In 1953, literary history—acting through the good offices of Edna Ward, of Wellesley, Massachusetts—brought together two of the most gifted, and least similar, American poets of the postwar era. Mrs. Ward was the mother-in-law of Richard Wilbur—at the age of thirty-two, the author of two acclaimed books of verse—and a friend of Aurelia Plath, whose twenty-year-old daughter, Sylvia, had just endured the hellish summer she later chronicled in “The Bell Jar.” Wilbur was invited, as he wryly recalls in his poem “Cottage Street, 1953,” “to exemplify / The published poet in his happiness, / Thus cheering Sylvia, who has wished to die.” Of course, Wilbur’s good will could not make a dent in Plath’s misery: he describes himself as “a stupid lifeguard” who finds “a girl … immensely drowned.” But the meeting was productive in another way: decades later, after Plath had written, died, and become a myth, it offered Wilbur a test and an emblem of his own, very different poetic calling.

In his poem, Wilbur slyly turns Mrs. Ward’s polite inquiry about tea—“if we would prefer it weak or strong”—into a literary and moral question. Plath, of course, preferred it strong, in art and in life; she would go on, in Wilbur’s words, “to state at last her brilliant negative / In poems free and helpless and unjust.” But where does this leave Wilbur, whose poems are brilliantly affirmative, and who has enjoyed all the blessings Plath did not—longevity, reputation, worldly success? Does the fact that he was destined for happiness condemn his poetry to be weak, the tepid milk to Plath’s acrid lemon?

The question Wilbur asks in “Cottage Street, 1953” has been posed by critics since the beginning of his career—starting with Randall Jarrell, whose review of Wilbur’s second book, “Ceremony,” complained that Wilbur “never goes too far, but he never goes far enough.” And it echoes from beginning to end of the “Collected Poems 1943-2004” (Harcourt; $35), which will be Wilbur’s monument. How does a poet who feels himself, in the words of an early poem, “Obscurely yet most surely called to praise” practice that calling in an age when poetry is overwhelmingly drawn to crisis, confession, and complaint?

This is more than just a matter of literary fashion, though in Wilbur’s public statements one can often sense his impatience at being typecast as the placid straight man to his wilder contemporaries—above all, Robert Lowell. Lowell and Wilbur made their poetic débuts in the same postwar moment; Lowell’s “Lord Weary’s Castle” won the Pulitzer Prize in 1947, the year that Wilbur’s “The Beautiful Changes” appeared. And it was Lowell, much more than Plath, whom critics perpetually used as a foil when describing Wilbur. In a 1964 interview, Wilbur ruefully recited the standard contrast: “I’m all grace and charm and short gains, and he’s all violence and … Well, he’s Apollo and Dionysus locked in a death grip.”

Lowell, like Plath, John Berryman, and countless lesser poets, wrote about and out of a spiritual turmoil that amounted to, or resulted in, madness. Writing about his experience in a psychiatric ward in “Waking in the Blue,” from his hugely influential 1959 book “Life Studies,” Lowell insisted on the dangerous and pathetic majesty of the mad: he writes of Stanley with his “kingly granite profile,” of Bobbie, “a replica of Louis XVI / without the wig.” Wilbur’s poem “Driftwood,” by contrast, declares his own allegiance to “emblems / Royally sane,”

Which have ridden to homeless wreck, and long revolved In the lathe of all the seas, But have saved in spite of it all their dense Ingenerate grain.

Wilbur has always been conscious that his particular poetic gifts and spiritual resilience were untimely. He started writing, as he later recalled, “for earnest therapeutic reasons during World War II,” in an effort to bring the sanity of art to bear on “a personal and an objective world in disorder.” (Wilbur served as a front-line infantryman in Europe, after his reputed radicalism got him kicked out of Army cryptography training.) The poems of his first book treat his war experiences in a style so elaborately formal that the most awful subjects are sublimated into irony, or even black comedy. There is something deliberately, monstrously cartoonish about “Mined Country,” where “Cows in mid-munch go splattered over the sky.” The persistence of the mines—“Danger is sunk in the pastures … / Ingenuity’s covered with flowers!”—is Wilbur’s way of writing about the persistence of the war itself, with all its psychic casualties: “it’s going to be long before / Their war’s gone for good,” he soberly predicts.

