THE LIFEANDLOVES OFANNE LISTER

Kneeling side by side under the medieval arches of the tiny church, two women bowed their heads and prayed.

Candles flickering around them, they took the sacrament at the altar.

But this was not a normal church service; in the lovers’ eyes, their “marriage” had been sealed.

It was 1834. Homosexual acts were illegal and sexual relationships between women were largely unacknowledged - the word lesbian had not even been coined.

But Anne Lister had no truck with the misogynistic conventions of 19th Century England. She was a businesswoman, entered politics and climbed mountains.

And she adored women, falling passionately in love time and again.

The explicit details of her affairs, recorded in code, shocked those who deciphered them.

They changed the way lesbian history was viewed forever.

GENTLEMAN JACK

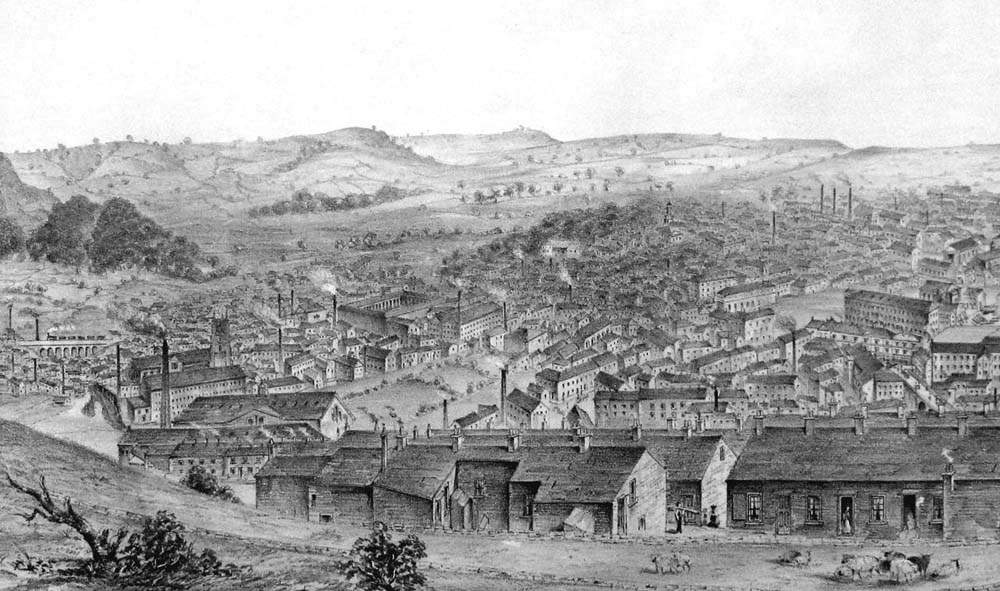

The black-clad figure, striding confidently along the cobbled streets, was a familiar sight in Halifax.

Dressed, even in summer, in thick, black clothes and boots, the young woman’s boyish frame drew whispers and abuse.

“That’s a man!” one voice jeered, a taunt she had become used to.

Anne Lister, with a little hat - also black - sitting atop her tight, black ringlets, marched on, seemingly unperturbed.

The peculiarly dressed, haughty woman from the nearby manor house Shibden Hall stood out in the working-class Yorkshire town.

Educated and confident, in an age when women were rarely either, she attracted attention wherever she went.

“The people generally remark, as I pass along, how much I am like a man,” she confided in her diary, the writing of which was a daily ritual.

Men would often jokingly proposition her as she walked by. Others sent her anonymous, mocking and abusive letters. A practical joker had an advert placed in the Leeds Mercury in her name, looking for a husband.

They also gave her a cruel nickname - Gentleman Jack.

Since childhood she had been different. Born in 1791, Anne was an “unmanageable tomboy” whose exasperated mother sent her off to boarding school aged seven.

Teachers feared she would influence the other girls with her rebellious behaviour and in her teens, she was confined to an attic bedroom, where she lived in virtual seclusion.

Her diary became her closest confidante. Feeling alone in a world she didn’t quite fit into, she poured her deepest thoughts on to the pages of her journals.

