HOW TO WRITE LIKE JOAN DIDION

MAY 22, 2015

The Key to writing like Joan Didion is to combine detailed, thorough description with a hint of biting irony. This primer is for both fiction writers and journalists who are struggling to make their work more interesting. Luckily, Didion can elevate the mundane and deflate illusions of grandeur, all in one essay. For this article, I will be using examples from her collected nonfiction, We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live.

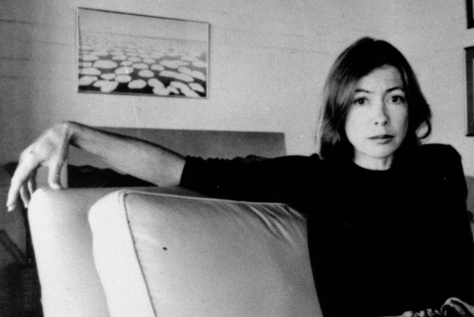

Joan Didion was born in Sacramento, California in 1934, and has written many works of fiction and nonfiction the chronicle life in the state. She looked at the insanity of Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s, the rise of militant subcultures like the Black Panther Party and the Manson “family, as well as the intersection of bureaucracy, rebellion and politics. In her later years, her work has become far more personal, with books like The Year of Magical Thinking detailing the sudden death of her daughter and her husband. Didion was also associated with the “New Journalism” movement popularized by Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe, but her style differs significantly from their work.

1. For every long sentence, you have to drop an anchor and slow down the pace.

Joan Didion often combines long, drawn-out sentences with short ones. Consider the beginning of one of Didion’s most famous essays, “Slouching Toward Bethlehem.”

“The center was not holding. It was a country of bankruptcy notices and public-auction announcements and commonplace reports of casual killings and misplaced children and abandoned homes and vandals who misplaced even the four-letter words they scrawled. It was a country in which families routinely disappeared, trailing bad checks and repossession papers. Adolescents drifted from city to torn city, sloughing off both the past and the future as snakes shed their skins, children who were never taught and would never now learn the games that had held the society together. People were missing. Children were missing. Parents were missing. Those left behind filed desultory missing-persons reports, then moved on themselves.”

Notice how the content of the sentences reflects their length–the opening sentence, in its brevity, suggests portent, and the second one reflects the unleashing of chaos itself.

2. In the same vein, build up a certain tone, then knock it down.

Part of the pleasure of reading Didion is that she goes in one direction, then immediately slows down. detailed <—> emotional. I’ll leave you with a fragment from one of her other classic essays, “The White Album”:

“We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.

Or at least we do for a while.”

The White Album, which Martin Amis celebrated Didion for as a poet of the “Great California Emptiness”, deals primarily with the deceit and illusions of living on the West Coast. This fragment from the opening paragraph effectively reflects the main theme of the book, that not everything is as it seems. Use the rhythm of your prose to reflect that.

3. Everyone sees themselves as heroes in their own story.

Play with this idea when describing others. In her essay, “Notes Toward a Dreampolitik, Didion describes a pentecostal pastor called Brother Theobold. While her tone is primarily one of half-interested skepticism, one passage brings out the élan and method of her subject:

“He seemed to be one of the people, so many of whom gravitate to Pentecostal sects, who move around the west and the South and the Border states forever felling trees in some interior wilderness, secret frontiersmen who walk around right in the ganglia of the fantastic electronic pulsing that is life in the United States and continue to receive information only through thee most tenuous chains of rumor, hearsay, haphazard trickledown.”

Yes, her description paints him in an odd light, and perhaps even portrays his as a huckster, of sorts. But what this passage does is internalize the tone of heroism she sees inherent to the pastor’s character. The people you meet or the characters you make need not be heroic, but if they believe they are, it is often enough.

4.The first and last sentences of a paragraph are paramount.

One thing that Didion does so effectively is that she builds paragraphs in an assortment of different shapes. Take a look at the one below, from “Goodbye To All That”:

Nothing was irrevocable; everything was within reach.Just around every corner lay something curious and interesting, something I had never before seen or done or known about. I could go to a party and meet someone who called himself Mr. Emotional Appeal and ran The Emotional Appeal Institute or Tina Onassis Blandford or a Florida cracker who was then a regular on what the called “the Big C,” the Southampton-El Morocco circuit (“I’m well connected on the Big C, honey,” he would tell me over collard greens on his vast borrowed terrace), or the widow of the celery king of the Harlem market or a piano salesman from Bonne Terre, Missouri, or someone who had already made and list two fortunes in Midland, Texas. I could make promises to myself and to other people and there would be all the time in the world to keep them. I could stay up all night and make mistakes, and none of them would count.

