Walter Benjamin in Ibiza

By Frédéric PajakMarch 20, 2019

When Hitler came to power, Walter Benjamin did not immediately realize what the dictatorship had in store. Like many intellectuals, he counted on an early collapse of the regime. To begin with, he seemed almost serene in the face of events. But events picked up speed, and, even though it was hard to obtain reliable news, by March 1933 it was apparent to him that “there can be no doubt that in very many instances people have been dragged from their beds in the night and beaten or murdered.”

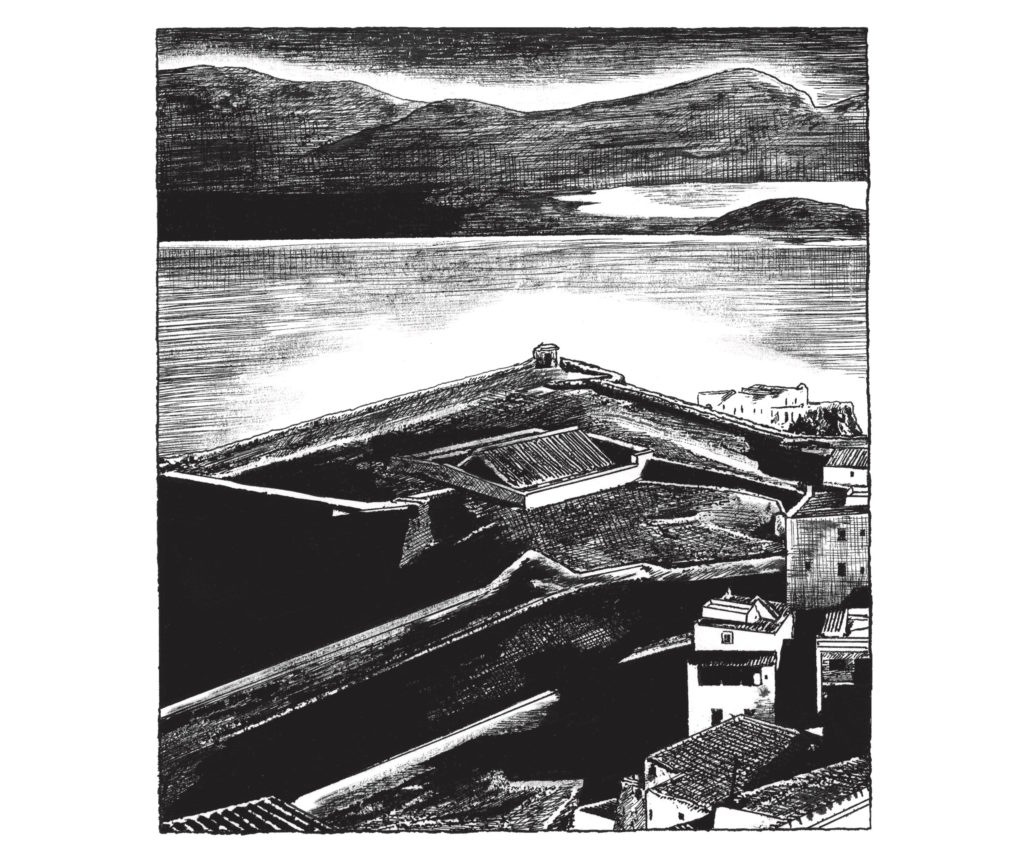

In 1928, during an exchange with André Gide, Benjamin compared Gide’s thought to a fort, “vast in its overall structure, replete with protective ramparts and protruding bastions, and above all strict in its forms and perfect in its deliberate dialectical construction.” Was this a self-portrait of Benjamin himself?

Benjamin wrote that Gide had quoted Louis Antoine de Bougainville: “When we left the island, we called it Île du Salut” (Salvation Island). And Gide added that “it is only when we leave something that we name it.”