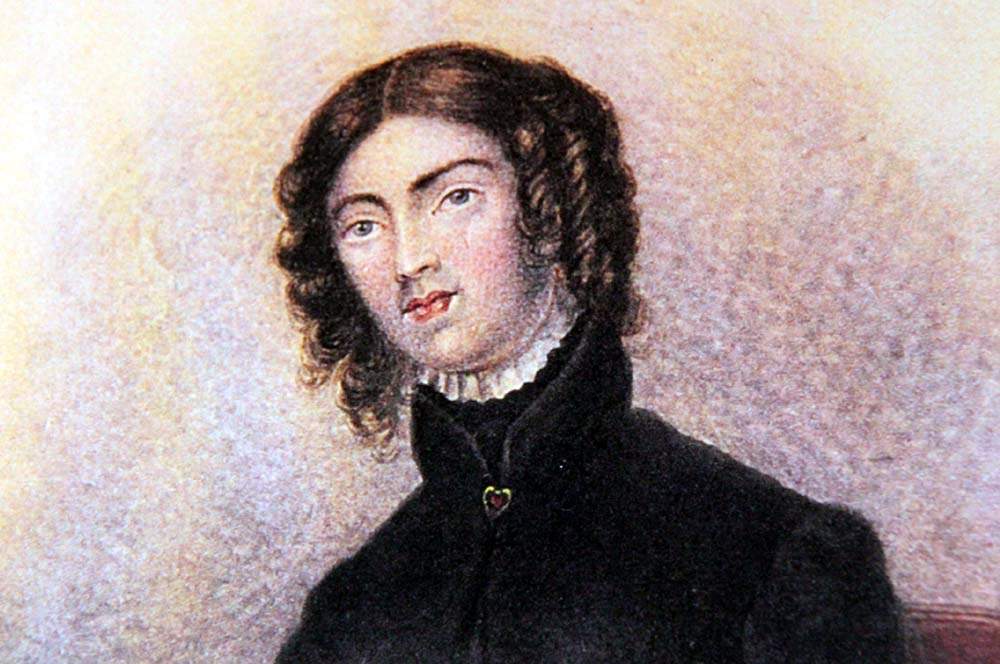

There are few pictures of Anne, but this one shows her in her youth

So obsessive was her personality, no detail was left out: the time she woke up and how long she’d slept; the letters she received and their contents; the day’s weather; the time it took to walk into town; whether she’d enjoyed veal cutlets or mutton for dinner.

Everything she had learned that day would be recorded too: Greek, algebra, French, mathematics, geology, astronomy and philosophy. Anne possessed a voracious intelligence and - at a time when women were barred from universities - was determined to learn everything a man was able to.

But there was something else that Anne spilled on to the pages of her diary: she adored women.

Her first sexual experience was with a fellow pupil, Eliza Raine, who was sent to live with her in the school’s attic.

The illegitimate half-Indian daughter of an English surgeon, Eliza was another outcast. Thrown together, the 15-year-olds had embarked on a passionate affair right under their teachers’ noses.

In their diaries, both girls would write “felix” - meaning happy in Latin - to record their sexual encounters. But Anne wanted to record more detail. She devised a code from Greek and Latin, mathematical symbols, punctuation and the zodiac to disguise her innermost thoughts.

It was, she believed, completely indecipherable.

Anne was not allowed to sleep in the dormitory at Manor House School, York

While Anne was a passionate lover there was a calculating and ruthless side to her. She dreamed of being rich and Eliza was set to inherit a substantial sum. Money would allow Anne to enjoy the high society lifestyle she craved without marrying a man.

So while Eliza was bowled over by Anne’s affection and attention, Anne’s intentions were more businesslike.

As Anne became more confident about her sexuality - her “oddity” as she described it - she decided she wanted more women, too. She rejected Eliza, sending her former lover into a deep depression.

“You can little know what pain you have given me,” wrote the heartbroken young woman, distraught at Anne’s change of heart. Indeed, she never recovered, eventually being committed to a lunatic asylum.

Anne, while regretful, had a new obsession - the beguiling daughter of a local doctor. She would be the love of Anne’s life, holding her in her grip for almost 20 years, breaking her heart time and time again.

MARIANA

On the surface, Anne was a respectable and quick-witted young woman who spent much of her time in self-imposed study.

Away from her books, she enjoyed walks across the Pennines and leisurely, tea-filled soirées with her well-heeled friends.

While these appeared innocent enough they were the ideal cover for Anne, who used them to explore her increasingly insatiable sexual appetite.

Anne’s “oddity” intrigued her; she trawled books on anatomy to comprehend where her feelings came from, to no avail. But as she came to terms with her sexuality, there was no self-loathing. Her feelings were entirely natural, she believed: her God-given right.

Women, while usually confused about their feelings for Anne, were typically captivated by her. Anne was promiscuous and arguably predatory, moving efficiently from one lover to the next, without them penetrating her heart.

