|

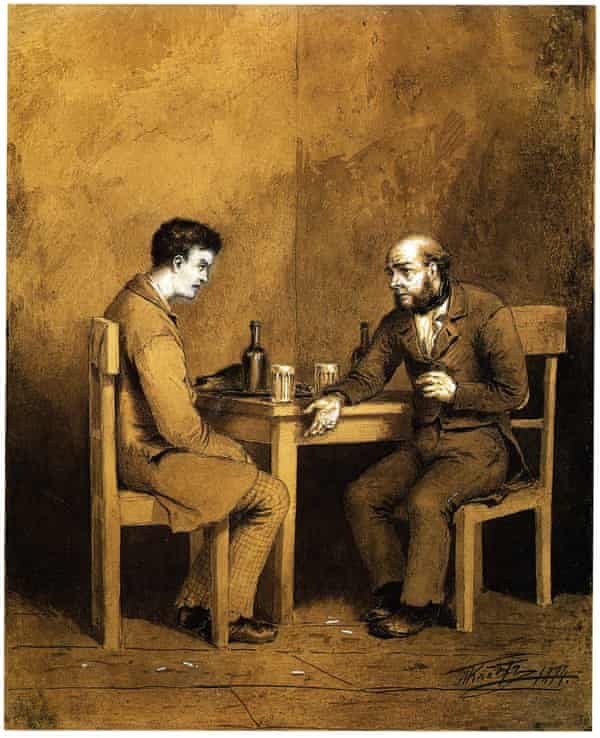

| Dostoevsky |

Dostoevsky in Love by Alex Christofi review – unpredictable, dangerous and thrilling

His marriages were disastrous but his words were so rousing they made strangers embrace ... a superb study of the Russian novelist

Frances Wilson

Thu 14 January 2021

T

When the Isaevas moved to the mining town of Kuznetsk, 700 versts away in southwestern Siberia (a verst is roughly equivalent to a kilometre), Dostoevsky’s love seemed doomed. But then Alexander died, leaving Maria alone and in poverty. Dostoevsky sent her his last roubles and a proposal of marriage, telling the coachman to wait for her answer before making the week-long journey back through the snow. Maria turned his offer down: she could never marry a penniless private. She then fell in love with a man who was just as poor as Dostoevsky, and also a simpleton: “I barely understand how I go on living,” Dostoevsky wrote, aware that this current melodrama was repeating the plot of Poor Folk.

He eventually married Maria, and had his first full epileptic fit on their wedding night. She never recovered from the sight of his writhing, crumpled body: “The black cat has run between us,” as he put it in The Insulted and the Injured. The couple shared not a single day of happiness, but then it is hard to find many days of happiness in his story at all.

The life of Dostoevsky was nothing if not Dostoevskian. It was suffering, he believed, that gave value to existence: “Suffering and pain are always mandatory for broad minds and deep hearts,” he explained in Crime and Punishment. “Truly great people, it seems to me, should feel great sadness on this earth.” His mother, who was also called Maria, had died of TB when he was 15; soon afterwards his father was found dead in a ditch, possibly murdered by the serfs on his estate. Poor Folk made him a literary sensation but earned him no money, and the little money he did earn was lost on the roulette wheel. While his novels mined the psyche, he did battle with his body: myopia, haemorrhoids, bladder infections, emphysema. By the time he was writing Devils, his seizures had become so severe that he had no memory, when he regained consciousness, of either the novel’s plot or the names of his characters.

Dostoevsky, who died aged 56, did not write an autobiography but “buried his heart”, as Alex Christofi, puts it, in his fiction. Christofi, also a novelist, describes Dostoevsky in Love as less a biography than a “reconstructed memoir”. His method, he explains, has been to “cheerfully commit the academic fallacy” of eliding Dostoevsky’s “autobiographical fiction with his fantastical life”. This is achieved by blending his authorial voice with that of Dostoevsky, in sections lifted from the letters, notebooks and fiction and stitched seamlessly into the text. So as not to interrupt the narrative flow, the sources are given only at the back of the book. It’s a witty motif which works well, not least because it immerses us in the forcefield of Dostoevsky’s thought, which Christofi also employs to explain his own waywardness. “Facts,” as Dostoevsky reminds us in Crime and Punishment and Christofi reminds us here, “aren’t everything; knowing how to deal with the facts is at least half the battle.”

One example of how Christofi deals with the facts can be seen in the account of the mock execution with which Dosteovsky in Love begins. Segueing together descriptions from Dostoevsky’s letters with passages from The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov and The Insulted and the Injured, Christofi takes us not only into the moment when Dostoevsky faced the firing squad but also into his novelistic response to that moment: “There was no more than a minute left for me to live,” he writes to his brother. “The most terrible part of the punishment,” he reflects in The Idiot, “is not the bodily pain, but the certain knowledge that in a hour, then in ten minutes, then in half a minute, your soul must quit your body and you will no longer be a man.” The effect is of having Dostoevsky in the room with us, reliving the horror of it all while also being aware of what a good story it makes. What becomes clear is that Dostoevsky the lover was not dissimilar to Dostoevsky the epileptic, Dostoevsky the gambler, or Dostoevsky facing his death: each experience was unpredictable, dangerous and thrilling.

In addition to Maria, Dostoevsky had two further serious love affairs. Polina, the beautiful, unhinged daughter of a serf caused him nothing but grief, while Anna, the stenographer who became his second wife, stood by him while he repeatedly pawned their few belongings and then lost the money at the casino. The way he proposed to Anna, Christofi writes, “is so quietly bashful that you can’t help wanting to hug him”. He is quite right, but I won’t give away the plot.

Christofi’s interest, however, is not only in Dostoevsky as a lover of women. It is also in Dostoevsky as a believer in Christian love. This belief lay at the heart of his novels and by the end of his life he was regarded as a prophet, spreading the gospel of universal harmony. After his famously rousing speech in honour of Pushkin, “strangers sobbed, embraced each other and swore to be better people, to love one another”. Two old men came up to tell him that “for twenty years we’ve been enemies … but we’ve just embraced and made it up. It’s all down to you.”

Novelists tend to make good biographers, not least because they know how to shape a story, and it is no mean feat to boil Dostoevsky’s epic life down to 256 pulse-thumping pages. Dostoevsky in Love is beautifully crafted and realised, but it is the great love that Christofi feels for his subject that makes this such a moving book.

No comments:

Post a Comment