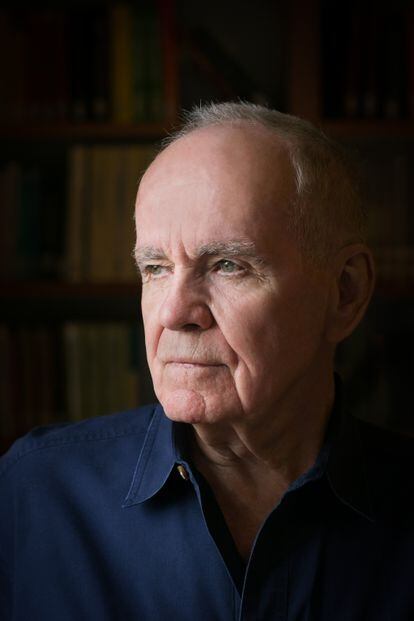

Cormac McCarthy in 2014.BEOWULF SHEEHAN

American novelist Cormac McCarthy’s long-awaited return

‘The Passenger’ and its sequel ‘Stella Maris’ are brilliant and sometimes exasperating explorations of incest, mental illness, science and philosophy by the Pulitzer-winning author of ‘The Road’

Eduardo Lagos

November 4, 2022

Nearly 20 years ago, Cormac McCarthy joined the prestigious Santa Fe Institute, a theoretical research institute populated by scholars and researchers in fields such as theoretical physics, linguistics, astronomy and mathematics. McCarthy was the only writer in residence. For years, McCarthy could be heard typing away on his blue Olivetti Lettera 32, until one day he decided to put it up for auction at Christie’s. The antiquated typewriter sold for more than $250,000, which McCarthy later donated to the institute. The writer, who has always eschewed hobnobbing with his peers, is happier hanging out with scientists. Instead of novels, his bookshelves are filled with scholarly tomes like The Foundations of Mathematics, published in 1931 by Frank Ramsey, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s protégé.

Shortly after arriving at the Santa Fe Institute, McCarthy published No Country for Old Men (2005) and The Road (2006), his last two novels until he broke a 16-year hiatus in October with The Passenger. Its sequel, Stella Maris, will be published in November. Both novels tackle scientific themes that have long fascinated McCarthy.

McCarthy has always been drawn to people driven by dark forces who choose to live dangerous lives

Cormac McCarthy was born 89 years ago in Providence, Rhode Island, the hometown of H. P. Lovecraft. Despite the profound differences between the two writers, they subtly share the same perception of the underlying horror of human existence, and our capacity to harbor and perpetrate evil. Although his father was a wealthy lawyer, McCarthy was never much interested in the complacency of a comfortable and secure life. Rather, he has always been drawn to people driven by dark forces who choose to live dangerous lives on the fringes of society. McCarthy served in the US Air Force as a pilot for four years, and has always loved poker and car racing.

His first few novels were set in the breathtaking beauty of the Tennessee countryside and the haunting urban landscapes of Knoxville (eastern Tennessee), where he spent his childhood. He later moved to El Paso, Texas, and occupied a ramshackle house behind a shopping mall on Coffin Street, which reminded him of the coffin in which Queequeg, the Moby Dick harpooner, slept. McCarthy does not do interviews, readings, tours or book signings, but he is not an anti-social recluse like Salinger and Pynchon.

Thrice married, he is an affable sort who dresses like some of the cowboys who inhabit his novels. When asked why he became a writer, he quoted Flannery O’Connor, “Because I do it well.” McCarthy’s idea of a perfect day is to shut himself in a room with a sheaf of blank paper. Determined to make a splash for The Passenger and Stella Maris, his American publisher (Alfred A. Knopf) announced an initial print run of 300,000 copies for each, and 50,000 box sets of both novels.

The biblical undertones of McCarthy’s apocalyptic vision have appeared in every book since his first novel, The Orchard Keeper. When the unsolicited and unheralded manuscript landed on the desk of Albert Erskine, the legendary editor of William Faulkner and Ralph Ellison, he offered McCarthy a contract for five novels. McCarthy followed up The Orchard Keeper (1965) with Outer Dark (1968), Child of God (1973), and the ruthless Suttree (1979), a novel that borders on perfection.

