|

| Gabriel García Márquez |

Gabriel García Márquez: 'He made no claim for his divinity'

Novelist Mona Simpson reflects on a legacy that extends far beyond 'magical realism'

Mona Simpson

Sat 26 April 2014

I

n one of Gabriel García Márquez's early imperishable stories, a man whose baby has a fever goes out into a rainstorm to throw crabs from the house into the sea; he and his wife think their stench may be causing the baby's illness. On the way back, he discovers an old man in his courtyard. The old man has enormous wings, like a buzzard's, "dirty and half-plucked" and spattered with mud. He speaks a dialect the man and his wife don't understand – they assume he's a sailor from a shipwreck, until a neighbour tells them that he's an angel, who had come to take their baby but stumbled and fell in the mud. They don't kill him, as the neighbour recommends, but they lock him in the chicken coop.

|

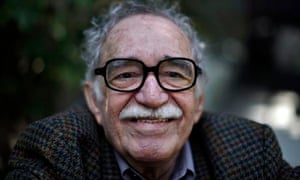

| García Márquez in 1983. Photograph by Paco Junquera |

When their baby wakes up one morning without a fever and hungry again, they decide to set him on a raft with provisions, out to sea. But when they go to release him they find he's become an attraction for neighbours, who toss scraps of food into his cage. The village priest comes to assess the angel's authenticity. He enters the cage and tries to speak to the winged old man in Latin. The old man doesn't understand and his smell is all too terrestrial. Parasites line his wings. He looks more like "a huge decrepit hen", the priest thinks, "nothing about him measured up to the proud dignity of angels." The priest suspects the angel is an imposter and warns the excited villagers that if the presence of wings could prove divinity, hawks and aeroplanes would also qualify. He promises to write to the Bishop, who in turn will write to his superior, and so on, until the Supreme Pontiff gives a verdict in the matter.

Then the story goes circus, and we see the influence of Kafka's "A Hunger Artist". Pilgrims from all over the earth come to see the angel, especially those with strange ailments, and the man and woman who found him begin to charge admission. Then comes this beautiful, prophetic line. "The angel was the only one who took no part in his own act."

The winged old man is besieged; admirers pluck his feathers to rub on their wounds. But the miracles attributed to him come out cross-circuited; a leper who had hoped to be cured sprouts sunflowers from his sores; a paralytic remains paralysed but almost wins the lottery. The town's attention drifts away when another travelling show arrives: a woman who once disobeyed her parents and was turned into a tarantula with a human head. By then, though, the couple have become rich. They build a mansion "with balconies and gardens and high netting so that crabs wouldn't get in during the winter, and with iron bars on the windows so that angels wouldn't get in". They barricade themselves against their bad luck returning. The wife buys satin shoes and silk dresses. The child who had once had a fever grows up playing with the angel as with a dog. "His only supernatural virtue seemed to be patience."

Both the boy and his pet contract chicken pox and when the doctor checks the angel, "there's so much whistling in his heart … that it seemed impossible for him to be alive. What surprised him most, however, was the logic of his wings. They seemed so natural on that completely human organism that he couldn't understand why other men didn't have them too." The doctor's musing could be quoted as his author's aesthetic philosophy.

Time passes. The boy goes to school and the chicken coop collapses (now they're rich the family presumably no longer keeps chickens) and the winged old man seems to be everywhere in the house. "The angel went dragging himself about here and there like a stray dying man. They would drive him out of the bedroom with a broom and a moment later find him in the kitchen … He could scarcely eat and his antiquarian eyes had also become so foggy that he went about bumping into posts. All he had left were the bare cannulae of his last feathers."

Reading "A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings" again, there's a purity to this 1955 story. In the eight pages (in my battered edition of the Collected Stories) there's only one tiny break in tone (the maiden-head on the tarantula) but I suspect that that's because the image has been appropriated by Pixar. We think we see the shape of the story: the very old man is, in fact, mortal after all, like Nabokov's Nina in "Spring in Fialta". We expect to see him die. But no. After a terrible winter, new feathers begin to grow. The woman, in the kitchen cutting onions, watches the ancient angel clumsily try to teach himself to fly again. He succeeds, and as she watches him gain altitude and fly over the last of the rooftops and disappear into the sky, it feels to her like her victory and to us like all of ours.

