|

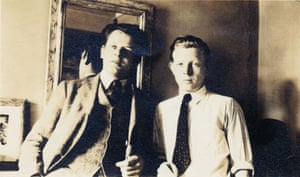

| Patron and painter … Peggy Guggenheim and Jackson Pollock in front of Mural in 1943. Photograph: George Kargar/Peggy Guggenheim Collection |

Jackson Pollock, the one-man tornado who spattered his way to fame

In the 1940s, the poor alcoholic artist was saved by a rich heiress, Peggy Guggenheim. Now the pair are reunited in a knockout Venice show that busts all the myths about America’s noblest savage

Jonathan Jones

Friday 24 April 2015

I

n a black-and-white photograph taken in about 1946, they pose together awkwardly before a vast, swirling, abstract painting. She clutches pampered little dogs in each arm. He wears a suit, for once, as he looks at Peggy’s pooches with a shadowed face.

Peggy Guggenheim and Jackson Pollock were not lovers. They were not even friends. But the encounter between these two very different people changed art.

At the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, at the grandest end of Venice’s Grand Canal, where Guggenheim settled in the late 1940s and which is today a museum of her compelling art collection, that encounter has just been recreated. Earlier this week, a barge made its way up the Grand Canal carrying a very large and very precious cargo. Boxed up and bouncing on the waves came Jackson Pollock’s painting Mural – the canvas in that photograph. More than 6m wide and almost 2.5m tall, this epic canvas is the painting that made Pollock into Pollock and gave birth to the art of our time. At last, it has been reunited with the spirit of the woman whose bold passion for art brought it into being, as part of a remarkable exploration by the Peggy Guggenheim Collection of Pollock’s legend and achievement.

Mural is an explosive meeting of worlds, of cultured sensibility and raw energy.

|

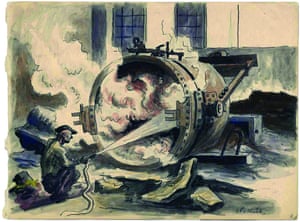

| Jackson Pollock’s masterpiece Mural, 1943, oil and casein on canvas. Photograph: University of Iowa Museum of Art |

At the start of the second world war, Guggenheim, a member of one of New York’s wealthiest families, whose sheltered childhood had been emotionally shattered when her father died on the Titanic, went on a spending spree, buying modern art from artists who were desperately planning their escapes from the Nazis. She set sail from Nazi-occupied France in 1941 with a surreal cargo. Literally. She not only took crates full of surrealist art but an actual surrealist, Max Ernst, whom she saved from the Gestapo and married, only to separate from him in 1943.

Pollock was a desperate, failing artist struggling to survive in New York. He had been declared medically unfit to serve in the war as a result of alcohol dependence and depression. The artist started drinking as a teenager in Los Angeles. He came from a rural family so poor and rootless that even their name was not their own – his father was given away, perhaps even sold, as a child to a farming couple called the Pollocks, who used him practically as a slave. Oddly, the Pollock sons – starting with the eldest, Charles, whom his kid brothers, including Jackson, emulated – all wanted to be artists.

A drawing by Charles on show at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection portrays Jackson in 1935 wearing jeans and waistcoat and playing a banjo. He looks like a character from a John Steinbeck novel or a bluegrass singer – a son of the Great Depression, playing sad songs of America. Pollock’s early paintings, shown here alongside Charles’s far more realistic and far less original works, are like illustrations to strange country ballads. His intense little painting Going West (c1934-35) is a hypnotic vortex of gothic Americana. A ghostly wagon train heads through the desert under a spectral moon. The first myth this exhibition’s new look at Pollock knocks down is the notion that he had no natural talent: his early works glow beside his brother’s studious efforts. His weird American genius is already exploring some lost highway all its own.

When it comes to the imposing Mural, more myths tumble. When Peggy Guggenheim first looked at a painting Pollock submitted to Art of This Century, the gallery she opened in 1940s New York, she sneered. Her adviser, Piet Mondrian, made her look again. She not only gave Pollock a one-man show at her gallery – which he filled with the mythic women he was then painting in imitation of his heroes Picasso and Miró – but commissioned him to paint a mural for her townhouse at 155 East 61st Street, New York.