The “sweet-looking” Mariana Belcombe was different, however.

With Mariana, Anne fell dizzyingly in love. The 21-year-old doctor’s daughter was part of the genteel York society Anne had charmed her way into.

For years, they would travel 40-odd miles by horse and cart between York and Halifax to see each other. When apart, they would write to each other every few days. The young lovers even exchanged rings as a symbol of their commitment.

Of course, all of this took place beneath the surface.

Romantic friendships between unmarried women were not unusual. Parents, fearful of pregnancy, would encourage young women to form close relationships with one another before ultimately getting married.

Anne was totally uninterested in society’s expectations, however. She wanted everything a man could have - and that included a wife. Despite the scandal it would have created, she began to harbour hopes she and Mariana would set up home together.

But in 1815, Mariana made a dramatic announcement: she had agreed to marry a wealthy widower. Anne watched the wedding, anguished, from the pews of a York church. But there was more to come.

It was customary for female friends to accompany the bride and groom on their honeymoon, and it was Anne, along with one of Mariana’s sisters, who endured the excruciating experience.

On her return to Shibden, she spilled her rage on to the pages of her journals, accusing her former lover of “legal prostitution”.

“She believed herself, or seemed to believe herself, over head and ears in love,” she wrote. “Yet she sold her person to another.”

Anne resumed her affairs with Yorkshire’s eligible women, Mariana’s older sister Anne among them. But she confided in her diaries the pain caused by Mariana.

“Surely no-one ever doted on another as I did then on her,” she wrote.

Then, after a year apart, Anne and Mariana met again at her parents’ house in York. Neither could wait to be reconnected. Mariana was in bed with toothache and sneaked Anne into her bedroom.

“She herself suggested a kiss,” Anne later wrote. “I thought it dangerous and would have declined but she persisted.”

Their affair had been reignited. Over the ensuing years it would continue through clandestine meetings and dozens of emotionally charged letters.

Anne preoccupied herself with other women while Mariana was holed up in her Cheshire mansion. But when they were reunited, her lover implored her to be loyal.

“Sat up lovemaking,” Anne wrote one evening after a night spent with Mariana. “She [asked me to swear] to be faithful, to consider myself as married.

“I shall now begin to think and act [as] if she were my wife.”

Anne’s hopes were to be dashed again.

It was August 1823 and Mariana was travelling by stagecoach from Cheshire to visit Anne at Shibden.

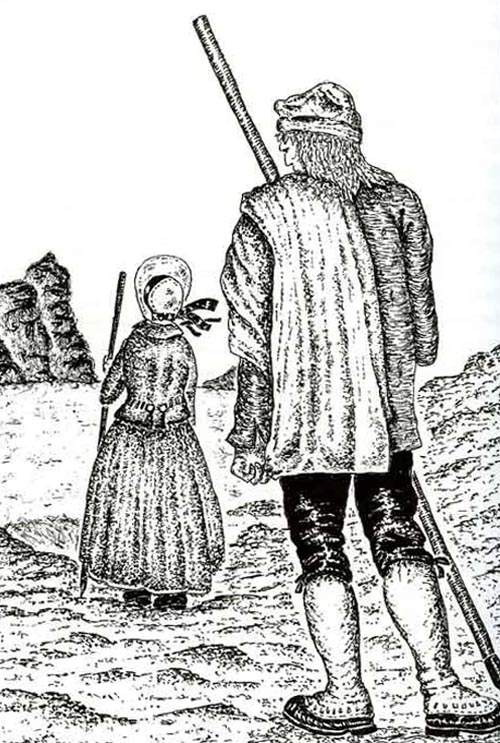

Gripped by an almost maniacal excitement, Anne decided to surprise her lover by meeting her en route. Armed with water and biscuits, she left the manor house and walked 10 miles in the pouring rain over the moors.

After several hours, she reached the wilds of Blackstone Edge, a gritstone cliff. There she saw her lover’s carriage trundling up the hill. Bedraggled, she leapt in, and clambered over the boxes before landing next to a sleeping Mariana.

Anne met the carriage on the wilds of Blackstone Edge

Mariana awoke, shocked by Anne’s bizarre and impulsive act. In the carriage were her sister, a passenger and his maid. Fearing the incident would fuel gossip and rumour, she was furious.

Their relationship was never the same again.

Some weeks later, as they lay in bed, Mariana told Anne she was ashamed to be seen in public with such a masculine-looking woman. As tears rolled down Anne’s cheeks, Mariana did nothing to comfort her.

Anne was heartbroken.