But in this poem, as throughout “The Beautiful Changes,” Wilbur’s style, influenced by the estranging precision of Marianne Moore and the courtly ironies of John Crowe Ransom, makes disorder almost parodically articulate. Surely there has never been a more aestheticized vision of K.P. than Wilbur’s in “Potato”:

Scrubbed under faucet water the planet skin Polishes yellow, but tears to the plain insides; Parching, the white’s blue-hearted like hungry hands. All of the cold dark kitchens, and war-frozen gray Evening at window; I remember so many Peeling potatoes quietly into chipt pails.

Randall Jarrell, whose experience of military life was much milder than Wilbur’s (he served at a Stateside airbase), was far more willing to admit the sorrow and pity of war into his poetry. There is nothing in Wilbur that resembles Jarrell’s defiant matter-of-factness in “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner”: “When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.”

But then, as Jarrell wrote, “The real war poets are always war poets, peace or any time”; and the same holds true of peace poets, in whose company Wilbur confessedly belongs. In “Up, Jack,” Wilbur looks to Falstaff as a tutelary spirit for the postwar world, “a god / To our short summer days and the world’s wine.” Wilbur’s refined epicureanism is far removed from Falstaff’s grossness, but the poet dares, like the fat knight, to make an ethic of enjoyment. There is something quietly polemical about Wilbur’s proud adoption-by-translation, in “Ceremony,” of La Fontaine’s “Ode to Pleasure”:

For games I love, and love, and every art, Country, and town, and all; there’s nought my mood May not convert to sovereign good, Even to the gloom of melancholy heart. Then come; and wouldst thou know, O sweetest Pleasure, What measure of these goods must me befall? Enough to fill a hundred years of leisure; For thirty were no good at all.

Such praise of mundane joys defies the predominant trend of English and American poetry since Eliot, if not since Wordsworth. Against the potent myth of the Romantic poète maudit—the glamorous lineage of Chatterton, Shelley, Keats, Rimbaud, and Hart Crane, fatally revived in Wilbur’s own time by Plath, Lowell, and Berryman, among others—Wilbur sets the unfamiliar ideal of the poète bénit. In a 1977 Paris Review interview, he specifically rejected the tragic glamour of a Berryman, who had compared writing to surgery: “I am obliged to perform in complete darkness / operations of great delicacy / on myself.” Berryman, Wilbur said, “was such a very hard worker that he lived almost entirely within his profession… . The impression one is left with is of a man who is working desperately hard at his job. Well, I admire that, but I think it can break your health and destroy your joy in life and art.”

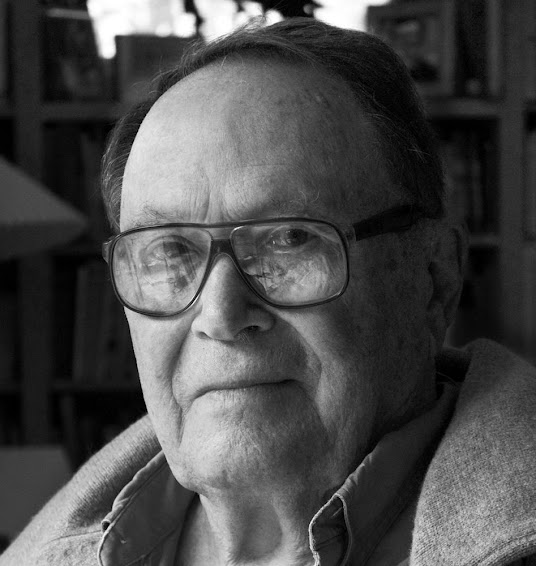

Throughout his long career, Wilbur has remained committed to that ideal of “joy in life and art,” and has been amply rewarded with achievement and honors in both spheres. After the Army and a stint in graduate school, Wilbur—like most poets of his generation—earned his living as a college professor. Unlike the teaching careers of many poets, though, his was marked by long and steady tenures: twenty years at Wesleyan University, then a further ten at Smith College. He was just as warmly embraced by the institutions of literary life. Born in 1921, he won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award in 1957 (for his collection “Things of This World”), received the first of many honorary doctorates in 1960, and in 1987 was appointed United States poet laureate; he received a second Pulitzer in 1989 for his “New and Collected Poems,” which this “Collected Poems” supersedes. He has also enjoyed success in the theatre, as a translator of the plays of Molière and as the lyricist for Leonard Bernstein’s operetta “Candide.” All this seems highly becoming to a poet of fruitful activity, not barren speculation.

