On December 23, 1951, a six-winged Seraph flew low along the Zambesi at 70 miles an hour, away from the turmoil of the Victoria Falls, leaving behind an apocalyptic chaos of squalor and flames, and launching the astonishing career of

Muriel Spark, whose centenary is celebrated this year. Her story was published in the

Observer, having won their Christmas competition. She was living at the time a Grub Street existence, undernourished and hard up, and the prize was £250, “quite a fortune in those days”. When she saw the advertisement, she recalled in her memoir

Curriculum Vitae (1992),

I put aside my work on Masefield and wrote “The Seraph and the Zambesi” on foolscap paper, straight off. Then I had to type it but found I had no typing paper. I scrounged some from the owner of an art shop nearby in South Kensington, typed it out, put my pseudonym “Aquarius” on the envelope and my name and address inside, and mailed it off to the Observer that afternoon.

This first published work of prose fiction was followed by twenty-two novels and many short stories. It was a lucky start and it introduced her to critics and publishers (including Alan Maclean, the influential editor at Macmillan) and an altogether better class of literary acquaintance than that she had enjoyed through her editorial work at the cantankerous Poetry Society, which she satirizes mercilessly in two autobiographical novels and exposes without the veil of pseudonymity in her memoir. “Pisseur de copie” is the insult with which her one-time lover, Derek Stanford (alias Hector Bartlett), is regularly greeted in A Far Cry from Kensington (1988). Spark admitted that in real life she was a poor judge of men. Her Camberwell landlady, Tiny (Mrs Lazzari in A Far Cry), told her she was a “bad picker”, and Spark agreed. She took her revenge in print. She kept the score, and all her paperwork to prove it.

Centenaries prompt reassessment and new editions. Polygon is publishing all of Spark’s novels in a well-designed and pleasingly coloured format under the leadership of the series editor

Alan Taylor. There are introductions by scholars, friends and fellow novelists which are resolutely up to date, complete with references to Harvey Weinstein and Donald Trump. Spark has unquestionably achieved classic status, but what kind of a classic is she? She founded no movement, and she belongs to none. The general reader is familiar with

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), popularized by stage and screen, and perhaps

The Girls of Slender Means (1963), both short and both dealing with female group behaviour.

The Girls of Slender Means, set nostalgically in wartime London – and as slim and elegant as the Schiaparelli dress which the girls share for their evenings out – has the narrative panache of its predecessor, and a more benign view of most of the girls. Biographers are drawn to

Loitering with Intent (1981) and

A Far Cry from Kensington, with their provocative reflections on the relationship of fact with fiction and their emphasis on the greater veracity of fiction.

Independent and self-reliant, Spark was not an ideological feminist, although she portrayed strong and self-willed women, ranging from school teachers to film stars, abbesses, terrorists and billionaires. Even her admirers (among them Joyce Carol Oates, Ali Smith and Elaine Feinstein) use words such as “arch”, “pert” and “sly” to describe her prose, compliments which some feminists might reject as sexist. Catholics see her as a Catholic writer, but while her work has something in common with that of her supporter Graham Greene, her attitudes to her faith are far from conventional. Frank Kermode (who thought Spark “our best novelist”) describes her religion as “bafflingly idiosyncratic”. She wrote of sin and suffering, liked to split theological hairs, and was particularly drawn to the Book of Job, but many of her portraits of believers are caustic in the extreme. The devout, gullible and multiple-bosomed Mrs Hogg in her first novel, The Comforters (1957), the pig-eyed treacherous convert Sandy Stranger in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, the divinely wicked Abbess of Crewe and her silly flock, and the camp and parasitical Jesuits, Father Cuthbert Plaice and Father Gerard Harvey (scholar of ecological paganism) in The Takeover (1976), do not show the Church in a good light. The whisky priests and tormented adulterers of Greene fare better at the hands of their creator. This can be puzzling to readers of other faiths or none, though Greene, Evelyn Waugh and David Lodge – all fellow Catholics, and all admirers of Spark – do not seem to discern meaningful incongruities between faith and art.

