PERSONA

Review by Susan Sontag

One impulse is to take Bergman’s masterpiece for granted. Since 1960 at least, with the breakthrough into new narrative forms propagated with most notoriety (if not greatest distinction) by Last Year in Marienbad, audiences have continued to be educated by even more elliptical and complex work. As Resnais’ imagination was subsequently to surpass itself in Muriel, a succession of ever more difficult and rewarding films has turned up in recent years. But that good fortune releases nobody who cares about films from acclaiming work as original and triumphant as Persona. It is depressing that the film has thus far received only a fraction of the attention it deserves – at least in New York and Paris. (At the moment of writing, it hasn’t yet opened in London.)

Of course, some of the paltriness of the critics’ reaction may be more a response to the signature Persona carries than to the film itself. That signature has come to mean a prodigal tirelessly productive career; a rather facile, often merely beautiful, by now (it seemed) almost over-size body of work; a lavishly inventive, sensual, yet somewhat melodramatic talent, employed with what appeared to be a certain complacency, and prone to embarrassing displays of intellectual bad taste. From the Fellini of the North, exacting filmgoers could hardly be blamed for not expecting, ever, a truly great film. But Persona happily forces one to put aside such dismissive preconceptions about its author.

The rest of the neglect of Persona may be set down to emotional squeamishness; the film, like much of Bergman’s recent work, bears an almost defiling charge of Personal agony. I’m thinking particularly of The Silence – most accomplished, by far, of the films made before this one. And Persona draws heavily on the themes and schematic cast established in The Silence. (The principal characters in both films are two women bound together in a passionate agonised relationship, one of them the mother of a drastically neglected small boy. Both films take up the themes of the scandal of the erotic, the polarities of violence and powerlessness, reason and unreason, language and silence, the intelligible and the unintelligible.) But the new film ventures at least as much beyond The Silence as the distance separating that film, by its emotional power and subtlety, from Bergman’s entire previous work.

That distance gives, for the present moment, the measure of a work which is undeniably ‘difficult’. Persona is bound to trouble, perplex and frustrate most filmgoers – at least as much as Marienbad did in its day. Or so one would suppose. But, heaping imperturbability upon relative neglect, critical reaction has shied away from associating anything very baffling with the film.

The critics have allowed, mildly, that the latest Bergman is unnecessarily obscure. Some add that this time he’s overdone the mood of unremitting bleakness. It’s intimated that with this film he has ventured out of his depth, exchanging art for artiness. But the difficulties and rewards of Persona are much more formidable than such banal objections would suggest.

Of course, evidence of these difficulties is available anyway. Why else all the discrepancies plain misrepresentations in critics’ accounts of what actually happens during the film? Like Marienbad, Persona seems to be full of obscurity. Its general look has nothing of the built-in, abstract evocativeness of the chateau in Resnais’ film: the space and furnishings of Persona are antiromantic, cool, clinical, and bourgeois modern. But there’s no less of a mystery lodged in this setting. Images and dialogue are given which the viewer cannot help but find puzzling, not being able to decipher whether certain scenes take place in the past, present or future; and whether certain images and episodes belong to ‘reality’ or ‘fantasy’.

One common approach to a film presenting difficulties of this now fairly familiar sort is to declare such distinctions to be irrelevant, and the film to be actually all of one piece. What’s happened is that its action has been situated in a merely (or wholly) ‘mental’ universe. But this approach merely postpones the difficulty, it seems to me. Within the structure of what is shown, the elements continue being related to each other in the ways that might have led the viewer to settle for supposing some events to be ‘real’ and’ others visionary (whether dream, fantasy, hallucination or extra-worldly visitation). For example: causal connections observed in one portion of the film are flouted in another part; several equally persuasive but mutually exclusive explanations are given of the same event. These discordant internal relations are only transposed, intact, when the whole film is relocated in the mind.

Actually, it’s no more helpful to describe Persona as a wholly subjective film, one taking place entirely within someone’s head, than it was (how easy to see that now) in elucidating Marienbad, a film whose disregard for conventional chronology and a clearly delineated border between fantasy and reality could scarcely have constituted more of a provocation than Persona.

What first needs to be made clear about Persona is what can’t be done with it. The most skilful attempt to arrange a single, plausible anecdote out of the film must leave out or contradict some of its key sections, images and procedures. It’s the failure to perceive this critical rule that has led to the flat, impoverished and partly inaccurate account of the film promulgated almost unanimously by reviewers.