“Oh, women, women!” she wrote. “I am always taken up with some girl or other. When shall I amend?”

THE CODE

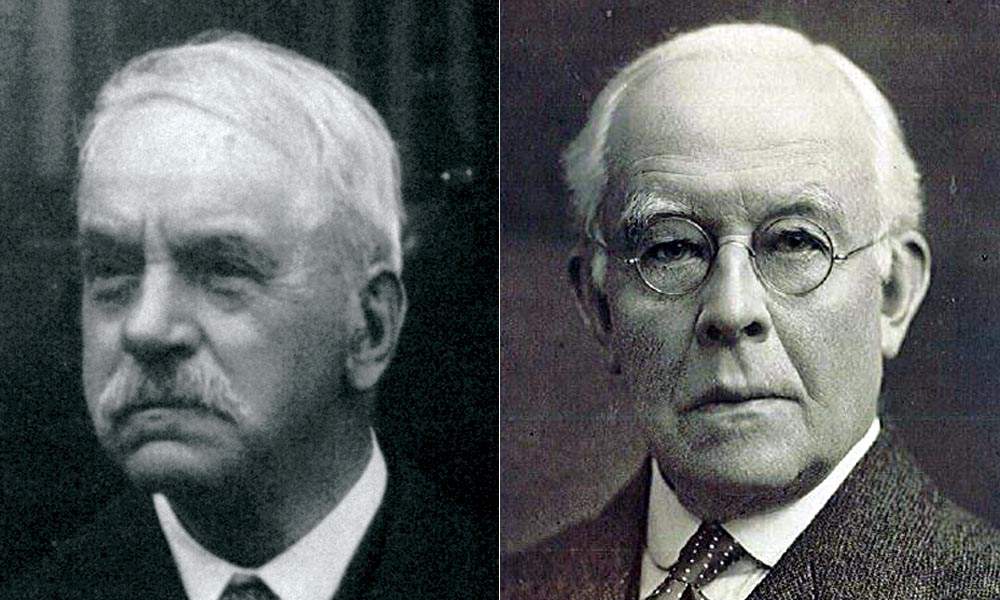

Seven decades later in the 1890s, reading by candlelight inside one of Shibden’s many dark, oak-paneled rooms, John Lister stared at the rows of unintelligible squiggles spread across the leather-bound book before him.

The key to the strange code that littered his ancestor Anne Lister’s journals had evaded him for years. Tonight he was resolved to crack it.

He had enlisted the help of a friend, schoolteacher Arthur Burrell. After borrowing some of the diaries he was confident he had worked out two coded letters - h and e.

A tiny bit of paper, scribbled on by Anne and found hidden behind the manor house’s deeds, confirmed his suspicions.

“In God is my…”, it began, the final four-letter word in code.

“We saw at once the word must be ‘hope’; and the h and e corresponded with my guess,” Arthur later recalled. “With these four letters almost certain, we began very late at night to find the remaining clues.”

A few hours later, the shocked men learned what Anne Lister had been hiding from the world - her detailed and plentiful accounts of sex with her friends.

“Hardly any one of them escaped her,” an appalled Arthur later recalled.

He implored his friend to burn the diaries to avoid bringing scandal on the proud Lister name. But while dismayed at the contents, which would humiliate his family if published, John could not bring himself to destroy them.

Instead he hid all 26 volumes on shelves concealed behind Shibden’s wood panelling, where they remained until his death in 1933.

Shibden’s network of dark rooms hid Anne's secret for decades

In the following years, with the hall now in public ownership, Anne’s diaries were discovered and gifted to Halifax Library. A reluctant Arthur Burrell, by then in his 80s, decided he was honour-bound to give the council details of the code.

“My copy of the clue will be burnt later,” he told them.

In the decades that followed, a small number of researchers studied Anne’s letters and journals. However, a council committee demanded to see their work first to remove any “unsuitable material”.

The academics acquiesced to the cover-up, leaving the secret hidden.

In a room in Halifax Library, the hefty microfilm machine whirred into action. It was 1982 and Helena Whitbread, a 52-year-old teacher, was staring at line after line of tiny, unfathomable symbols flashing before her.

Helena, who had recently completed a history degree, had been looking for a subject for a book and was intrigued by Anne’s story.

As she gazed at the microfilm she noticed the code sometimes filled entire pages. On other occasions it would be interspersed with sentences in English.

“I was hooked,” she says. “What was she hiding?”

A library worker gave her a photocopy of Arthur’s code. This time, no-one requested to scrutinise what Helena might discover. She took home Anne’s 1817 diary to begin unraveling the mystery.

