|

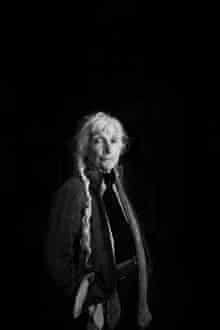

| Renata Adler at Morgan Library, New York. Photograph: Sarah Wilmer for the Observer |

In New York, Renata Adler has a reputation so burdensome and fierce, you half expect it to take a physical form. It could be on her back, like a rucksack, or it could be in her hand, like a gun. So when I spy her scurrying out of the Morgan Library some 20 minutes before we’re due to meet – thanks to a bad case of nerves, I arrived at the cafe of this august Madison Avenue institution a full half hour early – it takes me a while to get over the surprise of her tiny handbag, her loose trousers, her soft sneakers and her red anorak. Apart from her famous plait, a dramatic grey rope that falls just shy of her waist and almost cries out to be stroked – or perhaps yanked – she looks to me much like any other country mouse come up to the city for the day (she lives in Newtown, Connecticut, in an old cider mill close to where she grew up). Her steps are miniature, almost hesitant, and as she walks, her head moves quickly from side to side. What, I wonder, is she looking for? A newspaper stand? A chemist? A branch of Dunkin’ Donuts?

“A comb!” she cries, half an hour later. “I was trying to find some place to buy a comb!” She pats her scalp distractedly. “I thought I’d better tidy myself up. Because I must look so awful.” Was she successful? “No. I couldn’t find anywhere. It’s quite amazing. And I walked a few blocks, too.” Her tone is bewildered and a touch disappointed, as if the city were a student who had failed to turn in an important essay.

Once upon a time, Renata Adler, who could not look awful even if she tried, was very famous and very cool: “Lena Dunham many times over,” as her friend, the writer Michael Wolff, puts it. A big name at the New Yorker in the days when that magazine was (to quote him again) as unmissable as HBO is now, and the author of two critically acclaimed modernist novels – Speedboat was published in 1976 and Pitch Dark in 1983 – she might have been Joan Didion’s younger and slightly more pugnacious sister (Adler was born in 1938, four years after Didion). Clever, beautiful, opiniated and ever watchful, she was a meteor: dazzling and unstoppable. Everyone wanted her, even Richard Avedon, who photographed her in 1978, and made her look every bit as charismatic and sexy as Katharine Hepburn. (Not that she sees it that way. “I look like a terrorist,” she says. “Or at least, like a hijacker, and they were the only terrorists in those days.” A pause. “He [Avedon] had gone from fashion to freaks.” Another pause. “I seemed to be the first in his freak series.”)

But then, something happened. Adler happened: her quarrelsome nature, her low tolerance for fools and frauds, and her seeming inability to tell lies, white or otherwise, brimming suddenly and dramatically to the surface. In 1980, though still a New Yorker writer herself, she reviewed When the Lights Go Down, a collection by the magazine’s powerful film critic, Pauline Kael, for the New York Review of Books. She didn’t hold back. The piece, which was 8,000 words long, accused Kael of being a demagogue and her book of being “jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption, worthless”.

Needless to say, this did not go down well with the members of what Adler referred to as Kael’s cult, nor with her bosses at the New Yorker. The facts – that she was not, or not entirely, wrong (Kael was a bit on the windy side), and that her essay strove to make a more general point about the queasy nature of writing on one subject, week in, week out – were not taken in mitigation (in the 1960s, Adler had spent a year as the film critic of the New York Times and was thus in a position to know all about hack work). She had committed journalistic sororicide, and though she could not immediately be punished for this, her first offence, her colleagues could at least blow a cool breeze in her direction.

Offence No 2 was committed in 1999, when Adler published a book called Gone: The Last Days of the New Yorker. Its targets were many and various – “As I write this, the New Yorker is dead,” reads her first line – but she reserved her most elegant ire for Robert Gottlieb, who had replaced William Shawn (aka the legendary Mr Shawn) as the editor of the magazine in 1987, and for the writer Adam Gopnik, one of his protégés.

