In this interview with MFA nonfiction candidate Grace Ann Leadbeater,

Leanne Shapton talks about her upcoming book,

Guestbook: Ghost Stories, out March 26, 2019. Shapton is an artist, author, and publisher. Her book

Swimming Studies won the 2012 National Book Critic’s Circle Award for autobiography, and was long listed for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year 2012. She is also a partner in

J&L Books.

Grace Ann Leadbeater

February 28, 2019

Guestbook investigates what haunts us. What first drew you to explore this idea of being haunted by objects, experiences, people, et cetera?

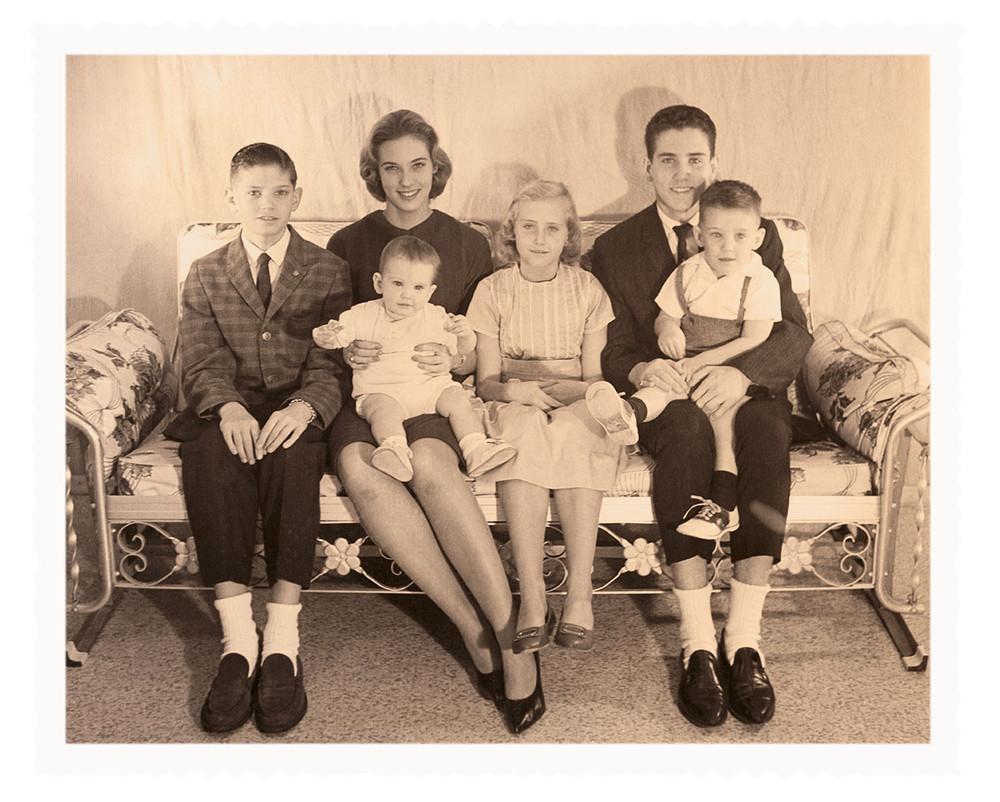

I’ve been interested in old things all my life. I grew up in an old house, my father collected Studebakers. He was an industrial designer and we were surrounded by things from different decades. My mother is Filipino and the house was full of baskets and cups and objects from the Philippines. I’ve always valued and understood that there were stories and meaning in things— sentimental value, design value, and history.

In all of my work I’m looking backwards, whether it’s the book Was She Pretty?, and how we think of our lover’s exes— or Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry. That was a love story in the form of an auction catalog: the objects act as containers, transmitters for storytelling. For The Native Trees of Canada, I took inspiration from a vintage book from 1979— a forestry manual. I’m always looking for how the past resonates or speaks to me now.

The book is bursting with images. Did you ever consider this book existing without images or were the images always a vital part?