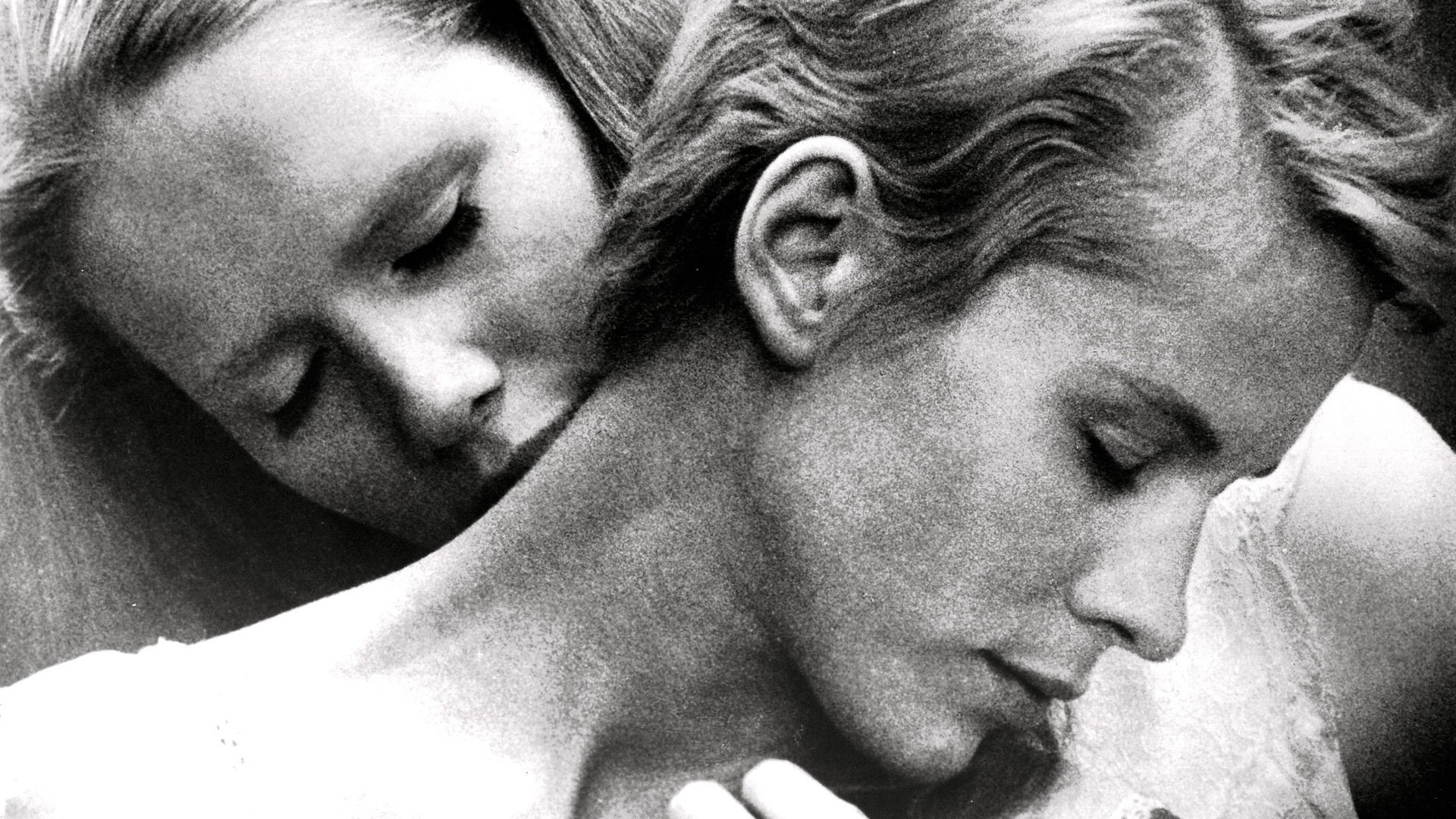

According to this account, Persona tells the story of two women. One is a successful actress, evidently in her mid-thirties, named Elizabeth Vogler (Liv Ullmann), now suffering from an enigmatic mental collapse whose chief symptoms are muteness and a near-catatonic lassitude.

The other is the pretty young nurse of twenty-five named Alma (Bibi Andersson) charged with caring for Elizabeth – first at the mental hospital, then at the beach cottage loaned to them by the woman psychiatrist who is Elizabeth’s doctor and Alma’s supervisor. What happens in the course of the film, according to the critics’ consensus, is that, through some mysterious process, each of the two women becomes the other. The officially stronger one, Alma, gradually assumes the problems and confusions of her patient, while the sick woman, felled by despair and/or psychosis, regains her power of speech and returns to her former life. (The viewer doesn’t see this exchange consummated: what he sees at the end of Persona looks like an agonised stalemate. But it was widely reported that the film, until shortly before it was released, contained a brief closing scene which showed Elizabeth on the stage again, apparently completely recovered. From this, presumably, the viewer was to infer that the nurse is now mute and has taken on the burden of her despair.)