New York being a pretty self-regarding, self-referential kind of a place, Gottlieb reviewed Gone for the New York Observer. (Gottlieb, by the way, had edited one of Adler’s novels in his previous incarnation as editor-in-chief of Knopf; he thought they were friends.) “Her book reflects a dangerous arrogance,” he wrote. “Whatever Renata says or does is, by definition, right.” His explanation for her unaccountable trashing of her colleagues was pseudo-Freudian. “To a large extent, this book is an explosion of pain and anger from someone caught up in the dynamic of a highly dysfunctional family,” he noted. Apparently, Daddy (ie Mr Shawn) had let Renata down. Her distaste for Gopnik, whom she derided in her book as a “meaching” brown-nose and arch manipulator, he regarded as “sibling rivalry”.

To us, and with the distance of years, all this sounds laughably incestuous: a squall in a Monday morning latte. (An entire book, about a few journalists on a dusty magazine!) But at the time, and in New York, it was a Big Deal. For Adler, the shutters came down, and quickly. In the weeks that followed the publication of Gone, the New York Times published no fewer than eight negative articles about her “irritable little book” and ran a leader questioning her ethics. Her relationship with the New Yorker irredeemably soured and, other newspapers and magazines lining up to send her to Coventry, she found herself not only without a berth, but without any work to speak of. And so the wilderness years began.

Now, though, it’s all change again. Following a campaign by the National Book Critics Circle and by the super-fashionable writer David Shields, who claims to have read Speedboat some 24 times, her two novels are finally back in print, a development that has been widely welcomed even by the New York Times. As a result, delightful profiles of Adler have appeared in, among others, New York magazine and the Believer. “Welcome Back”, say the headlines. Elsewhere her many fans have lined up to acclaim her particular brand of what Katie Roiphe calls Smart Women Adrift fiction (according to Roiphe, who shares her contrarian instincts and a good deal of her bravery, Adler is the absolute mistress when it comes to conveying “the exhaustion of trying to make sense of things that don’t make sense”). She is even being offered work again, most recently quietly dissing a new biography of her former New Yorker colleague Saul Steinberg in Town & Country.

Is David Remnick, the present editor of the New Yorker, about to call? What would she do if he did? “It’s totally unimaginable,” she says, in her wry but rather fluttery way. “The ostracism has been complete from the day he got there. I did call him once. I wanted to review the special counsel report into Bill Clinton. After all, I’d worked for an impeachment inquiry before [in the 70s, she was a writer for the Watergate committee, a job that involved making the nation’s lawmakers sound articulate and suitably grave]. He said: ‘Frankly, Renata, I’ve had enough Monica Lewinsky pieces.’ Well, I don’t write Monica Lewinsky pieces! So I called Graydon [Carter, the editor of Vanity Fair], and he was wonderful, and I wrote it for him.” (She is too polite to say so now, but she went on to pick up an award for “Decoding the Starr report”, the piece in question.)

But she is happy to be working again? “Of course. Having no job is a problem. One needs an apartment and a job; these things are helpful. I need the money. I’ve run out! The fantasy is to be able to do a certain kind of journalism in a safe place. Setting one’s own deadline is difficult, you see. I get too isolated. I think: Is it Monday? Is this Alzheimers?”

Her advice to writers is: cling to your day job – wherever it happens to be – for as long as you possibly can. “I’ve said it all along, in my even way: if you’re at Condé Nast, and they’re cutting your pieces to shreds, just hang on. Do your art in your own time, but don’t quit because then you’ll be out there, vulnerable. When I left the New Yorker, I was fair game. There is a little bit of fear when you have a connection [to a media institution], no matter how tenuous and no matter how disreputable the organisation.”

Has she spoken to Gottlieb since? “I saw him at the railway station after the funeral of Kay Graham [the owner of the Washington Post]. I started to speak, but then I realised he probably wasn’t going to say hello back.” Doubtless she found out who her friends were in those years. “Yes. One has none, or practically none. And I minded more than I expected. It was lonely and paranoid-making. Of course, I’d already been through this in school.” She looks at me. “Were you an outcast in school?” Sort of, I say. I certainly didn’t fit in. “Well, me too.” Does she think any of the backlash was due to her sex? It seems to me that men can be utterly vile in print and get away with it, whereas a woman has only to speak her mind to be considered a bitch. (After all, the journalist James Wolcott has mightily slagged off Adam Gopnik and he is still in work.) “I think that’s absolutely right. Shrill. I’ve been described as shrill. Isn’t that strange? When feminism began, I thought: well, it hasn’t been a problem for me, being a woman. But now I look back and I notice…” Her voice trails off.

