Franco Zeffirelli obituary

Celebrated director of stage and screen who created lavish opera productions and brought new audiences to Shakespeare with his 1968 film version of Romeo and Juliet

John Francis Lane

Saturday 15 jun 2019

Franco Zeffirelli directing Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting in his film version of Romeo and Juliet. Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

Franco Zeffirelli, who has died aged 96, was not only one of Italy’s most talented directors and designers in the theatrical arts, but was also involved with cinema and television for more than half a century. In any medium, he generally preferred a grand canvas. His work was dominated by adaptations of the classics and lush biographies or histories, told with flamboyance and sentimentality. He had an unerring eye for attractive stars of both sexes such that, whatever their weaknesses, his productions invariably looked good.

Though he earned respect and admiration in the many countries where he worked, it hurt him deeply that in his homeland he was not always appreciated as he felt he deserved. Zeffirelli had himself to blame if he often became a target in the Italian press, the result of his mania for freely expressing his controversial views on almost every subject concerning Italian society.

Born in Florence, Franco was the son of a dressmaker, Alaide Garosi Cipriani, with an ailing husband. She had become pregnant by Ottorino Corsi, a drapery merchant, whose own wife was to persecute the young Franco for many years, calling him “bastard” in front of other children. Alaide chose the surname “Zeffiretti” (little breezes) for her son – inspired by the title of an aria from Mozart’s opera Idomeneo – but a mistake led to “Zeffirelli” being recorded.

When Franco was six his mother died, and he was brought up by his father’s cousin Lide, who was to remain a substitute mother until she died in 1968. He attended a Roman Catholic school in Florence where, as he revealed many years later in his autobiography, he was sexually assaulted by a priest. He enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence in 1938 and, in his late teens, began studies at the architecture faculty of Florence University, but these were interrupted by the second world war. The atmosphere in the city at this time was somewhat romantically recreated in Zeffirelli’s film Tea With Mussolini (1999), and his lifelong love of culture and literature stemmed from the teacher Mary O’Neill (played in that film by Joan Plowright), who gave him private lessons from 1930 onwards.

|

| Judi Dench and John Stride in the title roles of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet at the Old Vic theatre, London, directed By Franco Zeffirelli, 1960. |

After the armistice of September 1943, Zeffirelli joined a partisan group. During the struggle that followed, as the allies continued to drive the Nazis out of Italy, he came into contact with a battalion of Scots Guards, who took him on as interpreter.

Returning to Florence after the war, he decided that the theatre interested him more than architecture. While working as a scene painter, he met the director Luchino Visconti, who offered him a small part in his next stage production, Crime and Punishment, due to open in Rome, to which Zeffirelli moved in 1946.

After the run ended, he played the juvenile lead in the film L’Onorevole Angelina (Angelina: Member of Parliament, 1947), directed by Luigi Zampa and starring Anna Magnani. Instead of pursuing an acting career, he decamped to Sicily as an assistant director on Visconti’s film La Terra Trema (The Earth Trembles, 1948). He was never to regret his choice. Though irritated by Visconti’s double identity as aristocrat and communist sympathiser, he became more intensely involved with the director during the shooting of the film, and when back in Rome he moved into Visconti’s villa. Zeffirelli later said that his relationship with Visconti was one of his “serious love affairs”, in which he was “hit right on the forehead and in the heart”.

He served as “art director” for Salvador Dalí when the painter designed Visconti’s exotic stage production of As You Like It in Rome in 1948. The following year he received critical attention for his first designer credit, on Visconti’s production of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire. In the spring of 1949, he was entrusted by Visconti to transform the Boboli Gardens of the Palazzo Pitti in Florence into a magical “Persian miniature” Troy for an opulent one-off staging of Troilus and Cressida. In 1951 Visconti employed him again as assistant director, this time on the film Bellissima, starring Magnani.

When Zeffirelli made his debut as a stage director with Carlo Bertolazzi’s Lulù, Visconti mocked his protege’s sign of rebellion. Nevertheless, Zeffirelli was tempted back into what many maliciously called the “Visconti stables” to do the sets for Chekhov’s Three Sisters (1952). He was also called in as assistant director on the film Senso (1954). After being treated roughly on the set by the ever more despotic Visconti, he was relieved to be released before filming ended, since he had been engaged to design the sets at La Scala, Milan, for Rossini’s L’Italiana in Algeri.