Proceeding from this constructed version, half ‘story’ and half ‘meaning’, critics have read off a number of further meanings. Some regard the transaction between Elizabeth and Alma as illustrating some impersonal law which operates intermittently in human affairs, no ultimate responsibility pertains to either of them. Others posit a conscious cannibalism of the innocent Alma by the actress – and thus read the film as a parable of the predatory energies of the artist, forever scavenging life for ‘material’. Other critics move quickly to an even more general plane, and extract from Persona a diagnosis of the contemporary dissociation of personality, a demonstration of the inevitable failure of good will and trust and predictably correct views on such matters as the alienated affluent society, the nature of madness, psychiatry and its limitations, the American war in Vietnam, the Western legacy of sexual guilt, and the Six Million. (Then they often go on, as Michel Cournot did in Le Nouvel Observateur, to chide Bergman for this vulgar didacticism which they have imputed to him.)

My own view is that, even when turned into a ‘story’, this prevailing account of Personagrossly oversimplifies and misrepresents. True, Alma does seem to grow progressively more vulnerable; in the course of the film she is reduced to fits of hysteria, cruelty, childish dependence and (probably) delusion. It’s also true that Elizabeth gradually becomes stronger, that is, more active, more responsive; though her change is far subtler and, until virtually the end, she still refuses to speak. But all this is hardly tantamount to an ‘exchange’ of attributes and identities. Nor is it established that Alma, however much she does come, with pain and longing, to identify herself with the actress, takes on Elizabeth’s dilemmas, whatever these may be. (They’re far from made clear.)

With Persona, it’s the temptation to invent more ‘story’ that has to be resisted. Take, for instance, the scene which starts with the abrupt presence of a middle-aged man wearing dark glasses (Gunner Bjornstrand) near the beach cottage. All we see is that he approaches Alma, addressing her and continuing to call her, despite her protests, by the name of Elizabeth, that he tries to embrace her; that throughout this scene Elizabeth’s impassive face is never more than a few inches away; that Alma suddenly yields to his embraces, saying “Yes, I am Elizabeth” (Elizabeth is still watching intently), and goes to bed with him amid a torrent of endearments. Then we see the two women together (shortly after?); they are alone, behaving as if nothing has happened.

This sequence can be taken as illustrating Alma’s growing identification with Elizabeth, and gauging the extent of the process by which she is learning (really? in her imagination?) to become Elizabeth. While Elizabeth has voluntarily (?) renounced being an actress, by becoming mute, Alma is involuntarily and painfully engaged in becoming that Elizabeth Vogler, the performer, who no longer exists. Still, nothing we see justifies describing this scene as most critics have done as a ‘real’ event – something that happens in the course of the plot on the same level as the initial removal of the two women to the cottage. But neither can we be absolutely sure that this, or something like it, isn’t taking place. After all, we do see it happening. (And it’s in the nature of cinema to confer on all events, without indications to the contrary, an equivalent degree of reality: everything shown on the screen is ‘there’, present.)

The difficulty is that Bergman withholds the kind of clear signals for sorting out what’s fantasy from what is ‘real’ offered, for example, by Bunuel in Belle de Jour. Bunuel has put the clues there, he wants the viewer to be able to decipher his film. The insufficiency of the clues Bergman has planted must be taken to indicate that he intends the film to remain partly encoded. The viewer can only move towards, but never achieve, certainty about the action. However, so far as the distinction between fantasy and reality has any use in understanding Persona, I should argue that much more than critics have allowed of what happens in and around the beach cottage is most plausibly understood as Alma’s fantasy. One prime piece of evidence is a sequence occurring soon after the two women arrive at the seaside. It’s the sequence in which, after we have seen (i.e., the camera has shown) Elizabeth enter Alma’s room and stand beside her and stroke her hair, we see Alma, pale, troubled, asking Elizabeth the next morning “Did you come to my room last night?” And Elizabeth, slightly quizzical, anxious, shaking her head No.

Now, there seems no reason to doubt Elizabeth’s answer. The viewer isn’t given any evidence of a malevolent plan on her part to undermine Alma’s confidence in her own sanity nor for doubting Elizabeth’s memory or sanity in the ordinary sense. But if that is so, two important points may be taken as established early in the film. One is that Alma is hallucinating – and, presumably, will continue doing so. The other is that hallucinations or visions will appear on the screen with the same rhythms, the same look of objective reality, as something ‘real’. (However, some clues, too complex to describe here are given in the lighting of certain scenes.) And once these points are granted, it seems highly plausible to take at least the scene with Elizabeth’s husband as Alma’s fantasy, as well as several scenes in which there is a charged, trance-like physical contact between the two women.

