not many people know that he was funny, funny, funny. He was laugh-out-loud droll. We haven’t begun to understand his rigor yet, as a writer.

INTERVIEWER

In Artful, you write that the difference between the short story and the novel is their relation to time and that short stories will always be about brevity.

SMITH

Both the novel and the story are about time. But the novel is about continuance, and the story is always about how fast it’s going to be over, which means that the story has a special relationship with mortality. That is why we’re so attracted to them, and also why people find them very, very difficult, because built into the form is the fact that they’re over so soon, that soon they are going to end, like we know lives are going to end. Novels don’t do that—they can’t do that. They might be dealing with death, but one way or another, they’re about sequence.

INTERVIEWER

What about when you have a short story with three different events, as some of yours do? Where is the line between short story and novella or novel?

SMITH

Those moments will resonate, they will send an echo back and forth. That’ll happen in the novel also, but other things will be happening in the novel, too. Because the novel deals with time in continuity, it also deals with the shape of whatever society its characters inhabit, with the shape that our living takes and is taking. A story doesn’t have to do those things, although it can.

INTERVIEWER

I was wondering if you could take one story and talk me through from the beginning of the writing process to the end.

SMITH

Have you got a story in mind?

INTERVIEWER

“Being quick,” which has that classic Ali Smith switch between perspectives.

SMITH

That story has, somewhere near its start, the phrase “Death was unexpected.” That’s where the story began. I remember thinking, What would an unexpected death look like in person? Somebody wandering about King’s Cross station in a white suit, say, who looks rather like a BBC executive? That’s unexpected.

Then there are the two lovers in the story, one at home and the other at a station getting on a homeward-bound train. People quite often, several times a year, throw themselves in front of trains on this line. If you travel from King’s Cross north, a couple of times a year you’re going to be on a train that is held up by one of those deaths. It’s terrible. You are—what should I say?—put out by it. An awful feeling, that a death would put you out. You’re on the train, the thing happens—the unexpected death—and you experience around you the selflessnesses and the selfishnesses of everybody in the carriage while you’re waiting to get past, to get home. Life going on, in all its triviality and mess, regardless of the death.

And as soon as you have a love story, there’s the question of the loss of the love. It doesn’t matter where you are in the love story, the question is always there. So that tension is also holding at the center of “Being quick”—the person not there and the person there. And the maddeningness of the lover, also there as soon as you have a love story.

I remember trying to calculate how long it would take you to walk if you got off that train, from wherever to wherever. Also I love the word quick. Because quick means “fast” and “alive.”

INTERVIEWER

Here’s a sentence from that story—“I stared over his head at the lightly dusked outskirts of London, at its weeds, its graffiti, its small squares of fast-passing light, the early evening windows of the lives of hundreds of others.” Remember writing it?

SMITH

Nope. But I remember the weeds. I can see them now. Buddleia.

INTERVIEWER

I love “lightly dusked.” Or is that too rich for you?

SMITH

No, no. I love rich. The richer the better. Nobody takes a rich risk anymore. Why would we not? Language is endless currency. Shower me with words like that girl in the myth gets showered with coins.

INTERVIEWER

How long do you think it took you to write “Being quick?”

SMITH

A couple of weeks. I can more clearly remember the time they took to write than I can remember their titles sometimes. The longest it’s ever taken me to write a story is eighteen months, the one called “The hanging girl.” Horrible story to work with. And I put it off, put it off. The shortest took an afternoon, and that was . . . oh God, what’s it called? “Believe me”—the one that starts with the person saying, “I’m having an affair.” I was writing something else instead and was dissatisfied with it, and when I stopped and put it aside and wrote a couple of lines of the something else that turned into that “Believe me” story, it came out. For weeks it had been quietly forming its form while I messed around with something else.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me more about “The hanging girl.”

SMITH

It came from a picture of a hanging in Minsk, a public hanging, and I couldn’t get it out of my head—I still can’t get it out of my head. I saw it in the newspaper, a supplement of the Guardian. I turned the page and saw this picture. I thought, What right have I got to be seeing this person’s death? It was a picture in segments, so you saw just before, during, and after the hanging of the girl. And someone hanging next to her, already dead, and the next person waiting to be hanged. It’s foul. Really, really foul. I felt like a heel for opening a paper, no, for being able to just open a paper in the future and witness so freely the moments of someone’s wrong death. That’s where that story comes from.

INTERVIEWER

You brought it from Minsk to contemporary Britain and made it the catalyst in the breakup of a love story.

SMITH

The love story is the nonstory in that story. It’s the nothing. It’s the distraction.