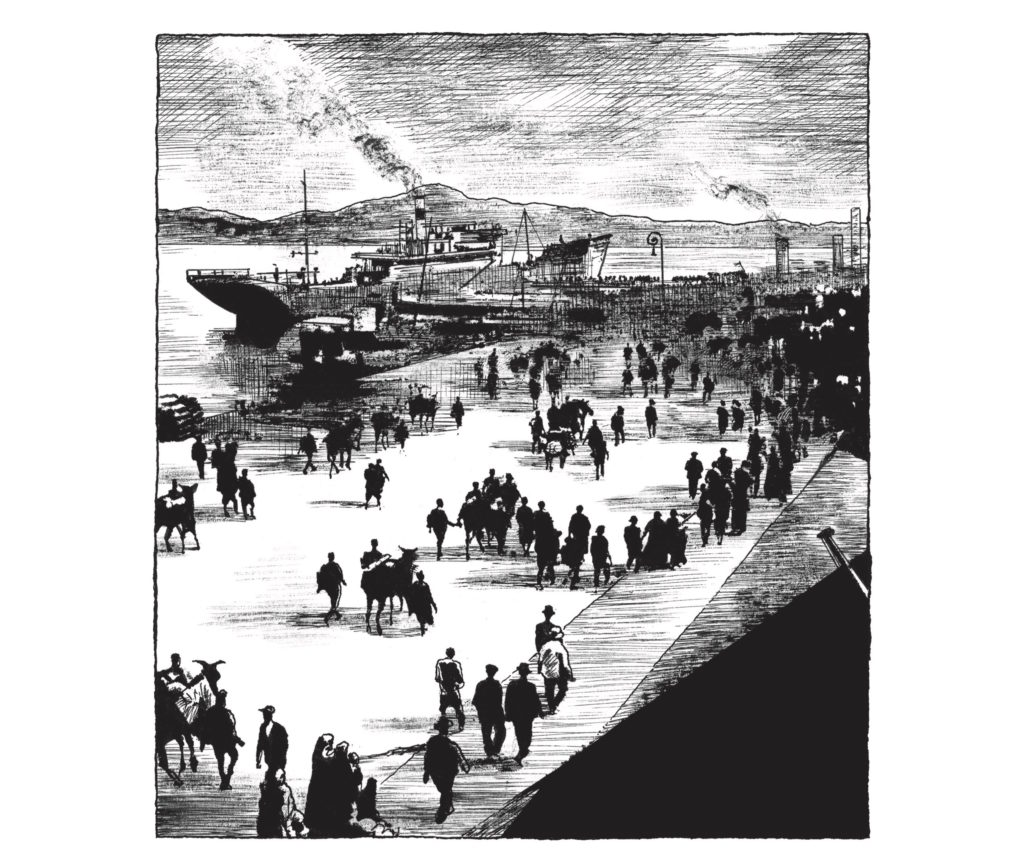

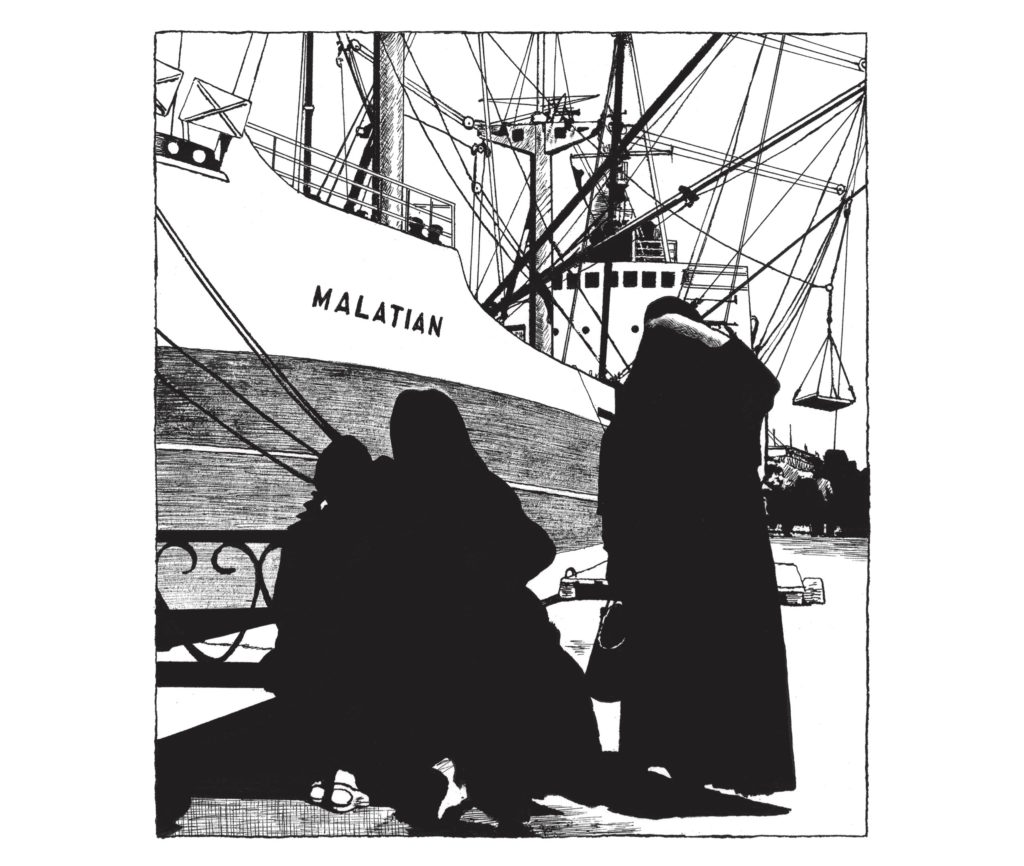

Tuesday morning, April 19, 1932. After an overnight crossing, the Barcelona-Ibiza ferry Ciudad de Valencia tied up at quayside. Benjamin disembarked from a third-class cabin and walked slowly and stiffly over to the friend who had come to the port to greet him.

Felix Noeggerath and Benjamin had first met fifteen years earlier, while taking classes on the Mayans and Aztecs along with Rainer Maria Rilke. A native of Berlin, Noeggerath had emigrated to San Antonio Bay, some fifteen kilometers from Ibiza Town, with his third wife, the beautiful Marietta, his son Hans Jakob, a philologist, and his daughter-in-law.

Noeggerath had Benjamin’s deep admiration as a doctor of philosophy, who was passionate about history, theology, mathematics, and linguistics. Benjamin did not hesitate to call him a genius, while in Noeggerath’s eyes Benjamin was the genius. But barely had these two geniuses found one another again when they discovered that the same crook had swindled them both—by renting a house on Ibiza that he did not own to Noeggerath and by occupying Benjamin’s flat in Berlin without paying the rent. Aside from the financial issue, Benjamin worried about his manuscripts, which the man might have taken with him when he fled. He considered going back to Berlin, but upcoming national socialist festivities dissuaded him.