Modern understanding of lesbian history - and the next four decades of Helena’s life - would be shaped by what she discovered.

The work was painstaking. In 34 years, Anne had written an exhausting five million words in 26 volumes, with a further 14 travel diaries on top of that. About a sixth of this was written in cipher.

At first there were only subtle clues to the nature of Anne’s secret. In a coded passage in 1817 Anne confided she was wearing “gentleman’s braces” to hold up her drawers.

Other hidden sentences were about money issues. Mariana’s name began to appear in code, and while it was obvious the women had a deep friendship, the true nature of their relationship was unclear.It was when Helena deciphered the passage of 12 December 1817, when Anne was in York to see Mariana for the first time since her honeymoon and had crept into her room, that her secret was revealed.

“I took off my pelisse and drawers, got into bed and had a very good kiss, she showing all due inclination and in less than seven minutes, the door was unbolted and we were all right again,” Anne had written.

Helena Whitbread pored over Anne’s diaries for years

Helena realised that “kiss” was in fact code for sex, while a Q with a curl denoted a sexual experience.

She deduced that “incurred a cross” was a reference to Anne’s orgasms, which were frequently marked in the margins with an X. The depth of Anne’s relationship with Mariana had become clear.

Anne also often referred in detail to “grubbling”- or groping - a word that appeared time and again.

“Of all the things I thought she was hiding, it wasn’t sex with other women,” says Helena. “I think the feeling was... ‘Oh my God - here is an absolutely truthful - I’m sure it was truthful - account of lesbian sex’.”

After five years spent poring over diaries written between 1817 to 1824, Helena published a book detailing the fraught relationship with Mariana and Anne’s tangled web of lovers across Yorkshire.

When I Know My Own Heart was published in 1988 it caused a sensation.

Until then, clear evidence of sex between women had been absent from the historical record. Anne’s journals detailed a lesbian lifestyle many thought had not existed in the past.

Her promiscuity showed not only that women found her attractive but that sexual lesbian desire had been far more commonplace than was thought. Anne’s diaries and their explicit sexual details were so shocking that some even believed they were a hoax.

It was no exaggeration when the writer and historian Emma Donoghue described the Lister diaries as “the Dead Sea Scrolls” of lesbian history.

John Lister, left, and Arthur Burrell cracked the code

“Anne leaves us this voluminous record that’s quite difficult to work with but tells us so much about lesbian life in the 1800s,” says Dr Caroline Gonda, of Cambridge University.

“She tells us about relationships that don’t fit the idea of ‘romantic friendship’ in the 1800s - it’s not all chaste hand-holding, pressing flowers and braiding each other’s hair.

“It’s so important that she goes into so much detail about her sex life. Women’s sexuality has always either defined us entirely or been thought to be completely absent.”

But what is also crucial about Anne’s story is that she was not alone.

“People say she was a one-off but there’s a community there,” says Dr Gonda. “She’s not the only gay in the village.

“Although Anne is a bit of a bad lass, a bedpost notcher, and a terrible snob, she tells us so much about sexual desire in lesbian history.”

ICARUS

Music filled the Parisian air as Anne Lister strolled down the Champs-Élysées, gazing at the cheerful crowds gathered under its famous horse chestnut trees.

She felt at home in the French capital, having fled there to escape Yorkshire and the shadow of Mariana.

The relaxed atmosphere emboldened her to be more open with her sexuality, and she wasted no time in propositioning the other visitors at the guesthouse in 24 Place Vendome.

When a Frenchwoman innocently kissed her goodbye on both cheeks, demonstrating the European custom, Anne pressed her lips straight on to hers.

“That is Yorkshire,” she told her, proudly.

Paris in 1824 was the perfect playground for Anne. She intended to learn the language, immerse herself in the culture and, hopefully, meet a sophisticated, wealthy woman.

While Maria Barlow, a widow from Guernsey, wasn’t exactly the titled demoiselle she had envisaged, she fell for her “ladylike and pretty” new friend regardless.

Anne’s coded diaries described her sexual liaisons in more detail than before.

Anne stayed in a guesthouse at 24 Place Vendome

“I had kissed and pressed Mrs Barlow on my knee till I had a complete fit of passion,” one of her more modest passages read. “My knees and thighs shook, my breathing and everything told her what was the matter.”

She went on: “Then made several gentle efforts to put my hand up her petticoats which, however, she prevented.

“But she so crossed her legs & leaned against me that I put my hand over & grubbled her on the outside of her petticoats till she was evidently a little excited.”