I had a fellowship in Canada in the spring of 1997, a really good Scottish Canadian fellowship, based that year at Trent University in Peterborough. I had three or four weeks by myself, sitting in this room, nothing but snow on the campus, blizzards, and I wrote the beginning of that story, just the monologue piece, and it wasn’t quite right but I was getting there, I was getting something. And then I stopped—I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Every time I would go back to the story between other things, it would shift a little bit. The second catalyst was watching Friends on TV and thinking what culture is like, to have held, like it does, in the same space, some episode of Friends and those pictures of the death in the paper.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve done several stories in the second person. What’s the attraction?

SMITH

There’s a great Scottish writer called Lewis Grassic Gibbon, a northeast writer, and when I was at school, we were made to read his book Sunset Song. I know now I owe immensely to Lewis Grassic Gibbon in everything I’ve ever done. He writes a sentence so long and so rhythmic that you know it’s coming from thought, and from the breathing apparatus, rather than the mouth. He writes from the beat of the heart and the mind in tandem. He writes so ironically and funnily about community. So brilliantly about women and men. The novels are modernist, though they ape and claim an older tradition, too, and are largely written in the second person. He uses “you” in a way which goes into me like a sponge. You can do anything with his “you”—it implies a distance, which is useful, and it implies an intimacy, which is useful. He uses the “you” to mean the reader, so that there’s always communication between “you” and the person holding the book. And the implications for communal form are stunning—“you” becomes the whole plural community, and “you” the individual within the community, and “you” the individual up against and separate from the community, a separate “you.” And that’s just the start of what he does with second person. This kind of layering is for sure one of the reasons I write anything.

INTERVIEWER

The narrator of “Good voice” wants to work on a project that’s “about voice, not image, because everything’s image these days and I have a feeling we’re getting further and further away from human voices.” Is that a standard writer’s complaint?

SMITH

I think that comes particularly from trying, in 2014, to write a story about the First World War, one of those commemoration stories, a commission. The more I saw online, the less it meant. There was something terrifying, literally, about the ways in which the images just came up on the screen. Click, click, click. I remember thinking that we were emptying ourselves of meaning via the image—especially on the screen, where an image is digital and will just disappear. The key motivation for “Good voice” is the difference between voice and image—at which point my father’s voice, in my head, simply came in. The First World War exists, for me, through the voice of my father, who wasn’t in that war but for whom it vividly existed through the voice of his own father, who was gassed twice in that war and died young because of it. I never did hear the voice of my grandfather, which my father had so clearly in his head, exactly like I have his voice in mine. I was thinking about that.

INTERVIEWER

Is the story of you and the short story about the gradual jettisoning of all rules? As the storytelling narrator says in “Fidelio and Bess,” “Actually I can do anything I like.”

SMITH

If you can’t ask questions of a structure, then why are you even hanging around the structure? That’s how we find out what structure is and why it takes certain forms and why it doesn’t take others—by asking why it’s the shape it is and what happens if you bring other shapes to it.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a political valence to experimentation with literary forms?

SMITH

There’s political valence to everything, whether we know it or not, whether we think we’re acting on it or not. You can’t not be a political being, even when you’re announcing that you’re not a political being.

INTERVIEWER

So how conscious is your political impetus when you’re—excuse the language—fucking with the structure?

SMITH

Don’t be excusing language. It’s not conscious in the act. If it was, the story wouldn’t be story. In the act, all you can do is make the story that asks to be made the way that it is asking to be made.

INTERVIEWER

“The short story is a cage in search of a bird.”

SMITH

Franz Kafka. The life of the short story is always escaping the short story. Or, the door to the short story is always open. There is the structure, but you know that there’s a life somewhere in it, around it, free from it.

INTERVIEWER

How did your current project, the quartet of which Autumn is the first installment, come about?

SMITH

The writer Olivia Laing—I’ve known her for years, because we’re cousins-in-law, she’s Sarah’s cousin—came around last May or April. She knew I’d started working on the books about the seasons, and she said, Look at this, and flourished a blurry photograph of one of our old cats, now long gone to heaven. On the back of it was a letter I’d written her in, like, 1996, which said, I think I want one day to write four books about the seasons. That was twenty years ago. I was relieved. It was proof that my thinking about them for all those years wasn’t just a fantasy. But I’d thought I would do them when I was old. After How to be both, I thought, It’s time. Why don’t I do them next? So I must be old now.

The idea was always that the books would be about longevity and, at the same time, about the surface of whatever was happening in the world at the time the book was being written. In December 2015, when the referendum on EU membership was nothing but a twinkle in a Euroskeptic politician’s eye, I was beginning to get down to work on the actual writing of the first book. And I was writing it and writing it and stuff was happening—and all of a sudden, in June, the EU referendum. I couldn’t quite believe how little time they gave it, considering how thorough, how carefully argued and thought through the referendum on independence in Scotland had been. Anyway, I was traveling around bits of Southern and Northern England in the run-up to the vote, and the massive support for leaving in these places was everywhere, in a way that London, say, and Cambridge, where I live, had no real idea about or inkling of. And we sensed what was coming, even though we were hoping it wouldn’t happen. At least I was hoping it wouldn’t happen. But the great shock of it was in the air, and after it happened I thought, This book has to meet the contemporary head-on or there’s no point to this sequence of books. I looked at the text I had, and it already featured some motifs which run through the finished work—like the fence—and at the back of the story was always the great mass movements of people across all the histories, all the way back to Homer and beyond, but particularly across the history of the last century.

