|

| Soul mates … English language translator Flora Drew with Chinese author Ma Jian. Photograph: Antonio Olmos/The Observ |

'It's a silent conversation': authors and translators on their unique relationship

From Man Booker International winner Olga Tokarczuk to partners Ma Jian and Flora Drew … leading authors and translators discuss the highs and lows of cross-cultural collaboration

Claire Armitstead

Saturday 6 April 2019

n the night of last year’s Man Booker International prize ceremony, two winners swept up to the podium – novelist Olga Tokarczuk and her translator Jennifer Croft – but a third was back at their table cheering louder than anyone. “I was thrilled to bits, I still am,” says Antonia Lloyd-Jones. What makes this unusual is that Lloyd-Jones is the Polish author’s other translator, who has been working with her far longer, but wasn’t responsible for the winning novel, Flights. With a shared purse of £50,000 at stake, was there not even the tiniest bit of envy? “We’re a team – of course it’s Olga and Jennifer’s win, not mine, but it’s great for all of us who have spent years trying to popularise her books outside Poland, and it’s great for Polish literature in translation,” says Lloyd-Jones. “This was a major breakthrough after almost 30 years of work. And it has done sales of my own translations a lot of good.” Nifty scheduling by the indie publisher Fitzcarraldo has meant that these include Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, a quirky eco-thriller very different from Flights, which has won Tokarczuk her second Man Booker International prize longlisting. This year’s shortlist will be announced on Tuesday.

It’s not just Polish novels that are enjoying a boost. Sales of fiction in translation were up in the UK by 5.5% last year, with sales of translated literary fiction increasing by 20%. As the UK turns inwards, caught up in an increasingly bitter fight over leaving the EU, readers are looking outwards, with literature from mainland Europe accounting for a large part of the growth. Jacques Testard, who publishes Tokarczuk, is part of a new wave of independent publishers who hope for further integration of translated fiction into the mainstream, pointing out that it is only in the UK that foreign literature is corralled into a separate compartment from that originally written in English. “In France, where a fifth of all books are published in translations, you’ll find Balzac and Bolaño, Calvino and Carrère on the same shelf in bookshops. It’s only in the Anglosphere that it gets set apart.”

That separation is in evidence in the awards world, as well as the bookshop, with the Man Booker International the biggest among a host of grants and prizes for fiction in translation. How did Croft and Lloyd-Jones decide who would take responsibility for the Tokarczuk novel that eventually went on to win? “It’s a matter of trust,” says Tokarczuk. “I’m definitely not the right translator for Flights,” says Lloyd-Jones, “but when it came to Drive Your Plow, Olga said I should do it. She joked that, at 57, she and I are more like [the eccentric narrator] Duszejko, and, well, there’s some truth in that.”

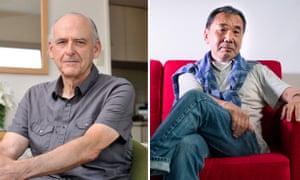

Team Tokarczuk might be close but they are not as intimately connected as the Chinese novelist Ma Jian and his translator Flora Drew, who is also the mother of their four children. “Flora is the only person who has translated my books into English. She came to interview me in Hong Kong on the eve of the handover. Her Chinese was very good, so I gave her copies of my books, and said, half-jokingly, that she could translate them into English if she liked. It was a strange thing to say, but there was feeling of destiny,” says the novelist. Their most recent collaboration was on China Dream, a ferocious satire charting the mental breakdown of a corrupt local government official. It was published in English last autumn but is unlikely ever to be read in the original Chinese – which Ma nevertheless regards as the master copy – because censorship in China is now so extreme that even Hong Kong publishers no longer dare defy the ban that has long prevented his novels from being published on the mainland.

Ma speaks little English, so he talks through Drew in life as well as work. Is it a challenge to separate the professional from the domestic? “The Ma Jian I translate is a very different entity from the Ma Jian I live with,” says Drew. “There is never any confusion. I never feel I’m translating the words of the person I’ve just had supper with, or who’s just taken our children to the park. Knowing him so well though means I can in some strange way become him, and write the translation not as a friend or a translator, but as Ma would if he were writing the book in English. There are times during the translation when I feel we are having a silent conversation with each other that we don’t have time for in real life. Many of his books have references to places we have been together, dreams of mine that I have told him about or things our children have said.”Relationships between writers and translators are not usually so close, and not only because they can often live thousands of miles apart. Sam Taylor, a French specialist now living in the US, is also on the Man Booker International longlist with Four Soldiers, a novella by Hubert Mingarelli set near the Romanian border in the last days of the Russian civil war. He proposed the book himself to its publisher Granta. His output in the last couple of years also includes two controversial novels, Lullaby and Adèle by the Paris-based Moroccan-French writer Leïla Slimani. In neither case did he meet the authors before taking on the novels. “I don’t remember having any direct interaction with Leïla on Lullaby, although she wrote me a very nice thank you email afterwards,” he says. “With Adèle, I had a list of about 15 questions that I sent to her after translating the book (and before revising it). She answered those questions and we exchanged a few emails.”