Despite the success of “The Seraph and the Zambesi” in 1951, it took some time for Spark to confirm her new status. The years between her startlingly original Nativity story and the appearance of

The Comforters, published in her fortieth year, were marked by mental anguish, physical ill health and the human “confusion and ferment” that the Seraph so signally lacked. Nevertheless (a word which Spark described as the “characteristic word” of Edinburgh, her birthplace), she displayed throughout this painful time the perseverance which was one of her most distinctive qualities, and managed, with the help of friends and supporters, to emerge from the chrysalis of doubt and paranoia as a more completed figure: mentally, bodily and spiritually transformed. A surprisingly gentle poem that

she wrote at this time, “Chrysalis”, describes “the small violence” of metamorphosis, as the butterfly emerges from the matchbox in which it had spent a London winter, forgotten by those who had saved it.

In his introduction to the Polygon edition of The Comforters, Allan Massie describes the nervous breakdown that preceded her conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1954. “To lose weight and suppress her appetite she took Dexedrine, a then fashionable amphetamine. She began to hear voices . . . .” She also suffered verbal hallucinations, involving crosswords and anagrams and T. S. Eliot, who at one point she believed was posing as a window cleaner in order to pry into the papers of her friends. Massie says “Spark . . . had a need to be in control. In her novels, the narrative voice is always utterly assured. But I suspect that at the time she was scared stiff”. Why, one wonders, did she need an appetite suppressant, if she was undernourished from living on post-war rations of Cornish pasties, cold lamb and beetroot, with the occasional treat of tinned herring roes on toast? Was she simultaneously overweight and half-starved? We know she was plump as a child, and the evidence of A Far Cry is that she was overweight around the time of her conversion. Like her narrator, the young but Rubensesque widow Mrs Hawkins, who was at first “comfortable in her fatness”, Spark took drastic and dangerous measures to get rid of it after “a young woman who I imagine was older than myself once got up in a bus to offer me a seat”.

The Comforters was a promising but puzzling debut. It involves smuggling, blackmail and other of the misdemeanours so common in Spark’s work. The central character, Caroline – a would-be novelist and critic and recent Catholic recruit – is in the throes of paranoia, hearing messages clacking at her from her typewriter, writing her life and her novel for her. The strange and at times jarring tone, and a lack of clarity in Spark’s authorial intentions, are not surprising, given the Slough of Despond from which she had so recently emerged. Her own reservations about this work are expressed in Loitering with Intent, in which her alter ego Fleur knows that she will move confidently onwards to better things once her first publication is behind her.

And so it was to be. Spark excelled, from this time forth, at moving on. Perseverance, which in her later years was to take on the Catholic dimension of Final Perseverance, was her mainstay. Physically and mentally, she would never give up. She was determined to “go on her way rejoicing”. This much-quoted biblical phrase (from Acts 8:39 and Spark’s copy of a translation of Benvenuto Cellini’s autobiography) attributes the stamina and the “rejoicing” to her Catholic conversion. It was her faith, she always maintained, that set her free to become a novelist.

Her second novel, Robinson (1958), is a desert island tale of air wreck, mystery and blackmail, owing something to R. L. Stevenson and Joseph Conrad, and its title to Daniel Defoe. (All her work is studded with intertextual referencing.) It is narrated by a spirited record-keeping young woman, January Marlow, and features credulity, faith and a cat called Bluebell, which January teaches to play ping pong. It is spiked by enigmatic and troubling observations such as “I . . . helped myself to four of Robinson’s share of the cigarettes, to safeguard my soul against the deadly sin of pride. It is really mortifying to do a small mean injury to someone; but a theologian told me once that this is not sound doctrine”. This is not an adventure story: it has more in common with the surreal island narrative of William Golding’s Pincher Martin, which was published two years earlier.