They were always a vital part. I’ve read ghost stories and loved ghost stories since I was small. All of my favorite stories are ghost stories, even if they’re not always called ghost stories, like Hamlet, “The Dead,” A Christmas Carol. I love literary ghost stories like Edith Wharton’s “Afterward,” or local lore you might find in a gift shop like Ghost stories of Montana.

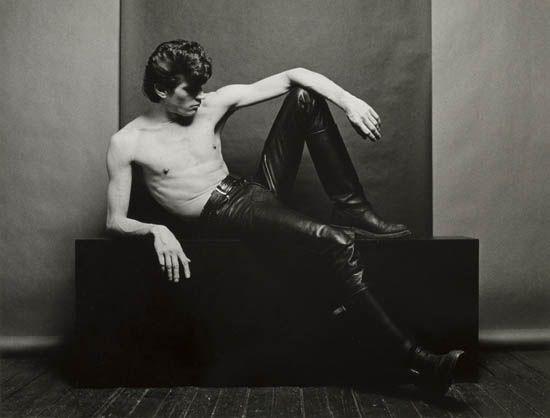

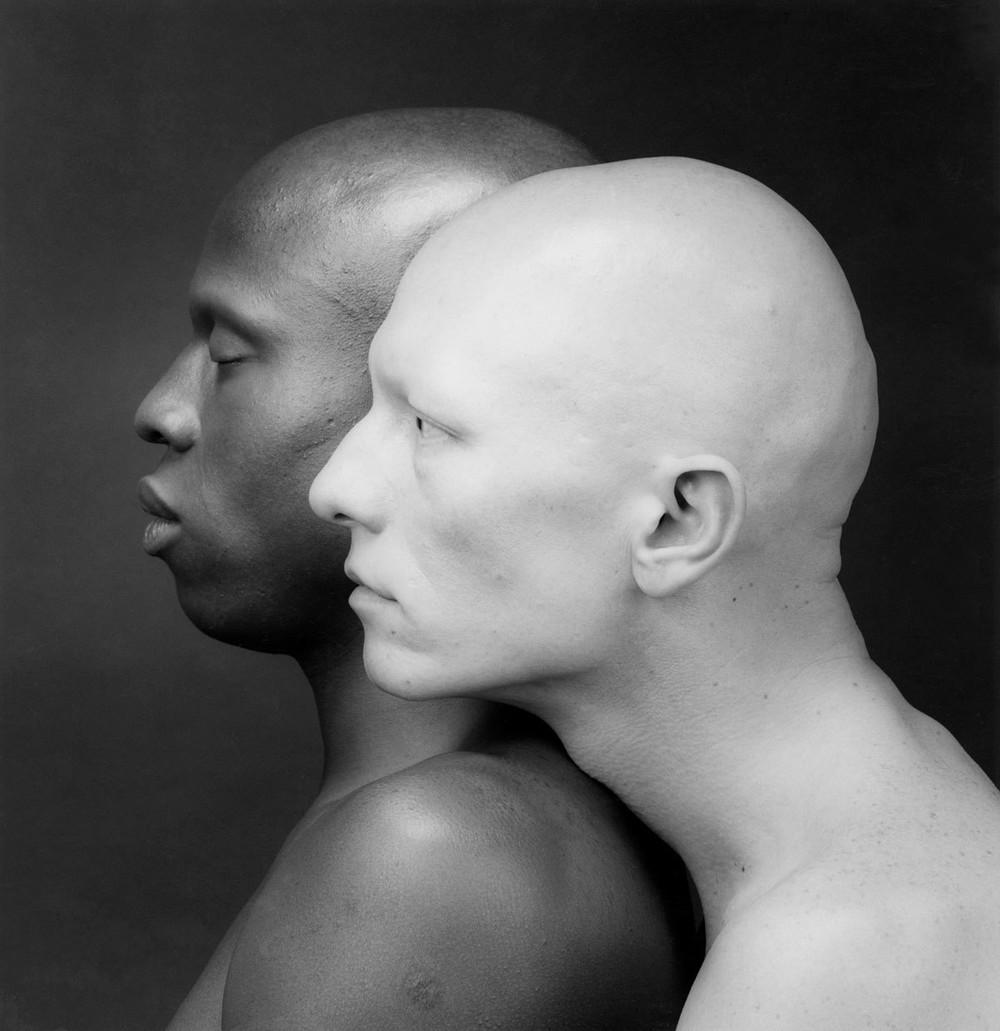

I wanted to do something with the form that involved images. Images carry emotion. In this image-driven culture, they influence what we’re haunted by. Look at Instagram, for example, how violent it can be in terms of inspiring jealousy, sympathy, or making us feel lousy or good about ourselves.

I wanted to see if the ghost story form could carry more or do more with images. Early on in thinking about this book I went to the ghost story section of the London Library. There were all these books by eccentric British ghost hunters, like Borley Rectory: The most haunted house in England. The photographs in those books— often banal images of houses and plain rooms— had terrifically dramatic captions. I loved how that discrepancy worked. The way we looked at those pictures with leading captions could direct comprehension and tone. I could work on emotion more efficiently with a picture.

This collecting of images and artifacts is so exciting in the literary realm. Are these images and artifacts you’ve been collecting for years? Did you go looking for any in the midst of making the book?

