|

| Family and Rainstorm, 1955 Alex Colville |

AGO's Alex Colville exhibit aims to enlighten but manages to exhaust

PUBLISHED AUGUST 22, 2014

It’s usually a huge disappointment when a survey of a major artist fails to include a work or works that a viewer believes should be there. How authoritative and essential would a Tom Thomson retrospective be without The West Wind and The Jack Pine? Ditto a van Gogh exhibition minus The Starry Night, or a Manet sans Le déjeuner sur l’herbe from the Musée d’Orsay.

No one is going to complain about such absences in Alex Colville, an exhibition of paintings and studies by the man who, before his death last summer at 92, was Canada’s most famous living artist. Opening Saturday at the Art Gallery of Ontario for a run through Jan. 4, the show spans his entire career, includes more than 110 paintings culled from public and private collections across the country, and sprawls over several galleries in the Zacks Pavilion on the AGO’s second floor. The Toronto gallery hosted the first major retro of the artist 31 years ago, a two-month-long showcase that went on to tour other Canadian centres, as well as venues in Germany, China and Japan.

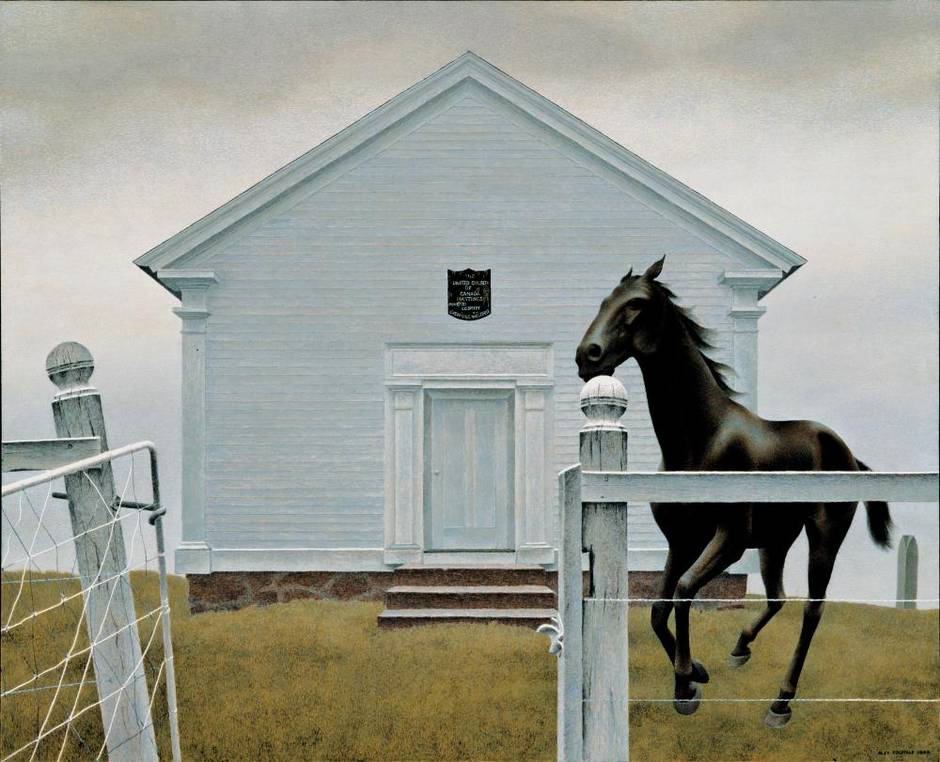

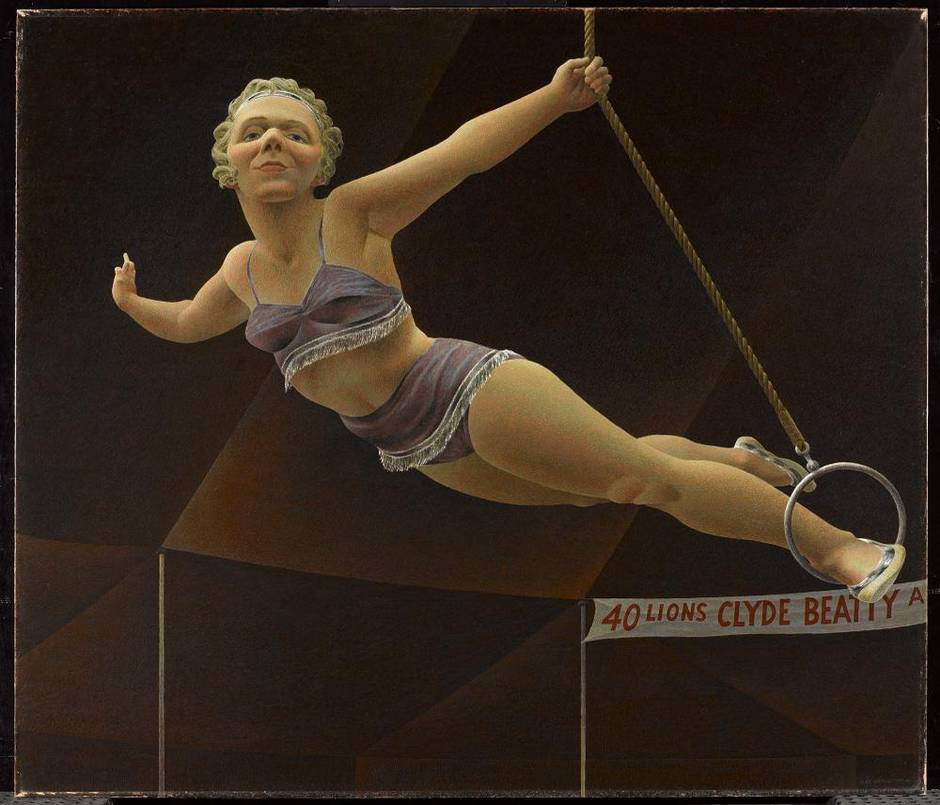

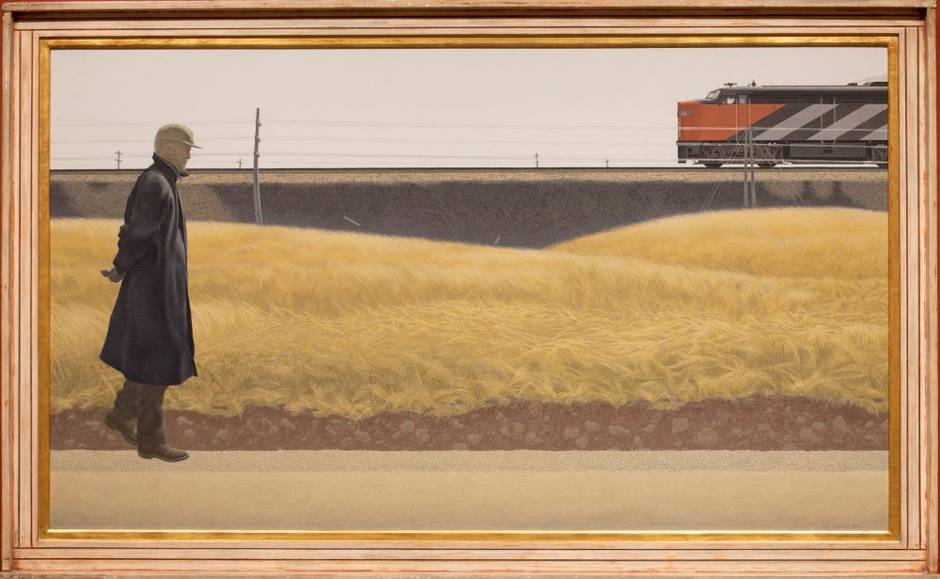

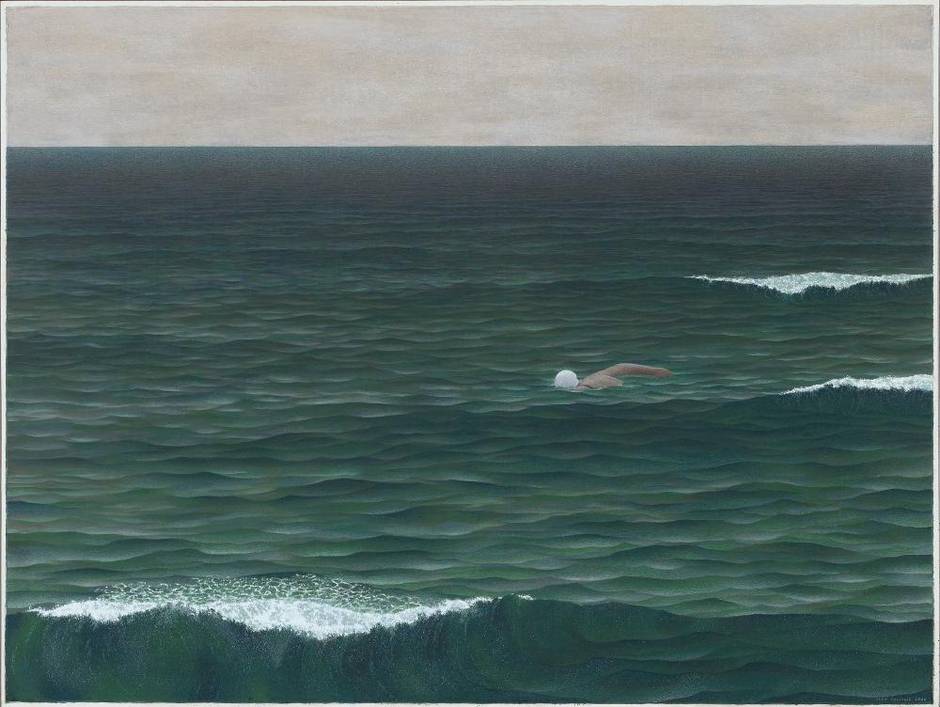

Of course, there are gaps – I don’t recall seeing In the Woods, from 1976, for example; or 1954’s Three Sheep; or Man on Verandah, the 1953 tempera on board that sold for close to $1.3-million in 2010, the most valuable Colville ever sold at auction in Canada. But this is just nitpicking. For a decidedly irreligious man, Colville had a knack for producing precisely rendered iconic images, and pretty much all of his greatest hits are gathered here. They include Horse and Train, To Prince Edward Island, Pacific and Dog and Priest, as well as quirkier, less familiar pieces like the Felliniesque Circus Woman from 1959. There are five works never before seen in public, including Woman with Clock, a 2010 acrylic of the artist’s wife and long-time muse, Rhoda (she predeceased him by six months), generally deemed to be Colville’s last painting.

It is, in fact, this feeling of completeness that is perhaps the exhibition’s biggest flaw. Colville was a singular talent. But, in its very plenitude, the AGO show makes the case for an artist best consumed and appreciated in small doses.

