“Snowy Egret, from the collection of the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology,” Photo by Rosamond Purcell. Courtesy of BOND/360

“Snowy Egret, from the collection of the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology,” Photo by Rosamond Purcell. Courtesy of BOND/360The "Duchess of Disintegration and Decay" Gets a Documentary

A new documentary about Rosamond Purcell, photographer of the afterlives of objects, opens at Film Forum tonight.

August 10, 2016

From the skeleton of a hydrocephalic child to the hides of apes hanging silhouetted and framed by light-filled church windows to the abstracted eyes of moths’ wings, framed to appear predatory, Rosamond Purcell photographs life after death. Known for her still images of artifacts that honor the natural degradation of life, her work portrays both an historical narrative of the lives of these lost and found creatures and her own fictional continuation, her version of their history. Opening tonight at Film Forum, the new documentary, An Art That Nature Makes: The Work of Rosamond Purcell, directed by Molly Bernstein, features the oeuvre of this prolific photographer of natural science.

In an interview with both Purcell and Errol Morris, a longtime fan, the renowned documentarian told The Creators Project, “The irony of Rosy's art is that once absolutely dead, things take on a life of their own." Morris dubbed her a “connoisseur of decay,” to which Purcell objected: “Well, let’s say disintegration. Decay is so smelly, don’t you think?”

Morris responded, “How about we compromise and say disintegration and decay? The Duchess of Disintegration and Decay.”

Purcell's love of photography first began with human subjects, but in the mid-1980s she grew bored and sought out a challenge. Facing her childhood fear of natural history museums, she gained access to the collections at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, where she set up several stuffed monkeys in an eerie, monochromatic scene. Side by side, arms outstretched, their eye sockets stuffed with cotton and their mouths gaping black holes, Purcell’s photograph mimicked “a crowd of medieval people who’d been struck by a meteorite,” she elaborates in the film.

“Norfolk Island Kereru Leiden, from Swift as a Shadow,” Photo by Rosamond Purcell. Courtesy of BOND/360

Purcell often collaborates with natural historians and scientists. Her work with Harvard paleontologist Stephen Gould realized her potential to create artistic renditions that transcended the clinical norm for artifact documentation. "He really had the imagination to see what I was up to,” she told The Creators Project, “and then he had the vocabulary to add the science to it." Her ability to imbue the natural world with a life beyond that which humans bestow upon it led her to publications with National Geographic and of her own books. She even photographed a few trims from Errol Morris’ film, Vernon, Florida.

“Every single trim has its own sense of composition, whether it’s a group of people or a single figure,” she said in our interview. “Nothing is awkward. Nothing is off. Everything can be stilled.” Morris added, "Rosy has found the equivalent of a Paleolithic mound in my office." Limiting herself to available light, Purcell’s photography finds candescence in the cast-off and perceived life amongst shadows.

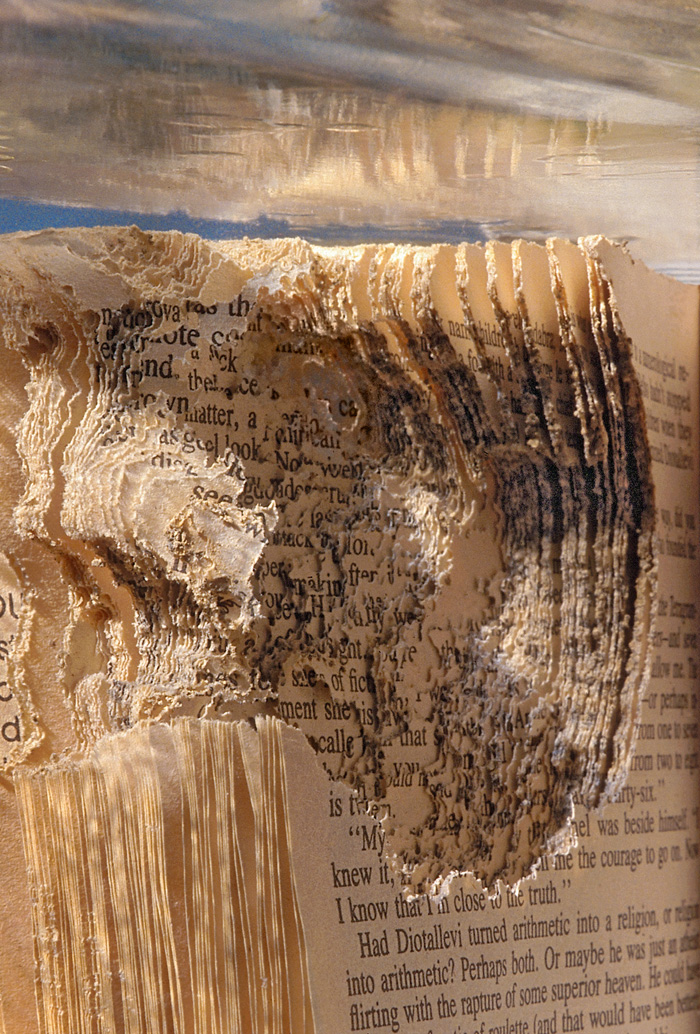

“Umberto Eco Foucault’s Pendulum,” Photo by Rosamond Purcell. Courtesy of BOND/360

The film's opening scenes show the grounds of a 13-acre junkyard owned by an eccentric old man named William Buckminster. A return customer, Purcell bought objects from his massive collection and added them to her own overflowing studio in Boston. Her relationship with Buckminster and his collection was documented in her 2004 book, Owls Head. The camera trails behind Purcell as she follows Buckminster through a maze of detritus. She asks him which items he perceives as “utter junk.” He responds, “Well, it’s rather hard to define since I met you.”

“Rosamond Purcell in her studio,” Photo by: Dennis Purcell. Courtesy of BOND/360

An Art That Nature Makes runs through August 16th at Film Forum. For more information on screenings in other cities, as well as the making of the documentary, click here.

No comments:

Post a Comment