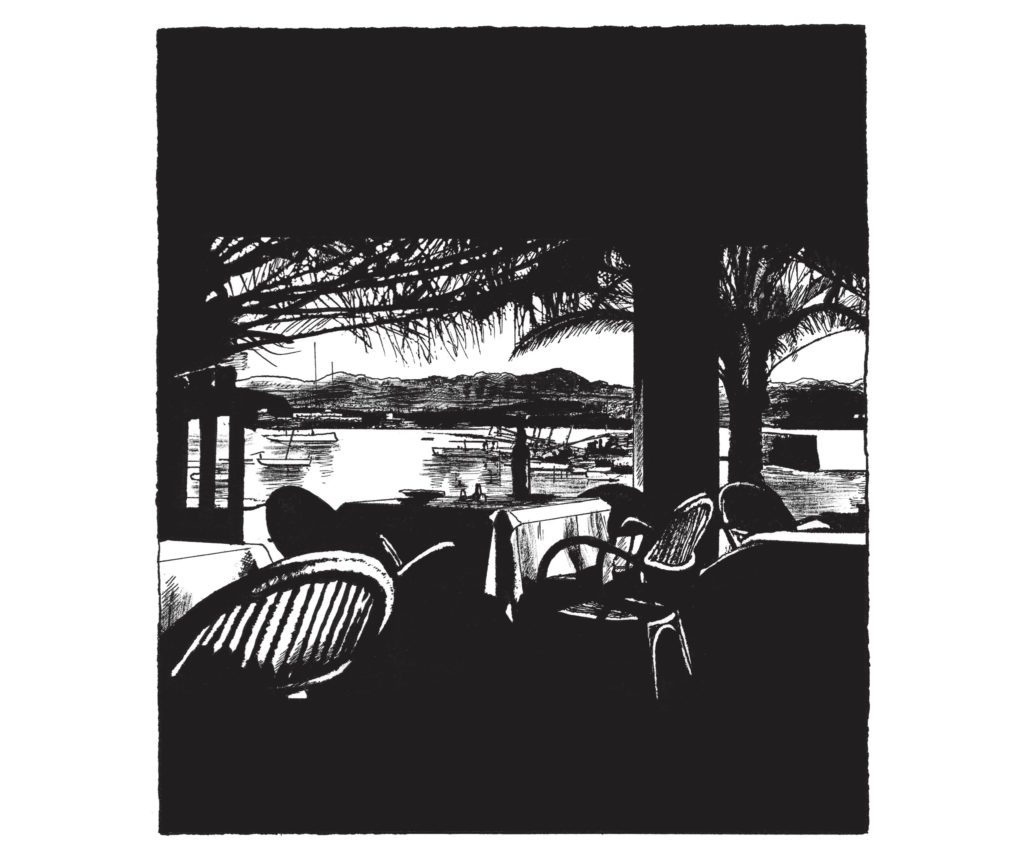

On Ibiza, Benjamin stayed at first with the Noeggeraths. In the daytime he would attempt to escape the promiscuity and chatter there by losing himself in “the age-old beauty and solitude of the region.” He would rise at six or seven, swim in the sea, and gaze off into the distance. Then he would take refuge in the forest undergrowth. He read, scribbled, and sunbathed leaning against a tree trunk. In this way he spent many long days deprived of almost everything—of “electric light and butter, liquor and running water, flirting and reading the paper.”

Around two o’clock he would go back for lunch with his hosts and play cards or dominoes for a while before going to dawdle in the café. At nine in the evening, or ten thirty at the latest, he would retire to his room—a room that he shared with “three hundred flies”—and plunge into a book.

What did he read? For one thing, Trotsky’s autobiography, which took his breath away.

Subsequently he lived in a little house that he had to himself, and ate three meals a day, local cooking for which he paid 1.80 marks.

The island of Ibiza—or Eivissa—in the Spanish Balearic archipelago is an intact repository of a living antiquity without ruins or remains. An heir to Carthage and the Moors, Ibiza has preserved its Phoenician, Roman, and Arab heritages, despite Spanish hegemony. Ibiza is the most African of the Balearic Islands. Pottery and figurines of Ishtar, the dove goddess, and Ba’al, the goat god, are still made there just as they were two thousand years ago.

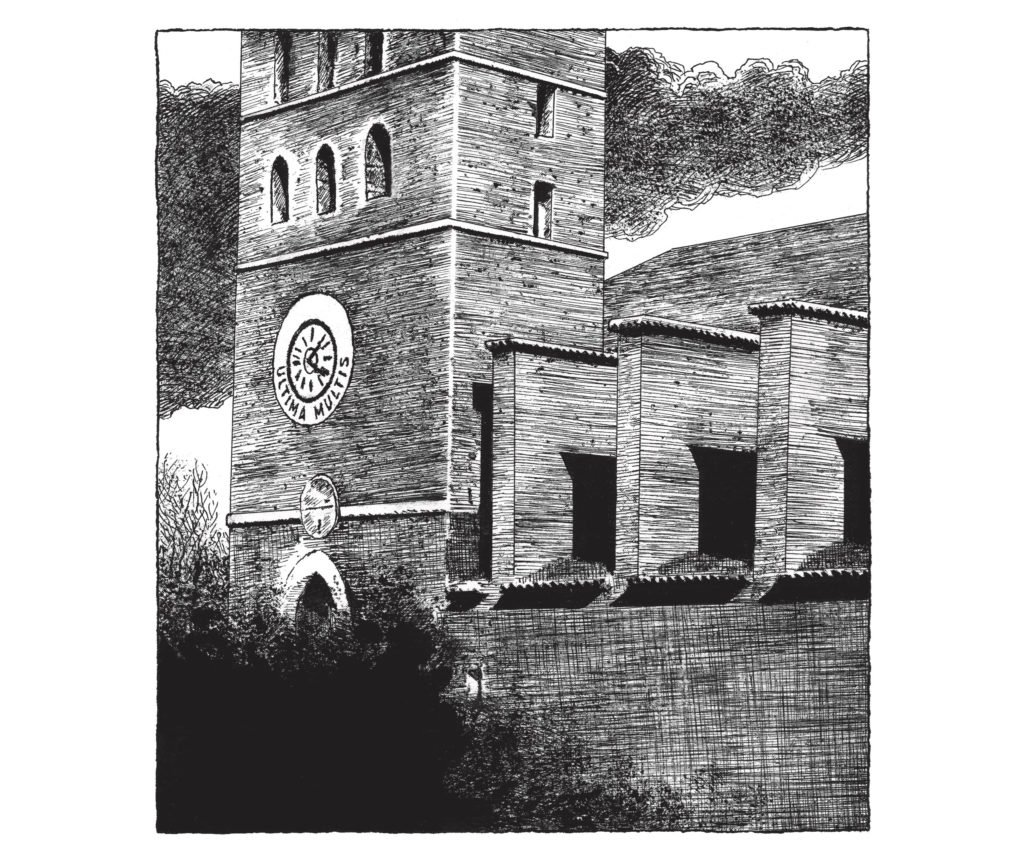

The Ibiza cathedral clock bore the inscription Ultima multis—“the last day for many.” This maxim made a strong impression on Benjamin.