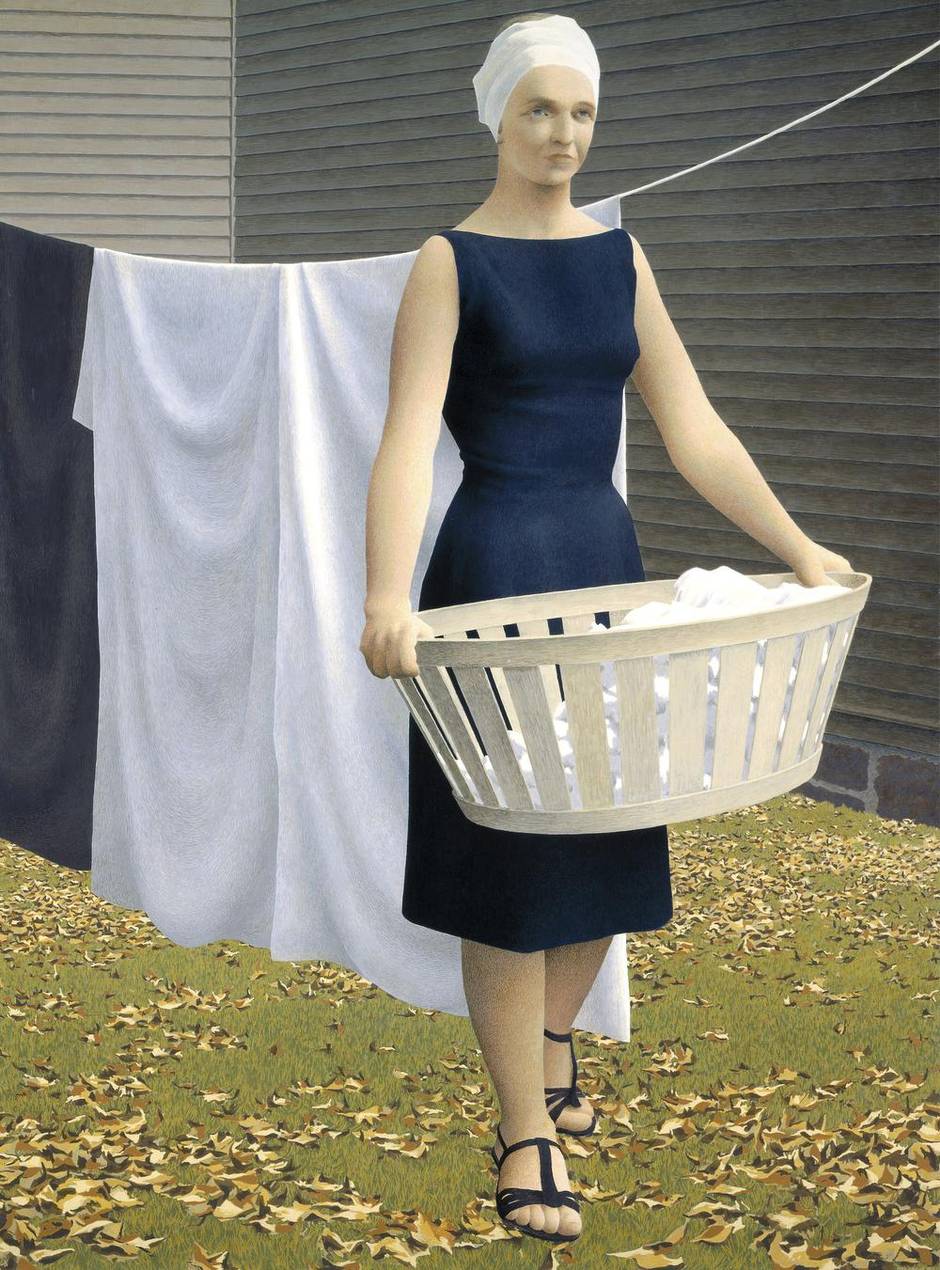

Doubtless many Canadians can remember their first encounter with a Colville and the thrall in which they were held. But almost 65 years after the artist finished what he considered his first truly successful Colville painting – Nude and Dummy, also on show here – repeat encounters in such a grand survey affirm the law of diminishing aesthetic returns. In short order, the persistent rectitude of Colville’s palette, the geometric rigour of the compositions, the finickiness of his brush strokes (profligate in number, stingy in application), the impasto-bereft surfaces of the paintings, their atmosphere of existential melancholy and constipated terror, the artist’s fondness for freezing a painting’s action in media res – all induce not so much reverential contemplation as a kind of fatigue.

Indeed, had this show been trimmed by 30 per cent (at least) and the balance hung in tighter proximity, its cumulative effect would have been more potent, not less. And it certainly would have been more in keeping with Colville’s repressed, buttoned-down, Apollonian aesthetic. (One of the funniest artifacts in the current exhibition is A.C. Little’s 1990 photograph of Colville, in suit and tie on a summer day, walking along railroad tracks with a dog – two quintessential Colville tropes.)

Andrew Hunter, the curator both of the show and of Canadian art at the AGO, says he went into its assembly determined to present the Colville oeuvre less as a “memorial” or “closed book” than as an argument for Colville’s “ongoing” and “deep relevance” as a “significant artist.”

To militate against the works’ sheer familiarity, Hunter employs two strategies. One is to arrange the Colvilles by theme rather than chronology. Thus, there are sections with such titles as Of Light, Love and Loss; Home from Away; and On Good and Evil.

The other is to position, at various junctures, a series of what he calls “responses” and “echoes” by other artists, living and dead. They include William Eakin’s monumental photographs of the six fauna-themed coins Colville designed for Canada’s centennial; a 2013 colour-pencil drawing, titled Hunters, by the late Cape Dorset artist Itee Pootoogook; a looped clip of a beach scene from Sarah Polley’s autobiographical 2012 film Stories We Tell; and an eight-page comic book, Colville Comics, by Hamilton-based David Collier who (like Colville, in his case, during the Second World War) served as an artist for the Canadian military.