In the early 1980s, McCarthy left Tennessee to settle in the American southwest, where he spent five years learning about the history of the US-Mexico borderlands. A new landscape and reality permeated by the Spanish language added another dimension to McCarthy’s work that was first expressed in Blood Meridian (1985). Based on real events and soaked in bloody violence, Cormac McCarthy’s masterpiece is a metaphysical western that forces us to contemplate the reality of evil and doesn’t let us look away.

McCarthy finally achieved some commercial success in 1992 with All the Pretty Horses, the first volume of his Border Trilogy. His tortured vision of the West, described in a naked prose at once desolate and beautiful, won the National Book Award. The writer declined to attend the award ceremony. His next two novels, The Crossing (1994) and Cities of the Plain (1998) completed the chilling Border Trilogy and featured a mysterious thread of hope that reappeared in later works.

After a seven-year respite, No Country for Old Men was published in 2005. The story is set along the US-Mexico border and graphically portrays the drug-related violence of our time. Commenting on the brutal scenes described in stripped-down prose that lacked almost all punctuation, one critic said that there were more corpses than commas in the book. A picture of pure evil, Anton Chigurh is the main antagonist of the story – a drug dealer, ex-convict, murderer and reincarnation of the indelible Judge Holden of Blood Meridian, himself a direct descendant of Captain Ahab, Melville’s monstrous creation. There is something about McCarthy’s penchant for genre fiction that makes his books compelling film adaptations. In fact, McCarthy wrote No Country for Old Men in six months as a screenplay, and later turned it into a novel. The filmmaking duo of Joel and Ethan Coen wrote and directed the movie, which won four Oscars. All the Pretty Horses and The Road also became successful films.

McCarthy’s two new novels are reminiscent of his best work, full of emotional impact but without the cruelty

Starkly intimate, The Road added some subtle nuances to McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic vision of human existence. The Pulitzer Prize-winning novel tells the story of a man and his son who survive a cataclysmic event that has destroyed civilization. Unlike the extreme pessimism of Blood Meridian, McCarthy’s X-ray of the human soul in The Road is a vanishing point that offers a glimmer of goodness.

McCarthy didn’t publish anything for 16 years after The Road until The Passenger and Stella Maris. While they are being released as two separate novels, they are actually one story about two siblings – Bobby and Alicia Western. Bobby is a salvage diver and Alicia is a math prodigy. Although Bobby’s character is the center of gravity of The Passenger, the plot is driven by Bobby’s relationship with his sister and disturbing themes of suicide and incest. Some of the scenes in The Passenger are reminiscent of David Lynch films that introduce characters and scenes for no apparent reason. At times, the novel evokes some of Thomas Pynchon’s most delirious ramblings. The psychotic projections of Alicia’s troubled mind take on a life of their own and become real characters, an unusual artistic license for McCarthy.

The Passenger is a collection of individual stories that have been deftly woven together into an improbable tapestry. Scientific theories and philosophical speculations of all kinds feature prominently, but in the mouths of The Passenger’s characters, this intellectualism often seems incongruous and threaten to unravel the novel. Nevertheless, Bobby Western’s encounters with a wonderfully complex gallery of characters are reminiscent of his best work, full of emotional impact but without the cruelty. McCarthy’s skillful exposition and gripping dialogue make it impossible to put the book down.

Alicia Western suffers from paranoid schizophrenia and has voluntarily committed herself to the Stella Maris asylum where she commits suicide on the first page of The Passenger. The novel is a transcription of the Alicia’s seven sessions with her psychiatrist at Stella Maris. The in-depth exploration of Alicia’s torments raises every conceivable philosophical topic and a good number of scientific ones, and can often be difficult to follow, trying the reader’s patience. Bobby and Alice’s father was one of the physicists who worked on the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bombs that the United States dropped on Japan to end World War II. It’s difficult to explain, but McCarthy’s maddening yet brilliant novels seem to represent his farewell to the literary and physical worlds.

No comments:

Post a Comment