|

| ‘I thought I had six months to live’ / Self-portrait, November 2020 Tracey Emin after her treatment. Photograph: Courtesy of the Artist |

Tracey Emin on her cancer: 'I will find love. I will have exhibitions. I will enjoy my life. I will'

As she recovers from a brutal summer of cancer treatment, Tracey Emin takes us round her new show – and imagines spending the next 30 years painting in her pyjamas to the sound of birdsong

Stuart JeffriesMonday 9 November 2020

‘I am so lucky,” says Tracey Emin as we stand in the grand galleries of the Royal Academy. I can tell, from her brown eyes, that she’s smiling beneath her face mask. As we roam rooms painted moody blue for her new exhibition, in which her paintings, bronzes and neons are juxtaposed with the oils and watercolours of Edvard Munch, Emin adjusts her stoma bag occasionally and laughs a lot. “I’m in love with Munch,” she says. “Not with the art, but with the man. I have been since I was 18.”

This is not what I expected. Minutes earlier, walking through this London gallery’s courtyard, I felt darkness descending everywhere. England was re-entering lockdown, Biden hadn’t yet won Michigan and the last visitors to the Royal Academy for a month were heading out into the night. I expected the 57-year-old artist to be at death’s door, defeated by disease and circumstance. She is, after all, putting on an exhibition hardly anyone will see: “They sold 16,000 advance tickets but when Boris announced the second lockdown, we knew we couldn’t open.” All she can hope is that the gallery will open in December, but that is uncertain.

Moreover, 2020 seemed set to be Emin’s last year on Earth. “To get past Christmas would be good,” ran the headline earlier this month in the Sunday Times. In June, she was sunning herself naked on the roof of her studio when she noticed her catheter was blood-stained (she’s used a catheter since being treated for appendicitis five years ago, when her bladder stopped functioning and she suffered kidney reflux, pushing urine back into her body). In July, she was admitted to hospital where 12 surgeons worked for six hours to remove a large tumour from her bladder. They cut out her uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, lymph nodes, part of her colon, urethra and some of her vagina. She kept her clitoris, but reflects sadly that it doesn’t work.

‘A sense of fear’ … the artist kept an Instagram diary of her changing moods in lockdown. Photograph: Instagram/White CubeShe blames years of smoking: “Carbon monoxide travels into the bladder. It’s one of the biggest cancer killers, but hardly anybody knows about it.” She has now quit the elite coterie of committed Brit art smokers that includes Maggi Hambling, who never appears in photographs without fag in hand, and David Hockney, who sent Emin a get well card. “When I said I’d given up smoking, he called me a coward. And Maggi’s a hardcore anarchist. I’m not as hardcore as that.” Personally, I doubt that last point.

When Emin says she’s lucky, she means two things. Firstly, she’s luckier than those who died of Covid. “Even when I thought I had six months to live, I was luckier than them. I wasn’t going to die alone – and if it was going to be six months, I at least had time to plan my last days.”

Secondly, for the longest time, she has felt cursed. “I had a friend who said, ‘Terrible things are always happening to you.’ And I thought, ‘Yeah, they really are. It’s like it’s never-ending.’” She was raped twice as a teenager, suffered a miscarriage, had a botched termination, attempted suicide, and lost two of her most renowned works in a fire: her appliqué tent, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995, and her beach hut self-portrait, The Last Thing I Said to You Is Don’t Leave Me Here.

She remembers, at the age of 23, falling out of a boat at night into dark waters. “It was a nice feeling,” she recalls. “That’s what makes you drown. It’s just like going to sleep so you don’t feel anything.” Minutes later, she was on the beach having seawater pumped out of her lungs. “What I’m saying is that’s quite an experience but not like what happened to me in the summer with the cancer. I did feel cursed most of my life and then after this one, when they took my bladder out, I thought, ‘Fucking brilliant! This manky old thing that’s caused me problems all my life has gone.’ And the curse that was like thrown on me has gone with it. It’s in the incinerator. I’m free of that now.” She throws open her arms expansively. “I will find love! I will have exhibitions like this one. I will enjoy my life! I will!”