Another short loop is from a tense scene in a Texas suburb near the end of the Oscar-winning No Country for Old Men. Colville thought Joel and Ethan Coen were “great filmmakers,” according to his daughter, Ann Kitz. He liked the way the brothers captured a sense of events “going along very smoothly” on a sunny day, then suddenly turning “horribly wrong.”

Hunter’s first strategy, while not altogether successful (it’s finally like shuffling a well-worn deck of cards), does result in some artful juxtapositions. One my favourites involves the pairing of the female nude in Colville’s 1987 film-noirish Woman with Revolver with the equally noir nude Dressing Room from 15 years later. Guns, of course, are a Colville motif. (If there isn’t already an edition of Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus – which begins “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide” – with Pacific or Target Pistol and Man on its cover, there should be.) And it’s carried even into the show’s amply stocked gift boutique, which offers a revolver keychain for $9; and, for $27, a notebook with an embossed pistol on its cover.

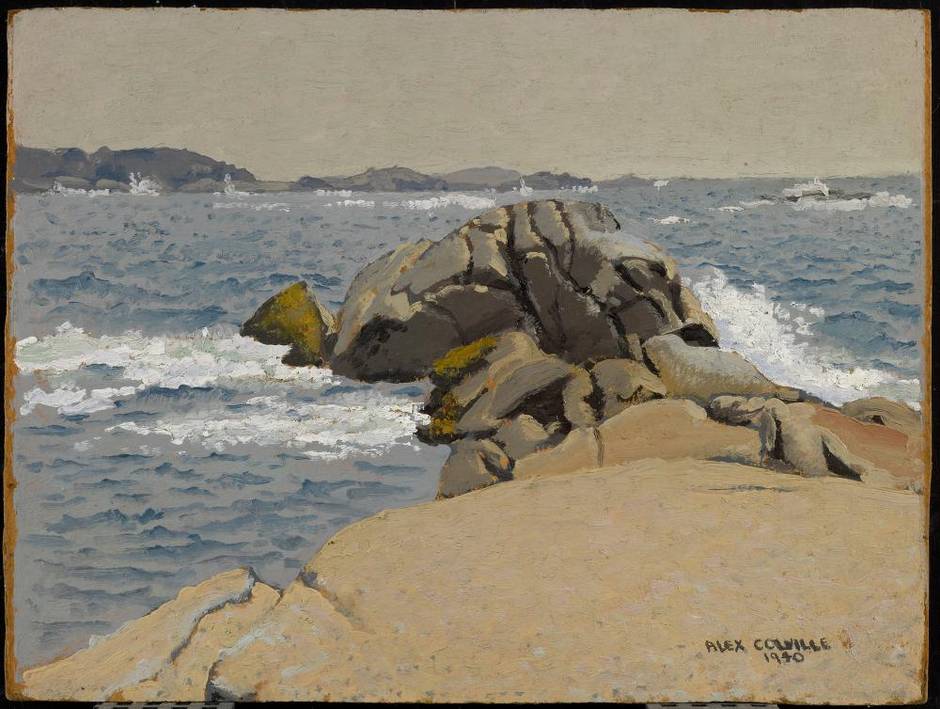

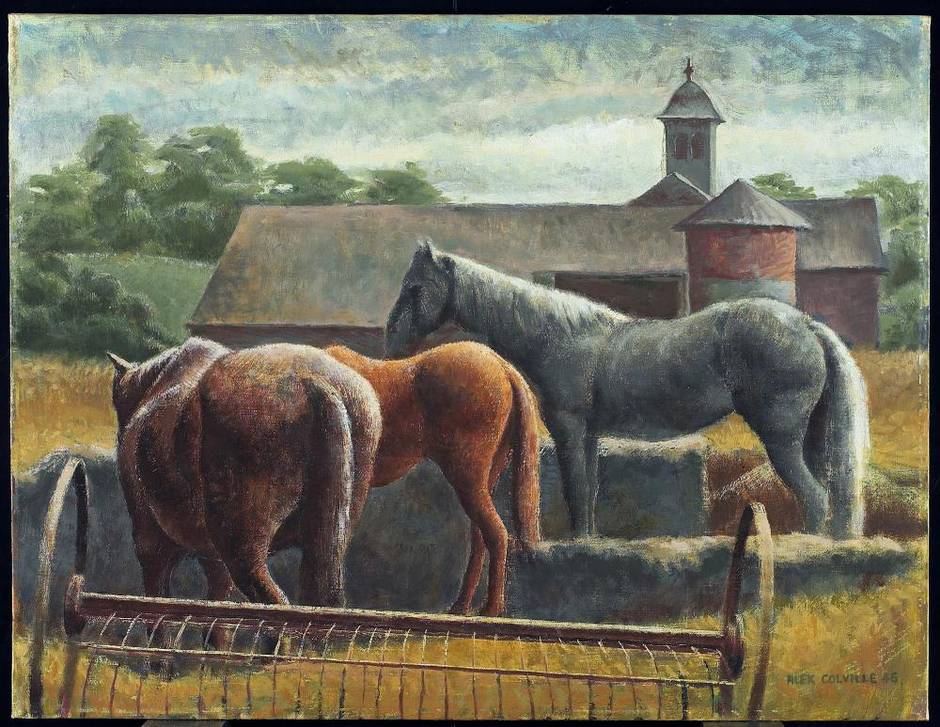

In some respects, the most interesting works in the exhibit, at least from a purely painterly perspective, are the early ones – among them a couple of self-portraits from the 1940s; and scenes of the Second World War. The latter include, of course, depictions of the horrors of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp that a 24-year-old Colville witnessed, to life-searing effect, in April, 1945. Content-wise, these paintings are already distinctively Colvillean. To paraphrase Marc Mayer, CEO of the National Gallery of Canada: Alex Colville always was Alex Colville. Yet, the brushwork is refreshingly looser, less refined; the compositions airier and not as beholden to the strictures that came to jacket Colville’s mature work.

As for Hunter’s second strategy, it’s decidedly more interesting than the first, but frustratingly so. While its notion of “anticipations,” “responses” and “echoes” more successfully realizes the ambition of updating Colville’s artistic currency (rather than stranding him, as the art establishment did from the late 1950s into the early eighties, as an eccentric cul-de-sac doomed to history’s dustbin by the grand sweep of abstract expressionism, pop, and conceptualism), it’s realized with insufficient breadth and depth.