The pairing with Slimani is particularly striking in that Taylor is male, while Slimani’s work is strongly sexualised and centred on the female body. Did either of them ever question whether it might be a job for a woman? “Of course not!” says Slimani. “Littérature is meant to be universal. I write about women but I hope men can identify with my characters. And Sam understood in a very subtle way my characters and also my style, what atmosphere I wanted to instil, what music I wanted to create with my words. It is magic when you feel that someone understands and respects your work so much. When I read my book in English I always think: that’s the exact word I would have chosen.”

Taylor was aware of gender as a potential issue, although, he says, “neither Leïla nor the book’s female editors ever mentioned it. In the original French, all genitalia, male or female, is called simply “sexe”, which is a very neutral word. There are no neutral words for genitalia in English – everything tends to sound either scientific or pornographic or comical – so I used the word that, in each case, seemed to best fit the context. But I didn’t want to be a man imposing my viewpoint or sensibility on a female protagonist and female author, so I highlighted most of those word choices in the text and asked Leïla and my editors if they thought this was the right word. I don’t think any of those choices were changed or even questioned, but it seemed important to put them up for discussion.”

‘When I read my book in English I always think: that’s the exact word I would have chosen’ … Leïla Slimani, left, and Sam Taylor

A novelist as well as a translator, who fell into translation after giving up a career in journalism to write books in France, Taylor doesn’t take everything he is offered. “I turned down the chance to translate Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission because the Charlie Hebdo attack occurred a couple of days after I received the offer. I have no regrets about that,” he says (the job went to Lorin Stein, former editor of the Paris Review, who has since gone on to translate two novels by France’s new enfant terrible Édouard Louis).

A novelist as well as a translator, who fell into translation after giving up a career in journalism to write books in France, Taylor doesn’t take everything he is offered. “I turned down the chance to translate Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission because the Charlie Hebdo attack occurred a couple of days after I received the offer. I have no regrets about that,” he says (the job went to Lorin Stein, former editor of the Paris Review, who has since gone on to translate two novels by France’s new enfant terrible Édouard Louis).

The literatures of French and English might be different, but as Taylor points out: “Most European languages (and certainly French) are underpinned by a roughly equivalent set of philosophical values and a shared history.” What of those languages that are the product of cultures with little common ground? The traditional answer has been that they rarely get translated, though research commissioned by the Man Booker International prize revealed the situation to be slowly improving, with a growing demand for Chinese, Arabic, Icelandic and Polish languages.

“Chinese and English are as far apart as any two languages could be,” says Drew. “I can read a book in French easily, but after all these years, Chinese is still a struggle – there are many characters I don’t know, or have forgotten, classical allusions that I miss. Chinese has no tenses and is more concise than English, so meaning is often inferred through context. But although Chinese sometimes feels like a different universe, I’m always surprised by how much can be translated – how images and metaphors can work across cultures.”

Among the initiatives that encourage a wider range of writing in translation is the new EBRD prize, which awards €20,000 to a book from the interestingly arbitrary landmass served by its sponsor, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (which extends from the Baltics to central Asia and the Mediterranean countries of Africa). Last year’s inaugural prize went to the Kurdish/Turkish writer Burhan Sönmez translated by Ümit Hussein. This year’s was won by the first Uzbek novel ever to be translated into English, The Devils’ Dance.

Its author is Hamid Ismailov, a genial 64-year-old journalist who came to London shortly after being forced to flee Uzbekistan in 1992 and has had a day job at the BBC ever since. He was matched with his translator, Donald Rayfield – an emeritus professor of Russian and Georgian – by a new translator-run publishing house, Tilted Axis, set up in 2015 to champion neglected languages. When I meet up with them in the BBC’s London headquarters, their rapport is striking. “I was the last person to choose for this,” jokes Rayfield, “but as the Russians say: ‘If there’s no fish, a crab will do.’”