The women enjoyed a fiery affair before Anne grew weary of Maria’s moods. She left her crying lover, returning to Yorkshire without a backward glance.

Anne’s eight-month stay in Paris, had, however, ignited a passion for travel.

Anne described the view from Monte Perdido as “the perfect solitude”

Exhilarated by her “wild but delightful wanderings” she would go on to explore more than a dozen countries over the next 15 years.

Even the death of her beloved uncle James, which led her to inherit her faded ancestral home of Shibden, failed to keep her rooted.

Anne had little care for Halifax. Her diaries reveal her snooty, snobbish attitude towards its people and her certainty she was destined for better things.The added income from Shibden helped fund her travels.

Her tours took in most of the major cities of Europe. She would typically be accompanied by her female friends, including Mariana, with whom she intermittently continued to have sex.

But she also set her sights on more extreme locations. She travelled to the Pyrenees, intent on climbing the icy peaks in her long black skirt and petticoats.

Writer Marta Iturralde drew a sketch of Anne’s ascent

Here she enlisted a smuggler as a guide and, with crampons secured to her feet, an iron stick and a map in her hands, she ascended the steep, icy terrain of the Breche de Roland.

The next day she conquered Monte Perdido, the third highest peak in the range.

“The view was magnificent, particularly towards Spain,” Anne later wrote. It was, she said “the perfect solitude. The profound stillness that gave me a sensation I had never had before”.

Anne’s travels satisfied an ambition she had held since childhood; to see with her own eyes the places she had read about.

As she entered her late 30s, Anne also moved tantalisingly closer to fulfilling another dream. She had always felt high society was her natural home, a sophisticated world made for someone of her quick wit, learning and social status.

But although the Listers were minor gentry, her branch was relatively poor. Inheriting Shibden gave her the means to support a more luxurious lifestyle. An old friend from her time on York’s social scene introduced her to a group of aristocratic women. Invitations to elegant events soon began to arrive.

Anne stood among the crowds as Charles X received the keys of Paris

She travelled to Paris with the alluring Vere Hobart, sister of the 5th Earl of Buckinghamshire. Anne was fascinated by her young, stylish friend - but so were men.

As the women rubbed shoulders with 2,000 important guests at a British Embassy event, Anne watched jealously as Vere danced with the son of the future king Louis Phillipe.

The women were very close, however. When Vere proposed the friends take an extended trip to the southern English coastal town of Hastings, Anne jumped to accept.

Over the next five months they enjoyed the resort’s social scene and Anne, perhaps deluding herself, began to believe she might have found the woman who would fulfil her romantic dreams.

Vere had the looks, breeding and wealth Anne had thirsted over for years. But society and its expectations once again prevailed. Anne lost out in familiar fashion: Vere agreed to marry an army officer. Heartbroken and embarrassed, Anne cried for days.

Her money was also running out.

“My high society plans fail,” she told her diary. “I have had my whim - tried the thing - & pretty much it has cost me.”

She resolved to go back to Halifax and Shibden and - for the first time in years - stay there.

“I have been an Icarus – but shall fall less fatally, for I can still live and be happy,” she wrote. “Here I am at forty-one, with a heart to seek. What will be the end of it?”SHIBDEN

Shibden Hall had belonged to the Lister family for more than 200 years. A medieval manor house tucked behind a hill, its black and white facade hid a network of dark rooms within.

Anne channeled her anger at her latest rejection into reviving her ancestral home. She thought Shibden shabby and cold - after spending much of the past decade in a succession of elegant resorts she now coveted a grander home and beautifully manicured gardens.

She also revolutionised the estate’s finances. Halifax’s recent industrial boom had produced a huge demand for coal. Anne spotted the opportunity and quickly expanded Shibden’s collieries.

Her determination to be hands-on marked her out from other women with property. She took on the men who ran the local coal industry and they soon learned she possessed a shrewd business brain.

Anne told her diary how a coal merchant she had driven a hard bargain with complained “he was never beaten but by ladies and I had beaten him”.

For all its perceived faults, Anne felt most at home at Shibden, remarking, “I have been happier here than anywhere else.”

There was not a corner of the estate she did not have forensic knowledge of and her diary was full of the minutiae of estate business.

Amid the horticulture and landscaping references, though, a new name began to appear on the pages.

Ann Walker was a shy, gentle 29-year-old heiress from a larger neighbouring estate.

The two women had first met years ago, when Anne was in her 20s and Ann just a teenager.