But even to make any headway sorting out what Alma imagines from what may be taken as really happening is a minor achievement. And it quickly becomes a misleading one, unless subsumed under the larger issue of the form of exposition employed by the film. As I have suggested, Persona is constructed according to a form that resists being reduced to a ‘story’ – say, the story about the relation (however ambiguous and abstract) between two women named Elizabeth and Alma, a patient and a nurse, a star and an ingenue, alma (soul) and persona (mask). The reason is that reduction to a ‘story’ means, in the end, a reduction of Bergman’s film to the single dimension of psychology. Not that the psychological dimension isn’t there. It is. But a correct understanding of Persona must go beyond the psychological point of view.

This seems clear from the fact that Bergman allows the audience to interpret Elizabeth’s mute condition in several ways – as involuntary mental breakdown, and as voluntary moral decision leading either towards self-purification or suicide. But whatever the background of her condition, it is much more in the sheer fact of it than in its causes that Bergman wishes to involve the viewer. In Persona, muteness is first of all a fact with a certain psychic and moral weight, a fact which initiates its own kind of causality upon en ‘other’.

I am inclined to impute a privileged status to the speech the psychiatrist makes to Elizabeth, before she departs with Alma to the cottage. The psychiatrist tells the silent, stony-faced Elizabeth that she has understood her case. She has grasped that Elizabeth wants to be sincere, not to play a role; to make the inner and the outer come together. And that having rejected suicide as a solution, she has decided to be mute. She advises Elizabeth to bide her time, to live her experience through; and at the end of that time, she predicts, the actress will return to the world… But even if one treats this speech as setting forth a privileged view, it would be a mistake to assume that it’s the key to Persona; or even to assume that the psychiatrist’s thesis wholly explains Elizabeth’s condition. (the doctor could be wrong, or at least be simplifying the matter.) By placing this speech early in the film, and by never referring explicitly to this ‘explanation’ again, Bergman has, in effect, both taken account of psychology and dispensed with it. Without indicating that he regards psychological explanation as unimportant, he clearly consigns to a relatively minor place any consideration of the role the actress’s motives have in the action.

In a sense, Persona takes a position beyond psychology. As it does, in an analogous sense, beyond eroticism. The materials of an erotic subject are certainly present, such as the ‘visit’ of Elizabeth’s husband. There is, above all, the connection between the two women themselves which, in its feverish proximity, its caresses, its sheer passionateness (avowed by Alma in word, gesture and fantasy) could hardly fail, it would seem, to suggest a powerful, if largely inhibited, sexual involvement. But in fact, what might be sexual in feeling is largely transposed into something beyond sexuality, beyond eroticism even. The only purely sexual episode is the scene in – which Alma, sitting across the room from Elizabeth, tells the story of the beach orgy. Alma speaks, transfixed, reliving the memory and at the same time consciously delivering up this shameful secret to Elizabeth as her greatest gift of love.

Entirely through discourse, without any recourse to images (through a flashback), a violent sexual atmosphere is generated. But this sexuality has nothing to do with the ‘present’ of the film, and the relationship between the two women.

In this respect, Persona makes a remarkable modification of the structure of The Silence, where the love-hate relationship between the sisters had an unmistakable sexual energy. In Persona, Bergman has achieved a more interesting situation by delicately excising or transcending the possible sexual implications of the tie between the two women. It is a remarkable feat of moral and psychological poise. While maintaining the indeterminacy of the situation Bergman can’t give the impression of evading the issue, and he mustn’t present anything that is psychologically improbable.

The advantages of keeping the psychological aspects indeterminate (while internally credible) are that Bergman can do many other things besides tell a ‘story’. Instead of having a full-blown ‘story’ on his hands, he has something that is in one sense cruder, and in another more abstract: a body of material, a subject. The function of the ‘subject’ or ‘material’ may be as much its opacity, its multiplicity, as the manner in which it yields itself up to being incarnated in a determinate plot. One predictable result of a work constituted along these principles is that the action would appear intermittent, porous shot through with intimations of absence, of what could not be univocally said.

This procedure doesn’t mean that a narration of this type has forfeited ‘sense’. But it does mean that ‘sense’ isn’t necessarily tied to a determinate plot. What is envisaged instead is the possibility of an extended narration composed of events which are not (wholly) explicated, but which are nevertheless possible. The ‘forward’ movement of such a narrative might be measured by reciprocal relations between its parts e.g. displacements – rather than by ordinary realistic (mainly psychological) causality. Often there might exist what could be called a dormant plot. Still, critics have better things to do than ferreting out the story line as if the author had – through mere clumsiness or error or frivolity or lack of craft concealed it. In such narratives, it isn’t a question of a plot that has been mislaid but of one that has been (at least in part) annulled. That intention, whether conscious on the artist’s part or merely implicit in the work, should be taken at face value and respected.

