Woody Allen

LIFE

Out of Print: Andrea Dunbar

Andrea Dunbar’s 1977 *The Arbor* begins with this sparse but telling stage direction: “The GIRL was with her boyfriend. They were at his friend’s. She had known the BOY for ages but had only been going out with him for three months.”

|

| Julia Donaldson |

She published her first book in her 40s and became the biggest selling author of the past decade in any genre – The Gruffalo alone has sold 13m copies. How did this former busker make it so big?

The room where the children’s author Julia Donaldson writes – the heart of her vast picture book empire – is down a winding staircase, in the cellar of her grand white house in Steyning, West Sussex. Her desk looks out on the street at knee height. “I’m thinking of writing a book about legs,” Donaldson said, as she showed me around the house this summer. Children from the nearby school often wave in at her as they pass. Donaldson is well known in Steyning, due to her frequent signings at the local bookshop. She and her husband, Malcolm, a retired paediatrician, recently bought the local post office to save it from closure. But elsewhere she can walk the pavement without being recognised. “I got a letter the other day for Jacqueline Wilson,” Donaldson told me. “It said: ‘You’re my favourite author!’”

|

| Troubles is the first in JG Farrell’s (above) trilogy on the British empire, which also includes The Siege of Krishnapur and The Singapore Grip. Photograph: Jane Bown |

Michael Connelly's crime novels are so infused with Los Angeles atmosphere that some readers might have trouble imagining his key protagonist, Detective Harry Bosch, surviving for long in any other environment. In more than a dozen previous novels, Bosch has occasionally followed a case beyond L.A. -- to Mexico, say, or Las Vegas. But the City of Angels is where he begins and ends his work, searching every overlook and underpass in his single-minded mission to bring murderers to justice.

|

| Lauren Groff |

Put down those beach reads, and get ready for a fresh crop of highly anticipated literature from some America’s favorite authors, from Lauren Groff to Susan Orlean. It’s the perfect season to cozy up with one of these books.

|

| Jonathan Franzen |

A raft of sea otters are at play in a narrow estuary at Moss Landing, near Santa Cruz, Calif. There are 41 of them, says a guy in a baseball cap. He counted. They dive and surface and float around on their backs with their little paws poking up out of the water, munching sea urchins or thinking about munching sea urchins.

April 15, 2021

While the most recent leg of our International Booker Prize longlist journey involved a quiet drive into the countryside, today sees us embarking on a much more ambitious expedition, possibly the most expansive in the prize’s history. While it’s cold outside, there is an atmosphere of sorts, and we’re certainly not alone, with about six thousand other intrepid adventurers for company. But if nobody can hear you scream in space, that’s probably because nobody’s listening, so luckily today’s choice rectifies that oversight. Do you have something you need to get off your chest? Come this way…

*****

The Employees by Olga Ravn

– Lolli Editions, translated by Martin Aitken

(digital review copy courtesy of the publisher)

What’s it all about?

In the twenty-second century, far from Earth, a vessel known as the Six-Thousand Ship is on a Star Trek like voyage of enquiry, seeking out new worlds and lifeforms. The ship eventually finds a planet dubbed New Discovery, and on exploring its surface, the crew find strange objects, unmoving yet undoubtedly showing signs of life. The objects are taken back to the ship and placed in rooms, ready for analysis.

There's a moment in "Exit Music," Ian Rankin's 17th -- and, he says, last -- novel about Detective Inspector John Rebus, when a man with a tape recorder explains, "I'm putting together a sort of soundscape of Edinburgh. From poetry readings to pub chatter, street noise, the Water of Leith at sunrise, football crowds, traffic on Princes Street, the beach at Portobello, dogs being walked in Hermitage . . . hundreds of hours of the stuff." That could be Rankin himself speaking, because in the Rebus novels he's provided a portrait of his chosen city that's as rich, detailed and loving as any that any crime writer working today has given us of any city in the world. "Exit Music" is far from the best of the Rebus novels, but if it is truly the last of them, attention must be paid: This has been one of the best police procedural series ever written.