Fifteen years later, the demure Miss Walker made a much bigger impression on her neighbour.

Within a week of being reacquainted, Anne was imagining the two of them together. As with her previous prospective lovers, the young heiress’s fortune was part of the attraction. Anne hoped their combined wealth would enable her to complete her ambitions for Shibden, leaving enough spare to keep travelling.

“She little dreams what is in my mind,” she wrote that night. “She has money and this might make up for rank. We get on very well so far.”

Anne’s infatuation with her new friend accelerated quickly.

“Incurred a cross thinking of Miss W - first time,” Anne confided in her journal, recording the first of many orgasms her new acquaintance would induce.

They began spending time in a secluded cottage in the grounds of Shibden that Anne had built for her own privacy and called the moss house. Within weeks of their meeting again, their relationship became intimate. Ann responded warmly - and enthusiastically - to Anne’s sexual advances.

“I really did feel rather in love with her in the hut,” Anne told her journal. “Perhaps after all, she will make me really happier than any of my former flames.”

The wealthy Walker family lived at Crow Nest in Lightcliffe

Throughout her relationships, Anne had seemingly been on a collision course with the society she inhabited. She sought a woman to live with openly when such arrangements apparently had no precedent.

Mariana and Vere had both decided to marry men, but these decisions were as much to do with meeting society’s expectations as they were a rejection of Anne. But while many women bowed to the inevitable, Anne consistently refused to conform.

After just two months, she made her intentions clear to her young lover. She wanted them to live together at Shibden, like a married couple, and share their wealth and property. But Ann was fraught with anxiety.

Confused about her closeness to another woman and still grieving over the deaths of her fiancé and parents, she asked for six months to deliberate her decision.

When the judgement day arrived, she sent Anne a letter. It read: “I find it impossible to make up my mind”.

CAPTAIN LISTER

Anne Lister’s “wedding” to Ann Walker took place at Holy Trinity church in York on Easter Sunday 1834.

The event was purely symbolic - attending church with another woman and taking communion was ceremony enough for Anne. She took the values of a traditional union seriously. Her promiscuous days were over.

Mariana, who had continued to be part of Anne's life throughout all her foreign flings and high society schemes, admitted defeat.

“Dearest Fred,” she wrote in a letter, using her pet name for Anne. “The die is cast and Mary [ie Mariana] must abide by the throw. You at least will be happy.”

The “newlyweds” embarked on a honeymoon - three months of travel through France and Switzerland. On their return, Anne installed her new “wife” in Shibden. Carts laden with furniture rumbled up the track between their homes.

The scandal was soon the talk of Yorkshire. Anne Lister, who had been mocked for looking like a man for so many years, was now very much acting like one.

The cohabitation of two prominent women was outrageous, but without the language or the understanding to describe their relationship, critics opted for pranks instead.

A mocking advert appeared in the Leeds Mercury announcing the marriage of “Captain Tom Lister of Shibden Hall to Miss Ann Walker”. Anonymous letters also arrived addressed to “Captain Lister” congratulating the couple “on their happy connection”.

“Probably meant to annoy, but, if so, a failure,” Anne told her journal, her anger bristling under the surface.

CAPTAIN LISTER

Anne Lister’s “wedding” to Ann Walker took place at Holy Trinity church in York on Easter Sunday 1834.

The event was purely symbolic - attending church with another woman and taking communion was ceremony enough for Anne. She took the values of a traditional union seriously. Her promiscuous days were over.

Mariana, who had continued to be part of Anne's life throughout all her foreign flings and high society schemes, admitted defeat.

“Dearest Fred,” she wrote in a letter, using her pet name for Anne. “The die is cast and Mary [ie Mariana] must abide by the throw. You at least will be happy.”

The “newlyweds” embarked on a honeymoon - three months of travel through France and Switzerland. On their return, Anne installed her new “wife” in Shibden. Carts laden with furniture rumbled up the track between their homes.

The scandal was soon the talk of Yorkshire. Anne Lister, who had been mocked for looking like a man for so many years, was now very much acting like one.

The cohabitation of two prominent women was outrageous, but without the language or the understanding to describe their relationship, critics opted for pranks instead.

A mocking advert appeared in the Leeds Mercury announcing the marriage of “Captain Tom Lister of Shibden Hall to Miss Ann Walker”. Anonymous letters also arrived addressed to “Captain Lister” congratulating the couple “on their happy connection”.

“Probably meant to annoy, but, if so, a failure,” Anne told her journal, her anger bristling under the surface.