His sets so pleased the Scala’s manager, Antonio Ghiringhelli, that he was invited back the next season to design another Rossini opera, La Cenerentola. This time he ended up directing it, too. He now found himself hailed as a promising new opera director. In 1954, Maria Callas appeared at La Scala in Spontini’s La Vestale, directed by Visconti. Zeffirelli’s production of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore was due to open in the same week, and inevitably was treated as less important. But he won Callas’s confidence and succeeded in convincing her that she should try lighter roles. She was delighted to let Zeffirelli direct her in Il Turco in Italia, which was a great success for both of them in 1955.

Thanks to the conductor Tullio Serafin, whom he respected as another of his mentors, Zeffirelli was invited to London in 1959 to direct Lucia di Lammermoor at Covent Garden with the newcomer Joan Sutherland, with whom he was often to work afterwards. Covent Garden then had the brilliant idea of inviting him to direct the double bill of “Cav and Pag” (Cavalleria Rusticana and I Pagliacci). British operagoers were stunned by his realistic staging of the former, and it was this production that convinced Michael Benthall to invite Zeffirelli to the Old Vic to direct an “Italian-style” Romeo and Juliet, starring John Stride and Judi Dench, in 1960. The younger actors of the Old Vic company were at first disconcerted when Zeffirelli instructed them to grow their hair long, but later recognised that it made them feel at home in the piazza of Verona, if not in Waterloo Road.

Kenneth Tynan recognised it as a breakthrough in Shakespearean production. Zeffirelli succeeded in bringing out the genuine Italian feeling in the tragedy, sometimes at the expense of the verse – as many other British critics were quick to note. He was not to be so successful with his next production in Britain, a confusing Othello with John Gielgud at Stratford-upon-Avon. His third Shakespeare production in English came in 1965 with Much Ado About Nothing at the National, which was a hit.

Meanwhile, he had directed Callas in Tosca at Covent Garden and in Norma in Paris. He had also been back to Italy where, in Venice in 1963, he staged Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, one of the last times Italian theatre critics were to give him unanimously good reviews. His Italian version of Romeo and Juliet, first seen in the open-air Roman theatre in Verona in 1964 and then on tour, was even more robust than in London, but again it was to please audiences more than the critics. Back in London, at the Old Vic in 1964, his Hamlet, performed in Italian by the Proclemer-Albertazzi company, was respectfully received.

Zeffirelli’s umbilical-shaped set for Hamlet and the “corridor of the mind” set which he invented for Arthur Miller’s autobiographical play After the Fall, covering up the play’s weakness, were examples of how, as a designer, he was getting close to the visionary concepts of Edward Gordon Craig. Miller went to Naples in December 1965 to see Zeffirelli’s production of his play, and was particularly impressed by the set and the offbeat casting of Monica Vitti in the Marilyn Monroe role. However, Zeffirelli’s war with the Italian critics continued when he refused to invite them to review his 1965 production of Verga’s La Lupa, which gave Magnani a triumphant stage comeback. His greatest theatrical work in the following years was done for the Old Vic, where he staged Eduardo De Filippo’s plays Saturday, Sunday, Monday and Filumena Marturano, both starring Plowright.

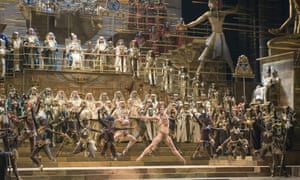

In the US, too, in the 1960s, Zeffirelli thrived with operatic productions. He directed an elegant and evocative version of Verdi’s Falstaff, conducted by Leonard Bernstein, at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1964. Two years later, he directed Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra, which opened the new opera house in Lincoln Center, to which he returned frequently over the following decades.

In 1957 Zeffirelli had directed a rather inconsequential Italian film comedy, Camping. His real debut as a film-maker came 10 years later with The Taming of the Shrew, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. As he wrote in his autobiography: “I had already worked with difficult performers like Callas and Magnani so Liz and Richard didn’t scare me.” Even so he had a lot of problems on the set.

The film was well received, and this prompted Paramount to back his English-language film of Romeo and Juliet (1968), starring the attractive newcomers Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey, photographed by the incomparable Pasqualino de Santis and dressed by Danilo Donati. It was shot on location in various parts of Italy, piecing together an authentic-looking period Verona. The film was a huge box-office hit – especially with young audiences not normally attracted to Shakespeare – and finally solved Zeffirelli’s financial worries, as he had a percentage of the profits.

De Santis and Donati both won Oscars, and Zeffirelli was nominated for best director, but he was unable to attend the ceremony because he had been involved in a car crash when Gina Lollobrigida was driving him to a football match. He suffered severe head injuries and though he was to have facial surgery which more or less restored his appearance, close friends believed that the accident was to blame for his subsequent erratic behaviour.