The pity of it is that Adler is very far from being shrill. In person, she is warm and slightly kooky, her tone ironic and, as she has already pointed out, even. On the page, she is wise and clear and forensic. Nothing gets by her, whether she is writing about Nixon or Biafra or afternoon television (subjects which are all covered in Canaries in the Mineshaft, an envy-inducing collection of her journalism that came out in 2001). The same is true of her novels, now so handsomely published by New York Review Books Classics, for all that their style is at first so unexpected.

Of the two, Speedboat is the more radical. Ostensibly, it tells the story of Jen Fain, a journalist at the Standard Evening Sun, and her adventures with a series of men. But it has no plot to speak of. Rather, it is a collection of shards, sharp and shiny, the narrative moving disconnectedly and back and forth. You would call it stream of consciousness if it wasn’t, at times, so beady; if each of its sections weren’t so corruscating, so beautifully observed. She has literary parties just right: “Some people, in a frenzy of antipathy and boredom, were drinking themselves into extreme approximations of longing to be together. Exchanging phone numbers, demanding to have lunch, proposing to share an apartment – the escalations of fellowship had the air of a terminal auction, a fierce adult version of slapjack, a bill-payer loan from a finance company, an attempt to buy with one grand convivial debt, to be paid in future, an exit from each other’s company that instant.” And her juxtapostions are quite brilliant. Sitting in front of the Watergate hearings, Fain sees a TV ad in which “a hideous family pledged themselves to margarine”.

Pitch Dark is slightly less episodic – its narrator, a journalist called Kate Ennis, is in love with a married man, a relationship that gives the narrative some structure – but it, too, is replete with dark truths. On journalism, for instance, the book is unnervingly prescient: Ennis loathes the elevation of rumour, the “odd notion that fiction was just a matter of getting facts completely, implausibly wrong”. For all its modernism, Adler’s sensibility is in every sentence, in every clause.

What’s it like to see the books back in print? “It’s a strange feeling. They seem kind of familiar. But I never reread stuff. It’s so painful.” When they were written, the books amazed her as much as anyone else. “I didn’t expect them to come out like this because this isn’t the kind of fiction I like to read. I mean, I read John le Carré!” Did she feel, as a young woman, that she couldn’t call herself a proper writer until she had written a novel? (Quite a lot of talented journalists feel like this, I’ve no idea why.) “Not as a journalist, no. But as a critic, I felt: it isn’t fair to keep offering all these opinions. So, I thought I’d write some fiction. But it’s interesting. The minute you say ‘this is fiction’, it changes everything. The test with journalism is: do the facts check out? Is it true? Is it of some importance? That’s not so with fiction. Though this is less and less often the case, of course.”

Her voice becomes conspiratorial. “Have you read as much junk as I have? We must talk about junk! Facts are becoming harder and harder, more elusive. We’re in a muddle, a mess. There’s such a racket going on. There are so many lies around, readers are beginning to think: don’t bother me with whether this is true or not true; I’m busy.” In this world, she thinks, fiction is sometimes, and perhaps increasingly, the best way to tell “the truth”.

Not that she finds any kind of writing easy, exactly. “I have such problems doing it at all. It’s horrible. Why didn’t we choose to do something else?” For her, writer’s block set in early. After growing up in Connecticut – her parents were refugees from Nazi Germany – she went to Bryn Mawr, the women’s liberal arts college near Philadelphia. “I wasn’t turning in any papers because I didn’t want to be there. So the school said: you’ll have to see a psychiatrist. At which point, my brother said: this is ridiculous, I’ll write your papers for you. He was a mathematician, so they weren’t right, of course [Adler was studying German and philosophy], but because he had given me this safety net, I found I could write them for myself. It made the thing possible.” She looks at me. “I certainly wasn’t going to be a writer after that, though.”