You look well, I say. “I haven’t had a drink for four months,” she replies, by way of explanation. But there’s more to it than that. “I didn’t have chemotherapy so when people see me, they think I’m completely normal. But I’m still having to recover. I can’t walk that far really. I can’t run. I can’t do a lot of things. It’ll take about six months before I’m better. I am getting better. I have a check-up every two months and a scan because this kind of cancer is so nasty. But yeah, it’s amazing.”

Emin is wearing walking boots beneath a tweed jacket and dress: they look like a hopeful investment in a future that, at one point this year, she didn’t expect to experience. Earlier today, prospective buyers visited her long-time home in Spitalfields, just across the street from Gilbert and George’s house. She’s moving into a Georgian property with huge windows across town in Fitzroy Square. So you’re going posh? “I am! I thought I’d never leave the East End. But this house – the light is amazing. I can imagine painting in my pyjamas and, because it’s pedestrianised, I’ll be able to hear the birdsong.”It feels like a new beginning. “I always thought I’d need a partner. I don’t. I just need myself to be happy. I need myself to do this, nobody else.” Men, she admits, including former lovers Billy Childish, Carl Freedman and Mat Collishaw, helped her artistic development. “Billy made me use oil paints but he also pushed me into realising how to be an artist – in being creative in everything you do and very disciplined.” White Cube gallerist Jay Jopling, discovering Emin was an obsessive letter-writer, encouraged her to do her first text-based works.

But now? She yearns for love, but also wants solitude to paint. There was a time after she graduated from art school when she couldn’t paint. “I was pregnant and the smell made me sick.” And anyway, there was a feeling that painting was ostensibly obsolete. “I never believed that,” she says. “I’ve always loved painting and the love has got deeper as I’ve got older. It’s where I’m happiest.” Fitzroy Square has another advantage. “It’s in hobbling distance of my urologist in Harley Street.” Her new home is also handy for St Pancras station, from where she can get trains to her studio in her beloved hometown of Margate, and to her place in the south of France.

We sit beneath two paintings, Munch’s 1897 Women in Hospital which is dominated by a naked patient, and Emin’s extraordinary picture from 2019, You Kept It Coming, itself dominated by a female figure crawling over a ground of red and a sky of darkling blue. Her assistant, Harry Weller, watched her as she made this picture. “She was crying and screaming,” he says. “And then she would spin around like a whirling dervish.”

“I do paint like that,” she concedes. “I’m lost in a world of love.”Emin spent a lot of time going through the archives at the Munch Museum in Oslo to select works for the show. One day, she pulled out a drawer of watercolours. As a Norwegian curator translated the poem that inspired these works, she found herself crying, her tears very nearly dropping onto the work. “I could have destroyed it! Or made it into the ultimate collaboration.”

Why does she love Munch? “Because he loved women. I used to think he was gay, because his pictures of men are quite sexy and because he lived alone. But the truth is he just treated women well. His housemaids said he was always proper with his models. He didn’t fuck them, unlike lots of artists. Also, he painted great breasts – but vaginas? Hopeless.” Munch often concealed his nude women’s genitals, though whether out of prudishness or because he couldn’t paint them well is uncertain. His painting Puberty is typical: a naked girl, knees together, conceals herself with her arms. Throughout this show, Munch’s nudes are coyly draped below the waist. Emin notes that when Munch does attempt to paint a vagina, he is unconvincing. “They’re in the wrong place!”