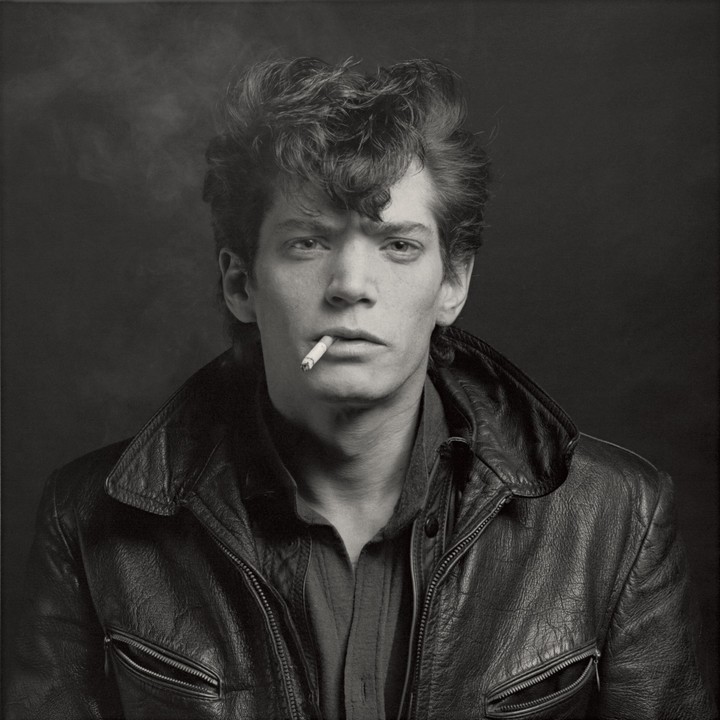

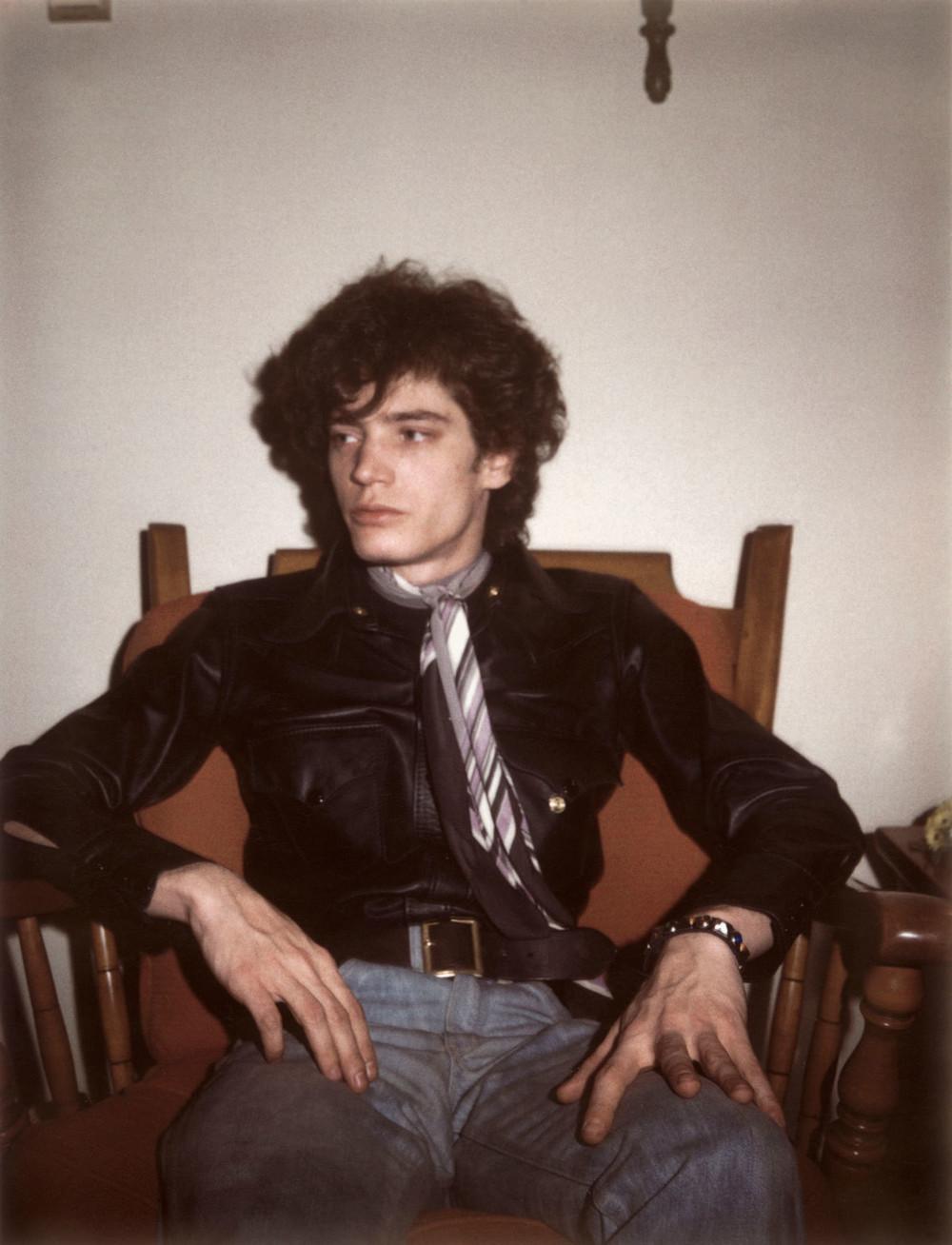

I found most of the images while making the book. I knew that after Important Artifacts I could cast and shoot scenes if I wanted to. But with thirty stories I realized it would get expensive. I turned to my family’s photo albums, my own collection of snapshots, to eBay and Etsy.

With “Eidolon,” the images began as screen grabs from Death in Venice. They then became painted stills from one scene, to abstract them even more. The painted photographs allow one more layer of abstraction—less veracity and more of a floaty quality.

How do you position yourself with the title? Are you a guest studying this guestbook or is it your guestbook that others are the guest of?

The book is full of ghosts that are guests. The epigraph “A geist, A gust, A ghost, Aghast, I guess, A guest” was something that my friend Adam Gilders, who died in 2007, wrote in my parents’ guestbook back in 1995.

The book had a few different titles, but I realized the original guestbook that held Adam’s little message was an existing object already. I love the word guest. It felt right. There was a debate over whether I should put “ghost stories” on the cover. My agent said, “Well they’re not all ghost stories. You’ve done something with this short story form, too. These are stories about detachment, loss and memory.” It was my editor’s idea to de-boss it on the cover so that it’s an impression and not a printed word.

How did you navigate your own personal artifacts and images with the ones that you sought out through eBay, Etsy, et cetera?

