Befriending the Imprisoned Christ

|

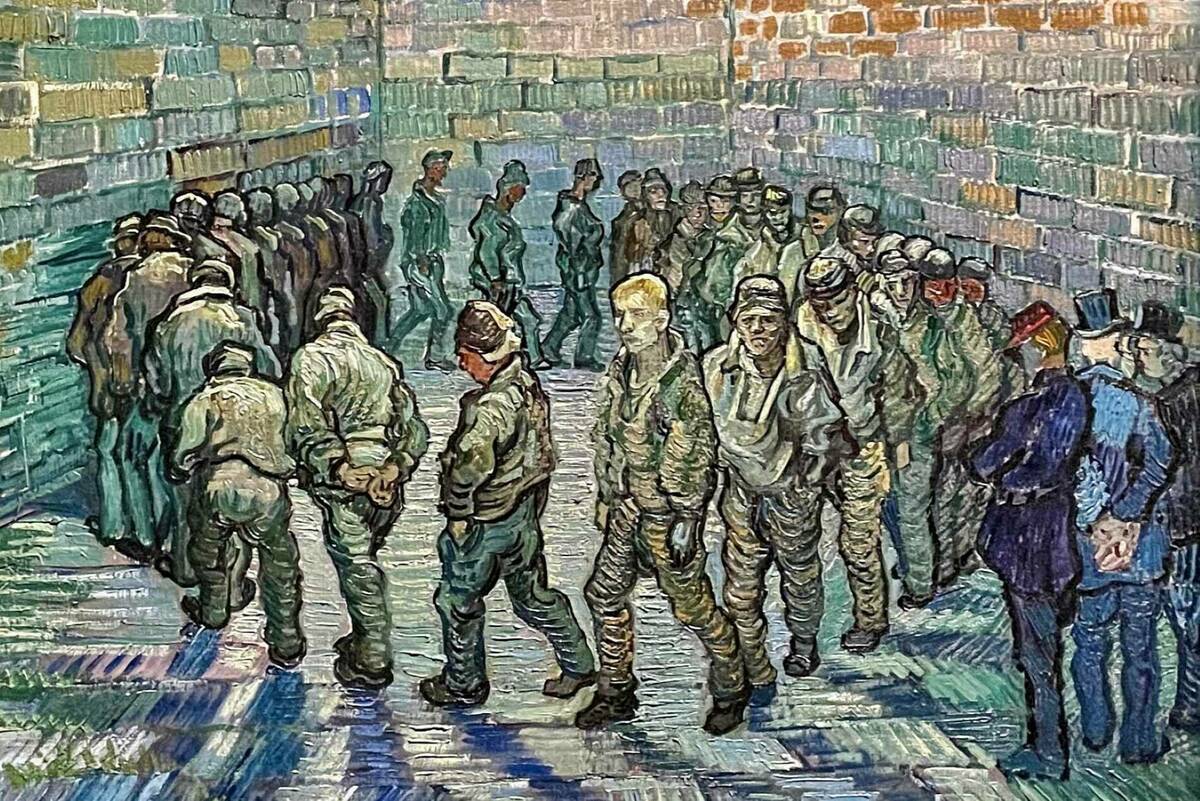

When my wife and I lived in Leavenworth, Kansas in the nineties, we had the great privilege to work in the prisons there. Leavenworth is a prison town, as is its abutting neighbor, Lansing. In Leavenworth one finds two federal civilian prisons, the historic “Big House” (so named for the domed central building that connects the blocks, oddly reminiscent of the U.S. Capitol) and what is interestingly called a “prison camp.” There are also two military prisons, the United States Disciplinary Barracks (USDB), the only maximum-security prison for the military, and a regional medium-security. To add to this penitential cornucopia, Lansing has a full complement of state prisons and gender-specific privately run prisons. Leavenworth and Lansing are nice enough towns, but an outsized number of their denizens are criminals, convicted and otherwise.

Our connection to the prisons came through my employer at the time, St. Mary College (now University of St. Mary), a very small Catholic college sponsored by the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth. St. Mary had offered degree programs for prisoners when they could still qualify for Pell Grants. By the time we had gotten there, however, the source of federal funds had been cut off and so had the college’s official relationship with the prisons. The logic of this (to my mind short-sighted) decision, is that it was unbecoming for prison guards to be working overtime to send their children to college while the convicts they were guarding received their education for free.