Certainly the conceit begins excitingly and enticingly enough, with Hunter positioning, at the exhibition’s entry, Colville’s 1965 classic To Prince Edward Island alongside a 10-second loop, from Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom (2012), of actress Kara Hayward staring worriedly through binoculars while atop an apparent lighthouse. This doubling, with its suggestions of surveillance, isolation, Hitchcockian tension, unknowability and voyeurism, motion and stasis, creates an anticipation that’s only fitfully realized by the rest of the show.

For instance (through no fault of the AGO), Warner Bros. refused permission to run those excerpts from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining in which no fewer than four Colvilles (Horse and Train among them) appear. As a result, a gallery visitor is left to simply stare at those paintings and try to imagine their cinematic resonance via text panels outlining when each of the Colvilles appears and what’s happening narratively when it does.

Still, the idea, at least, was a smart one. And proceeding through the exhibition, you’ll likely be hankering for more examples of that kind of thinking, even if their realization might have meant fewer paintings of dogs, bridges, cars, and humans with their faces supplanted, averted, cropped or otherwise obscured.

Perhaps, too, had the AGO given itself extra prep time, it might have sourced more interesting and eclectic artists for compare-and-contrast purposes. The gallery’s inclusion of hyperrealist paintings by Christopher and Mary Pratt is entirely apt but also entirely predictable. The show would be a lot cooler and hotter had the AGO scored, say, The Old Man’s Dog and the Old Man’s Boat by Eric Fischl, with its suburban sexual raunch; or one of David Salle’s mid-eighties provocations; or a loan of Cindy Sherman’s creepy Untitled Film Still #48, depicting a solitary woman at dusk, seemingly stranded with suitcase, beside a deserted highway.

As it stands, the exhibition affirms, if such affirmation is needed, Colville’s stature as a Canadian original. However, as a machine for recasting or revaluating what the artist himself called the “authentic fictions” of his oeuvre in light of contemporary art practice, it is something of a missed opportunity. Or as Hunter prefers, in his introduction to the show’s catalogue, a “beginning rather than ending.”

No comments:

Post a Comment