|

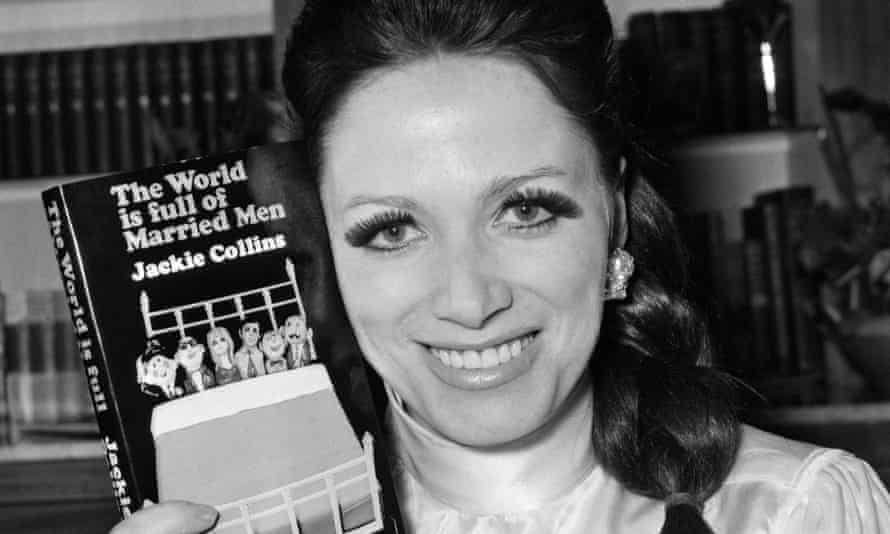

| Jackie Collins in 2013. Photograph: Graham Whitby |

Jackie Collins obituary

Veronica Horwell

Sun 20 Sep 2015 17.50 BST

When the first of Jackie Collins’s novels, The World Is Full of Married Men, was published in 1968, there was a vast gap between the new expectation that women would freely have, and offer, sex and the actual sexual experience and expertise of most young women. To be good at sex they already had to have been bad – in every sense.

Since women had always been greedy readers of fiction and manuals of behaviour, a market opened for books that united both. Jackie’s work was not the first to combine a strong story with how-it-was-done sex – the success of Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls (1966) convinced publisher WH Allen to accept Married Men from an unknown author – but it was original and bold. It was followed by 31 further novels, nearly half a billion copies in total and all on the New York Times bestseller list. For more than 50 years, many interviewers, and most fans, began their conversation by saying Jackie had taught them everything they knew about sex.

Jackie, who has died aged 77, claimed, without going into detail, that she had been a very bad girl, a wild child. She was the daughter of London theatrical agent Joseph Collins and his dancer wife, Elsa, living on the periphery of glamour. Her older sister, Joan Collins, was an actor and performer from the start. Jackie was an observer – she wanted to have, not simulate, experiences and to write about them. She gathered her first material by hiding when small in the trolley of food that her mother wheeled into the Friday night card parties of her father and his friends, listening to what they said about women when they thought none were present.

Joan wanted to be in the spotlight; Jackie wanted to slip out of her bedroom window and go to West End nightclubs. She was expelled at 15 from Francis Holland school, London, for truancy, smoking and mocking the local flasher. Joan married young, disastrously; Jackie followed older lovers, including Marlon Brando, to Las Vegas and the south of France; she visited Joan in Los Angeles. Jackie tried modelling, acting in British B-pictures and television; she sang a little, way down the variety theatre bill.

In 1960, she married a businessman, Wallace Austin, not knowing he was a drug addict who regularly overdosed; after four years together and the birth of their daughter, Tracy, she divorced him, unwilling to wait for the inevitable night the medics didn’t arrive in time after an overdose. He later took his own life. Her second husband, the American Oscar Lerman, flew to Britain to pursue her. He dealt in art and owned nightclubs – London’s Ad Lib, and, later, Tramp – and granted Jackie the access she had always wanted to watch outrageous nocturnal goings-on with no obligation to join in. After the births of their daughters Tiffany and Rory, Jackie spent the day writing, minding the children outside school hours, then stayed up half the night observing the wildest venues of an unrestrained era from their quietest corners.

Jackie had told Lerman she was a writer and so he read the opening pages of Married Men. “Finish this one,” he said – she had abandoned many novels after a few chapters. “You’re a storyteller.” She wrote 10 pages a day hiding out in a seaside resort and soon found a publisher, provoking huge, and profitably adverse, publicity. It was banned in South Africa and Australia, a politician bought an ad in the Sunday People to protest against it as the most disgusting book he had read, and the romantic novelist Barbara Cartland told Jackie she was “responsible for all the perverts in England”. (“Oh, thank you,” Jackie replied, sincerely.)

Today, when millions of women read and many write far more frank erotica online, the reader is less aware of the sex – not evasive, but not that explicit – than of the confidence and independence of its heroine.

Beyond the mechanics of who put what where, heroines – or rather, female heroes – became Jackie’s métier, especially after 1971 when she began to set her work in the US. The Lermans finally settled in Los Angeles in the 1980s. Jackie’s dream country had always been the US, for ethnic variety, social mobility and glamour, and her favourite popular writers, apart from Dickens and Enid Blyton, were American: Mario Puzo, Harold Robbins, Joseph Wambaugh. She admired Puzo’s The Godfather so much that she turned to crime writing in 1974, with Lovehead, and most successfully with her Santangelo family series, nine novels from Chances (1981) to this year’s The Santangelos. She was promoting the title a few days before she died.

The Santangelos share the mafiosi world of the Corleones and the Sopranos, but their women do more than spend, breed and cook, especially Lucky, who inherits and maintains the family firm. “My heroines kick ass,” Jackie said, complaining of contemporary female masochism in print and film. “They don’t get their asses kicked.” Jackie herself was once held up at Uzi-point in her car in Beverly Hills. She reversed out of trouble, fast. “My heroines do what women would – if they had the courage,” she said.

Jackie knew minor mafiosi and got their details right, just as she had, or had met, or had logged well-sourced gossip on several showbiz generations – “I’m a Bel Air anthropologist.”

She was proud that the valets, maids and chauffeurs of Beverly Hills queued to buy copies of her most successful book, Hollywood Wives (1983), in the hope their employers were in it; although she explained that she synthesised rather than copied from life. The women in her version of Hollywood make more, and usually better, choices than they do in the real Tinseltown. Jackie herself produced some films of her books, notably The Stud (1978) and The Bitch (1979), both starring her sister as disco-owner Fontaine Khaled, which helped pull Joan out of a career slump.

Jackie Collins appearing in an episode of the TV series The Saint in 1963.

Lerman died of cancer in 1992, and Jackie’s next love, the businessman Frank Calcagnini, died of a brain tumour in 1998. She worked through it, always paying attention to pop culture and social media to update her writing and to interact with readers, although a TV chat show, Jackie Collins’ Hollywood, flopped. She had had a hard head for business since she sold her rude limericks to schoolmates. She invested in LA property and produced films and TV series based on her books. And she realised that, since her contracts predated digitalisation, she could self-publish her back list profitably as ebooks, and was surprised to find that half her readers in this medium proved to be male.

In 2013 Jackie was appointed OBE for services to fiction and charity. She confided to the Queen that she had been a school drop-out.

Not even Joan knew until the last about the breast cancer from which her sister died. Jackie is survived by Joan, by their brother, Bill, and by her children, Tracy, Tiffany and Rory.

No comments:

Post a Comment