The next three novels, Memento Mori, The Ballad of Peckham Rye and The Bachelors, all set in London, were written and published rapidly between 1959 and 1961, and loiter in a dingy world of rented rooms, spying landladies, geriatric wards, clothing coupons, typing pools, furtive sex and dowdy sherry parties. Memento Mori created a stir with its frank portrayal of the unfashionable subject of old age. Spark writes with zest of dementia, arthritis, heart failure, bedpans, commodes and crutches, and observes with a clinically detached precision the heroic struggles of the elderly to boil a kettle or eat a piece of toast: Percy, gnawing with his few teeth to the last rim of crust comments to his granddaughter that it had been a triumph of “final perseverance . . . the doctrine that wins the external victory in small things as in great”. As in her first novel, a supernatural note is struck by the hearing of voices: famously, a voice on the telephone reminds each character that he or she must die, and indeed many of them do, one of them in an unexpectedly violent way. This is not a particularly mystifying message to those of us who hear it every day, but it seems to surprise and unsettle its recipients. Only one character, Jean Taylor, a patient on the geriatric ward, has come to grips with death: “After the first year she resolved to make her suffering a voluntary affair. If this is God’s will then it is mine”.

More startling than the individually tailored voice of death is the adumbration of Spark’s recurring theme of literary jealousy, in which a husband rages at the reviving fame of his almost forgotten novelist wife, eighty-seven-year-old Charmian. The failure of their writer-son (“Eric was a mess”), and her dislike of and contempt for him, are also vividly drawn. (Spark did not like her only child, Robin, and never had much time for him.) Literary jealousy, in Spark, is more keenly felt than sexual jealousy; she took promiscuity in her literary stride but was strongly drawn to the bitter quarrels of writers. The unexpected revival of literary reputations was also a favourite theme. Her work abounds in stolen, shredded, burned and misappropriated manuscripts. Careers meant much to her.

The Ballad of Peckham Rye is set further down the social scale, among office workers and men of small businesses. Into this lower middle-class backwater walks young Dougal Douglas, with his crooked shoulder and his alleged degree (“I was at the University of Edinburgh myself, but in my dream I’m the Devil and Cambridge”). He has come to study industry and to show the people of Peckham what they are. Spark loved characters who stirred things up, who made things happen. Like Fleur, she did “dearly love a turn of events”. All hell breaks loose in Peckham: fights break out, a bride is ditched at the altar, a woman is stabbed to death by her boring lover, and Dougal disappears to sell tape recorders to witch doctors in Africa. Spark, like Waugh, was fond of packing her characters off to the outback. In one splendid sentence of multiple ironies, Dougal, after stroking the long neck of the shortly-to-be-murdered Merle, had told her that “There is no more beautiful sight . . . than to see a fine woman bashing away at a typewriter”. That was Spark herself: a fine woman bashing triumphantly away at the typewriter which had tormented her and which she had now subdued to her bidding.

In The Bachelors, the catalogue of her investigations into dubious and criminal activities is extended to embrace forgery, false pretences, the planning of a perfect murder, and “fraudulent conversion”, a phrase which she makes to resonate. Again, blackmail pervades the plot. It is a novel of backstairs dealings, séances and loneliness: one of the bachelors sits in his club “looking as lonely as possible in the hope that someone married would take him home to supper”. Its demonic figure is the fake medium, Patrick Seton, whose name, as James Campbell points out in his introduction, half-rhymes with Satan (and recalls Seyton, Macbeth’s last faithful servant). Spark was to create a long sequence of malevolent catalysts, which includes the “oldest friend” cuckoo-in-the-nest Billy in The Public Image (1968), Lister the stage-managing butler in Not To Disturb (1971), the elusive Robert Leaver in Territorial Rights (1979), Luke, the elegant spare time “graduate waiter” in Symposium (1990), and Marigold, the earnestly destroying daughter in Reality and Dreams(1996). Servants, in Spark’s novels, are rarely to be trusted, and she deplored earnestness.

The Bachelors is downbeat, and Spark’s readers may have thought she would linger forever in the gloomy suburbs of petty crime. But her next novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, was a great leap forward. Her only novel to be set wholly in Scotland, it is short, bright and supremely confident: a compact classic. The well-known story follows Miss Brodie’s girls, the crème de la crème, from childhood through puberty to sex, marriage, and in some instances, death. It is notorious for its high-handed, proleptic manner, its Olympian omniscience, as Spark foretells fate more accurately than Jean Brodie, who gets most things wrong. It is easy for Spark to manipulate the destinies of her characters, because, as she often reminds us, she made them all up, and they must do as she dictates. Not for her the contemptible and sentimental fallacy that characters have a will of their own.