Unaffected by the change of policy, a faculty member by the name George Stieger continued a Catholic ministry he and his wife had established—a weekly Bible study in the state prisons. There was also an elderly nun still playing organ for Mass at the Big House. We soon joined the ministry to the state prison. A possibility opened up in the federal system as well. Right before our arrival there had been a prison riot in the Big House, which proved too much for the beautifully souled Sister Anne. She described hardened prisoners weeping in panic at the realization that their fellow inmates now ruled the halls. Understandably, she was relieved to hear that my wife, Sandra, was an organist and was willing to replace her. It was a paid position. Since I had had a lifetime of committing liturgical crimes with my guitar, we together did two masses a week, one in the Big House and the other at the camp.

For those wondering, a federal camp is a place for minimum-security prisoners, that is, mostly white-collar guys. Indeed, one Sunday morning when the bishop had accompanied us, he espied a recent big-league donor as we were heading in. That said, although it does in fact have a tennis court, and I actually overheard two inmates complaining that the court needed to be resurfaced and the net tightened, one should be under no delusion regarding the nature of even the lowest level prison. One’s placement within the prison hierarchy is a not a function of the crimes one committed but of whatever crimes the government was able to establish. As one of the guys told us, just because you were convicted for a lesser crime does not mean you are a lesser criminal.

I can still recall first entering the Big House. We sat in a room along with parents, wives, and friends waiting to visit their child, their husband, or friend. Over time, I could tell who was visiting for the first time, profound sadness and anxiety distorting their faces, their voices marked by uncertainty. That would wear off in time. For us it was not sadness but apprehension and even panic when it was revealed that I had forgotten that there was in my guitar case a rather large hunting knife my father had given me for some odd reason. Upon finally opening that little compartment used to store picks, capos, and strings, the guard said solemnly, “Sir, is there a reason you are bringing a knife into a maximum-security prison?” To be fair, it was a very good question. Fortunately, he could discern the difference between an idiot and a conspirator, but he kept the knife. He also instructed me to keep a close watch on my extra strings since they were very handy in the creation of prison tattoos.

Before long we were walking through the gate, which shut with a closing clang worthy of a movie, and heading to the chapel. Oddly, we could only get to the chapel by walking through a pitch-black movie theater filled with four hundred or so lifers. Even after making that passage every Sunday for two years, it never felt safe at all. The chapel, however, was a very different thing. Although brutally nonsectarian, the chapel was a place of refuge from the rest of the prison and the men who came to it insisted that it remain that way. Of the two Sunday services, the Catholics went first, the much larger Protestant service afterward. Our community was a fantabulous grouping of Italian mafiosi, Mexican gangsters (the two large gangs took turns on which Sunday they would attend—thank God), and some well-known bank robbers (one of our lectors was a leader of the Stop Watch Gang).

Our work in the state prisons was different. We helped lead Bible studies in the maximum and minimum Lansing prisons. While the federal prisoners were mostly guilty of financial and racketeering crimes (which meant because of the Ricco Act lots of mafia and gang members), the men we got to know in the state prisons had committed more quotidian offenses such as murder, child rape, drug-dealing and so on. We met some very clever people in the federal system, who had had worldly success before their fall, but in the state system we met folks who had always been down on their luck.

Dostoevsky, in his prison novel, Notes from a Dead House, describes how Russians consider some crimes as a “misfortunes” and look upon their perpetrators “with pity.” That well captures how I saw many of the men we met. They had come from rough circumstances and through their crimes had made things even rougher for themselves and most painfully for their children. The saddest conversations were with men who had recently learned that their sons were now criminals. It is one thing to ruin one’s own life by the punishment of prison but to watch helplessly as your child hurls towards the same fate is a much greater affliction, perhaps the greatest a prison can offer.

The men we came to know were guilty of terrible deeds; they deserved to be in prison and I was, on the whole, glad they were. That sounds terrible to say, and you might think me a terrible person for saying much less thinking it. Yet that is how it appeared to me and I never pretended otherwise. It might sound non- or pre-Christian—did not Christ tell us that he is found in the prisoner? He did and he is, but not because the prisoner is innocent of his crime.

Rather, we best enter into this mysterious identification by viewing prison as a place of moral clarity with the guilty properly punished. I am speaking of what is mostly the case. There are, of course, the unjustly imprisoned. One must also acknowledge the very serious evils involved in the way we incarcerate, from the treatment of prisoners and, as Pope Francis has recently stressed in connection to his condemnation of the death penalty, to the ease with which we hand out life sentences. Such injustices do not, however, cancel out the fact that there are also real crimes, real victims, and that justice is done when criminals are deprived of their freedom and their potential victims remain just that—potential victims.