After Bryn Mawr, she studied for a postgraduate degree at Harvard (she is super-bright: in the 70s, she got a degree from Yale Law School, apparently just for the hell of it), and it was while she was there that it was suggested to her that she go and see the New Yorker. This she did, only to be told that there were no jobs available. “But they said: why don’t you take these manuscripts with you? In college, we didn’t read anything contemporary, with the result that I loathed them all. Well, I sort of loathed them all. So I wrote masses about them, and turned in these very careful reports. Then they said: come back in three months, and we’ll hire you for something.” She laughs. “Well, in those three months, pretty much all those manuscripts ran in the magazine, and they were all by New Yorker stars.” No matter. In 1962, she became a staff writer.

It was quite a strange place to work. No one seemed to know exactly what their job entailed, and Mr Shawn had installed a particularly weird payment method whereby writers borrowed money against their future work. “Some of the older writers were waiting to see who would die most in debt to the New Yorker,” she says, with another hoot of laughter. “Some of the most boring writers in the world had huge drawing accounts, which meant that when they did write something, the magazine was almost obliged to run it.” Mr Shawn was so enigmatic a boss that some writers did not even realise they had been hired (or fired, come to that). “One writer thought he had been fired, and so he went to Newsweek. Mr Shawn saw him one day and said: ‘We haven’t seen you around here lately.’ When he said he was at Newsweek, Mr Shawn looked very hurt and disappointed. He hadn’t been fired at all.”

The first piece she wrote was about pop music. But it never ran. “Mostly, I was a book reviewer. They’d run one every half year! So I asked Mr Shawn if I could go south, report on the civil rights movement, and he said yes. And I loved reporting. I was so lucky. It unfolded in time, so the structure was given, and the characters were so colourful, and you could tell who the good guys were, and who the bad guys were. There aren’t stories like that now.” She had found her place in the world. Later, she would report from both Vietnam and Biafra.

No wonder, then, that she was somewhat amazed by the reaction to her piece about Kael. It seemed such a small thing, and not, in any case, unjust. “It’s hard to imagine her power then,” she says. “She had this little group. In a way, it wasn’t her fault. No one said ‘stop’.” Adler had resigned her post as the New York Times chief film critic after just a year, and found it hard to understand how Kael could keep on keeping on. “Who wants to hear somebody’s opinion every other day? Everybody has opinions about films anyway, so who wants to hear the shrew that is oneself? To do this for years and years?” Criticism does not allow one to be equivocal, or only very rarely, and this, she thinks, is perhaps its primary failing: “Sometimes, I like things on one day, and not on another.” Nor has it escaped her notice that even as people become – thanks largely to the internet – ever more opinionated, the sane among us find it increasingly difficult to believe in anything: “I used to know what I thought politically. Now I don’t like anybody, which is a position, but not a very useful one.”

What, I wonder, does she think she has sacrificed along the way for her work – apart, of course, from the friendship and good opinion of certain of her former colleagues? “I can’t think of anything,” she says. “There wasn’t going to be any life without it [work]. That’s just the way it was.” She has a son, whose father’s name she has never revealed. “He’s 27. I brought him up alone. I’m not sure what effect I’ve had on him. His father said: ‘It doesn’t matter what you do with children; they will turn into what they will turn into.’ But in any case, I’m not sure anyone brings anybody up any more.”

She is thrilled about the return to print of her novels – “It’s all you can hope for as a writer, though they may still be terrible in some way I hadn’t suspected” – and has a third ready to be sent to her agent. “Yes, somebody else is going to read it. And then, I suppose, there’ll be some rewriting.” A weary sigh. “This horrible business. No one has asked me to rewrite anything in a long time. But then, I haven’t written anything in a long time.” She smiles, mournfully.

Will she sign a copy of Pitch Dark for me? “Oh, yes,” she says. She grabs my pen, and scribbles happily away. It’s only when I get back to my hotel room that I notice at what an odd angle her words have been written. Like their author, they stand apart. They seem to be marching towards the page’s far corner, making their point in capital letters even as they head for the door.

THE GUARDIAN

No comments:

Post a Comment