“Sirena Di Gali” uses my own original photographs, found images and family snapshots, but very few other stories do. They are either, per story, all my own, or found. For “New Jersey Transit,” I searched specifically for swimmers behind chain link fences. There is so much anonymous, snapshot photography available. And again, like these ghosts, guests—who are these people? With “Billy Byron,” I used a few stock images. I did have to go over everything with the Penguin Random house legal department.

Do you think that using both words and pictures to tell a narrative is more readily received because of this newish world we are in of rapid image-sharing (predominately with Instagram)?

I do. I think we are very sophisticated readers of images, but we don’t know how sophisticated we are. It’s something that excites me, that you and I can look at a completely boring image of a latte and read the same, nuanced things. I think there is a lexicon, or alphabet of reading images that we haven’t organized yet. I think since the invention of photography our understanding of the world has deepened, as has our capacity to be fooled by things. What’s really interesting to me is that we put so much trust in it. I find it sinister. I find it tricky. I find myself second guessing. Do I believe what I’m reading in a picture? Or, What’s the whole story? We’re losing some sense of wonder, or faith, when we rely on images. I think there’s a whole new kind of literacy that has been developing since Daguerre.

Do you think that that we also heavily put trust in one another to believe our deceptions with the images we share?

Yes. Our lives have become a performance because we understand what’s photogenic and what’s not. And I think that’s limiting. I think the idea of what is photogenic or what is beautiful inflects our culture by repetition. This was all predicted by Aby Warburg. When we see something, there is a knee-jerk reaction to believe, because it’s a photograph. Ideas of trust are in question, and that’s why I thought the ghost story could be revisited. There will be more ghost stories that involve photography. Henry James wrote one, in 1896, called “The Friends of the Friends.”

Does your process as a writer differ from your process as an artist? Or perhaps they’re synonymous for you?

I’m in the middle of writing a long-form journalism piece and it’s similar. When I paint I work in series. I’ll paint the same thing seventeen times. With writing, well, I love rewriting. It’s a case of re-writing something seventeen times. Also, when I’m writing, it helps me to look at images and describe them to get tone or to give the reader a sense of two channels working at the same time. My writing will always have an element of, “Reader, look at this,” whether illustrated or not. I like to play with layers of text and image, that involve an imagined image, a description of a real image, and then facts. I do paint more than I write. I find writing harder.

You have a background in swimming. How does this activity/practice of propelling oneself through water relate to or differ from your creative practices?

Both make you tired and short of breath. I rely on the idea of laps, repetition. Finding a rhythm. Finding a zone. If I sit down and work for five hours it feels wonderful. It feels like the focus I had in a practice or when I pushed myself to get up, eat a bagel, to get to the pool. I find that place is very satisfying. And how does it relate? I guess because I know how to do it, to focus like that. That feeling is what I look for when painting and writing: the line on the bottom of the pool. And in terms of propulsion, I think a creative process requires that you slow down. Stamina. Discipline. I mean, all these things have to be at work.

Do you see yourself ever making a book without a visual factor?

I don’t know, because it’s how I write. I would like to. It’s a good idea. In the class I teach at Columbia, Words and Pictures, the first exercise I have everyone do is to find an image from a selection on a table and write about it. When the pieces are read aloud, sometimes I don’t show the class the image.

The text has a different life with the removal of the picture. I’ve written pieces of journalism where I don’t provide the images, where someone illustrates or a photo editor decides. Right now I’m writing an afterword for a Thomas Bernhard novel and I won’t put pictures in it.

Is it terrifying to write when you know that someone else is going to decide what images go with the writing?

I want to design and art direct it all. It’s a part of my writing, a part of the delivery for me, using that entire palette. I can’t stand it, but I get it. And I love collaborating.

About the author

Grace Ann Leadbeater is an artist who is pursuing a Master of Fine Arts in writing at Columbia University. She grew up in Central Florida and lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Annie Ernaux, ‘In Venice’

Annie Ernaux, ‘In Venice’