Notice how the first and last sentence hold the whole paragraph together. Didion opens with the general, explores the specific, including names, examples, places, all in a way to cleverly account for the diversity of things happening in New York City. But to close to the paragraph, she returns with a general statement, almost in a way that reinforces what she said at the beginning. So don’t just plot your stories. Plot your paragraphs.

5. “We tell ourselves stories in order to live” – Didion is always playing with the concept of reality in her stories.

After all, they are stories. If you’re writing about youth, hyperbole will reflect your lofty hopes. if you’re writing about an intellectual, quote what they say and isolate it to put their words under the microscope. Even if they’re stuffy bureaucrats, describe the mundane in great detail. Take a look at the example below to see just how many stories Didion includes in one paragraph:

“I recall being told, when I first moved to Los Angeles and was living on an isolated beach, that the Indians would throw themselves into the sea when the bad wind blew. I could see why. The Pacific turned ominously glossy during a Santa Ana period, and one woke in the night troubled not only by the peacocks screaming in the olive trees but by the eerie absence of surf. The heat was surreal. The sky had a yellow cast, the kind of light sometimes called “earthquake weather”. My only neighbor would not come out of her house for days, and there were no lights at night, and her husband roamed the place with a machete. One day he would tell me that he had heard a trespasser, the next a rattlesnake.”

This paragraph effectively demonstrates how micro-stories, or stories-within-a-story, can bring a setting to life, establish an atmosphere. In this case, the portentous aspect of life in Los Angeles is not just a vague feeling, but the binding theme of several anecdotes, many of them word-of-mouth.

6. Writers overthink.

If you’re writing with a personal tone, try to bring out your hopes and fears, no matter how many you have. (134). In “The White Album”, the opening essay in Didion’s book of the same name, Didion not only looks at her time and place, but how her mode of thinking has shaped her writing style.

“This was an adequate enough performance, as improvisations go. The only problem was that my entire education, everything I had ever been told or had told myself, insisted that the production was never meant to be improvised: I was supposed to have a script, and I had mislaid it. I was supposed to hear cues, and no longer did. I was meant to know the plot, but all I knew was what I saw: flash pictures in variable sequence, images with no “meaning” beyond their temporary arrangement, not a movie but a cutting room experience.”

To write like Didion, you don’t necessarily have to be overtly self-analytical. But you must atone for your doubts, what works in your writing and what roadblocks prevent you from aptly describing a scene in full.

7. Details reveal a lot about a scene — but often, they reveal the opposite of what is expected.

One of my favorite examples of this is in part three of “The White Album”, were Didion attends a Doors recording session in Los Angeles. When I first read this, I was very intrigued because of the mythos surrounding the Doors frontman Jim Morrison. In fact, Didion first establishes the myth:

“There was everything and everybody The Doors needed to cut the rest of this third album except one thing, the fourth Door, the leader singer, Jim Morrison, a 24-year-old graduate of UCLA who wore black vinyl pants and no underwear and tended to suggest some range of the possible just beyond a suicide pact.”

But then, when he does enter, she reverses our expectations. Not only did nobody acknowledge his entrance, but when he did speak, it was to argue with Manzarek, the keyboardist, about rehearsal. Then, when they were on break, Morrison’s mystique took an odd turn:

“Morrison sat down again on the leather couch and leaned back. he lit a match. He studied the flame awhile and then very slowly, very deliberately, lowered it to the fly of his black vinyl pants. Manzarek watched him. The girl who was rubbing Manzarek’s shoulders did not look at anyone.”

The scene quickly turns from the mythical to the bizarre, and Morrison, still praised as a rock god today, is in this scene no more than a strange fool. it doesn’t mean that Didion was trying to bash him. But to write like her, be aware of the expectations, of what people expect to read. That way, you can infuse your prose with humor and irony.

No comments:

Post a Comment