The omniscient mode invites resistance. How are we meant to respond to the death by fire of Mary MacGregor, who is so frequently foreshadowed from the second chapter of Jean Brodie onwards, as she runs again and again, choking, hither and thither along a hotel corridor in Cumberland? Pity is pre-empted by the narrative mode, although her school friends, when they meet in later years, sometimes reflect they wish they “had been nicer to Mary”. It’s hard to weigh the moral content of that reflection. Pity seems largely irrelevant in Spark’s novels, as she blithely forfeits one of the novelist’s stocks-in-trade. The reader cannot help but worry at times about the status and representation of a character: is the portrayal satirical, objective, contemptuous, admiring, or sympathetic? There is very little guidance, and critics are sharply divided. Events play themselves out as though watched by God from a very great distance and another timescale. Lord, what fools these mortals be. The author spies upon her creations, and lets them hurtle towards disaster. Maybe she sees herself as God’s spy, observing with amusement the scurrying antics of a fallen world. Alberto Manguel, who admires Spark, believes that “writers bring about a wild form of justice in their role as God’s spies”, and perhaps that wild justice is her aim.

Appalling and sometimes ridiculous sins and crimes dominate novel after novel: where, some critics have plaintively asked, are the “nice” characters, whom we may be allowed to like, and for whom we may weep? The crimes her work encompasses are startling in their aggregate, and the headcount spectacular. First there are the African shootings: the short story “Bang Bang You’re Dead” is based on a real-life incident, when a red-headed school friend from Edinburgh, Nita McEwan (who happened to bear a curious resemblance to the red-haired Spark) was shot dead by her husband in the hotel in Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) where Spark was living. Spark at this time was twenty-one, with a newborn baby, living in a land where most men and some women kept a gun by the bedside and crimes passionnels were commonplace.

As Spark’s fiction moves to Britain, and later to New York and Continental Europe, we encounter the malicious doctoring of photographs, spying on many levels both official and personal, snooping and voyeurism, plane and car and train crashes, death by lightning, deaths in care homes and nunneries, strangulation and smuggling. The cast of villains includes murderers, impostors, robbers, thieves, burglars, terrorists, kidnappers, con men, charlatans, quack doctors, fake fortune-tellers, fakers of miracles, and fake psychics. Anonymous letters and phone calls – some supernatural, others explicable – proliferate. Private detectives (“shadows”) with dark agendas abound, as do believers in miraculous remedies. (After Dexedrine, Spark was prescribed Largactil, still known to pharmacists as the “chemical cosh”, which, oddly, seems to have been a help to her.)

Ali Smith, in her useful preface to The Abbess of Crewe (which tells us that the globe-trotting nun, Sister Gertrude, was based on Henry Kissinger) gives an account of Spark’s wartime work as an employee of the “Newsroom of the Political Intelligence Department”, dispensing Black Propaganda to the Germans to persuade them they had already lost the war. This experience of official duplicity (which Spark set out in hallucinatory detail in The Hothouse by the East River, 1973) seems to have coloured her imagination for life. Unlike Angus Wilson, who tried to put his unhappy experiences of Bletchley Park behind him, she returns again and again to the theme of spying and treachery. This scandal was close to home: Alan Maclean, her early editor, was the brother of Donald Maclean, who defected in 1951. Espionage and treason provide the subtext for many of her works. Human nature, Spark insists, is universally venal and base.