Much has been said about García Márquez's magic, less has been claimed for his realism, even less of his Christianity. But his aesthetic partners in what came to be called, crudely, "magical realism", Julio Cortázar and Jorge Luis Borges, were profoundly urban and European (each of them grew up partly in northern Europe). García Márquez came to urban Continentalism late, with the exuberance of a boy from the provinces in the clean, stylish capital. He retained the wonderment of a provincial discovering the sophisticated world and the faith in the universe's connected intentionality. He had the gift and the privilege of being sincere.

The story of García Márquez's life and career is as beautifully shaped and fabular as one of his own stories. Born in 1927 in the small town of Aracataca, Colombia, he was raised there by his grandparents for eight years. Aracataca was a "Wild West boom town" and his grandparents' house was full of people – "his grandparents, aunts, transient guests, servants, Indians". García Márquez based his fictional homeland on Aracataca and named it Macondo – after a dusty sign he once passed on a train in rural Colombia. The sign heralded no visible town.

His grandfather was a colonel and a liberal veteran of the thousand days war, who refused to remain silent about the banana massacres that took place the year García Márquez was born. As in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the colonel taught the young García Márquez lessons from the dictionary, took him to the circus every year and introduced him to the miracle of ice, which he first witnessed at the American Fruit Company. The fact that the US was – for García Márquez and his grandfather – the enemy added to the experience. His ideology was shaped by his grandfather, who told him, "You can't imagine how much a dead man weighs", a line that worked its way into the fiction. "Instead of telling me fairytales," García Márquez said, "he would regale me with horrifying accounts of the last civil war that free-thinkers and anti-clerics waged against the conservative government". If García Márquez (known affectionately as "Gabo" in Latin America) gleaned his politics through his grandfather, his grandmother bequeathed him his aesthetic stance. She "treated the extraordinary as something perfectly natural". The household was full of ghost stories, premonitions, omens, portents, superstitions, and magic (all of which could function as a working description of Catholicism). His grandfather ignored his wife's supernatural views, and she relayed them in a deadpan style.

His grandfather died when he was eight and García Márquez rejoined his parents and younger siblings. His father was a struggling pharmacist (a "quack doctor," according to some) and the family moved frequently. Gabo was an excellent student but an insecure child. A friend recalled him as a skinny boy, "circumspect, almost a bit sad, and in any case lonely and unknown".

He moved to Bogotá to study law but quit to become a journalist in Barranquilla, where he read William Faulkner and Virginia Woolf. He was a film critic for a newspaper for a year, then, at 30, he took a position at a newspaper in Caracas and helped in the 1958 Venezuelan coup d'etat, leading to the exile of president Marcos Pérez Jiménez. That same year, he married Mercedes, to whom he remained married until his death last week. His first published book was a journalistic account of a shipwrecked sailor from a Colombian naval vessel carrying contraband goods. The controversy following an expose of official accounts landed him a post as a foreign correspondent and finally got him to Europe. In 1961, the García Márquez family travelled by Greyhound bus throughout the southern US; García Márquez had always wanted to see the south to pay homage to Faulkner's country.

Gabo's aesthetic development was gradual, and then sudden. The story goes that he was driving his family on holiday when the first line of One Hundred Years of Solitude came to him ("Many years later as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.") He turned the car around, returned home and wrote feverishly every day for 18 months, as if taking dictation. During that time, Mercedes pawned her jewellery (which the discriminating pawnbroker pronounced to be coloured glass) sold the car and, according to some accounts, the toaster. They owed money to the butcher, the baker and a kind landlord. But still Gabo and Mercedes didn't have enough postage to send the entire manuscript to the publishers, so they sent only the first half. Fortunately, the book's appeal was undeniable, leading the novelist William Kennedy to deem it "the first piece of literature since the book of Genesis that should be required reading for all of humanity".

Certainly, it's a beautiful novel that many writers of my generation remember the experience of reading the way they remember other cultural events of their lifetimes; the assassination of John F Kennedy or Martin Luther King. I remember where I was the year I lived in its trance. It was 1980 – the book had been out in English a decade before I discovered it. Under the spell of its plausible flying carpets and avalanches of butterflies, I spent the summer in a sublet cottage in the Berkeley Flats, where a serial rapist continued his attacks, unapprehended. I was writing a novel set on a coastal cliff in the northwest, where armless thalidomide children wore small tuxedos, serving adults in the restaurant. There was also a road scene through miles of cornfields, where living children worked as scarecrows.