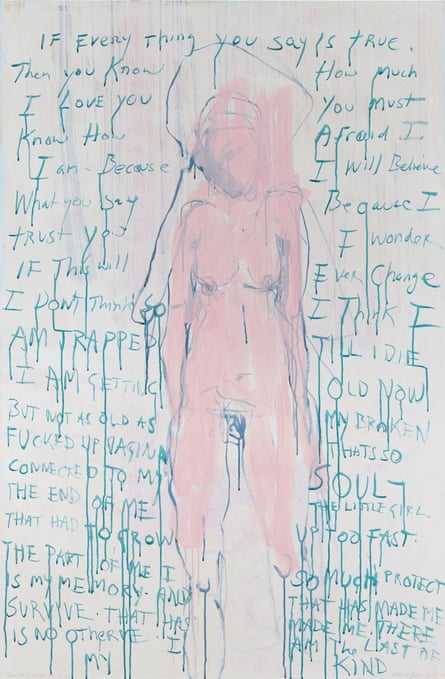

Emin has no such problems. From room to room, blood flows across her canvases, often from between the legs of nudes. “My cunt is wet with fear,” says one neon. In I Am the Last of My Kind, a pink nude is wrapped in text. “I am getting old now,” part of it reads, “but not as old as my broken fucked up vagina that’s so connected to my soul.”

When Emin studied at the Royal College of Art in the 1980s, she was out of temper with the times. Her unfashionable love for Munch and conviction that art should be about expressing often intolerable emotions was symptomatic of a greater disconnection: art was too cold, too intellectual, too rapacious in its gaze for her sensibility. “Picasso was about ‘art’,” she says in a catalogue interview. “Munch wasn’t.” The Norwegian was, rather, about expression. Some of her peers – she cites Peter Doig – dug Munch, but not quite in the way the young Emin did. In 1998, she made a film about Munch, letting out a great long howl at the end while standing on the pier near Oslo where he painted The Scream.

Munch has long been her soulmate, there to take her outside the postmodern art business of filling the world with beguiling commodities to titillate otherwise bored collectors. “Our job as artists is not to make something beautiful,” she says and refuses vehemently the idea that she was ever a Young British Artist. “It was a media tag and meant my work got misunderstood.”

That tag and the perception of her as a YBA ladette contrived to make her seem what she was not: a mere exhibitionist making what Donald Trump lackey Rudy Giuliani dismissed as “sick stuff”. My Bed, her 1998 sculpture, featured used condoms, an apple core, Rizlas, lube, vodka bottles and other detritus, on a crumpled and clearly well used bed. “It was a conceptual work,” she says, “not flaunting my dirty laundry.” Although it did literally include her dirty laundry.

But there’s more going on in Emin’s oeuvre than self-disclosure or uncomfortably honest realism. Art helps Emin submit the mess of life to artistic order. Consider Insomnia, the suite of photographs she took over four years when she was going through the menopause. “I couldn’t sleep so I started taking pictures in my room. Eventually I took one of myself and thought, ‘I look terrible.’ So I tried to take better ones. After a while, I got loads that I thought were really interesting. I wasn’t a victim of something any more, I was doing something.” The world has got less misogynistic in the past 20 years, she reckons. “Earlier in my career, I could have done a piece about periods maybe, but the menopause? Forget it.”

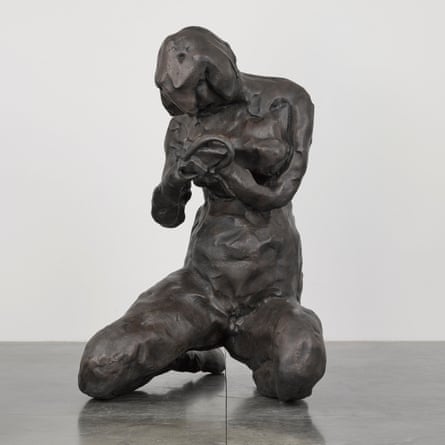

‘Munch never had a mother so I’m giving him one’ … a model for The Mother, Emin’s giant statue to be installed in Oslo harbour by the Munch Museum. Photograph: Tracey Emin, copyright the artistNeither My Bed nor Insomnia will be exhibited in London but both will be shown when the exhibition transfers to Oslo. Missing, too, from the RA show is a bronze sculpture I’d really been looking forward to seeing, just because of its title. There Was So Much More of Me was due to be installed outside the RA’s Burlington Gardens entrance, but roadworks have made that impossible. Shame: I’d love to have seen the crouching Emin’s bronze buttocks enlivening Mayfair. Emin knows that works in the show will be seen in the context of her cancer, but anyone thinking that the title of that sculpture is a reference to her body now would be mistaken. “It’s inevitable,” she says, “ but I did all these works before I got sick.”

