|

| Self Portrait in Crouching Position, 1913 by Egon Schiele |

Life in Motion: Egon Schiele and Francesca Woodman review – vulnerable beauty

Egon Schiele and Francesca Woodman both died in their 20s. Here, their elegant images of the body under duress expose the difference between an artist’s real and invented dramas

Laura Cumming

Sunday 27 May 2018

Two images spark a flame, unexpectedly, at the start of this show. One is a self-portrait by the American photographer Francesca Woodman, in which she crouches in a shadowy room with what appears to be a gaping wound in her side. Look again, and you see that the zip of her dress is undone, exposing a gash of white skin in the darkness. The other is a drawing by Egon Schiele of an emaciated young man seen from behind, a tattered jerkin hauled over his bony arms that covers very little of his abject nakedness. Both artists use a single garment brilliantly to invoke mankind’s vulnerability, the exact condition of Lear’s poor, bare, forked animal.

Boy meets girl, that is the story of this show. And in some respects, the two are a perfect match: Egon Schiele (1890-1918), the most radical artist of the Austro-Hungarian empire, both exposed and exposing in his drawings and paintings – his self-portraits naked, agonised, with arms outflung, like crucifixions without the cross; and Francesca Woodman (1958-1981), also powerfully gifted, appearing as the subject of her own intense and enigmatic monochrome photographs.

Teenage prodigies, dead in their 20s – Woodman at 22 by her own hand, Schiele carried off by Spanish flu at 28 – they were almost equally prolific and driven. And what they seem to share, moreover, is an obsessive interest in the body under pressure, suffering, strained, taken to physical extremes: the outward expression of the inner being.

Straight away this puts the emphasis fully on content. In the art of each there is the single figure, splayed, crouched, restless, hunched, bent, dangling, curled – in foetal anguish (Schiele), next to a bowl of writhing eels(Woodman) – and almost always alone, in the chilly white space of his page or the gloom of her derelict building. People collapse, lie flaccid as abandoned dolls, or sit on the floor, knees tensely pent to their chins.

Backs are turned, faces concealed, genitals exposed. Schiele’s waifs in general have nowhere to hide, except behind the odd scrap of fabric; Woodman is always hiding, clambering into the fireplace, disappearing round doors or folding herself inside flaps of old wallpaper. There is the relationship between bodies and space, and between people and their clothes. A dress, in both, may be a fragile old vestment that barely conceals the naked body beneath. But a stocking loosened pornographically in Schiele becomes a sign of forlornness in Woodman.

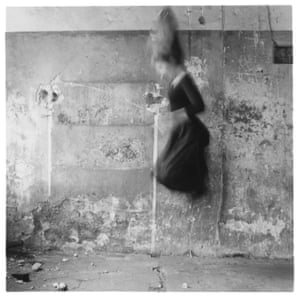

And so the similarities begin to dissolve. The show’s title refers to motion – registered quick as a flash in Schiele’s precise and proleptic pencil; recorded more slowly by Woodman. One of her methods was to set a long exposure time and then move ever so slightly, to get the familiar blur of 19th-century photographs. In one picture she jumps into the air, hair streaming like ectoplasm. In another, crouched down and apparently about to reach for help or fall forward, she vanishes in an anonymous frisson. Woodman is the model for all of these images, but they are by no means conventional self-portraits.

And nor are those of Egon Schiele, of course, who is seen here glowering, crouching, grimacing and in raw-red masturbation. He is a martyr, a loner, a madman tearing at his hair. Ever the victim, he finds the victim in others. It is rightly said that his nubile girls and boys may be naked but they are never erotic, partly because every position they find themselves in involves such conspicuous discomfort. And to his fiercely beautiful line, so incisive and agile, describing the angular contours of each figure, comes the overlay of watercolour that makes his sitters appear mottled, bruised, exhausted, ill with those arsenical green patches.

And yet, of course, they are all so elegant. This is Schiele’s unique invention, this combination of stylishness and suffering. And perhaps Woodman has a little of it too, for there is a touch of the fashion plate about her appearance in vintage clothes, with calla lily, with furs or velvet shoes. She even sent her work to fashion magazines, which rejected her at the time but have been in her debt, somewhat, ever since.

If Schiele had drawn Woodman she might have fitted right into his art; the question is what she took from him. Certain juxtapositions in this show – of poses and expressions – suggest that she had looked hard at his work. Unfortunately the catalogue, unusually weak for a Tate publication, has nothing to say about this.

Walls and galleries alternate between the two artists, and alas the to and fro begins to pall. Woodman’s highly original metaphor of the house-haunting woman starts to look repetitive after 50 variations, which is quite unfair, given that most of this work was made at the age of 21.

What inevitably fascinates far more is the spectacle of Schiele’s graphic genius. His lexicon of marks, for instance: an L, superbly placed to indicate a shoulder blade; an I, magically indicating the back crook of a knee; the way his whiplash line deepens, with charcoal, into something resembling litho; his use of ladders to draw reclining figures from above, upending the page so that they appear even more estranged; his use of brown paper and white watercolour to bring a face hurtling out of the past. There are almost 50 works here, borrowed from around the world, some of them rarely seen in Britain, and each with this phenomenally powerful register.

The whole show is theatre. Woodman hanging herself, as it seems, by knot of her own hair, or disguised in the bark of a tree; Schiele gaunt and staring, bony fingers knotted over his crotch, or drawing the thin, uneasy faces of children persuaded into his studio from the street. But what Woodman performs, in person, is a kind of invented melodrama of evolving scenarios. Schiele sees and draws, instead, the involuntary drama within. He does not make it up.

No comments:

Post a Comment