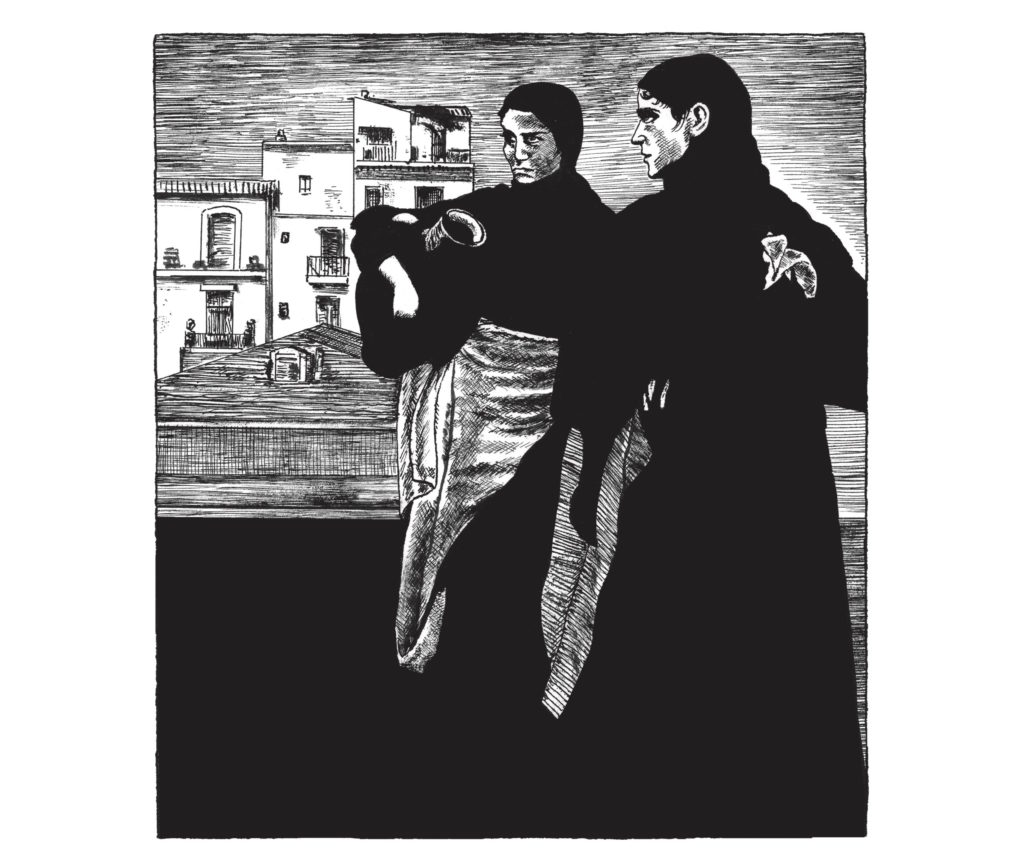

The costume of the women consisted of a long-sleeved bodice covered by a shawl and a silk brocade dress pleated in the back, falling to the ankles and protected by a pinafore. Its billowing aspect could be explained by the fact that beneath it were at least ten underskirts.

Passing through the island, Albert Camus noted that “if the language of these places was in harmony with what resonated profoundly within me, it was not because it answered my questions but rather because it rendered them superfluous.”

