Why does Nicole Kidman undress in the opening shot of ‘Eyes Wide Shut’?

Stanley Kubrick’s last project Eyes Wide Shut (1999), which features Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise as a well-to-do Manhattan couple whose marriage is in trouble, is a cult work. It had a mixed critical reception on its first release, but since then its reputation as one of the director’s finest works has grown. The film is controversial for many reasons — as much to do with its production and reception as for its supposedly sensational sexual content, heavily hyped by Warner Bros. Like so many Kubrick films, Eyes Wide Shut confounds expectations and tests viewers to the limit. The director was a perfectionist and his attention to detail is legendary; one of the fascinations of his work is the pleasure of unpicking every nuance of image and sound in search of a definitive meaning — a quest destined to be frustrated. This is cinema for obsessive compulsives.

The film is a costume extravaganza that plays on identity and sexuality. Cruise’s Dr. Bill Harford is on the surface a devoted husband and father who inadvertently gets involved in a ritualistic orgy at a masked ball. He’s drawn into a series of unfulfilled sexual encounters that strip away the veneer of his respectability and masculinity. The trigger for his descent into the depths is an argument with his wife Alice (Kidman) in which, after accusing him of not understanding women’s needs, she reveals an erotic fantasy in which she has sex with a young naval officer she once glimpsed in a hotel lobby. Bill is provoked into seeking extramarital excitement himself, and the film stages his fantasy scenarios, which are fraught with anxiety. His misadventures are rooted in disguise and deception, and the fragile underpinning of his life gradually disintegrates. Finally, after the mask is dropped and the couple reconciles, Alice is very much in charge. Many critics saw Eyes Wide Shut as a portrait of the ‘real’ Kidman-Cruise relationship, which fell apart soon after the film was released. This, of course, intensifies the frisson.

The opening has been much discussed. In it, Alice is briefly seen naked from behind as she steps out of a black gown in her bedroom. She and Bill are getting ready to go to a party, and we see the couple in the bathroom together, with Alice sitting on the toilet. When they’re ready to go, Bill turns off the radio and the light in their bedroom as they both leave. This short sequence is complex and has been interpreted in different ways. Here I want to focus on the contribution of costume to the layers of meaning. Eyes Wide Shut is about the multiple implications of dressing and undressing, a theme set up in the first few moments.

As the stark black and white credits appear on screen, Shostakovich’s ‘Waltz No. 2’ plays on the soundtrack. The first shot is of Alice, who is wearing no underwear, dropping her black dress and stepping out of it in high court shoes, giving two little kicks to get free. The shot is deliberately voyeuristic: the dressing area, framed by pillars, is brightly lit, while the viewer is placed outside the space in the shadows at the front. There’s a clear boundary between viewer and spectacle, similar to that experienced in the theatre or cinema.

There’s another boundary too, a cinematic device that puts the shot in parentheses, or quotation marks. The shot, which lasts about six seconds, is sandwiched between the director’s name and the film’s title. It’s a fetish object, cut out from the rest of the film and designed to be replayed and pored over. It exists in an imaginary dream space, accompanied only by Shostakovich — narrative sound is heard for the first time with the next shot of the city streets.

The dream ambience is appropriate: Eyes Wide Shut is based on Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 novella Traumnovelle (Dream Story). Who are the dreamers here? Stanley Kubrick, for one — he’s stamped the shot with his mark of ownership. Viewers, too, as they linger in the half-light watching Alice’s private moment. And Bill. In the next interior shot we see him, a shadowy figure in the darkness of the dressing area, emerge into the well-lit space of the couple’s bedroom and bathroom. In contrast to the tableau shot and framing of Alice, the camera is now mobile, moving through ‘real’ space as though we are there with the characters, as the Shostakovich waltz plays on the bedroom radio. Even more intimately, we are invited into their bathroom to see Alice in non-erotic mode taking a pee, wiping herself and pulling up her panties. Now she’s wearing underwear, and she has on a different dress than the one she discarded in the opening shot.

Because of the way the opening shot is positioned, it looks as though it’s out of sync with the scene of Bill and Alice getting ready to go out. Is the darkened dressing area the same space in which we saw Alice undress, and is the time frame the same? The tennis rackets in the corner are no longer visible, and there are bookshelves we couldn’t see before. There’s not necessarily a break in continuity: the rackets could be covered by Alice’s discarded black gown, and the bookshelves may be there because the camera is in a different position. But the disconnected quality of the first shot makes the apparently familiar space of the bedroom seem strange. The dream appears real and reality appears dreamlike.