Rayfield not only had to learn Uzbek to translate the novel, but had to bone up on Tartar, Farsi, Tajik and Kyrgyz as well. How many languages does Ismailov speak? “When you speak Uzbek,” the novelist quietly explains, “you understand many Turcik langages and with Russian you can understand many Slavonic ones.” He is a translator himself, working in both directions between Russian, Uzbek and various European languages. Several of his own novels have been translated from Russian into English, but the impossibility of getting an Uzbek novel by a banned writer into the hands of any readers at all inhibited his reputation in his mother tongue until the internet solved the problem for him. He published The Devils’ Dance in chapters on Facebook and it went viral through the “Stans” – the five formerly Soviet countries in central Asia for whom his central character, the real-life early 20th-century writer Abdulla Qodiriy who was executed in 1938, was a hero. The pair are less forthcoming about a third name that appears on the novel’s title page – John Farndon – credited with translating the poetry in the novel. “There was no conversation. I was somewhat taken aback by changes to my original translations,” recalls Rayfield.The difficult birth of The Devils’ Dance in English underlines the extent to which translation is not only a two-way but a three-way relationship, with the publisher – the person who takes the financial risk – as the third partner. Tilted Axis was set up by Deborah Smith partly with the prize money from her 2016 Man Booker International win for her translation of Korean author Han Kang’s The Vegetarian. Smith made substantial cuts to The Devils’ Dance(though it still checks in at more than 400 pages). Her decision to bring in a poetry translator was in line with a time-honoured tradition in which a named poet works from a literal translation rather than the original.

Smith is better placed than most to understand the demands of cultural transposition: as translator of three novels by Han, she had to negotiate Korean systems of religious belief, family relationships and linguistic practice. She too learned the language specifically to translate the novels and found herself at the centre of a storm when her translation of The Vegetarianwas challenged on the grounds of accuracy.

“A scene where I had the main character close a door with her foot instead of her arm is one Korean academics like to bring up,” she says. “There were 67 [errors], by the way. I like to state that publicly in case anyone mistakenly assumes it’s something I’d want to hide.” The errors were corrected in later editions and Han Kang’s faith in Smith is unshaken. Smith is currently living in South Korea and working on a novel by another female Korean novelist, Bae Suah, which is due to be published by Jonathan Cape next year. She’s not about to diversify into other languages just yet. “I’m trying to find different ways to spread the translation gospel: publishing, teaching, mentoring. Writing about all aspects of translation: the flow between languages, the discourse around it, all the people who make it happen.”

Faithfulness, as opposed to accuracy, is always a difficult issue, as novelist Tim Parks concedes. “I think there’s usually a mistake of nuance on every page of every book. Sometimes scandalously so,” he says. As an author and a translator he has experience in both directions, and he stresses that translators are often the best readers. “I have a Dutch translator who keeps writing to me and telling me about the mistakes I’ve made in my own books. It can be spelling or continuity, and she’s always right. Just occasionally it’s really embarrassing, but people like that give you the chance to fix the next edition.”

Parks has written that: “The translator should do his job and then disappear. The great, charismatic, creative writer wants to be all over the globe. And the last thing he wants to accept is that the majority of his readers are not really reading him. His readers feel the same. They want intimate contact with true greatness. They don’t want to know that this prose was written on survival wages in a maisonette in Bremen, or a high-rise flat in the suburbs of Osaka. Which kid wants to hear that her JK Rowling is actually a chain-smoking pensioner?”But translators fall into different camps, described by New Yorker critic James Wood as “originalists” and “activists”: “The former honor the original text’s quiddities, and strive to reproduce them as accurately as possible in the translated language; the latter are less concerned with literal accuracy than with the transposed musical appeal of the new work,” he wrote. Any decent translator must be a bit of both.” Or, as the cultural critic Marina Warner has put it: “Should a translator respond like an aeolian harp, vibrating in harmony with the original text to transmit the original music, or should the translation read as if it were written in the new language?”

“It’s obviously a simplification, but I imagine I would be closer to the activist side of the spectrum,” says Taylor, whose less aeolian approach set him at odds with one French writer, Maylis de Kerangal. Her novel’s French title was Réparer les Vivants, and Taylor called his translation The Heart, while the Canadian poet and translator Jessica Moore chose the more literal Mend the Living for this story of the day in the life of a donated heart as it is rushed from one person to another. The translations were commissioned simultaneously by editors in the UK and the US, and both won awards (Mend the Living scooped the Wellcome prize while The Heart won the French-American Foundation prize) but De Kerangal has ruled that Moore’s is more faithful to her writing and she should therefore do all her future novels: “It is so fascinating to see what choices were made at every turn. The opening sentence, for example, feels completely different to me in our versions,” says Moore. Even the dead boy’s surname is different, though interestingly it’s Taylor who kept De Kerangal’s Limbres, while Moore went for Limbeau.