Two short novels were followed by her longest, which strikes a very different note. Set in Israel in 1961, The Mandelbaum Gate (1965) tackles huge questions of identity and faith. Judaism and Catholicism and Zionism and Arab nationalism clash in it like tectonic plates and its effect is deeply disquieting. Like Spark, the protagonist Barbara Vaughan is half Jewish and half British, though in her case it is her mother who is Jewish, which makes her more Jewish than Spark. (Barbara’s English grandmother makes cucumber sandwiches, her Jewish grandmother makes cucumber pickle; her father, denounced for having married a Jew, at least manages to meet “an indigenous death” while fox hunting.) Barbara is on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and to examine her conscience as to whether, as a Catholic convert, she may marry her lover – an ugly, divorced, lower-middle-class archaeologist working on a dig over the border in Jordan. She becomes accidentally involved with Middle Eastern politics and espionage, and hostage to conflicting interests. But it is her spiritual life and her state of mind that are so perplexing, to herself and to the reader, as she struggles with her sense of herself as “a Gentile Jewess, a private-judging Catholic, a shy adventuress”. She is searching for a life that is “unified under God”, but finds only deeper and deeper confusion.

In two extraordinary pages at the centre of the novel, we find her wondering whether to go to Nazareth or the Tomb of David, but goes instead (as did Spark) to the Eichmann trial. What kind of a choice was that? In the courtroom, her stream of consciousness moves from trying to comprehend the proceedings to comments on the French nouveau roman and “the new irrational films which people can’t understand the point of . . .”. It is painful to the reader to follow Barbara’s thoughts. At the end of the book, her doubts about her marriage are solved by the annulment of her lover’s marriage through some implausibly casuistic technicality, approved by the Vatican, involving a forged baptismal certificate. The reader’s doubts as to the purpose and nature, indeed the genre of this novel, remain unresolved. Fevered and earnest, it seems to hint at breakdown and despair.

But despair was not what came next. Maybe the writing of this confusing book was therapeutic, for Spark was to surge on, rejoicing, to write fourteen more novels, some of them very short and very funny. Literary and worldly success suited her, transforming her into the well-groomed woman of her middle and later years, connoisseur of haute couture, fine food and social nuance, and fierce custodian of her public image. The Public Image and The Driver’s Seat (1970) breathe a freer and more confident air. The first, set in Rome, is a knowing portrait of the film milieu, complete with drugs and orgies and an English film star who is adept at publicity and survival. Spark has by now perfected the art of the epigrammatic throwaway: in a joyous and in every way politically incorrect passage, she describes a motley group of translators, antique restorers, actor-painters, architect-guitarists, and a “male Eskimo called Gigo whose job ended at that”. The Driver’s Seat is an equally highly coloured, indeed lurid, thriller with a protagonist successfully intent on getting herself murdered – a storyline which has understandably provoked feminists. There is much emphasis on appearances and consumerism, and Andrew O’Hagan unforgettably tells us that his research into Spark’s archive in Edinburgh revealed that in 1969, during the novel’s eight weeks of composition, she shopped extravagantly in Florence for expensive blouses, shoes, an evening suit, a white coat, and acquired a hairpiece from Elizabeth Arden for 50,000 lire. She also ordered Black Orchid and Coffee Tone pantyhose for postal delivery. There are dangers in keeping the paperwork.