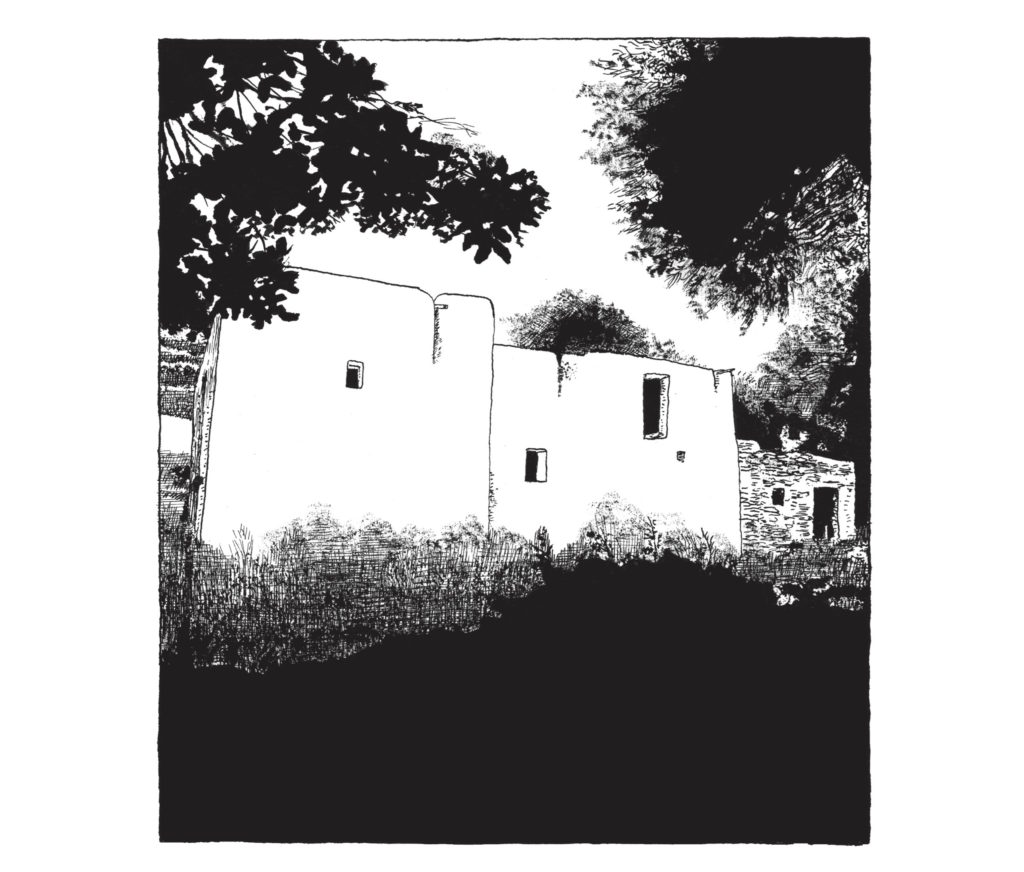

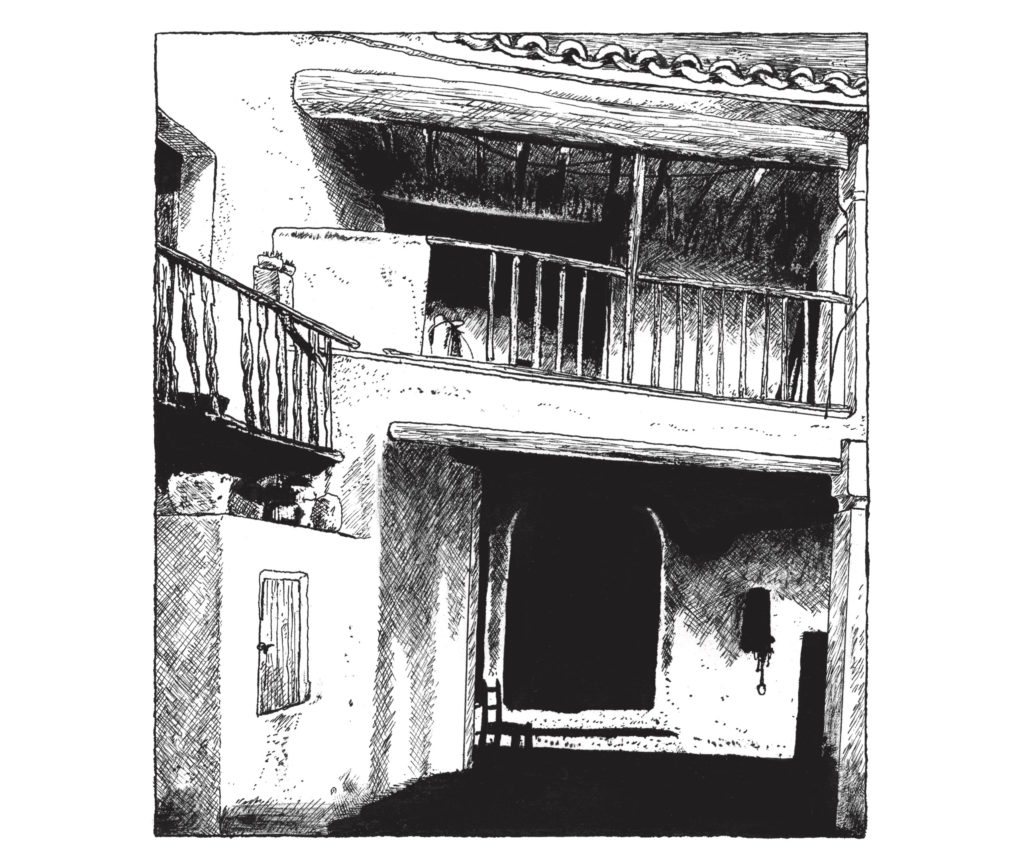

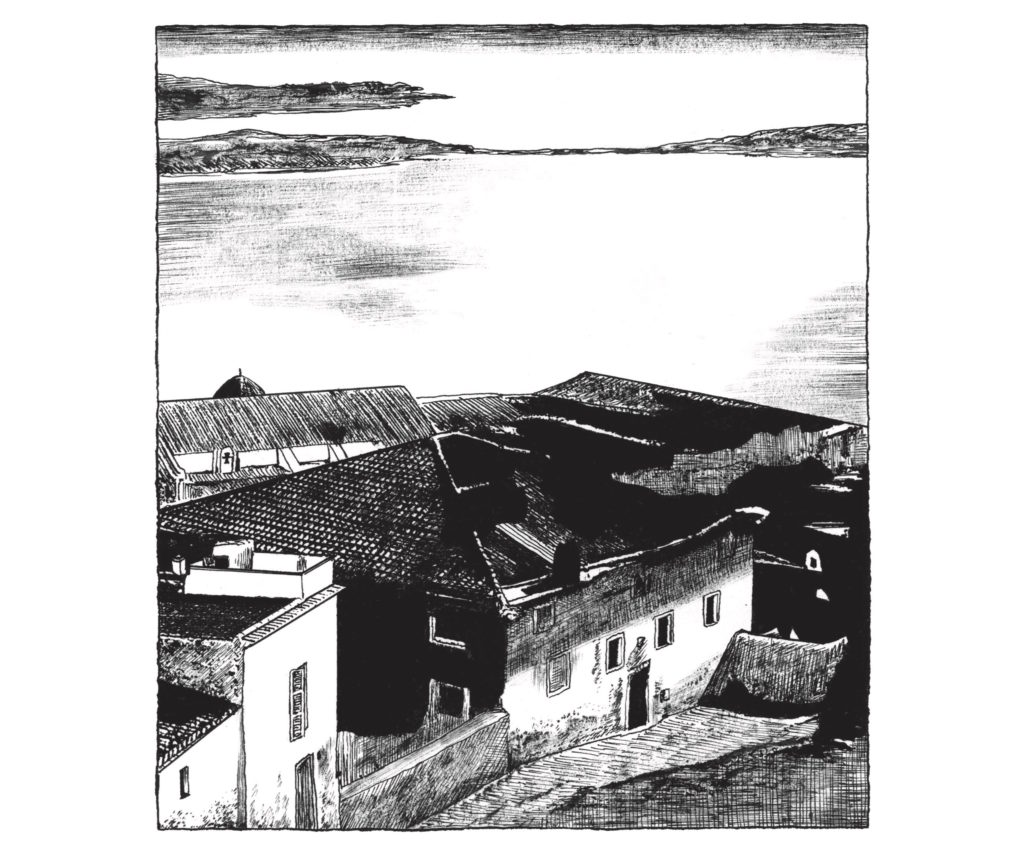

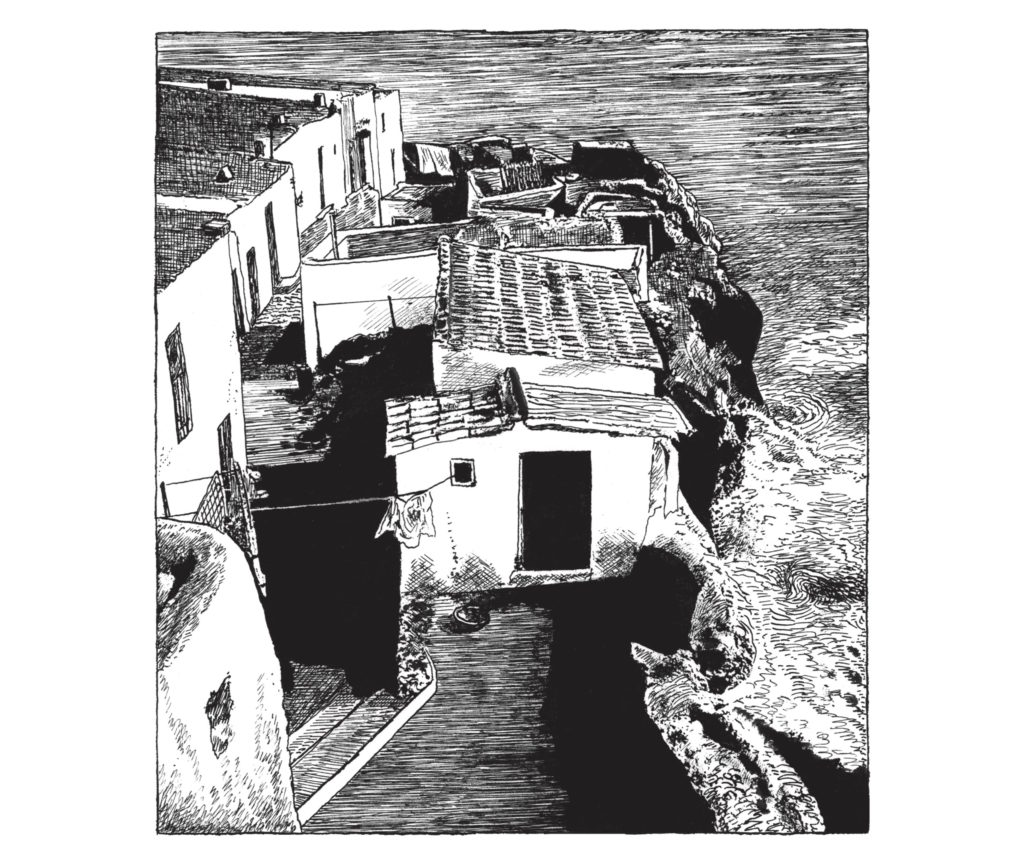

On this “island of forgetfulness” the inhabitants themselves conceived and built their dwellings as “peasant palaces,” the legacy of an ancient Egyptian architecture. Benjamin was entranced by this architecture sans architects, by its sobriety, and by the way it bore witness to the relationship between the Ibicencos and their landscape. It was a vernacular style in which, “defying the shadows, the gleaming white of the walls dazzles you.”