Wilbur’s position was often a lonely one, however, in a period that tended to view all affirmation as mere bourgeois complacency. One can get a good idea of the literary climate in which Wilbur began to write from Lionel Trilling’s great study “Sincerity and Authenticity,” published in 1972. Trilling suggests that English literature from Shakespeare to Henry James had agreed on an ideal of earthly life, on the reward that awaits characters who live “happily ever after.” This is the worldly felicity promised by the goddess Juno in “The Tempest”: “Honour, riches, marriage blessing, / Long continuance and increasing.” “It has to do,” as Trilling says, “with good harvests and full barns and … affluent decorum.” But “in the literature of our own day,” Trilling goes on to argue, “the visionary norm of order, peace, honour, and beauty has no place.” Both writers and readers instinctively meet it with “bitter contemptuous rejection,” whether out of “despair over the impossibility of realizing the vision” or out of a profoundly modern disbelief that any earthly happiness could satisfy the needs of the spirit. Rather than worldly completeness, the twentieth-century mind seeks in literature “the disintegration which is essential if it is to develop its true, its entire, freedom.”

Strangely enough, the whole course of Trilling’s argument—right down to the image of “good harvests and full barns”—was anticipated, and disputed, by Wilbur in a poem from his 1956 collection, “Things of This World.” In “Sonnet,” Wilbur offers a characteristic response to the problem of the “happily ever after”:

The winter deepening, the hay all in, The barn fat with cattle, the apple-crop Conveyed to market or the fragrant bin, He thinks the time has come to make a stop, And sinks half-grudging in his firelit seat, Though with his heavy body’s full consent, In what would be the posture of defeat, But for that look of rigorous content.

Worldly satisfaction, Wilbur acknowledges, can have the look of defeat, because it means that there is nothing more to aspire to. He insists, though, that what looks like defeat should really be understood as contentment, the only contentment available in this world: of labor completed, tasks achieved, the future secured. Still, in the last lines of “Sonnet,” he acknowledges that the weary, satisfied farmer always remains haunted, even reproached, by another figure—the scarecrow that stands in the field, “floating skyward its abandoned hands / In gestures of invincible desire.”

Wilbur is too honest a poet to deny the persistent glamour of the scarecrow’s yearnings; but his instincts are all on the side of the farmer’s contentment. And throughout his “Collected Poems” Wilbur is generally uncomfortable when he tries to imagine discontent, or what Trilling called “disintegration.” From time to time over his long career, Wilbur has attempted poems of comprehensive moral statement, which aim to do justice to the horror of the modern world. But these poems are among his least convincing, because his invocations of evil seldom avoid seeming merely dutiful. Certainly, this is the case in “On the Marginal Way,” from his 1969 collection “Walking to Sleep.” The poem begins with a walk on a beach that becomes a scene of horror:

The rocks flush rose and have the melting shape Of bodies fallen anyhow. It is a Géricault of blood and rape, Some desert town despoiled, some caravan Pillaged, its people murdered to a man.

It is typical of Wilbur that this murderous vision should be, precisely, a vision, a mirage. Indeed, what Wilbur sees is twice removed from reality: the rocks remind him not of “blood and rape” themselves but of “a Géricault,” an already aestheticized violence. And while Wilbur goes on to invoke “Auschwitz’ final kill,” the poem does not take account of that evil in such a way that the memory of evil would affect the imagination of good. Instead, in its last stanzas, “On the Marginal Way” turns away from evil altogether, in order to receive an unaccountable consolation:

And like a breaking thought Joy for a moment floods into the mind, Blurting that all things shall be brought To the full state and stature of their kind.

This sort of joy is not so much the conclusion to an argument as a complexion of the mind. As he explained in the Paris Review interview, “To put it simply, I feel that the universe is full of glorious energy, that the energy tends to take pattern and shape, and that the ultimate character of things is comely and good. I am perfectly aware that I say this in the teeth of all sorts of contrary evidence, and that I must be basing it partly on temperament and partly on faith, but that is my attitude.”

If Wilbur’s essentially hopeful temperament leaves him ill-equipped for certain kinds of moral inquiry, however, it is also the source of his enormous poetic gifts. No other twentieth-century American poet, with the possible exception of James Merrill, demonstrates such a Mozartean felicity in the writing of verse. This is partly a matter of formal mastery: Wilbur has written the best blank verse of any American poet since Frost. Yet Wilbur’s formal poetry never has the slightly defensive tone that afflicts many writers of formal verse in this era of free verse. Just as his spirit takes naturally to “rigorous content,” so his musical imagination takes naturally to contented rigor. “I have no quarrel at all with Emerson,” he has remarked. “He said, ‘not meter, but a meter-making argument makes poetry,’ and I think that’s true. I simply write a kind of free verse that ends by rhyming much of the time.”