Take the matter of information. One tactic upheld by traditional narrative is to give ‘full’ information, so that the ending of the viewing or reading experience coincides, ideally with full satisfaction of one’s desire to ‘know’, to understand what happened and why. (This is, of course, a highly manipulated quest for knowledge. It’s the business of the artist to convince his audience that what they haven’t learned at the end they can’t know, or shouldn’t care about knowing.) But one of the salient features of new narratives is a deliberate, calculated frustration of the desire to ‘know’. Did anything happen last year at Marienbad? What did become of the girl in L’Avventura? Where is Alma going when she boards a bus alone in one of the final shots of Persona?

Once it is conceived that the desire to ‘know’ may be (in part) systematically thwarted, the old expectations about plotting can no longer hold. At first, it may seem that a plot in the old sense is still there; only it’s being related at an oblique, uncomfortable angle, where vision is obscured. Eventually though it needs to be seen that the plot isn’t there at all in the old sense, and therefore that the point isn’t to tantalise but to involve the audience more directly in other matters, for instance in the very processes of ‘knowing’ and ‘seeing’. (A great precursor of this conception of narration is Flaubert. And the method can be seen in Madame Bovary, in the persistent use of the off-centre detail in description.)

The result of the new narration, then, is a tendency to de-dramatise. In, for example, Journey to Italy or L’Avventura we are told what is ostensibly a story. But it is a story which proceeds by omissions. The audience is being haunted, as it were, by the sense of a lost or absent meaning to which even the artist himself has no access.

The avowal of agnosticism on the artist’s part may look like unseriousness or contempt for the audience. But when the artist declares that he doesn’t ‘know’ any more than the audience knows, what he is saying is that all the meaning resides in the work itself. There is no surplus, nothing ‘behind’ it. Such works seem to lack sense or meaning only to the extent that entrenched critical attitudes have established as a dictum for the narrative arts that meaning resides solely in this surplus of ‘reference’ outside the work – to the ‘real world’ or to the artist’s intention. But this is, at best, an arbitrary ruling. The meaning of a narration is not the same as a paraphrase of the values associated by an ideal audience with the ‘real life’ equivalents or sources of the plot elements, nor with the attitudes projected by the artist towards them. And there are other kinds of narration besides those based on a ‘story’.

For instance, the material can be treated as a thematic resource – from which different, perhaps concurrent, narrative structures can be derived as variations. Once this possibility is consciously entertained, it becomes clear that the formal mandates of such a construction must differ from those of a ‘story’ (or even a set of parallel stories). The difference will probably appear most striking in the treatment of time.

A ‘story’ involves the audience in what happens, how it comes out. The movement is strongly linear, whatever the meanderings and digressions. One moves from A to B, only to look forward to C, whereupon C (if the affair is satisfactorily managed) points one’s interest in the direction of D. Each link in the chain is, so to speak, self-abolishing – since it has served its turn.

But the development of a theme-and-variation narrative is much less linear. The linear movement can’t be altogether suppressed, since the experience of the audience remains a movement in time. But this forward movement can be sharply qualified by a competing retrograde principle, which could take the form, say, of continual backward- and cross-references. Such a work would invite re-experiencing, multiple viewing. It would ask the spectator, ideally, to be able to position himself at several points in the narrative simultaneously. Time may appear in the form of a perpetual present, or as a conundrum in which it’s made impossible to establish exactly the distinction between past, present and future (Marienbad and Robbe-Grillet’s L’mmortelle are fairly pure examples of the latter procedure). In Persona, Bergman uses a mixed approach. The treatment of sequences in the centre of the film seems realistically chronological, while distinctions of ‘before’ and ‘after’ are drastically bleached out, almost indecipherable at the beginning and close of the film.

But despite this more moderate use of the procedure of temporal dislocation, the construction of Persona is best described in terms of the form: variations on a theme. The theme is that of doubling, and the variations are those that follow from its leading possibilities – duplication, inversion, reciprocal exchange, repetition. Once again, it would be a serious misunderstanding to demand to know exactly what happens in Persona; for what is narrated is only deceptively, secondarily, a ‘story’ at all. It’s correct to speak of the film in terms of the fortunes of two characters named Elizabeth and Alma who are engaged in a desperate duel of identities. But it is no less true, or relevant, to treat Persona as what might be misleadingly called an allegory: as relating the duel between two mythical parts of a single ‘person’, the corrupted person who acts (Elizabeth) and the ingenuous soul (Alma) who founders in contact with corruption.