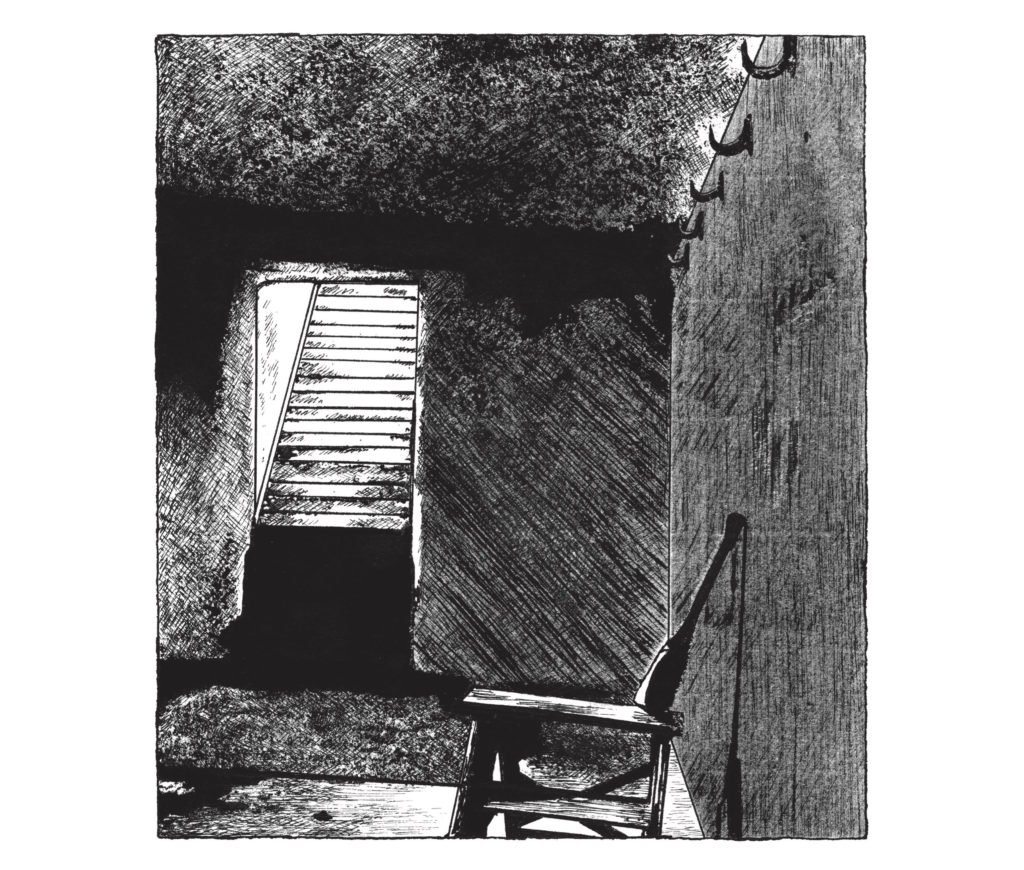

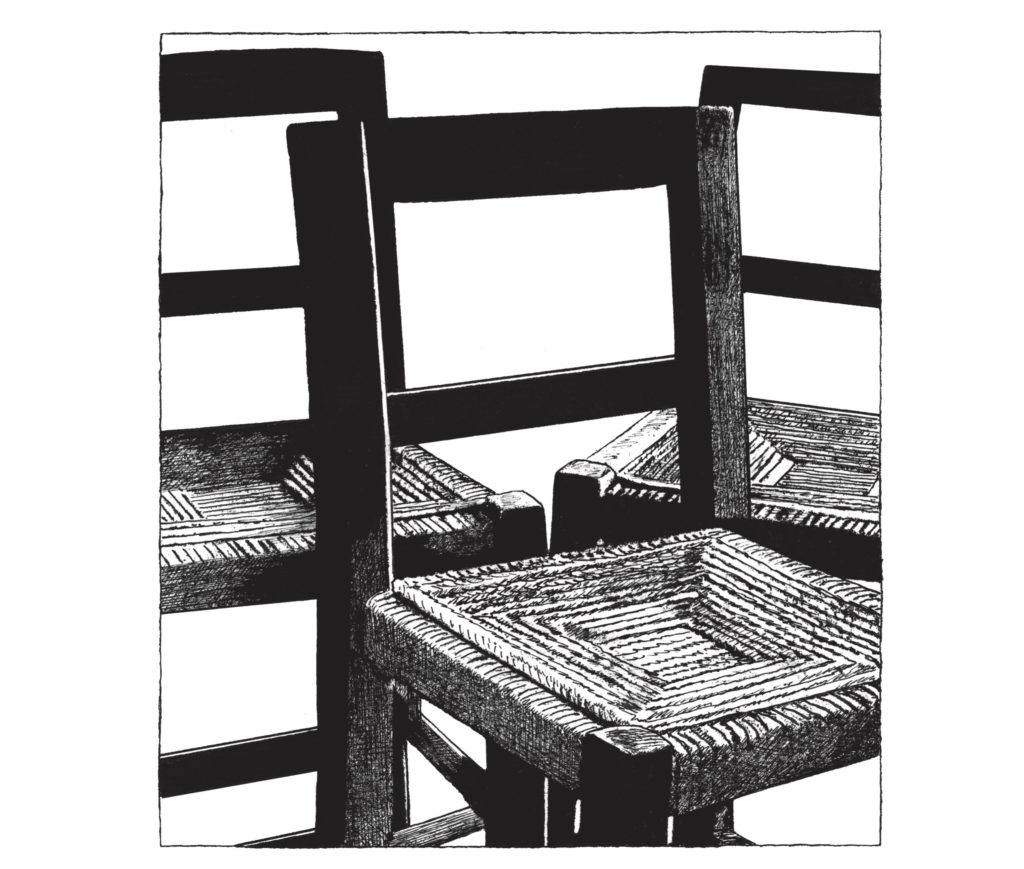

And in the main room, chairs of an overwhelming simplicity were always carefully arranged—chairs which, according to Benjamin, “had much to tell.”

Unchanged for centuries, ignored by the rest of Europe, Ibiza began in the thirties to become a focus of interest for travelers and a place of refuge for others. In 1932, however, it was still bypassed by international trade and modernity in general, whose conveniences simply did not exist there. Benjamin had no complaints. For the time being, he enjoyed a kind of contentment enhanced by the splendor of the landscape—the “most untouched” he had ever seen.

Farming and animal husbandry were still “carried on in an archaic manner—there are not more than four cows on the whole island, as the peasants keep to their traditional goats; no agricultural machinery is to be seen and the irrigation of the fields is effected, as it was centuries ago, by means of water scooped up by bucket wheels drawn by mules.”

From his room Benjamin had a view of the sea and of a rocky island illuminated at night by a lighthouse. “It is unfortunately to be feared,” noted Benjamin, “that the construction of a hotel at the port signals the end of all this.”

During this first stay on Ibiza, Benjamin formed a liaison with Olga Parem. They decided to explore the island together and went for long outings on foot and by boat. As soon as he proposed marriage to her, however, she left him.

Three months after his arrival, Benjamin returned to France by way of Majorca. He reached Nice on July 22 and checked in at the Hôtel du Petit Parc. Exhausted, and perhaps depressed by the breakup with Olga, he abruptly decided to take his own life. He drew up a will and sent letters of farewell to his close friends. But he did not proceed. And offered no explanation.

—Translated from the French by Donald Nicholson-Smith

Frédéric Pajak is a Swiss French writer and graphic artist born in Suresnes, France. He has written novels and film scripts, and he is a painter, as was his father, Jacques Pajak. He has edited and contributed to cultural and satirical periodicals and is the editor of the highly illustrated biannual journal Les Cahiers dessinés, devoted to graphic work ranging from cartooning to the drawings of old masters. But Pajak is best known for a long series of books of unique design which present his own full-page drawings accompanied by a biographical and autobiographical quasi narrative. The first of these works, which made his reputation, was L’immense solitude (1999), which won the Prix Michel Dentan in 2000. He followed this with another similarly structured work, Le chagrin d’amour (Broken hearts), which dealt with Guillaume Apollinaire. Later subjects included Joyce, Luther, Freud, Nietzsche, Cesare Pavese, and Schopenhauer. In the same formal vein, Pajak’s ongoing Uncertain Manifesto, which began with the present work in 2012, reached its seventh volume in 2018. The third volume was awarded the Prix Médicis (Essai) in 2014.

Donald Nicholson-Smith’s translations of noir fiction include Jean-Patrick Manchette’s Three to Kill; Thierry Jonquet’s Mygale (a.k.a. Tarantula); and (with Alyson Waters) Yasmina Khadra’s Cousin K. He has also translated works by Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Henri Lefebvre, Raoul Vaneigem, Antonin Artaud, Jean Laplanche, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Guy Debord. For New York Review Books, he has translated Manchette’s Fatale, The Mad and the Bad, Ivory Pearl, and Nada and Jean-Paul Clébert’s Paris Vagabond, as well as the French comics The Green Hand, by Nicole Claveloux, and Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures, by Yvan Alagbé. Born in Manchester, England, he is a longtime resident of New York City.

Excerpted from Uncertain Manifesto, by Frédéric Pajak, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, published by New York Review Books. Copyright © 2012 by Les Éditions Noir sur Blanc, Lausanne. Translation copyright © 2019 by Donald Nicholson-Smith

When Hitler came to power, Walter Benjamin did not immediately realize what the dictatorship had in store. Like many intellectuals, he counted on an early collapse of the regime. To begin with, he seemed almost serene in the face of events. But events picked up speed, and, even though it was hard to obtain reliable news, by March 1933 it was apparent to him that “there can be no doubt that in very many instances people have been dragged from their beds in the night and beaten or murdered.”

In 1928, during an exchange with André Gide, Benjamin compared Gide’s thought to a fort, “vast in its overall structure, replete with protective ramparts and protruding bastions, and above all strict in its forms and perfect in its deliberate dialectical construction.” Was this a self-portrait of Benjamin himself?

Benjamin wrote that Gide had quoted Louis Antoine de Bougainville: “When we left the island, we called it Île du Salut” (Salvation Island). And Gide added that “it is only when we leave something that we name it.”

Tuesday morning, April 19, 1932. After an overnight crossing, the Barcelona-Ibiza ferry Ciudad de Valencia tied up at quayside. Benjamin disembarked from a third-class cabin and walked slowly and stiffly over to the friend who had come to the port to greet him.

Felix Noeggerath and Benjamin had first met fifteen years earlier, while taking classes on the Mayans and Aztecs along with Rainer Maria Rilke. A native of Berlin, Noeggerath had emigrated to San Antonio Bay, some fifteen kilometers from Ibiza Town, with his third wife, the beautiful Marietta, his son Hans Jakob, a philologist, and his daughter-in-law.