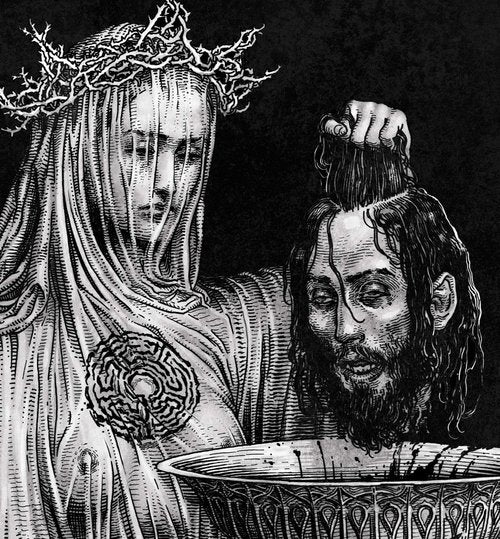

Spark was in the driver’s seat now. In her fiction she often uses that metaphor, though in her later years her friend and companion Penelope Jardine did most of the driving. Books poured from her: black comedies, autobiographical memoirs, theological meditations on suffering and sin. Not To Disturb is a Gothic melodrama set in a castle in Geneva; Symposium, with a wonderfully intricate time scheme, centres on a smart and disastrous Islington dinner party, where the guests include a melancholy gay man who can “talk to a tree” and a red-haired Scottish witch. Her final novel, The Finishing School (2004), turns on literary jealousy pursued almost to the death, and involves a red-haired teenage would-be genius: it ends surprisingly well. Aiding and Abetting (2000) tells the story of Lord Lucan who murdered the nanny instead of the wife and is pursued by a doppelgänger, with shades of James Hogg’s Confessions of a Justified Sinner. The two Lords Lucan, real and false, have as their psychoanalyst a woman who in a previous life had faked stigmata with her menstrual blood; there is a lot of blood in this novella, and Spark likes to point out that being “washed in the blood of the Lamb” must have been an unpleasantly sticky experience. I had lunch with her in London when she was planning this novel, and as she talked about it she was animated by a creative glee that few writers in their eighties may hope for.

In these late novels, great wealth frequently appears as a deus ex machina, giving freedom of movement to the good and the bad alike. We encounter this device in The Hothouse by the East River, set in Manhattan, where the ghostly Elsa shops and drinks and visits her analyst and flits back and forth to Zurich; in Symposium, where Monets and flats in Hampstead are handed out as wedding presents; in Reality and Dreams, where a film director’s rich and tolerant wife allows him a lifestyle of unconstrained comfort and luxury, albeit in Wimbledon. Spark enjoyed exploring these realms of gold, and was pleased that she no longer had to spend time in the kitchen, pretending to be domestic: as soon as she could afford to pay caterers, she did so, and manifested litigious indignation when Hilary Spurling in her biography of Paul Scott claimed, in a friendly manner, that she used to cook dinner for her guests.

The most serious confrontation with money as subject occurs in The Takeover, whose anti-heroine bears the Jamesian name of Maggie. The setting is Italy in 1973. Billionaires sense “a change in the meaning of property and money. They all understood these were changing in value, and they talked from time to time of recession and inflation, of losses on the stock market . . . of hedges against inflation”. That’s a very early and astute fictional reference to a hedge fund. The unimaginably wealthy and intermittently generous Maggie, hemmed in by security guards and bodyguards and preyed on by friends, is swindled out of her fortune by a charming financial adviser who produces “an appealing global plan” for Maggie’s fortune. The plan is unfathomable to Maggie, but she believes she is doing the right thing, until it is too late. The book, unsatisfactory in some ways, may be read as a foreshadowing of the financial crash of 2008.

The sum of Spark’s output remains ambiguous to me, and to others. There is a consensus of praise round the pivotal Jean Brodie, but little else. Some consider The Abbess of Crewe her masterpiece, but it strikes me as lightweight and overrated, with a playfulness that does not match its subject. I have deeper difficulties with her views of good and evil, of grace and sin and stupidity, and I continue to worry about the manner in which she disposes of her characters. It’s not that I want them to be nice: she roundly repudiated a critic’s view that her characters were “nasty” by affirming that they were worse than nasty – they were insufferable and outrageous. What worries me more is a discomfort, an uncertainty, about her intentions. In his review in New York magazine of Loitering with Intent, Michael Holroyd argued that “If this novel seems to you light or harsh or amoral or overdetached, then this is perhaps how it should seem, since it is ostensibly written by someone who calls herself harsh and treats a story ‘with a light and heartless hand, as is my way when I have to give a perfectly serious account of things’”. The layers of defensive irony and displacement here are almost impenetrable, as they are meant to be.

Martin Stannard’s biography, published in 2009, was initiated and authorized by Spark, but then contested by her. One of Stannard’s many anecdotes tells us that at a talk in City College in New York in the mid-1960s someone put it to her that she did not much like the people she wrote about. “Oh no”, Spark replied, “I love them all; when I’m writing about them I love them most intensely, like a cat loves a bird. You know cats do love birds; they love to fondle them.” She was enigmatic from first to last, a smiling assassin.