|

| Dante |

In 2006, the poet Mary Jo Bang came across Caroline Bergvall’s “VIA (48 Dante Variations),” a pastiche poem containing every translation of the first stanza of Dante’s Inferno Bergvall could find in the British Library. The famous opening lines — which are about Dante being lost, midway through life, in a dark wood — are simple and decorous in the original Tuscan dialect. Yet no two translations sound exactly the same. Bang liked the piece so much that she thought she would try her own hand at the stanza, and see what she made out of Dante’s Italian. The exercise led her to spend the next seven years translating all of Inferno, before continuing to work on the rest of his Divine Comedy. Now, her take on Dante’s Purgatorio, the lesser-known yet much-loved second canticle of his epic poem, has hit the shelves — just in time for the 700th anniversary of the great poet’s death.

|

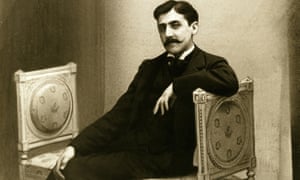

| Mysterious no more... Marcel Proust, photographed in the late 1890s. |

|

| James Wright |

JAMES WRIGHT

A Life in Poetry

By Jonathan Blunk

Illustrated. 496 pp. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. $40.

James Wright loved to recite poems he knew by heart, and he seemed to know most of them. Friends described his aural memory as “phonographic.” “It’s as if he has a piano roll in his head,” his college roommate said. Donald Hall recalled Wright declaiming German poetry “for 20 minutes to an astonished assembly of mathematicians.” At a crowded party, while reciting Edwin Arlington Robinson, Wright brushed against a lit stove and set his coat on fire. Oblivious, he continued his performance while a friend poured beer down his smoldering backside.

The novelist Edmund White has called biography “the most middle class of all forms, the judgment of little people avenging themselves on the great.”

The Argentine writer Alberto Manguel’s new novel, “All Men Are Liars,” is like an Off Broadway elaboration of Mr. White’s cutting observation. It’s a series of uncomfortable interviews with a would-be biographer in which little people approach a great writer’s corpse and leap on and off it like engorged fleas.

A

|

| Paula Rego in front of Dogs of Barcelona, 1965 |

Michael McNay

Wenesday 8 June 2022

|

| Paula Rego |

The Victoria Miro gallery announced Rego’s death on Wednesday, saying: “She died peacefully this morning, after a short illness, at home in north London, surrounded by her family. Our heartfelt thoughts are with them.”

|

| Most of Paula Rego’s late and best work was done in pastel, such as this piece, Love, 1995. |

However volatile her subject matter, her art never tells you what to feel, writes the Guardian’s art critic – although she could indulge in a kind of knockabout buffoonery

When Paula Rego showed at the Serralves Museum in Porto in 2004, such was her fame in her native Portugal that the museum was kept open all night, and she was frequently accosted on the streets of the city with something like adulation. Fame never really affected her, and while some artists coast through their later careers, Rego continued to surprise and shock right to the end. Her work was both deeply personal and spoke of larger issues.

TESS IN THE CITY

June 21, 2020

“Obsessions are the only things that matter.”

― Patricia Highsmith

Dubbed “the Poet of Apprehension” by Novelist Graham Greene, Patricia Highsmith is probably best known for Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley (for which she won the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière). She was born as Mary Patricia Plangman but took her stepfather’s last name when her mother remarried. She was born in Fort Worth, Texas but grew up in New York (Manhattan and Astoria, Queens). In 1952, Highsmith published “the first lesbian novel with a happy ending” — The Price of Salt under the pseudonym Claire Morgan. In 1990, Highsmith republished the book as Carol under her own name. The New Yorker notes that The Price of Salt, or Carol, is the only Highsmith novel where “no violent crime occurs.” Highsmith spent much of her life as a recluse despite her many lovers. She died at 74 in Switzerland and left three million dollars of her estate to the Yaddo artist community in upstate New York.

From Stephen King to Oscar Wilde and Tana French, novelist Gabriel Bergmoser chooses Halloween reading that does more than simply shock and scare

Gabriel Bergmoser1. Red Dragon by Thomas Harris

The Silence of the Lambs gets all the attention, but the best Hannibal Lecter novel is still the first; a book that suggests the most horrifying of evils can grow from an all too human place, and that even heroes can carry something monstrous inside them. Every Lecter story on some level features an implicit Faustian bargain and none is more tragic than FBI crimimal profiler Will Graham’s knowing choice to sacrifice his own fragile peace of mind to stop a killer he understands all too well.