INTERVIEWER

Were you pleased to see Autumn referred to as “the first serious Brexit novel”?

SMITH

Indifferent. What’s the point of art, of any art, if it doesn’t let us see with a little bit of objectivity where we are? All the way through this book I’ve used the step-back motion, which I’ve borrowed from Dickens—the way that famous first paragraph of A Tale of Two Cities creates space by being its own opposite—to allow readers the space we need to see what space we’re in.

INTERVIEWER

Is it harder to write fiction in our “post-truth” era?

SMITH

We are living in a time when lies are sanctioned. We have always lived in that time, but now the lies are publicly, rhetorically sanctioned. And something tribal has happened, which means that nobody gives a shit whether somebody’s lying or not because he’s on my side or she’s on my side. In the end, will truth matter? Of course truth will matter. Truth isn’t relative. But there’s going to be a great sacrifice on the way to getting truth to matter to us again, to finding out why it does, and God knows what shape that sacrifice will take.

INTERVIEWER

What’s next, Winter?

SMITH

It’ll be chronological. But all these books will be about other seasons regardless of what they’re called. Winter won’t really be about winter. You can’t have any of the seasons without the other seasons. All seasons exist within each season.

INTERVIEWER

Could you do a linear plot if you had to?

SMITH

No, I don’t think I could. Something always gets twisted. And I think that’s a part of the life force of it. Because time is not linear.

INTERVIEWER

It occurs to me that your insistence on the nonlinearity of time may have something to do with all the ghosts in your fiction.

SMITH

I just don’t think death makes that much difference. We carry with us all the people who have made us and the people we make and the lives we make, and the world we make continues on from what we make of it.

INTERVIEWER

Sounds to me like wishful thinking.

SMITH

Wishful thinking is all we’ve got—if we’re not thinking wishfully, then what a waste of thinking. I don’t mean that in a naive way. I was brought up in a postwar world that said, This has got to be better. We’re going to have to make this better for everyone. I inherited that wishful thinking. The notion of protest, which we inherited, is the thing we’re going to have to reinherit.

INTERVIEWER

What would you do if you couldn’t write?

SMITH

Write musicals.

INTERVIEWER

Would it be of any use to connect your work with the tradition of modernism?

SMITH

I’m lucky to have loved it. I love the way the reader was made to be involved, so that reading a text became itself a creative act and reminded you at every point that we make the world. At university, we read chronologically from Old English onward. In the final year, fourth year, when we got to modernism, particularly American modernism, I knew I was home. Dos Passos, E. E. Cummings, Fitzgerald—we did a course which was culturally very playful, which involved music and all the arts.

INTERVIEWER

You use the word “playful.” I would say your books are endlessly playful, alive with puns and verbal hijinks and layering and patterning. Do you think of writing as a kind of play?

SMITH

No, but I love the idea that it is. Actually, it’s work—it’s really work. When you have to produce something, and you know you’ll get paid for it, then that’s why you do it, because it pays the mortgage. And because of the work ethic put into me by my parents. Simple as that. But I love it when Christine Brooke-Rose takes the phrase let us pray and changes it to “let us play.” Brooke-Rose, one of the true experimenters of the twentieth century.

This may be more wishful thinking, but there’s a point—let us play—at which language is acting on another layer, on a resonance like a halo, the place where we understand something doubly or triply, and in that recognizing we understand a communal connection, between us and language and between us and others. It’s like being tickled and like being understood as a thinking being in the world, both at once—which is why I love puns. Puns were originally sacred. If you look back at the beginning of the writing down of language, in sacred rites, puns are everywhere. Ritualists in religions used puns to mark the important, the holy, or the sacred places in the ceremony. A pun heralds or marks the point at which transformation takes place, where a magic thing happens.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have an idea what the other three novels in your seasonal quartet are about?

SMITH

I already have in my head the movement of it. However, this time last year I thought Autumn was going to do one thing, and it did quite another thing in the end. And I don’t know what the world will bring. This is the darkest time in our lives. It’s utterly awful. What are we going to do?

INTERVIEWER

I’m not sure that this is Paris Review material.

SMITH

Doesn’t matter. We’re not just here for The Paris Review.

INTERVIEWER

True, but somebody has to transcribe all this.

SMITH

Hello, transcriber! Thank you for your transcribing.

No comments:

Post a Comment