Throughout the film, Alice is depicted as a figure, even a figment in the film’s dream narrative, which is presented from Bill’s point of view. It gets complicated when Alice’s dream enters the story. Suddenly she’s the subject of her own fantasy (if it is hers) at the same time as being a character/object in Bill’s. This is the key to Bill’s identity crisis: in his psyche a battle for dominance is played out in which gender roles are confirmed, tested and overturned.

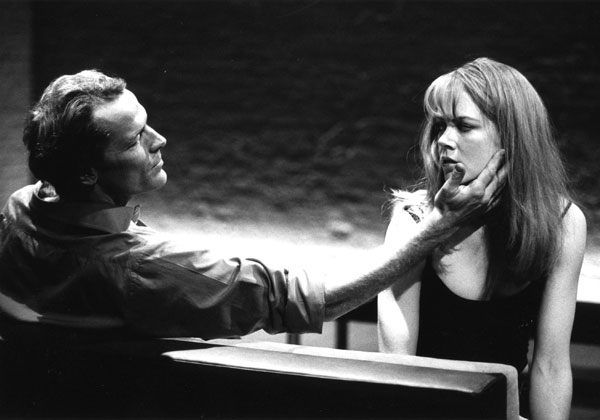

The opening shot of Kidman is a time-bomb. It teases the viewer into believing they are in control and then explodes their expectations. The intimation that all is not as it seems intensifies the desire to return to it over and over again. The brief glimpse of Kidman naked recalls her 1998 appearance in The Blue Room, David Hare’s adaptation of Schnitzler’s play Der Reigen, filmed by Max Ophüls as La Ronde (1950), in which she and Iain Glen played different characters involved in a series of sexual encounters. In one scene, Kidman appeared naked in back view for a few moments as Glen slowly dressed her — this caused a sensation and contributed to the play’s critical and box-office success.

There are clear resonances between The Blue Room and Eyes Wide Shut. Apart from the preoccupation with costume, identity and sexuality common to both, the emphasis on performance (a Kubrick motif) is elaborately worked through in the film. There are striking similarities between the poster for The Blue Room and the image of Alice looking elsewhere as Bill kisses her, widely used in promotion for the film.

The reference to The Blue Room in the film’s opening shot signals its aspiration to the play’s headline-grabbing notoriety. In both cases, there was little explicit sex or nudity on view — it was exactly this that proved so titillating. Warner Bros’ promotional campaigns exploited the film’s sensational sexual content, but many reviewers found Eyes Wide Shut distinctly unsexy. Kubrick’s joke was to entice viewers with the promise of arousal, only to break his promise by confronting them with a treatise on the impossibility of sexual fulfilment. The shot of Kidman undressing encapsulates this irony. Its endless replaying in different media forms underlines its elusive quality; it embodies the fruitless search for satisfaction at the heart of sexual desire (à la Kubrick).

Kidman is seen in various stages of undress and erotic scenarios during Eyes Wide Shut, while Cruise appears in masquerade costumes and masks; by the end, Bill is unmasked and emasculated, something that appears to excite Alice as she utters the film’s final line: ‘Fuck’. Is her power over Bill real, or is it a feature of his fantasy? Whatever the case, in Eyes Wide Shut female desire is shown to be capable of stripping away the façade of male (hetero)sexuality and destabilising the illusion of masculine power. The deceptive promise of the opening shot (Kubrick’s master stroke) lures viewers into a state of false security, ensuring that this will be a moment to return to in a film that pivots on sexual anxiety.

© Pam Cook

____________________________________________________________________

More on Eyes Wide Shut …

Dennis Bingham, ‘Kidman, Cruise, and Kubrick: A Brechtian Pastiche’, in Cynthia Baron, Diane Carson and Frank P. Tomasulo (eds), More Than a Method: Trends and Traditions in Contemporary Film Performance (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004).

Michel Chion, Eyes Wide Shut (London: BFI Modern Classics, 2002).

Stanley Kubrick and Frederic Raphael, Eyes Wide Shut: A Screenplay (London: Penguin Books, 1999). Includes Arthur Schnitzler’s novella Dream Story.

James Naremore, On Kubrick (London: British Film Institute, 2007).

It’s also worth checking out the mountain of online appreciation of the film.

No comments:

Post a Comment