Mural is in every textbook history of modern art as a heroic turning point, but it has been difficult to respond to it as a work of art. Guggenheim gave it to the University of Iowa in 1951 and it is rarely seen elsewhere. Moreover, it was dirty, varnished and the worse for wear.

The Mural that has come to Venice ahead of this summer’s biennale is a masterpiece reborn. It has been immaculately cleaned and restored at the Getty Conservation Institute. The result is a scintillating starburst of vitality, a tornado of reds, yellows, blue-greys and browns that roll and twist across the widescreen canvas like a prairie storm, sweeping up cattle, people, and all previous notions of art in its path.

Pollock’s widow, the artist Lee Krasner, recalled that he stared at the long white canvas on which he was going to paint Mural for weeks, paralysed with anxiety, before suddenly painting the whole thing in a single night. She was romanticising. The restorers have discovered layers of work that prove Pollock worked on the piece for weeks or months.

Another legend is that it wouldn’t fit into Guggenheim’s hall, and so her friend Marcel Duchamp cut it down. Again, this is not true – the restorers found no evidence of such an alteration.

The only story their examination cannot disprove (you either believe the anecdote or don’t) is the most dramatic. After installing Mural in Peggy Guggenheim’s house, Pollock is said to have walked over to her fireplace while a polite party was going on, and urinated into the hearth.

If that crazed gesture – some say he was naked at the time – really happened, it was of a piece with the raging abandon of Mural.

People had painted abstractions before, in Europe, but the art of Kandinsky or Mondrian seems almost staid compared with the wild release of Mural. On the cleaned painting, lurid splashes of bright paint are spattered over the canvas’s swarming serpentine shapes. Pollock’s revolutionary idea of throwing or pouring paint starts here. So does his mind-expanding sense of scale. Mural is not a work to be looked at – an “easel painting”, as Pollock’s critical champion Clement Greenberg dismissively called all the polite little European pictures it rendered obsolete – but to be embraced by. It pulls you in, absorbs you. It is bigger than you and it has no end – the forms would swirl on for ever if the canvas was expanded infinitely. It is a landscape to inhabit, a place to be.

It is also a person. It is Pollock. He releases himself into this painting, and to stand in front of it is to feel a connection. Soul speaks to soul. Pollock was never happy, said Krasner, and this time she was surely telling the truth. He was a very lonely man, ultimately unable to communicate even with Krasner, numbing himself with alchohol until he died in a stupid, unnecessary car crash in 1956. But in Mural and the great expansive paintings that followed, he found a way to break out of his solitude and connect with others, to glorify life with improvisations that are the painterly equivalents of saxophone or guitar solos. American freedom and American tragedy dance a desperate duo in his story.

The paintings are so fragile now. The Peggy Guggenheim Collection has also restored Alchemy, its 1947 Pollock masterpiece that was recently cleaned at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, where they are more used to repairing Raphaels. It has been deemed so frail that it will never leave Venice. The endlessly fascinating curls and wisps of paint on its surface look so delicate.

Art of This Century has become Art of That Century. Pollock painted Mural 72 years ago. Yet it contains the art of today within it: installation and performance, and the sense that art can be anything, absolutely anything, are more eloquently embodied in Pollock’s liberating vision than in any number of dry remarks Duchamp once made to some fawning interviewer.

In a vitrine at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, you can see the sticks Pollock used for pouring paint in great astral arcs. So crude, so magical.

Guggenheim was a very civilised person, as her palace attests. But her greatest moment was when she sponsored the genius of America’s noblest savage.

Jackson Pollock / Jack the Dripper Returns

Jackson Pollock / Quotes

Jackson Pollock / A Compliment

Jackson Pollock / Works

Why Jackson Pollock gave up painting

Jackson Pollock / The one-man tornado who spattered his way to fame

No comments:

Post a Comment