This seeming paradox is actually a key truth about Wilbur’s genius: for him, the conventional is organic. More than a matter of verse technique, this is the theme and argument of some of his best poems. In “A Baroque Wall-Fountain in the Villa Sciarra,” Wilbur contrasts two Italian fountains that are also two ways of being in the world. The Baroque fountain of the title is a triumph of fantastic ingenuity, all shells and fauns and cherubs: “More addling to the eye than wine, and more / Interminable to thought / Than pleasure’s calculus.” But the poet cannot quite dismiss the suspicion that art should be more than just delightful: “Yet since this all / Is pleasure, flash, and waterfall, / Must it not be too simple?” Maybe, he wonders, there is more truth and more honesty in “the plain fountains that Maderna set, / Before St. Peter’s,” whose simple aspiring jet is a legible emblem of Romantic yearning and disappointment: “the main jet / Struggling aloft until it seems at rest / In the act of rising, until / The very wish of water is reversed.”

There is no doubt which of these two fountains appears more “modern,” in Trilling’s sense. But Wilbur finally declares his preference for the Baroque fountain, whose fauns, “at rest in fulness of desire / For what is given,” seem to promise that a complete happiness is possible on earth. And in poem after poem Wilbur finds new metaphors with which to assert that—to quote the title of his best-known poem—“Love Calls Us to the Things of This World.” In “A Black November Turkey,” he praises “the cocks that one by one, / Dawn after mortal dawn, with vulgar joy / Acclaim the sun”; in “After the Last Bulletins” the garbage-collectors, “saintlike men, / White and absorbed, with stick and bag remove / The litter of the night.” The most famous of these emblems is the clean laundry of “Love Calls Us,” in which the sight of sheets and smocks calls forth a secular prayer: “Oh, let there be nothing on earth but laundry, / Nothing but rosy hands in the rising steam / And clear dances done in the sight of heaven.”

The profusion of such emblems in Wilbur’s “Collected Poems” is more than just a proof of his talent for metaphor. It is the poetic fruit of his distinctive metaphysics, which deserves the old-fashioned name of Transcendentalist. The condition of metaphor is the capacity of things to be likened to one another; and for Wilbur this very capacity suggests that all things share the same essential nature. “I think that all poets are sending religious messages,” he once declared, “because poetry is, in such great part, the comparison of one thing to another; or the saying, as in metaphor, that one thing is another. And to insist, as all poets do, that all things are related to each other, comparable to each other, is to go toward making an assertion of the unity of all things.” This faith in what he calls, in a late poem, “the dove-tailed world” is clearly inspired by Emerson, who wrote in “The Poet,” “Things admit of being used as symbols because nature is a symbol, in the whole, and in every part.”

This intuition provides Wilbur with his motive for metaphor: “What should we be without / The dolphin’s arc, the dove’s return, / These things in which we have seen ourselves and spoken?” And the happiest of Wilbur’s many happy gifts is his confidence that we do, indeed, see ourselves in nature, that the human being is profoundly at home in this world. That confidence is what makes possible the hundreds upon hundreds of brilliant images and observations that light up Wilbur’s “Collected Poems”: “a still crepitant sound / Of the earth in the garden drinking / The late rain”; “Slow vultures kettling in the lofts of air”; “the shucked tunic of an onion, brushed / To one side on a backlit chopping-board / And rocked by trifling currents, prints and prints / Its bright, ribbed shadow like a flapping sail.”

It is up to the “temperament and faith” of each reader to decide whether the golden world of Richard Wilbur’s poetry is the real world. What is certain is that Wilbur has given his vision the permanence, the immediacy, and the conviction of major poetry. His “Collected Poems” has the same moving and ambiguous power that he ascribed, in an early poem, to yet another fountain, this one in “Caserta Garden”:

A childhood by this fountain wondering Would leave impress of circle-mysteries: One would have faith that the unjustest thing Had geometric grace past what one sees.

Published in the print edition of the November 22, 2004, issue.

Adam Kirsch is a poet, a critic, and the author of, most recently, “Who Wants to Be a Jewish Writer?”

THE NEW YORKER