Bergman is not just telling a ‘story’ about the psychic ordeal of two women: he is using that ordeal as a constituent element of his theme. And that theme, for which I’ve used the name of doubling, is no less a formal idea than a psychological one. We know this in two ways. First, by the fact already stressed that Bergman has withheld enough information about the ‘story’ of the two women to make it impossible to determine clearly the main outlines, much less all, of what passes between them. Second, by the fact that he has introduced a number of reflections about the nature of representation (the status of the image, of the word, of action, of the film medium itself). Persona is not just a representation of transactions between the two characters, Alma and Elizabeth, but a meditation on the film which is ‘about’ them.

The most explicit vehicle for this meditation is the opening and closing sequence, in which Bergman tries to create that film as an object: a finite object, a made object, a fragile perishable object, and therefore existing in space as well as time.

Persona begins with darkness. Then two points of light gradually gain in brightness, until we see that they’re the two carbons of the arc lamp; after this, a portion of the leader flashes by. Then follows a suite of rapid images, some barely identifiable – a chase from a slapstick silent film, an erect penis; a nail being hammered into the palm of a hand; a shot from the rear of a stage of a heavily made-up actress declaiming to the footlights and darkness beyond (we see this image soon again and know that it’s Elizabeth playing her last role, that of Electra); the immolation of a Buddhist monk in Vietnam, assorted dead bodies in a morgue. All these images go by very rapidly, mostly too fast to see; but gradually they’re slowing down, as if consenting to adjust to the time in which the viewer can comfortably perceive them. Then follows a final set of images, run off at normal speed. We see a thin, unhealthy-looking boy around eleven lying under a sheet on a hospital cot against the wall of a bare room; the viewer, at first, is bound to associate to the corpses he’s just seen. But the boy stirs, awkwardly kicks off the sheet, puts on a pair of large round glasses, takes out a book and begins to read. Then we see that ahead of him is an indecipherable blur, very faint, but on its way to becoming an image. It’s the face of a beautiful woman. As if in a trance, the boy slowly reaches up and begins to caress it. (The surface he touches suggests a movie screen, but also a portrait and a mirror.)

Who is the boy? It seems easy for most people to say he’s Elizabeth’s son, because we learn later on that she does have a son, and because the face on the screen is the actress’s face. But is it? Although the image is far from clear (this is obviously deliberate) I’m almost sure that Bergman is modulating it from Elizabeth’s face to Alma’s to Elizabeth’s again. And if that is the case, does it change anything about the boy’s identity? Or is his identity, perhaps, something we shouldn’t expect to know?

In any case, the abandoned ‘son’ (if that’s who he is) is never seen again until the close of the film, when again, more briefly, there is a complementary montage of fragmented images, ending with the child again reaching tentatively, caressingly, towards the huge blurry blow-up of the woman’s face. And then Bergman cuts to the shot of the incandescent arc lamp; the carbons fade; the light slowly goes out. The film dies, as it were, before our eyes. It dies as an object or a thing does, declaring itself to tee ‘used up’ and thus virtually outside the volition of the maker.

Any account which leaves out or dismisses as incidental the way Persona begins and ends hasn’t been talking about the film that Bergman made. Far from being extraneous (or pretentious), as many reviewers found it, this so-called ‘frame’ of Persona is, it seems to me, only the most explicit statement of a motif of aesthetic self-reflexiveness that runs through the entire film. This element of self-reflexiveness in the construction of Persona is anything but an arbitrary concern, one superadded to the ‘dramatic’ action. For one thing, it states on the formal level the theme of doubling or duplication-that is present on a psychological level in the transactions between Alma and Elizabeth. The formal ‘doublings’ are the largest extension of the theme which furnishes the material of the film.

Perhaps the most striking episode, in which the formal and psychological resonances of the double theme are played out most starkly, is the monologue in which Alma describes Elizabeth’s relation to her son. This is repeated twice in its entirety, the first time showing Elizabeth’s face as she listens, the second time Alma’s face as she speaks. The sequence closes spectacularly, terrifyingly with the appearance of a double or composite face, half Elizabeth’s and half Alma’s.

Here, in the very strongest terms, Bergman is playing with the paradoxical nature of film – namely, that it always gives us the illusion of having a voyeuristic access to an untempered reality, a neutral view of things as they are. But what contemporary film-makers more and more often propose to show is the process of seeing itself – giving the viewer grounds or evidence for several different ways of seeing the same thing which he may entertain concurrently or successively.

