|

| Fidel Castro talking to Gabriel García Márquez in Havana in 2007. |

Fidel Castro worked on Gabriel García Márquez's manuscripts

The Nobel laureate sent the Cuban dictator all of his books and received his factual and grammatical notes before submitting them to his publisher

Danuta Kean

Tue

Feted as a revolutionary hero and demonised as an enemy of the free world, Fidel Castro also played an unexpected role in global literature. The Cuban president, who died on 25 November, acted as unofficial copy editor for the acclaimed novelist Gabriel García Márquez, providing line-by-line corrections for the writer after the two struck up a close friendship in the late 1970s.

Dr Stéphanie Panichelli-Batalla, lecturer in Latin American studies at Aston University, told the Guardian: “The president was an avid reader. When they met in 1977, they had several conversations about literature and eventually Fidel offered to read his manuscripts, because he had a good eye for detail.”

The Colombian Nobel laureate, who died in 2014, was a supporter of the Cuban revolution, support he never relinquished despite Castro’s record of human rights abuses. Panichelli-Batalla, who co-authored a book about their relationship titled Fidel & Gabo in 2009, said the writer would send completed manuscripts to Havana before submitting them to his publisher.

|

| Fidel Castro |

Castro’s corrections were factual and grammatical rather than ideological, she added. “After reading his book The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor, Fidel had told Gabo there was a mistake in the calculation of the speed of the boat. This led Gabo to ask him to read his manuscripts … Another example of a correction he made later on was in Chronicle of a Death Foretold, where Fidel pointed out an error in the specifications of a hunting rifle.” Elsewhere, Castro offered advice about the compatibility of bullets with guns used by García Márquez’s characters.

The two met in a Cuban hotel in 1977. Though the meeting has been described as coincidental, Panichelli-Batalla said Castro may have orchestrated it after he heard the Colombian writer was working on a nonfiction book about life in Cubaunder the US embargo, using testimonies from ordinary Cubans. The book never appeared.

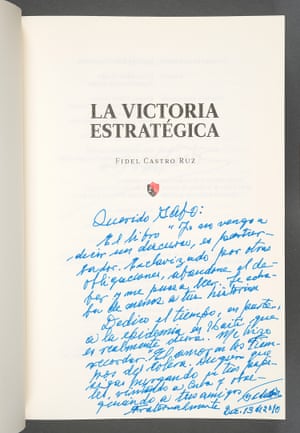

A sign of the closeness of the two men is revealed in a book among García Márquez’s personal library acquired by the Harry Ransom Centre at the University of Texas this week. A note to García Márquez written by Castro in the front of La Victoria Estratégica is addressed to Gabo, the affectionate nickname used by South Americans for the writer. Castro wrote the note in 2010, taking time out from work alleviating the devastation of the Haiti earthquake. “Your book Yo No Vengo a Decir un Discurso [I’m Not Here to Give a Speech] is disturbing,” he sold his friend. “Enslaved by other obligations, I abandoned my duty and started reading. I missed your stories.” The plague in Haiti, he added, “reminded me of Love in a Time of Cholera”.

García Márquez inspired more than one global leader, as shown by the range of books acquired by the Harry Ransom Centre. A Spanish copy of Bill Clinton’s memoir My Life is inscribed: “To my friend Gabriel García Márquez, with thanks for your life, your inspiration and your kindness.” The novelist is known to have discussed Cuba with the former US president and Dr Panichelli-Batalla said a number of dissidents were released as a result of his intervention.

Although García Márquez accepted editorial advice from Castro, it is not known whether he attempted a similar service in return. In an 1978 interview, he said that he would criticise the Cuban president to his face in private but never in public.

Anna Hervé, a publishing editorial manager, said the success of García Márquez and Castro’s collaboration was rare. “Most great artists define themselves in opposition to the elite in the modern era. And dictators have notoriously poor taste, as a rule.”

No comments:

Post a Comment