|

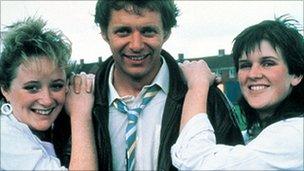

| Jean McConville with two of her children shortly before her disappearance. |

My hero:

Jean McConville

by Amanda Foreman

J

|

| Jean McConville with two of her children shortly before her disappearance. |

J

|

| William Beveridge addressing a group of housewives, 1944. Photograph: Hans Wild |

I

n 1942 William Beveridge's report on social insurance was a national bestseller: with memories of the 30s still vivid, wartime Britain had an enormous appetite for the promise that the postwar world would be different. The scant support for millions locked, through no fault of their own, in the "five evils" – want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness – had been a disgrace. There had to be change.

V

Dunbar came from that part of Bradford's tough Buttershaw estate known as "the Arbor". Barnard has interviewed Dunbar's family, friends and grownup children and then got actors to lip-synch to the resulting audio soundtrack, talking about their memories. Passages of Dunbar's autobiographical plays are acted out in the open spaces of the very estates where she grew up, surrounded by the (presumably real) residents looking on. The effect is eerie and compelling: it merges the texture of fact and fiction. Her technique produces a hyperreal intensification of the pain in Dunbar's work and in her life, and the tragic story of how this pain was replicated, almost genetically, in the life of her daughter Lorraine, who suffered parental neglect as a child and domestic violence and racism in adult life, taking refuge in drugs in almost the same way that Andrea took refuge in alcohol. The story of Lorraine's own child is almost unbearably sad, and the experience of this child's temporary foster-parents – who were fatefully persuaded to release the child back into Lorraine's care – is very moving.

Dunbar's story, and her success as a teenage playwright in Max Stafford-Clark's Royal Court, challenges a lot of what we assume about gritty realist theatre or literature from the tough north. In many cases, it is produced by men whose gender privileges are reinforced by university, and who have acquired the means and connections to forge a stable career in writing. However grim their plays or novels, there is a kind of unacknowledged, extra-textual optimism: the author, at least, has got out, has made it. Dunbar hadn't got out; she did not have the aspirational infrastructure of upward mobility. In the end, she was left with precisely those problems she depicted. Barnard has created a modernist, compassionate biopic: a tribute to her memory and her embattled community.

THE GUARDIAN

|

| Andrea Dunbar |

Innovative documentary The Arbor uses lip-synching techniques to give life to audio interviews telling the story of tragic playwright Andrea Dunbar.

The raw, working-class realism of 1986 film Rita, Sue and Bob Too - written by Dunbar and set on Bradford's Buttershaw estate - has helped to make it a cult classic.

Her story of the friendship between two schoolgirls who begin an affair with a married man was straplined: "Thatcher's Britain with her knickers down."

"I really love the film, I really love the friendship between the two girls, I really love the fact that it doesn't really moralise about them enjoying sex," says the documentary's director Clio Barnard, also from Bradford.

"But I suppose I didn't really know much about Andrea so I hadn't really realised where that writing came from, or where that talent came from, and I didn't know her plays."

The director's journey of discovery began with visits to the Buttershaw estate and Dunbar's street, Brafferton Arbor, to meet those who knew the writer - a heavy drinker who died of a brain haemorrhage in 1990, aged 29.

Interviews were recorded "to create a sort of a screenplay that you listen to rather than read".

Insightful reminiscences from figures from the writer's past - and two of the three children she had with three different fathers - are brought to life by actors who mime along.

"The actors did a phenomenal job because they had to learn it like a piece of music - technically it's very challenging," says Barnard, 45.

"In addition, they had to give a nuanced performance so I think they really did a remarkable job."

The "verbatim" technique used by Barnard was partly inspired by Dunbar's ear for raw dialogue that is such a central part of her autobiographical writing style.

"Part of what I really like about Andrea's writing is it uses peoples words as they say them, that it's verbatim - it felt important that it was in people's own words."

As Barnard's unique documentary progresses, the focus shifts from Andrea to what became of her eldest daughter, Lorraine, now 29 - the age her mother was when she died.

The interviews with Lorraine, a former drug addict, were recorded in prison where she was serving a sentence following the accidental death of her two-year-old son, who died after ingesting drugs.

Lorraine's interviews in The Arbor - mimed by actress Manjinder Virk - show that she shares Andrea's way with words, succinctly putting across her feelings about her mother's work, her bitter childhood memories and her own troubles.

"I think she can talk about very complex, difficult things, very directly with very few words - I think she's got a real gift for that," says Barnard.

Lorraine's younger sister Lisa, whose voice is also prominent, says watching actress Christine Bottomley mouth her words was "very strange - I had to keep pinching myself 'cos I thought it was me".

Lisa - who was 10 when Andrea died - has a more idolized view of her mother than sister Lorraine, who she says she has not spoken to for years.

"She used to always write at night-time in her bedroom," she remembers.

"In the morning, you'd go in and there'd be a little bedside bin and it would just be full of screwed-up paper."

Her abiding memory of the first time she watched Rita, Sue and Bob Too is of feeling "disgust at all the swearing".

"When I was 14, I saw it for the first time and everyone at middle school had seen it at about that time and everybody wanted to talk to me and sit near me."

Although Andrea Dunbar's masterpiece was made into a film by Scum director Alan Clarke in 1986, it was originally performed as a stage play - the writer's second - four years earlier.

Barnard's documentary is interspersed with both archive footage and excerpts from a modern-day performance of her first play - also called The Arbor.

Her debut work - which she began as part of a school project - was premiered at London's Royal Court in 1980 after her raw talent was spotted by theatre director Max Stafford-Clark.

Like Rita, Sue and Bob Too, it explores themes familiar to Andrea including abusive relationships, teenage pregnancy and alcoholism.

For the treatment featured in the documentary, open auditions were held on the Buttershaw estate ahead of an open-air performance to residents of the Brafferton Arbor.

The cast is led by former Buttershaw resident Natalie Gavin - a theatre studies student at Huddersfield University - who gives a wholly believable performance as a young Andrea.

Gavin, 23, says the atmosphere while filming the play on Brafferton Arbor was "kinetic" because residents "were involved in it and they were allowed to be in it, and it made it magic".

She says her involvement is fated because of the connections she shares with Andrea - they went to the same school and her father lived on Brafferton Arbor where he knew Andrea.

"I want to pursue my talent and she wanted to pursue hers," she says.

"She went out there and did it and that's exactly what I'm doing, through her, as well as being in her surroundings."

For Andrea's youngest daughter Lisa, meanwhile, the project has been "amazing - weird, but in a good way".

"I'm very proud of my mum.

"When I was younger, nobody really spoke about the film but, after she died and I understood more, it was like: 'That's her whose mum wrote Rita, Sue and Bob Too.'

"The only thing that upsets me is that she's not here to have this fame for herself.

"She didn't get much fame when the film first got released - it's after her death that it's all taken off."

|

| Stanley Spencer . . . 'In painting after painting he made a paradise of Cookham, which in reality is no such thing.' Photograph: John Pratt |

I