Bergman’s use of this idea here seems to me strikingly original, but the larger intention is certainly a familiar one. In the ways that Bergman made his film self-reflexive, self- regarding, ultimately self-engorging, we should recognise not a private whim but an example of a well- established tendency. For it is precisely the energy for this sort of ‘formalist’ concern with the nature and paradoxes of the medium itself which was unleashed when the 19th century formal structures of ‘plot’ and ‘characters’ were demoted. What is commonly patronised as the overexquisite self-consciousness in contemporary art, leading to a species of auto-cannibalism, can be seen – less pejoratively – as the liberation of new energies of thought and sensibility.

This, for me, is the promise behind the familiar thesis that locates the difference between traditional and so-called new cinema in the altered status of the camera – “the felt presence of the camera,” as Pasolini has said. But Bergman goes out beyond Pasolini’s criterion, inserting into the viewer’s consciousness the felt presence of the film as an object. He does this not only at the beginning and end but in the middle of Persona, when the image – it is a shot of Alma’s horrified face – cracks like a mirror, then burns. When the next scene up immediately begins (again, as if nothing had happened) the a viewer has not only an almost indelible after-image of Alma’s anguish but an added sense of shock, a formal-magical apprehension of the film – as if it had collapsed under the weight of registering such drastic suffering and then had been, as it were, magically reconstituted.

Bergman’s procedure, with the beginning and end of Persona and with this terrifying caesura in the middle, is more complex than the Brechtian strategy of alienating the audience by supplying continual reminders that what they are watching is theatre (i.e., artifice rather than reality).

Rather, It is a statement about the complexity of what can be seen and the way in which, in the end, the deep, unflinching knowledge of anything is destructive. To know (perceive) something intensely is eventually to consume what is known, to use it up, to be forced to move on to other things.

This principle of intensity lies at the heart of Bergman’s sensibility, and determines the specific ways in which he uses the new narrative forms. Anything like the vivacity of Godard, the intellectual innocence of Jules et Jim, the lyricism of Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution and Skolimowski’s Le Depart, is far from Bergman’s range. His work is characterised by its slowness, its deliberateness of pacing, something like the heaviness of Flaubert. And this sensibility makes for the excruciatingly unmodulated quality of Persona (and of The Silencebefore it), a quality only very superficially described as pessimism.

What is emotionally darkest in Bergman’s film is connected particularly with a sub-theme of the main theme of doubling: the contrast between hiding or concealing and showing forth. The Latin word persona means the mask worn by an actor. To be a person, then, is to possess a mask, and in Persona both women wear masks. Elizabeth’s mask is her muteness. Alma’s mask is her health, her optimism, her normal life (she is engaged; she likes and is good at her work). But in the course of the film, both masks crack.

One way of putting this is to say that the violence the actress has done to herself is transferred to Alma. But that’s too simple. Violence and the sense of horror and impotence are, more truly, the residual experiences of consciousness subjected to an ordeal. It isn’t, as I have suggested, that Bergman is pessimistic about the human situation – as if it were a question of certain opinions. It’s that the quality of his sensibility has only one true subject: the depths in which consciousness drowns. If the maintenance of Personality requires the safeguarding of the integrity of masks, and the truth about a person is always the cracking of the mask, then the truth about life as a whole is the shattering of the total facade behind which lies an absolute cruelty.

It is here, I think, that one must locate the ostensibly political allusions in Persona. I do not find Bergman’s references to Vietnam and the Six Million genuinely topical, in the manner of seemingly similar references in Godard’s films. Unlike Godard, Bergman is not an historically oriented film-maker. The TV newsreel of a Buddhist immolating himself, and the famous photograph of the little boy from the Warsaw Ghetto, are for Bergman, above all, images of total violence, of unredeemed cruelty. It’s as images of what cannot be imaginatively encompassed or digested that they occur in Persona and are pondered by Elizabeth – rather than as occasions for right political and moral thoughts. History or politics enters Personaonly in the form of pure violence. Bergman makes an ‘aesthetic’ use of violence – far from ordinary left-liberal propaganda.

His subject is, if you will, the violence of the spirit. If each of the two women violates the other in the course of Persona, they can be said to have at least as profoundly violated themselves. More generally the film itself seems to be violated – to merge out of and descend back into the chaos of ‘cinema’ and film-as-object.

Bergman’s film is profoundly upsetting, at moments terrifying. It relates the horror of the dissolution of personality (Alma crying out to Elizabeth at one point, “I’m not you!”). And it depicts the complementary horror of the theft (whether voluntary or involuntary is left unclear) of personality, what is rendered mythically as vampirism: at one point, Alma sucks Elizabeth’s blood. But it is worth noting that this theme need not necessarily be treated as a horror story. Think of the very different emotional range in which this material is situated in Henry James’ late novel, The Sacred Fount. The vampiristic exchanges between the characters in James’ book, for all their undeniably disagreeable aura, are represented as partly voluntary and, in some obscure way, just. But the realm of justice (in which characters get what they ‘deserve’) is rigorously excluded by Bergman. The spectator isn’t furnished (from some reliable outside point of view) with any idea of the true moral standing of the two women, their enmeshment is a donnee, not the result of some prior situation we are allowed to understand. The mood is one of desperation: all we are shown is a set of compulsions or gravitations, in which they founder, exchanging ‘strength’ and ‘weakness’.

But perhaps the main contrast between Bergman and James on this theme derives from their differing positions with respect to language. As long as discourse continues in the James novel, the texture of the person continues. The continuity of language, of discourse, constitutes a bridge over the abyss of loss of Personality, the foundering of the Personality in absolute despair. But in Persona it is precisely language – its continuity – which is in question.

It might really have been anticipated. Cinema is the natural home of those who don’t trust language, a natural index of the weight of suspicion lodged in the contemporary sensibility against ‘the word’. As the purification of language has been envisaged as the peculiar task of modernist poetry and of prose writers like Stein and Beckett and Robbe-Grillet, so much of the new cinema has become a forum for those wishing to demonstrate the futility and duplicities of language.

In Bergman’s work, the theme had already appeared in The Silence, with the incomprehensible language into which the translator sister descends, unable to communicate with the old porter who attends her when she lies ill, perhaps dying, in the empty hotel in the imaginary garrison city. But Bergman did not take the theme beyond the fairly banal range of the ‘failure of communication’ of the soul isolated and in pain and the ‘silence’ that constitutes abandonment and death. In Persona, the notion of the burden and the failure of language is developed in a much more complex way.

Persona takes the form of a virtual monologue. Besides Alma, there are only two other speaking characters, the psychiatrist and Elizabeth’s husband: they appear very briefly. For most of the film we are with the two women, in isolation at the beach – and only one of them, Alma, is talking, talking shyly but incessantly. Though the verbalisation of the world in which she is engaged always has something uncanny about it, it is at the beginning a wholly generous act, conceived for the benefit of her patient who has withdrawn from speech as some sort of contaminating activity. But the situation begins to change rapidly. The actress’s silence becomes a provocation, a temptation, a trap. For what Bergman shows us is a situation reminiscent of Strindberg’s famous one-act play The Stronger, a duel between two people, one of whom is aggressively silent. And, as in the Strindberg play, the one who talks, who spills her soul, turns out to be weaker than the one who keeps silent. (The quality of that silence is changing all the time, becoming more and more potent: the mute woman keeps changing.) As real gestures – like Alma’s trustful affection – appear, they are voided by Elizabeth’s relentless silence.

Alma is also betrayed by speech itself. Language is presented as an instrument of fraud and cruelty (the blaring newscast; Elizabeth’s cruel letter to the psychiatrist which Alma reads); as an instrument of unmasking (Alma’s excoriating portrait of the secrets of Elizabeth’s motherhood); as an instrument of self-revelation (Alma’s confessional narrative of the beach orgy) and as art and artifice (the lines of Electra that Elizabeth is delivering on stage when she suddenly goes silent; the radio drama Alma turns on in her hospital room that makes the actress smile). What Persona demonstrates is the lack of an appropriate language, a language that’s genuinely full. All that is left is a language of lacunae, befitting a narrative strung along a set of lacunae or gaps in the ‘explanation’. It is these absences of sense or lacunae of speech which become, in Persona, more potent than words while the person who places faith in words is brought down from relative composure and confidence to hysterical anguish.

Here, indeed, is the most powerful instance of the motif of exchange. The actress creates a void by her silence. The nurse, by speaking, falls into it – depleting herself. Sickened almost by the vertigo opened up by the absence of language, Alma at one point begs Elizabeth just to repeat nonsense phrases that she hurls at her. But during all the time at the beach, despite every kind of tact, cajolery and anguished pleading, Elizabeth refuses (obstinately? maliciously? helplessly?) to speak. She has only one lapse. This happens when Alma, in a fury, threatens her with a pot of scalding water. The terrified Elizabeth backs against the wall screaming “No, don’t hurt me!” and for the moment Alma is triumphant. But Elizabeth instantly resumes her silence. The only other time the actress speaks is late in the film – here the time is ambiguous – when in the bare hospital room (again?), Alma is shown bending over her bed, begging her to say just one word. Impassively, Elizabeth complies. The word is ‘Nothing’.

At the end of Persona, mask and person, speech and silence, actor and ‘soul’ remain divided – however parasitically, even vampiristically, they are shown to be intertwined.

Sight and Sound, Autumn 1967

No comments:

Post a Comment