Noeggerath had Benjamin’s deep admiration as a doctor of philosophy, who was passionate about history, theology, mathematics, and linguistics. Benjamin did not hesitate to call him a genius, while in Noeggerath’s eyes Benjamin was the genius. But barely had these two geniuses found one another again when they discovered that the same crook had swindled them both—by renting a house on Ibiza that he did not own to Noeggerath and by occupying Benjamin’s flat in Berlin without paying the rent. Aside from the financial issue, Benjamin worried about his manuscripts, which the man might have taken with him when he fled. He considered going back to Berlin, but upcoming national socialist festivities dissuaded him.

On Ibiza, Benjamin stayed at first with the Noeggeraths. In the daytime he would attempt to escape the promiscuity and chatter there by losing himself in “the age-old beauty and solitude of the region.” He would rise at six or seven, swim in the sea, and gaze off into the distance. Then he would take refuge in the forest undergrowth. He read, scribbled, and sunbathed leaning against a tree trunk. In this way he spent many long days deprived of almost everything—of “electric light and butter, liquor and running water, flirting and reading the paper.”

Around two o’clock he would go back for lunch with his hosts and play cards or dominoes for a while before going to dawdle in the café. At nine in the evening, or ten thirty at the latest, he would retire to his room—a room that he shared with “three hundred flies”—and plunge into a book.

What did he read? For one thing, Trotsky’s autobiography, which took his breath away.

Subsequently he lived in a little house that he had to himself, and ate three meals a day, local cooking for which he paid 1.80 marks.

The island of Ibiza—or Eivissa—in the Spanish Balearic archipelago is an intact repository of a living antiquity without ruins or remains. An heir to Carthage and the Moors, Ibiza has preserved its Phoenician, Roman, and Arab heritages, despite Spanish hegemony. Ibiza is the most African of the Balearic Islands. Pottery and figurines of Ishtar, the dove goddess, and Ba’al, the goat god, are still made there just as they were two thousand years ago.

The Ibiza cathedral clock bore the inscription Ultima multis—“the last day for many.” This maxim made a strong impression on Benjamin.

The costume of the women consisted of a long-sleeved bodice covered by a shawl and a silk brocade dress pleated in the back, falling to the ankles and protected by a pinafore. Its billowing aspect could be explained by the fact that beneath it were at least ten underskirts.

Passing through the island, Albert Camus noted that “if the language of these places was in harmony with what resonated profoundly within me, it was not because it answered my questions but rather because it rendered them superfluous.”

On this “island of forgetfulness” the inhabitants themselves conceived and built their dwellings as “peasant palaces,” the legacy of an ancient Egyptian architecture. Benjamin was entranced by this architecture sans architects, by its sobriety, and by the way it bore witness to the relationship between the Ibicencos and their landscape. It was a vernacular style in which, “defying the shadows, the gleaming white of the walls dazzles you.”

And in the main room, chairs of an overwhelming simplicity were always carefully arranged—chairs which, according to Benjamin, “had much to tell.”

Unchanged for centuries, ignored by the rest of Europe, Ibiza began in the thirties to become a focus of interest for travelers and a place of refuge for others. In 1932, however, it was still bypassed by international trade and modernity in general, whose conveniences simply did not exist there. Benjamin had no complaints. For the time being, he enjoyed a kind of contentment enhanced by the splendor of the landscape—the “most untouched” he had ever seen.

Farming and animal husbandry were still “carried on in an archaic manner—there are not more than four cows on the whole island, as the peasants keep to their traditional goats; no agricultural machinery is to be seen and the irrigation of the fields is effected, as it was centuries ago, by means of water scooped up by bucket wheels drawn by mules.”

From his room Benjamin had a view of the sea and of a rocky island illuminated at night by a lighthouse. “It is unfortunately to be feared,” noted Benjamin, “that the construction of a hotel at the port signals the end of all this.”

During this first stay on Ibiza, Benjamin formed a liaison with Olga Parem. They decided to explore the island together and went for long outings on foot and by boat. As soon as he proposed marriage to her, however, she left him.

Three months after his arrival, Benjamin returned to France by way of Majorca. He reached Nice on July 22 and checked in at the Hôtel du Petit Parc. Exhausted, and perhaps depressed by the breakup with Olga, he abruptly decided to take his own life. He drew up a will and sent letters of farewell to his close friends. But he did not proceed. And offered no explanation.

—Translated from the French by Donald Nicholson-Smith

Frédéric Pajak is a Swiss French writer and graphic artist born in Suresnes, France. He has written novels and film scripts, and he is a painter, as was his father, Jacques Pajak. He has edited and contributed to cultural and satirical periodicals and is the editor of the highly illustrated biannual journal Les Cahiers dessinés, devoted to graphic work ranging from cartooning to the drawings of old masters. But Pajak is best known for a long series of books of unique design which present his own full-page drawings accompanied by a biographical and autobiographical quasi narrative. The first of these works, which made his reputation, was L’immense solitude (1999), which won the Prix Michel Dentan in 2000. He followed this with another similarly structured work, Le chagrin d’amour (Broken hearts), which dealt with Guillaume Apollinaire. Later subjects included Joyce, Luther, Freud, Nietzsche, Cesare Pavese, and Schopenhauer. In the same formal vein, Pajak’s ongoing Uncertain Manifesto, which began with the present work in 2012, reached its seventh volume in 2018. The third volume was awarded the Prix Médicis (Essai) in 2014.

Donald Nicholson-Smith’s translations of noir fiction include Jean-Patrick Manchette’s Three to Kill; Thierry Jonquet’s Mygale (a.k.a. Tarantula); and (with Alyson Waters) Yasmina Khadra’s Cousin K. He has also translated works by Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Henri Lefebvre, Raoul Vaneigem, Antonin Artaud, Jean Laplanche, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Guy Debord. For New York Review Books, he has translated Manchette’s Fatale, The Mad and the Bad, Ivory Pearl, and Nada and Jean-Paul Clébert’s Paris Vagabond, as well as the French comics The Green Hand, by Nicole Claveloux, and Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures, by Yvan Alagbé. Born in Manchester, England, he is a longtime resident of New York City.

Excerpted from Uncertain Manifesto, by Frédéric Pajak, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, published by New York Review Books. Copyright © 2012 by Les Éditions Noir sur Blanc, Lausanne. Translation copyright © 2019 by Donald Nicholson-Smith

No comments:

Post a Comment