Prisons, therefore, are places of justice. Justice reigns inside those walls. That is their glory. The same cannot, however, be said of the cities just beyond those high concrete barriers festooned with razor wire. Within the walls, those who had done evil are getting their just deserts, but outside of them unpaid debts for evil deeds abound among the free. I am not saying, of course, that the people not in prison have committed the same crimes as those inside. Such a statement would be morally obtuse and a pathetic exercise in virtue-signaling. I am saying, however, that the men within those walls are paying for the wrongs they have done, but we are not, at least not clearly so. Thus, we should consider those in prison as just in a way we are not. In that sense, prisoners enjoy a certain moral privilege over the unincarcerated.

I say all of this in order to better understand Jesus’s insistence that we visit those in prison and that by visiting them we are visiting him. Jesus is quite insistent about it, one might even say pushy (Matt 25:31-46). Such is the truth of the matter that Jesus asserts that whenever one visits a prisoner, he is being visited even if the visitor has no such thought in his or her mind. They ask confusedly: “When did we ever visit you?” Moreover, the simple act of visiting prisoners is determinative of one’s final destiny. Those who take the time to visit will hear at the final judgment the wonderful invitation, “Come, you blessed by my Father, inherit the Kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the cosmos,” while those who ignore the imprisoned will hear, “Go from me, you execrable ones, into the fire of the Age prepared for the Slanderer and his angels.” Notice that Jesus does not say that one must help the prisoner to escape or campaign on Twitter for his or her release or to join a political movement to end to all incarceration. No, the command is simply to visit. In other words, to go to the prison, sit down with someone, and there exchange some kind words.

Every Sunday when we went into the camp, I always marveled at the various ways that visitor and visited interacted. Rarely was there a lot of talking—I gathered most everything had already been said or that what remained was too painful to say. Mostly, they simply shared time together, sometimes playing chess or, more often, checkers, and looking over pictures. There was little joy, but there was a level of contentment that a needed task was being done, a bond maintained.

I take “to visit” to mean “to befriend,” even if only for the duration of a visit. It is an intentional act, that is, a decision of the will, a determination of the means, and the completion of the action. Indeed, the system prevents random people from just showing up. Rather both sides must be deliberate about it. Visitors must know who they are visiting and must receive permission from that person and put on a list. Lawyers and advocates might be on the list, but they are not what is meant by the term “visitor.” A visitor is someone who comes from outside the system to talk with the prisoner about what is outside.

Indeed, the greatest gift a visitor can bring is a connection to what is not the prison or the tangled legal system whose rules and personalities consume so much of the average prisoner’s mental and emotional energy. Indeed, the visitor is him- or herself freedom from such things, their bright clothing contrasted with prison drab, the women wear makeup, and the men have fancy glasses and watches. Every bit of it bespeaks: not prison. There are the manipulators, of course, those who will seek to use their visitors to get something from the outside and will walk away as soon as they prove useless. For the most part, the visitor does his or her part by simply showing up.

Of course, we came in as ministers of the Gospel of Jesus Christ and to be friends in Christ. I put it that way not to make what we were doing sound grandiose but because that is precisely what most of those we visited wanted from us. There were, of course, what can be called “professional prisoners” who were sorry they had been caught (or more likely railroaded—one quickly learns that every prisoner is innocent of precisely that crime of which they were convicted!), but these men evinced no remorse or repentance. This was common with the mafia and gang members. Serving time was part of the job.

The main issue was whether their families were being taken care of by the company while they were away on an extended business trip. They were, on the whole, very happy to befriend us, but beyond a bit of the outside world, we had little to offer them. But there were others who were grievously sorry for what they had done. There was one young man who had planted a bomb in a theater of African-Americans watching Spike Lee’s Malcom X. You would have heard of it if that bomb had gone off, but it did not. He, however, was given, like many young men we encountered, a “hard forty,” meaning four decades without the possibility of parole. While in prison he had taken the extraordinarily risky step of leaving the Aryan Brotherhood. He had scrubbed his fearsome tattooed teardrops raw but visible they remained. Leaving the Brotherhood is normally a death sentence (“blood in, blood out”) but, given the nature of his crime, he was also a target of the Black gangs. One of the guards told us that they had taken bets on how long he would survive.