According to another busy translator, Frank Wynne, problems often arise when a writer thinks they have a better command of English than they actually do. One of his worst experiences was with French film director Claude Lanzmann who was “hugely intrusively involved” in the translation of his 2012 memoir The Patagonian Hare. “He binned the original Italian translation and redid mine line by line. He insisted on using the phrase ‘leonine contract’ to mean a contract in which one person took the lion’s share. I didn’t in the end meet him and it might have been useful if I had, so that he’d gone into it with more of a sense of trust.”

A translator from both French and Spanish – who had novels in both languages on the longlist of last year’s Man Booker International and is currently based in Mexico – Wynne’s relationships with writers tend to be brisk. “Some don’t reply at all. The trouble is the more successful a writer is, the more languages there are.” One of his top-selling authors, the French crime novelist Pierre Lemaitre, deals with the problem by collating questions from all his 35-40 translators into a round-robin crib sheet.

Jay Rubin, one of the four translators who have made the Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami into an English language superstar, says he learned early on to correspond sparingly. “The worst thing I did was with The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. I got together with him in Tokyo and drove him absolutely crazy for a whole day giving him little questions one after another. This is not a very kind thing to do to an author.”

Rubin co-translated the book Bird Chronicle with Philip Gabriel, because it ran to three volumes, and its length defeated him. Did they collaborate? “The biggest disagreement we had was whether to use the word bathroom or lavatory.” (Murakami ruled in favour of bathroom.) But, he says, “All of us stick pretty closely to the tone and style of Murakami’s writing, and thanks in large part to the simplicity of his style, the voice is pretty consistent. There aren’t that many ways to say ‘Sunday was another fine clear day’.”

If that sounds like damning with faint praise, the compliment was returned by Murakami, when he wrote the introduction to a well-received recent anthology of Japanese short stories edited by Rubin, which Rubin himself then translated. “Some [stories], of course, could be characterized as ‘representative’ works, but, frankly, they are far outnumbered by stories which are not,” wrote the novelist. How did that make Rubin feel? “I giggled when I read that ‘frankly’,” he says. “But you’re getting the unvarnished Murakami view of the book.”

For Ann Goldstein, translating a more recent superstar, Elena Ferrante, there was no such back and forth. She had no direct contact with the author, whose true identity is a closely guarded secret. She was chosen on submission of a sample translation of a previous Ferrante novel, and corresponds with her on email via her publisher. Though the novels themselves weren’t written in Neapolitan dialect, the dialogue in the HBO TV adaptation – partially scripted by Ferrante – is. “My role has been translating them so that HBO can read them,” says Goldstein.

Just how difficult Neapolitan can be, even to someone steeped in Italian, became clear to the author Jhumpa Lahiri when she took on two novels by another of the southern Italian city’s writers, Domenico Starnone. Lahiri moved from the US to Rome and dedicated herself to writing in the language of her host country, the progress of which she documented in a fascinating bilingual book, In Other Words. Immersion in standard Italian didn’t prepare her for some of Starnone’s language though. “Some of his dialect I intuited. Other terms, rife with violence and obscenity, were politely translated into Italian for me by Starnone himself,” she has said. Lahiri’s working relationship with Starnone is a passionate cross-cultural conversation, which for their latest collaboration, Trick, took in Kafka and Henry James. At a public launch in London last year, an overawed fan asked if it was necessary to know so much. Not at all, replied Lahiri. For most readers, it’s just a story of a grandfather left in charge of his four-year-old grandson.

Starnone is now going to translate Lahiri’s English introduction for the Italian edition of her new Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories. But she is saving the biggest challenge for herself: the English translation of her own first novel written in Italian. Dove mi trovo has already been published in several other languages. “The idea of my own creation in Italian not having a life in English yet is interesting,” she says. “The problem is: how do I turn myself back on myself? Mentally I have to go into a place where I’m two people.” Is self-translation the most intimate relationship between a writer and a translator? Perhaps not. “In Chinese,” says Ma Jian, “a soul mate is described as zhiyin – someone who ‘understands your music’ and that is what Flora is to me.”

No comments:

Post a Comment