There are few modern works of genius that feel as unlaboured as One Hundred Years of Solitude. And yet, in his Paris Review interview, Gabo says, "Ultimately, literature is nothing but carpentry. Both are very hard work. Writing something is almost as hard as making a table. With both you are working with reality, a material just as hard as wood. Both are full of tricks and techniques. Basically very little magic and a lot of hard work are involved."

The interview was conducted in 1982. No doubt, after the gift and cataclysm of One Hundred Years of Solitude, which vaulted Gabo and Mercedes, like the couple in the angel story, from intellectual poverty to riches, international literary respect and household fame, the dictation became fainter and harder to hear. Or perhaps that kind of gift only happens once. He was apparently so overwhelmed by attention that at one party he put up a sign saying "Forbidden to speak of One Hundred Years of Solitude."

No worries. García Márquez worked on. If none of the other books have the magic "dictated" quality of One Hundred Years, they're great, deep books, in their own way. Love in the Time of Cholera, which chronicles García Márquez's parents' romance, was a huge bestseller. When he died, Gabo left us seven novels, 10 non-fiction works, and, as significant as the epic narratives, a thick collection of novellas and (not yet aggregated in English) stories. A beautiful shelf of books. Carlos Fuentes called him "the most popular and perhaps the best writer in Spanish since Cervantes".

One reason we all want to claim García Márquez's created world is that he made so few claims of ownership on his books himself. He famously said that Gregory Rabassa's translation into English of One Hundred Years of Solitude improved on the original. Like his "very old man with enormous wings" García Márquez seemed, to his readers, miraculously modest, and made no claims for his divinity. He seemed to do everything possible to deflect elevation. He stressed the naturalistic nature of his realism. His Nobel address begins with a couple of paragraphs of Latin American events that sound as if he'd made them up:

Antonio Pigafetta, a Florentine navigator who went with Magellan on the first voyage around the world, wrote, upon his passage through our southern lands of America, a strictly accurate account that nonetheless resembles a venture into fantasy. In it he recorded that he had seen hogs with navels on their haunches, clawless birds whose hens laid eggs on the backs of their mates, and others still, resembling tongueless pelicans, with beaks like spoons. He wrote of having seen a misbegotten creature with the head and ears of a mule, a camel's body, the legs of a deer and the whinny of a horse. He described how the first native encountered in Patagonia was confronted with a mirror, whereupon that impassioned giant lost his senses to the terror of his own image.This short and fascinating book, which even then contained the seeds of our present-day novels [How many writers would have kept this source to themselves, exaggerating their own powers of invention!] is by no means the most staggering account of our reality in that age.

To make sure everyone got the point, he said it outright:

I dare to think that it is this outsized reality, and not just its literary expression, that has deserved the attention of the Swedish Academy of Letters. A reality not of paper, but one that lives within us and determines each instant of our countless daily deaths, and that nourishes a source of insatiable creativity, full of sorrow and beauty, of which this roving and nostalgic Colombian is but one cipher more, singled out by fortune. Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable.

García Márquez said, again and again, that his triumph is ours no less than his. And amidst the carnage, the savagery, the corruption and the solitude of his century in Latin America, his work claims again and again, "There is always something left to love."

Groups of guards shooting Milky destroys the hammer contained the stone of strength: in Guardians of the Galaxy, when Super evil the his Accuser Ronan had to hammer the stones intend to use the power to destroy the entire planet Nova, Star-Lord suddenly dancing led him to be distracted. watch happy death day online

ReplyDeleteDRAX the Destroyer and armed Rockets crushed the Ronan's hammer with ease, making the power stone shoot out. watch rampage full movie online free The guard and hold hands, control the power of the rock strength, destroy Ronan. Why a stone infinity can destroy an entire planet not plagued one mediocre?

Space rocks remote control: in the Avengers (2012), SHIELD block research Tesseract contains space rocks to create weapons of mass destruction. But do not understand how the evil God Loki, though not possessing the stone space but still made it to open the doors of the universe to him reached the base of the SHIELD. the devil's candy review

The confusing thing than a killer like Hawkeye can explain the mechanism of action of block Tesseract though not as physical as expert Dr. Erik Selvig. watch Avengers Infinity War online free hd

Kaecilius escape from the effects of Ice time: in Doctor Strange (2016), witch Kaecilius and they attacked the main Hong Kong, paving the way to the demon Dormammu attacked Earth. happy death day nude However Stephen Strange used the eye of Agamotto treasures, containing Ice time, reverse time to prevent the attack.