Through it all he had become a great admirer of Hans Urs von Balthasar. The first time I met him he asked me to bring him The Balthasar Reader. I did. I regret that I never asked him why he was so attracted to Balthasar. But, if I had to guess the reason, it would be the Swiss theologian’s emphasis on God’s gracious “yes” to his broken creation. Grace, it seems, requires justice to be appreciated. For those of us who have escaped the justice we deserve, grace loses its savor, most likely sliding into its opposite. We forgot that if we are saved by grace, we are being saved from justice. We are getting a good thing we do not deserve in place of the bad thing justice demands. In that sense, prison is fertile soul for the Gospel authentically preached.

Perhaps I can make this point another way. There was another man, let us call him Anthony. Anthony was in prison for killing two police officers during a bank robbery. Curious how this mild-mannered man could have prevailed in what must have been a fierce battle, I asked the retired army officer who led our group. He replied that Anthony had seen action in Vietnam and that while he “had seen the elephant,” they had not. Anthony came to our Bible study and whatever we studied he always had the same question: Can God forgive someone like me? What a great privilege to be able to simply and clearly convey the good news of what God has accomplished in Christ to a person who had grown wise enough to fear God’s justice. Although we were called upon to confirm the depth of God’s grace to Anthony, he in turn performed the much more arduous task of revealing to us what God’s promise must actually mean if true.

Anthony’s life had been changed by that Good News. Evidence of this is that he was one of the few who would tolerate child rapists in the group. In prison, those who harm children are “the very least of these.” Once when a visiting priest challenged the men assembled for morning Mass to extend love to the child rapist, the murmurs became so menacing that he wisely stayed on the altar during the sign of peace. As my wife and I were making our way through the men, one grabbed me to say that they do love them . . . by not killing them. One consequence of this is that whenever someone showed up for Bible study who had been convicted of harming a child, everyone else left. All except Anthony. He continued to come even when he was the only non-child rapist left.

Yet, grace is fragilely received. One week, Anthony entered with a crumpled letter in his leathery hands the shabby and cramped room where we had our study. (The prison chaplains were invariably Southern Baptists who had zero use for Catholics—even the Odin Reading group got a better room.) He had gotten a final letter from his pen pal of many years. It is a weird fact of prison life that many men have epistolary relationships with women they have never met. Anthony had been writing back and forth with a woman for many years and their relationship had gotten to the point that she felt free to ask what he had done that had landed him in prison. She was a professed Christian who presumably knew that God deals with us not in justice but graciously. So, he told her.

The letter he received back was as devastating as it was revealing of the awful distance between justice and grace. She said that cop-killers like him should be electrocuted and she would be happy to pull the switch herself. She used ALL CAPS as I recall. There is a category of grace for Thomas Aquinas that is the grace God gives a person not for their own benefit but for another. I do not think there is a category for the opposite given by the evil one, but there should be. This poor woman was blinded by the ostensible gulf that exists between those in prison and the free. She thought that unlike Anthony, being on the far side of the prison wall meant that she was able to face that justice she was now so eager to inflict upon her pen pal. I have always prayed that Anthony had come to know better. I believe he did.

So why is it so eternally important that we befriend prisoners and find Christ in that act? My answer is idiosyncratic, to be sure, but I hope it touches upon the truth nonetheless. When we visit a prison, we enter into a privileged place of justice in a world in which only a thin slice of the evil committed is ever accounted for, including, of course, our own nasty contributions. In that way, our visit is in a real way required to restore a bit of balance to the scale. More than that, the justice that prison represents can, if we are willing, instruct us on our own need for grace.

One last story. Out of nowhere the local bishop offered to say the triduum in the prisons; Good Friday was in the Federal camp. Since the Southern Baptist chaplains had no such service, the Protestant inmates could, if desired, join the Catholics. The Protestantism I witnessed in prison was of an austere variety and I quickly began to worry about how the various parts of the Good Friday service would be received, especially the slightly pagan kissing of the crucifix.

A few minutes before the bishop was to begin, about twenty African-American inmates walked in. We had heard about them and especially their leader, an impressive figure named Willie. When we got to that moment when the bishop intoned “let us kneel,” all eyes shifted immediately to Willie. There was obvious concern that they were being tempted by Romanish idolatry. After a long moment, Willie nodded his head ever so slightly and all twenty hit the floor as one. A place of privilege indeed.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay was first delivered at the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture Fall Conference in 2019.

CHURCH LIFE JOURNAL

No comments:

Post a Comment