Certainly it prompted a bout ofreligious zeal, as he believed that a miracle had saved him. He dedicated himself to religious films such as Brother Sun, Sister Moon (1972), about Saint Francis of Assisi, and the very popular TV mini-series Jesus of Nazareth (1977), with Robert Powell, which he considered to be a God-sent mission. He also became the regular metteur en scène of important Vatican events.

His remake of The Champ (1979), starring Ricky Schroder, proved to be a box office hit. It was pure schmaltz, but the young star and a manipulative screenplay ensured its success. He tried for another hit, reworking Romeo and Juliet as Endless Love (1981), but it was only modestly popular, marking his last foray into the youth market.

Zeffirelli then concentrated on a cycle of films of operas. In La Traviata (1982), he made effective use of the flashback device that had not been appreciated at his 1964 Scala production. His 1986 film of Otello was perhaps underrated. However, the Italian musical world would never forgive him for his fanciful film The Young Toscanini (1988).

In 1990, he had a popular success with a concise movie version of Hamlet, with Mel Gibson in the lead role. Gibson made a creditable stab at the character, but it did not have the powerful impact of Zeffirelli’s Italian stage production. At home and abroad, he had always loved to work with the biggest stars. In the 80s, he directed two of the Italian theatre’s most adored leading ladies, Valentina Cortese and Rossella Falk, in Schiller’s Mary Stuart.

In the mid-90s he made his debut at the Arena of Verona with the most sumptuous Carmen ever staged, even in that home of grandiosity, with 28 Spanish dancers in the ballet. The crowds were ecstatic and it has been revived regularly. A “semi-staged” and star-studded one-off production in 2000 at the Rome Opera House marked the centenary of the first performance there of Puccini’s Tosca, with triumphs for Luciano Pavarotti as Mario and Inés Salazar as Tosca. Zeffirelli won unanimous praise for the simplicity of the staging on a central rostrum, with the orchestra seated in a semi-circle around it. For a director sometimes criticised for over-sumptuous productions, it was an example of professional acumen for an event that necessitated economy but also dignified execution.

Having failed to get elected to the city council of Florence in the 1980s, Zeffirelli seized on the chance offered by Silvio Berlusconi to stand for the senate in a safe seat in Sicily in the 1994 general elections. Two years later he was re-elected, and served until 2001.

Berlusconi’s company Medusa then co-produced the film about Callas that Zeffirelli had been wanting to make for many years. Callas Forever (2002), starring Fanny Ardant, was more a homage than a biopic. It was difficult to be convinced by the imaginary story of her sad last months in Paris, where a gay impresario (played by Jeremy Irons, interpreted by some reviewers as a Zeffirelli figure) convinces the star that modern technology would make it possible for her to do a film of Carmen, redubbing her voice from better days.

In 2001, at the pocket-sized Teatro Verdi in Busseto, he staged an exquisitely tasteful production of Aida, an opera that he had always staged so opulently on larger stages. It was revived in 2003 and toured on larger stages, but still in minimalist form, winning praise all round. It made up for his less-appreciated return to another of his warhorses, La Traviata, also in Busseto, staged around a Plexiglas cube. In 2003 he directed Plowright in Absolutely! (Perhaps), from Pirandello’s Così È (Se Vi Pare), at Wyndham’s theatre, London.

His lavish opera sets and designs distinguished his 2006 production of Aida at La Scala, billed by Zeffirelli himself as “the sum of all the others – the Aida of Aidas”, but it was also notable for a gala performance that included a clamorous exit during the first act by Roberto Alagna who, after singing Celeste Aida, had been booed by half of the audience. Throughout his 80s, Zeffirelli’s operatic productions continued to be staged at the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome and the Arena in Verona.

In 2004, he received an honorary knighthood from Britain, having two years earlier finally received the lifetime achievement prize at the David di Donatello awards (the Italian Oscars). It was his first really significant accolade from the Italian cinema world, which he felt had never recognised him as an “auteur”. It was a pity, because outside the social whirl, Zeffirelli had endearing personal charisma and generosity, and he was gifted with a creative flair in the tradition of the great Renaissance craftsmen. In 2013 he was given Florence’s highest honour, the Fiorino d’Oro, or golden florin, and bequeathed his archives to the city.

He is survived by the adult sons he adopted in 2000, Pippo and Luciano.

• Gianfranco Corsi Zeffirelli, opera, theatre and film director, born 12 February 1923; died 15 June 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment