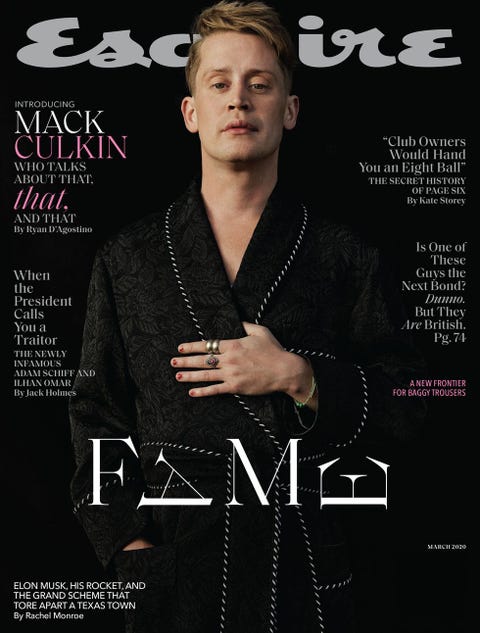

Macaulay Culkin Is Not Like You

The 39-year-old—call him 'Mack'—has been liberated longer than you realize.

BY RYAN D'AGOSTINO

February 11, 2020

He is taking off his pants while standing up, trying not to fall over. He’s got his ankle kind of balanced on the opposite knee, and he sometimes loses his balance for a second, the way you and I do when we take off our pants while standing up. He has to hop on one foot. Sometimes he lets out a little whoop when he teeters on one foot, the way you and I might, especially if six people were watching us take off our pants and we lost our balance.

So there he is in his underwear. Macaulay Culkin.

I don’t know, they were like baggy briefs, I guess. Tan.

He goes by Mack. “Hi, I’m Mack,” he had said four minutes earlier, before I saw him in his underwear.

I’m not sure if I should look away, maybe. But it’s a photo shoot, so he has to keep changing, and he doesn’t appear to care that there are six people he doesn’t know watching him in his underwear. He’s making small talk with the stylist. (“Where’d you grow up?” “Manhattan. Yeah, I’m a city kid.” “Oh, yeah? Manhattan?” “Yep.”)

He sounds . . . normal?

He quickly re-pants, slips a T-shirt over his broad, taut, slightly elongated, pinkish, not-hairy, almost-forty-year-old torso. He slides on a pair of sunglasses with big rims tinted the color of a ripe peach.

He looks good. Healthy. Is that a surprise?

“Goin’ to get a little fresh air,” Mack says, smirking at his use of a cliché. The smirk is a Macaulay Culkin thing: One end of his full mouth curls up to one side in a way that makes him look like he knows something you don’t.

His publicist, a gentle woman who has been his publicist since he was ten years old, two people who connected with each other and haven’t let go, gently hands him his pack of Parliaments and beat-up green drugstore lighter. His fingernails are painted red, and the paint is scuffed. She is expressionless as she hands him the cigarettes, or maybe she chooses not to express how much it worries her every time he puts a cigarette between his lips.

Now he stands in the driveway of a former industrial building where the photo shoot is happening. The smoke break? He checks his phone, to see if his brother wrote back—his brother Kieran just got a Golden Globe nomination, and Mack texted him congratulations. A guy driving a truck rolls down his window and asks for a cigarette, but Mack holds up his pack and crumples it to show the guy it’s empty. Then he calls the restaurant, his regular place, to tell them he’s coming in tomorrow night.

A smoke break.

Back inside the former industrial building, he changes outfits again. The photographer and stylist have him getting into a bright red shirt and a dark black suit and shoes the color of custard. His blond hair is cut high and tight, showing off his ears, which are as you remember them.

“Yeah, this is waaayy better than being home wearing my pajamas,” he says loudly as he buttons the shirt, smirking over at his publicist. “Oh, yeah. Why would I want to be home in my bed right now? With my cats? And my lady? That would be terrrrible.”

In truth, he hasn’t done a photo shoot like this in fifteen years. Which is not to say he hasn’t been a celebrity. Macaulay Culkin has been so famous for so many years that it is pretty much the only life he knows or can remember.

But he was gone for so long. Or seemed gone. A kind of nether-celebrity. What about the stories about Michael Jackson? The drugs—that photograph, when he looked so skinny? Why did he stop making movies?

Is he weird? He’s weird, right?

Before the shot, when no one else is around, he says to me, quietly, “This is not really my cup of tea. These are all lovely people, but the poking, the prodding—honestly, it’s part of why I don’t do this anymore. Any of it.”

And yet here he is, and on the set, when it’s time to pose, he is golden. He awaits instruction, a pillar amid swirling photographer’s assistants and helpers and a groomer and production people. He occasionally warbles along with the radio, but otherwise he says little, stands where he is asked, politely obliges when a different angle of the neck is requested. He positions and repositions his body; says, “Okay” and “Sure” and “Like this?”

He is working.

His eyelids are heavy, same as when he was a kid. When he raises his eyebrows, his eyes pop open and he looks amused. When his lids are low, he looks either bored or hyperfocused—you can’t always tell with Mack, and that’s part of what made him a joy to watch in the dozen movies he did before age fourteen, and especially in Home Alone, the movie that ultimately left him very much alone in the world.

The photographer asks him to lean against the wooden wall, and he does. Then he rests his head against the wall, which makes him look contemplative, but really he’s just posing, because these are the conventions of celebrity: the pose, the hair spray, the fashion credits, the staring into the camera. It’s what celebrities do to promote their next movie, their new song, their comeback.

The thing is, Macaulay Culkin isn’t promoting anything at all. What’s more, he would apparently rather be home with his cats.

So what on earth is he doing here?

“Maaaaack!”

This is the beaming abuelo who co-owns Carlitos Gardel, an Argentine restaurant on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles where Mack has been eating a couple times a month for fifteen years whenever he’s in town. The man embraces Mack like he’s family come home for Sunday supper. His wife—she makes the desserts—comes over for a kiss.

Mack orders a bottle of red wine, the one he likes. Waiters and attendants and family members assure his comfort. A basket of warm bread appears; he gets right into it, dunking a big crust into the Carlitos chimichurri sauce, taking a sip of wine—to Mack, this is all comfortable and easy, these people and this food. The warm relief of the familiar.

Mouth half full, he’s talking about how he’s changing his middle name. It started as a gag on the website he runs, BunnyEars.com, on which readers could vote for what Mack should change his middle name to. He even went on The Tonight Show, and Jimmy Fallon cast his vote. The choices were:

Macaulay Culkin (which would make his legal name Macaulay Macaulay Culkin Culkin);

Kieran (suggested by his brother Kieran);

TheMcRibIsBack (the McRib being back);

Publicity Stunt; and

Shark Week (which Mack has never watched).

The winner, with almost sixty-one thousand votes, was Macaulay Culkin. Mack smiles his I’m-amusing-myself smile the whole time he goes on about it: “I still haven’t officially done it. There’s a lot of hoops you gotta jump through. I have a high-powered, high-priced attorney all over it, and he goes, ‘It’s not as easy as you’d think.’ But yeah, no, it’s happening. This gag is like a year old. I gotta do this.”

I ask if Kieran ever texted back about the Golden Globe nomination. They’re pretty close—Mack flew out to New York to meet Kieran’s new baby last year. Kieran is crushing it on Succession. “I think he did,” Mack says, thumbing his iPhone screen. “I told him, ‘Fuck Winkler, you got this.’ ” (Henry Winkler was nominated for his role on the series Barry.) “And Kieran said, ‘Actually, we’re both gonna get fucked by that hot priest this year. Which sounds more fun than it’ll actually be. But thanks.’ ” (That would be Andrew Scott, from Fleabag. Neither was right: Stellan Skarsgård won.)

The middle-name contest? Mack does stuff like that. Stuff that seems super weird but to him is just fun and amusing. Like the time he joined a cover band that rewrote Velvet Underground songs so that they were all about pizza, and ended up touring with them for a year in 2014. Started as a gag. The Pizza Underground, they were called.

What he doesn’t do is act in movies much anymore, but the movies he did do—in particular that one movie—have allowed him the kind of life where he can do these gags, can even go on The Tonight Show or Joe Rogan anytime he wants, but without the pressure of promoting something all the time. Because the promotion? The promotion just about killed him. “Doing junkets and things—that stuff always drove me crazy,” he says.

Last year, he was brilliant as a half-drunk tour-boat operator in Thailand in a wonderful film called Changeland that his buddy Seth Green made and that Mack had to do zero press for. It was the first movie Green directed, and he wrote it, too, a heartrending buddy dramedy about friends reconnecting on a trip.

But Changeland was, like, his fourth movie in twenty years.

Don’t some actors make movies and just not do all the crap that goes along with it? Couldn’t he do that?

He nods.

“No, it’s true. It’s just—I enjoy acting. I enjoy being on set,” he says. “I don’t enjoy a lot of the other things that come around it. What’s a good analogy. The Shawshank Redemption. The way he gets out of prison is to crawl through a tube of shit, you know? It feels like to get to that kind of freedom, I’d have to crawl through a tube of shit. And you know what? I’ve built a really nice prison for myself. It’s soft. It’s sweet. It smells nice. You know? It’s plush.”

He drinks some wine.

“People assume that I’m crazy, or a kook, or damaged. Weird. Cracked. And up until the last year or two, I haven’t really put myself out there at all. So I can understand that. It’s also like, Okay, everybody, stop acting so freaking shocked that I’m relatively well-adjusted. Look: I’m a pretty peerless person. If I was an accountant, I could look left and right, and there’s other accountants sitting next to me in the office. It’s not like that. It’s one of those things where, like, the cliché that we’re all snowflakes? That we’re all unique? Well, you know what?” Mack leans in real close, drops his voice, looks me dead in the eye, and says, with a smile I haven’t seen since the last time I watched Home Alone and Kevin McCallister smiled directly into the camera, “I actually am a snowflake.”

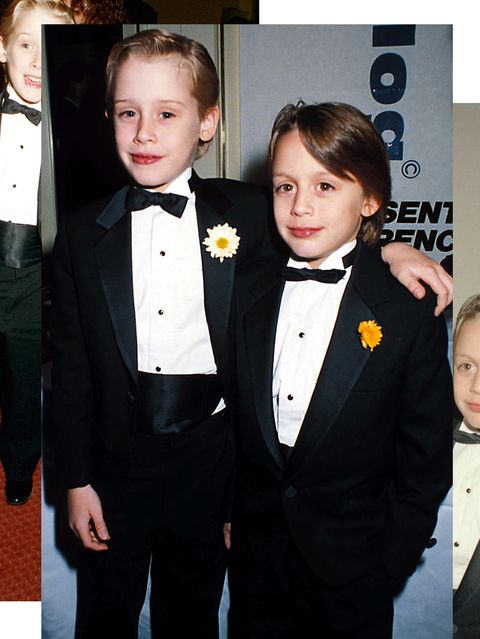

The Macaulay Culkin origin story usually starts with the bad dad. Why even name him here? Bullying failed actor shoves his offspring into the business using shame and threats—that was it. There were seven kids and two parents crammed into a one-bedroom on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. He enrolled Mack in classical ballet and signed him up for the Ensemble Studio Theatre, a respected company.

With Mack, of course, the dad thought he had hit it big. At eight, Mack was cast in a movie, Rocket Gibraltar, with Burt Lancaster and a bunch of prefame New York theater actors, including Bill Pullman, Patricia Clarkson, and Kevin Spacey, who was, like Mack, appearing in his first big movie. (Me: “I thought Kevin Spacey was really funny in that movie.” Mack, loud and sarcastically: “He’s hilarious now!”)

We’re talking about this at Carlitos, where dinner rolls along the way he is used to: a plate of grilled blood sausage, a Mack favorite; plump green gnocchi, the leftovers of which he will take home to the woman he calls “my lady.”

A year after Rocket Gibraltar, Mack got a role in the John Hughes comedy Uncle Buck. In one scene, a woman arrives at the front door and he peers through the mail slot. “That scene where I’m looking through the mail slot? Hughes saw that and he got the idea: Kid defends house! And he wrote Home Alone for me,” Mack says.

From there, he became the hardest-working human in show business—and it wasn’t so bad at first. “I was enjoying it at that point,” he says, washing down a garlicky shrimp with some wine. “I was a bit of an attention whore. ‘Hey, I’m a kid, look at me!’ But I was not tugging on my mother’s or father’s sleeve saying, ‘Mommy, Daddy, I want to be a thespian.’ I enjoyed it because I was good at it and I knew it. I was at least sharp enough to understand good attention.”

No Culkin would truly understand the humongousness of Home Alone for some time. Mack’s youngest sibling, his brother Rory, was born a year before the movie came out. “It wasn’t until my classmates in the first grade were telling me about my own brother that I realized, Oh, everyone knows him. Wait, is he everyone’s brother? I don’t get it,” Rory says. “And I guess in a sense, he was.”

Still, the father started leveraging it immediately, making the decisions as Mack became a money-making machine. Some turned out well: My Girl, Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, The Good Son(a messed-up movie worth rewatching). But there was also Only the Lonely(not John Candy’s best), a TV cartoon series that ran for one season, Getting Even with Dad (a forgettable Ted Danson vehicle), The Pagemaster (a partly animated flop), and Richie Rich, in which you can actually read on Mack’s bloodless face, normally so malleable and expressive, how much he doesn’t want to be doing this.

“It started feeling like a chore. I started vocalizing that and not being heard: I was saying, ‘I wanna go to school—I haven’t done a full year of school since first grade,’ ” he says.

The truth was, everyone knew Macaulay Culkin, but Macaulay Culkin felt like he didn’t know anyone.

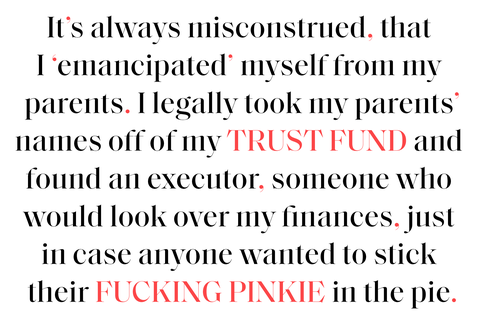

Mack’s parents were never legally married, so when they split up in his mid-teens, it wasn’t a divorce. A custody fight over the children dragged on for two years. Also at stake was Mack’s trust fund—his earnings were reported to be $15 million to $20 million. “We didn’t want to go with my father,” Mack says. “It’s always misconstrued, that I ‘emancipated’ myself from my parents. I legally took my parents’ names off of my trust fund and found an executor, someone who would look over my finances, just in case anyone wanted to stick their fucking pinkie in the pie. But the next thing you know, the story was that I divorced my parents. I just thought I was doing it cleanly—taking my father’s name off, taking my mom’s name off, so my opinion is unbiased. And when I did that, the whole thing kinda ended a lot faster.”

Through all of this, he eats—the gnocchi, the shrimp, and the blood sausage have been decimated. Mack dabs his lips, stands, as if getting up from his own kitchen table, and walks slowly out the front door. On the sidewalk: a glass two-top, with a chunky glass ashtray on it, and two chairs. Fresh air.

He sits, lights up.

“Look, I mean, it sucks,” he says, puffing at the traffic on Melrose. Then he turns, elbows on the table, both hands up by his head. “But: It coulda been worse, you know? I wasn’t working in a coal mine. I wasn’t a child soldier. My father was not sexually abusing me. Certain fucked-up things happened, but fucked-up things happen to kids all the time and they don’t come out the other end. I’ve got something to show for it, man. I mean, look at me: I got money, I got fame, I got a beautiful girlfriend and a beautiful house and beautiful animals. It took me a long time to get to that place, and I had to have that conversation with myself and go, like, Honestly, Mack? It’s not so bad. I want for nothing and need for even less. I’m good, man.”

He stamps out his cigarette, smiles, and says, “He’s a shitty guy, don’t get me wrong.” Then he half stands, and motions with his thumb to go back inside. Back to the warm and familiar womb of Carlitos.

Last night after the photo shoot, at 3:00 a.m., Mack ordered eggs and bacon on Postmates, plus banana pancakes for his girlfriend, Brenda Song, for when she woke up and he was still sleeping.

“I feed my lady,” he says.

She feeds him, too. When he did wake up, around 10:30, he ate a big hunk of garlic rosemary bread she had made. “As fresh as fuck” it was.

Brenda has acted steadily for twenty-five years in everything from The Suite Life of Zack & Cody to Scandal to Dollface, the recent Hulu comedy in which she stars. Last year, she starred in the movie Secret Obsession, which was streamed by 40 million viewers, making it one of the top ten most-watched Netflix originals. She also costarred in Changeland, which is how they got together. (“I didn’t see that one coming,” says Green, who cast them.)

They have two cats—Apples and Dude—and a fish named Cinnamon. (“I tend to name all the animals as if I was a five-year-old,” Mack says.) They have a Shiba Inu, Panda. And they have a bird, a blue-headed pionus, a relatively quiet species of parrot, that was named Nacho when Andy Richter had it for ten years but that Mack calls Macho.

He’s pushing forty—he’s thirty-nine until August—and he’s feeling it in his back, among other places. (“I got an ulcer or two I gotta deal with,” he says. “I don’t poop like I used to. My body’s like, Oh, is this what the beginnings of dying feel like?”) He and Brenda are trying to have a baby. “We practice a lot,” he says, again with the smirk—he knows he’s using another cliché, and he thinks that’s funny. “We’re figuring it out, making the timing work. Because nothing turns you on more than when your lady comes into the room and says, ‘Honey, I’m ovulating.’ ”

Sometimes, late at night, he plays video games—“when I’m stressed, or just for fun. I’m regressing in my video-game playing. Now I’m literally back to playing WrestleMania 2000. Gimme another week and I’ll be playing Pong on an Atari 2600.” And he watches YouTube. He loves The Venture Bros., the animated series on Adult Swim, and Nathan for You, the satire of an Apprentice-type reality show that’s the ball and the biscuit.

Mack has certain phrases he says. Like “the ball and the biscuit.” Lizzo is the ball and the biscuit. The movie Saved!—a satire about a Christian high school, and “the first time I really did a gig where I was surrounded by people my own age, if you think about it”—was the ball and the biscuit.

Mack also spends about three days a week on Bunny Ears, which he started in late 2017. It now employs five full-time staffers as well as twenty-five regular freelancers. They create daily content, plus a weekly podcast, merchandise, and a video channel. He presides over editorial meetings, green-lighting ideas. He crafts headlines for stories. It’s fun and amusing. He cracks himself up. His writers crack him up. He writes about professional wrestling, one of his favorite pastimes. He looks at the finances, which don’t always add up—he is funding the thing, after all.

He has described Bunny Ears as a cross between Goop, Gwyneth Paltrow’s new-agey wellness company, and The Onion, the humor website. It makes fun of self-help, and it also makes fun of the Internet itself, with headlines overtly designed to get traffic from people’s search terms. If you Google “macaulay culkin net worth,” as many people apparently do, one of the top results is a Bunny Ears story titled “Why Macaulay Culkin Isn’t Concerned About His Net Worth.” (It’s about a butterfly net.)

Other Bunny Ears headlines: “Deep Breathing Exercises for When Your Home Is Getting Robbed Right Now,” “Macaulay Culkin Ranks His Favorite Macaulay Culkin Movies,” and “Romantic Mixtape Songs That Say ‘I Wanna Do Butt Stuff.’ ”

Mack has recorded about a hundred episodes of his podcast. (“I wanted to start a podcast, I guess? I don’t know, everyone’s doing it, but it’s not even that—if anything, that makes me notwant to do it. Yeah, but why the hell not? Let me talk. I’m good at talking.”) It’s an extraordinary trove of Macaulay Culkin. For a while in season 1, there was a recurring joke that when he introduced himself at the top of each episode, he never said his real name but instead made fun of the way people always screw it up (“Hi, everyone, this is Makalay McClucklin”. . . “Hey, it’s Mulcahy Cluckster”. . . “I’m McClargy Conklin”). Nor did he ever mention his most famous movie, instead citing The Pagemaster as his claim to fame (“I’m former Pagemaster Makalaka Cuckler”).

Or he might be introduced as “the kid from Home Alone 3,” which he was not in.

So there’s that, the podcast. Otherwise, Mack waters the plants in the backyard and feeds all the animals. He paints. He writes ideas in notebooks piled high.

Home is where Mack is these days. “Yeah, I’m a homebody,” he says. It’s where these two former child stars, one still working as much as she can, the other not so sure, just want to be. With each other, doing whatever.

“People don’t realize how incredibly kind and loyal and sweet and smart he is,” Brenda says. “Truly what makes Mack so special is that he is so unapologetically Mack. He knows who he is, and he’s 100 percent okay with that. And that to me is an incredibly sexy quality. He’s worked really hard to be the person he is.”

She keeps a notebook by her bedside, an old Moleskine that he has drawn in and customized. She writes his one-liners in it, stuff he says in the middle of the night that cracks her up.

Brenda works steadily. She travels. She hustles. But here’s the thing: They bought this house, and that’s significant. For Mack? Yes. A home. He’s been a “tramp,” to use his word. A “vagabond.”

Mack worried that when they started dating, Brenda might have thought he was still in that world—touring with a weird band, hopping into cars with strangers, playing handball in his apartment late at night. He is not that person anymore, of course.

At night, he holds Brenda in their bed, in the fluffy comforters and matching pillows she picked out, their fluffy cats lolling around, legs hanging off the bed, purring. Mack holds Brenda, and he says, “I’m here. I’m right here.”

At Carlitos, the flesh of the branzino is picked apart, white flecks amid shards of bones, the eyes staring up at Mack. Across the table, torn rib-eye in a slick of oil and butter. Wineglasses with oily lip marks around the rims. The lights are low now, the street dark outside. There’s a guy playing the accordion two feet from us.

We were talking about Saved!, the religion movie, and I ask Mack when the last time he went to church was.

“Last time I went to church was my sister’s funeral,” he says. Bobs his head a little, swallows. “So it was about eleven years ago.”

I look down at the table.

Mack’s sister Dakota, the second of the seven Culkin kids, a year older than Mack, was hit by a car in Los Angeles and died the next day, on December 10, 2008.

“She passed away eleven years ago tomorrow.”

He bobs his head a little more.

“Tonight”—eleven years ago tonight—“was the last time I talked to her, and she passed away overnight, kinda thing.”

He stops talking, just for a second, then: “She had a roommate at the time. She said, ‘We just watched Party Monster, and we wanted to compliment you.’ She said, ‘I want you to stay focused and enthused.’ I was like, ‘Thanks. You too. Go to sleep.’ And then she went out to go get some Gatorade and cigarettes, and she got hit by a car.”

His eyebrows lift, but his eyes are slits of contemplation.

“I mean, look, I had that last conversation with her, and she told me to stay focused and enthused.”

Mack sits back, looks around the restaurant. Takes a slug of wine. When he talks again, his tone is Hey, you know, what are ya gonna do?

“Her favorite drink was Budweiser,” he says, the smile returning. “So I’m gonna drink some Budweisers tomorrow. And listen, I’m not gonna get into it. But it’s my day, when I mourn my sister. So yeah.”

Some silence hangs. The accordion player stares with a quiet intensity at his instrument as the music fills the air with some kind of mood, like the sadness of carnivals.

“Yeah.”

When he first started dating Brenda, the feeling that it was too good to be true almost overwhelmed him, almost overwhelmed their very relationship. He was, he says, waiting for the other shoe to drop. “And it’s always gonna drop,” he says. “Something bad’s gonna happen. Someone’s gonna die!”

John Hughes was special to Mack. Even fatherly, though he doesn’t like to use that word. When Mack was filming Richie Rich in Chicago, Hughes stopped by the set and said hello. Mack was physically tired, missed home, and felt uninspired by the movie he was in. (He didn’t make another movie for nine years.) A couple days later, Hughes called him to ask: Are you all right?

It hit Mack even then, as a child: It was the first time anyone had ever asked him that. In a professional capacity—whether he was all right. It was the last time he and Hughes ever spoke.

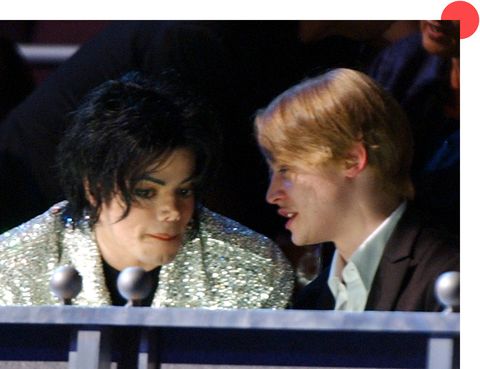

A month before Hughes died, in 2009, Michael Jackson died after being given an overdose of medication. If Hughes sometimes played the father Mack’s father couldn’t be, Jackson was often the schoolmate he never had. Jackson got in touch with Mack after Home Alone, and suddenly they were hanging out. His parents neither encouraged nor discouraged the friendship. The way Mack sees it, Michael had a similar childhood, which is to say that he didn’t really have one, because his father was forcing fame upon him. So, at twenty-two years older than Mack, living in a place called Neverland, he felt the same age, in a way.

Mack and Jackson used to prank-call people. Jackson used to do these voices, real nerdy—“Hello, I’d like to buy a refrigerator. How big are your refrigerators?” And Mack would laugh and laugh.

The last time Mack saw him was in the men’s room at the Santa Barbara County Superior Courthouse in 2005. Mack was twenty-four. Michael was forty-six. Mack was testifying in Jackson’s defense in People v. Michael Jackson, in which the singer was charged with intoxicating and molesting a thirteen-year-old boy who had cancer. He was eventually acquitted.

There was a short recess during Mack’s testimony. Mack took a leak, and Michael came in. Jackson said, “We better not talk. I don’t want to influence your testimony.” They laughed a little at this. Michael Jackson, who had been more famous perhaps even than Macaulay Culkin when he was eight, ten, eleven years old, looked whipped. Exhausted. Drained.

They hugged.

I ask Mack if he is bothered that people assume—because he was one of many boys who spent time at Jackson’s home, some of whom accused him of heinous acts of sexual abuse—Jackson must have abused him, too.

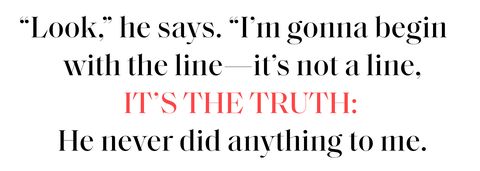

“Look,” he says. “I’m gonna begin with the line—it’s not a line, it’s the truth: He never did anything to me. I never saw him do anything. And especially at this flash point in time, I’d have no reason to hold anything back. The guy has passed on. If anything—I’m not gonna say it would be stylish or anything like that, but right now is a good time to speak up. And if I had something to speak up about, I would totally do it. But no, I never saw anything; he never did anything.

“Here’s a good Michael Jackson story that doesn’t involve Michael Jackson at all: I ran into James Franco on a plane. I’d bumped into him two or three times over the years. I give him a little nod as we’re putting our bags overhead. Hey, how you doing? Good, how ya doing? And it was right after the Leaving Neverland documentary came out, and he goes, ‘So, that documentary!’ And that was all he said. I was like, ‘Uh-huh.’ Silence. So then he goes, ‘So what do you think?’ And I turned to him and I go, ‘Do you wanna talk about your dead friend?’ And he sheepishly went, ‘No, I don’t.’ So I said, ‘Cool, man, it was nice to see you.’ ”

Mack is godfather to Michael’s daughter, Paris, and they remain close. The next thing he tells me is that he has passed along to her his quirky habit of stealing spoons—from restaurants, from cafés, from airplanes. “It’s harmless,” he says. “It’s a harmless thing. It’s not like you’re ruining something, like stealing a chess piece, where the board would be incomplete.”

He and Paris give each other spoons. They have matching spoon tattoos on their inner forearms—Mack’s only tattoo, one of many for Paris. When she was starting to put herself out into the world in a public way, he gave her some godfatherly advice, vis-à-vis the spoons: “Don’t forget to be silly, don’t forget to take something away from this whole experience, and don’t forget to stick something up your sleeve.”

Macaulay Culkin has decided to stay just famous enough that he has options. He can make a movie once in a while if he wants to, and he can have a podcast.

“It’s nice to see Mack out there doing stuff, and not getting caught by paparazzi looking hungover one particular day,” says his friend Har Mar Superstar, a performer who toured alongside the Pizza Underground. “We all have rough moments, but he was under a microscope. People love to see a child star fail for some reason. But now people know he’s alive and has opinions and has a good heart and isn’t some dark character that people want to create.”Brenda hopes that Mack will get back into his profession for real. “I truly believe that he is the actor he is now because of all the things he had to go through,” she says. “He has gone through so much tragedy; he’s had so many ups, so many downs; he’s seen the ugly side of this industry; he’s also seen the amazing side of this industry. So he can pinpoint exactly what he doesn’t want and what he doesn’t like about it. But yeah, I hope, I hope, I hope.”

Toward the end of Changeland, there’s an extended scene of Mack’s character in a boxing match. He has almost no lines, and yet he makes your heart break for this guy, this American lost in Thailand, losing a tourist-trap fight. Green, the director, says, “It was Mack going through that choreography dozens of times. Full speed, taking hits, throwing hits—there was no real way to fake it. He wouldn’t take a photo double. He’s like, Nah, man. You gotta see my face; otherwise, it’s not gonna work.”He auditioned for Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood, the Quentin Tarantino movie from last year. The audition did not go well. Actually: “It was a disaster. I wouldn’t have hired me. I’m terrible at auditioning anyway, and this was my first audition in like eight years.”

Mack published a book when he was twenty-five, and in it he writes pretty clearly about why he soured on acting in the first place. The book is a trip. On the cover it says it’s “A Novel,” but those words are crossed out and the word “Not” is written. It’s called Junior.He told me it’s basically about him. The first chapter is about a monkey boy in the circus, which is essentially Mack being a child star.

I ask him about a line in the book that points out the difference between having fun and being happy.

“Believe me, I would know,” he says. “I’ve had a lot of fun without being happy. And I’ve been happy without necessarily having fun. But also: You can have it all. Just don’t confuse the two. Because it’s easy to! A lot of times, when you’re having fun you’re rolling on MDMA or something.” He laughs a little at this. “It doesn’t mean you’re happy. It just means you’re altered.” He laughs a little harder at this. “One of my favorite jokes: I’ve been accused of having a drug problem, but nothing could be further from the truth. Drugs are the easiest thing I’ve ever done in my life.” He cracks up at this.

But, really, how bad did it get with drugs?

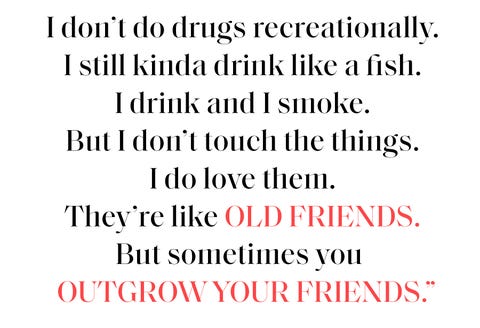

“Um? Listen,” he says, “I played with some fire, I guess is the best way to put it. At the same time, I’ve never been to rehab or anything like that. I’ve never had to clean out that way. There were certain times when I had to catch myself, once or twice. You’re having too good a time, Mack. I mean, I’ve had friends who ask me, ‘How do I get clean?’ And I go, I’m the last person you should ask, because I’m gonna give you the worst advice, which is: Just stop. Just stop! And that’s not the way it works. But I never went so far down that road where I needed outside help. I wouldn’t be the person I am today if I hadn’t had drugs in my life at some point or another. I had some illuminating experiences—but also it’s fuckin’ stupid, too, you know? So besides the occasional muscle relaxer, no, I don’t do drugs recreationally. I still kinda drink like a fish. I drink and I smoke. But I don’t touch the things. I do love them. They’re like old friends. But sometimes you outgrow your friends.”

And here he pauses for a moment. That’s all he’s got to say about that. His thoughts return to his home, which is filled with all kinds of things he never had much of. Cats. Space. A yard. Food in the fridge. Routine. Comfort.

“You know what I’m going to do after this? I’m gonna take care of my back—I’m gonna take a hot bath. I have a video queued up: the history of Castlevania, the Nintendo game. It’s fifty-five minutes long, and that’s the perfect bathtime amount of time. I’m gonna stretch my back out, kiss my animals, and go to sleep with my lady. I’m a man of really simple pleasures.”

The last setup of the shoot was on the roof of the former industrial building. The fire marshal came in and gave us all a speech about being careful up there, and Mack stood listening, dutifully, looking studious almost, arms folded. He thanked Inspector Matthews politely.

He stood on the roof. This was work for Mack, don’t forget. And the fucking clothing guy kept primping and poking and puffing him. Hell of a guy, very sweet guy, but Jay-zus! Mack hasn’t moved a muscle, and the guy’s right back in there, flicking his lapels, straightening his cuffs.

Sweet guy, but. Driving Mack nuts.

After they get the shot, Mack climbs back down the stairs to the main floor. At this point he is wearing another ridiculous costume: an expensive tank top, black suit pants, and white shoes reminiscent of those worn by the Lollipop Guild. (They’re cool, it must be said.) His publicist is walking next to him—they are a team, striding through the former industrial building. The shoot is done.

“Okay?” she asks.

“Yes!” Mack says. “Okay. I’ve decided I’m gonna do the photo shoot!”

So I have to ask him: Why? I mean, it’s great to see him working, even to see him doing the professional-celebrity thing. But it’s so unweird that, after all this time, it’s kind of weird. It’s not like he has a movie coming out anytime soon. And he ain’t exactly hitting the media circuit for Bunny Ears. Mack isn’t really doing anything more than he’s been doing for a while now: keeping the animals alive and keeping his lady fed and, God willing, bringing a child into the world.

So why bother?

He doesn’t hesitate.

“No matter how much I act like a curmudgeonly old man, it’s still fun to get back in the saddle once in a while and play around. The stars aligned, and actually I thought it could be super fun. It’s cool. It’s classy. Nobody had to twist my arm, put it that way. It was a good time, the pictures look great, it made my lady happy. . . . It’s fun. But no, I’m not promoting anything. I’m not even promoting myself. It’s just another little adventure.”

Later that night, when he got home from the shoot, he showed Brenda a couple of the photos from the day that he’d saved on his phone.

She loved them.

No comments:

Post a Comment