Oslo rather than London will also get Emin’s biggest artwork ever: a seven-metre tall bronze called The Mother, depicting her mum Pam who died in 2016. It’s currently being forged in Stoke on Trent and will be installed on Oslo’s Museum Island opposite the Munch Museum. “Munch never had a mother,” she says, “so I’m giving him one.”

Before Emin joins friends and academicians who’ve arrived for a private view, she talks politics. She defends voting for David Cameron. “He legalised gay marriages. His mistake was to think that the British people are kind. He underestimated their stupidity and greed over the EU. But when I voted for him, I got called a Tory cunt. People are horrible.” Leaving the EU was folly, she says. “We need to come together now. You know this,” she says, pointing to her mask, “and this,” she adds, pointing to her stoma bag, “were made in Germany. We won’t get them so quickly now we’re out.”

She thinks Theresa May would have been better at dealing with Covid than Boris Johnson. And she’s exasperated with anyone who thinks the electoral fiasco in the US is democracy in action. “America isn’t a democracy. It may have been once, but now it’s not even a joke. It’s pitiful.”

She heads off to make a speech to her guests. People have been commiserating with her, she says, about the show not opening to the public. “I say, ‘Guess what? I’m going to see it.’” The remark captures Emin’s artistic iconoclasm: showing her work to the public is incidental to what’s really important to her – making art and taking pleasure in the results.

Before we finish the interview, Emin eyes me cheekily and says: “Men only ejaculate once, but women have multiple orgasms.” Excellent, I reply. What are you on about? “Men tend to tail off as they get older. They do their best work between 40 and 50, then they’re done. Women often keep going and do their best work after 50.”

She wants to emulate those women. She sees her life as a trilogy. “When I was 18, I was more honest and had more clarity than I did when I was 35, when I was confused and lost my way. I was a silly twat in some of the things I did – and a lot of the criticism of me was fair. Now I’m in part three. I’m more mature. I’m softer but tougher. I want to project myself into the future and not think about the past. Regret doesn’t help anyone. I’ve got time now, perhaps 30 years. I want to use them to make my best art.”

A couple of days after the interview, Emin rings me. She has been sleeping for a good deal of the time since that private view and our interview. “That’s how remission works,” she says. “Good days and bad days.” She has some good news: that bronze nude There Was So Much More of Me has found a home. It will now be shown from December (lockdown permitting) in a gallery a stone’s throw away from the RA, at White Cube Mason’s Yard. Perhaps she should use the occasion to change the tense of the title: there is so much more to Tracey Emin. And, fingers crossed, in years to come we will get to see it.

Casa de citas / Tracey Emin / Estoy enamorada

Tracey Emin y la cama deshecha

Casa de citas / Tracey Emin / Sexo

Casa de citas / Tracey Emin / Las palabras

DRAGON

My hero / Louise Bourgeois by Tracey Emin

The top 10 self-portraits in art

Tracey Emin / Once called the “enfant terrible” of the Young British Artists

Dorothea Tanning; Tracey Emin review / From the sublime to the miserabilist

Tracey Emin on her cancer / 'I will find love. I will have exhibitions. I will enjoy my life. I will'

Tracey Emin on the Importance of Being a Maverick

Tracey Emin’s My Bed / A Glimpse into the Debased Lifestyle of a Despairing Artist

Tracey Emin and Jeremy Deller Take on Boris and his Brexit

Tracey Emin / Works

A Conversation with Tracey Emin

Tracey Emin to turn Margate studio into a museum for her work when she dies

No comments:

Post a Comment