2. The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

There are no real villains in Oscar Wilde’s first and only novel. The lurking danger of this book is our capacity for vanity and how it can literally and metaphorically disfigure us, how obsession with retaining beauty will inevitably lead to its destruction. Even Wilde’s central monster, Dorian himself, is more tragic idiot than conniving mastermind, a youthful dope consumed by a pathological belief that the only thing worth having is beauty at any cost. His descent would almost be funny if it wasn’t so chillingly believable.

3. Horns by Joe Hill

Sometimes horror, even at its darkest, is the window dressing for something more tender. That’s the case with the unique and entirely enrapturing Horns, a book that starts out as a twisted revenge story before slowly becoming something more sprawling, knotty, and ultimately hopeful. Horns is by turns a gothic romance, a murder mystery, a supernatural thriller and a biting satire on how quick we can be to judge despite the darkness we all harbour.

4. The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty

Often the best horror stories are the ones that believe, through all the death, jump-scares and creepiness, in the fundamental triumph of goodness. That The Exorcist was long considered one of the most terrifying novels ever is in large part is down to how deeply we are led to care about the desperate plight of its central characters, and how carefully detailed every one of them is. The evil they face is huge and incomprehensible, but not, in the end, insurmountable, and much of the book’s (and film’s) power comes from the ultimate hard-won victory of a small group who sacrifice everything for an innocent child.

5. Ring by Koji Suzuki, translated by Robert B Rohmer and Glynne Walley

Successive film adaptations have not managed to capture the true power of this relatively demure tale of a cursed videotape, a chilling and all too human story of coming to understand your own insignificance in the face of forces beyond your comprehension. While Ring is a classic, it’s in its two sequels that Suzuki revealed the scope of his ambition, organically building on his horror fable to craft something far more epic and transcendent than any filmed version has yet realised.

6. Psycho by Robert Bloch

To be clear, like Jaws, the film is better; Hitchcock having made a series of clever tweaks to find new ways of manipulating the audience by making them care. But everything that turned Psycho into an enduring cultural lightning rod originated in Bloch’s novel; the shower scene, the house on the hill, the twist ending and the sense of gothic dread dripping from every moment. The gleeful subversion of conventions that Hitchcock gets all the credit for originated here, and without this book, horror – and cinema – wouldn’t be the same.

7. The Passage by Justin Cronin

Justin Cronin’s epic vampire saga is a sprawling tale of love, loss and societies destroyed, rebuilt and destroyed again, centred not only on characters we could care deeply for, but a slowly growing sense of insidious evil whispering from the shadows, a terror so unknowable that it was always going to lose a little menace once it was explained. But like the best horror writers, Cronin uses that inevitability to make his point – that all too often evil grows from a place that is a little more understandable than we might care to confront. The whole trilogy is fantastic, but for its singular atmosphere of growing dread the first will always be the best.

8. Misery by Stephen King

There’s an intoxicating combination of anger, sadness and catharsis at the heart of Misery; a book written by an author trying to move away from horror only to find that his vast readership wouldn’t accept that. Cue the story of a writer literally held hostage by a fan torturing him into writing what she wants, facilitating the writer’s slow realisation that the genre he was so desperate to move on from may be the only one that’s right for him. It’s an intensely personal and ambivalent book, and one of the best explorations of the highs and lows of creativity ever written.

9. From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell

I don’t know whether it’s cheating to include a graphic novel on this list, but this is a horror masterpiece unlike anything else I’ve ever read, a sprawling, phonebook-heavy exploration of not just the Jack the Ripper murders, but the society that allowed them to happen. Unflinching and harsh, grim and deliberate, the book is an almost forensic dissection of Victorian England, suggesting that the motives for the murders, caused by a collision of dogma, classism and puritanical propriety, were the inevitable result of the true human horrors that made up a seemingly polite society.

10. In the Woods by Tana French

I know; this is not horror, at least not insofar as where it sits in bookstores. But I would also argue it’s not a traditional crime novel or literary character study either. In the Woods uses the structure of a whodunnit to craft one of the most haunting explorations of fear I’ve ever read and, in doing so, includes the only written scene to ever make me jump, a scene so infused with the force of an unshakable nightmare that it transforms the book around it, leaving readers with the sense that some evils can never be truly understood and some trauma is too great to move on from. If that doesn’t encapsulate horror at its most evocative, I have no idea what does.