The marriage was not plain sailing. The women were completely different characters - Anne assertively ruled her estate and became embroiled in local politics while her new wife often felt neglected, suffering regular bouts of sadness.

Shibden Hall, mid-renovation, resembled a building site. Ann, whose wealth was largely funding the work, became increasingly “hysterical” about the cost. Nevertheless she stumped up more cash for repairs.

In 1838, Anne wanted to go abroad again. They headed to France via Brussels, but Ann was not the ambitious travelling companion Anne had hoped for. She made frequent complaints of illness that Anne suspected were concocted.

Returning to the Pyrenees, Anne decided she wanted to be the first person to officially climb Vignemale, the highest mountain in the range. Her wife, unsurprisingly, refused to join her.

Undeterred, Anne tied her dress and petticoats around her legs and - wearing nail-studded leather boots - made her way up the mountainside.

A Russian prince wrongly claimed to have beaten her to the summit, to Anne’s anger. He later had the ascent named after him. But a nearby mountain pass is known as Collado de Lady Lister to this day.

Anne tied her dress around her legs and conquered Vignemale

It was to Russia that the couple travelled next, fulfilling Anne’s long-held dream. They explored St Petersburg, and then headed to Moscow, described by Anne as “the most picturesquely beautiful town I have ever seen”.

As the bitterly cold Russian winter arrived, Ann pleaded to go home. But Anne convinced her to stay. She bought them a new carriage, had two pairs of men’s knee-length leather boots made and fur coats, and on they travelled.

Their destination was the Caucasus, a hot and humid mountainous region between the Black and Caspian seas. In the summer of 1840 they reached the city of Kutaisi.

The women marvelled at the lush forests and azalea-clad mountains. The couple also seemed to be enjoying a happy spell, as they shared in the joy of witnessing sights most westerners had never experienced.

In the remote village of Jgali, Anne described the views in her journal.

“High hills north, and, within, ridges of wooded hill rising every now and then into little wooded conical summits.” They’d had tea at 8.25pm and lay down at 9.30pm, she noted.

The simple observations would be the last thing Anne Lister would ever write. It was 11 August 1840.

Six weeks later, Anne, aged 49, was dead

DISSECTED

It is thought an insect bite led to the fever that killed Anne.

Ann Walker was stranded 4,500 miles from home. It took her eight, long, unbearable months to bring Anne’s body back to Halifax, travelling through northern Europe with her coffin beside her.

As decreed in her partner’s will, Ann inherited the Shibden estate. She continued living at the hall, which now boasted the improvements Anne had ordered but never got to see.

Her ownership did not last long, however.

Her relatives, believing she had mental health problems, arranged for a doctor, lawyer and policeman to break in.

Ann was found cowering behind a locked door surrounded by papers and a brace of loaded pistols. She was taken off to the same York asylum that still housed Eliza Raine.

Ann Walker barricaded herself inside Shibden’s so-called Red Room

The survival of Anne Lister’s diaries is partly down to Ann, who ensured the final volumes made it back safely from the Caucasus.

But it would be almost 150 years before their contents would be revealed. They have just been painstakingly restored by a team of experts at the West Yorkshire Archives Service.

A rainbow plaque erected in her memory at Holy Trinity Church, York - scene of her marriage to Ann Walker - now describes Anne as the “first modern lesbian”.

While this definition is debated, Anne’s importance to lesbian history is not in dispute. Her diaries stand alone.When the Queer British Art exhibition was held at Tate Britain in 2017, its curator Clare Barlow described the history of queer culture as being “punctuated by dustbins and bonfires”.

Similar records of female homosexuality are thought to have been destroyed by shame-filled families – just as Arthur Burrell suggested.

That John Lister chose to preserve Anne’s diaries is therefore remarkable. It is not known whether he did so out of a love of history or whether, as has been suggested, he was also secretly homosexual.

A new BBC One and HBO drama Gentleman Jack, starring Suranne Jones as the indomitable Anne, tells her story from 1832, when she started transforming Shibden and her relationship with Ann Walker began to flourish.

Suranne Jones, left, said playing Anne Lister was an “uplifting” experience

Its transmission is the culmination of a 20-year dream of television writer Sally Wainwright, who grew up just a few miles from Shibden Hall.

Overawed by Anne’s “phenomenal intelligence” and fascinating, conflicted personality - “very down to earth but mercurial” - Sally first pitched an idea for an Anne Lister drama in 2003 but was knocked back.

She believes changing attitudes to sexuality are enabling Anne’s story to be told now. “She’s been hidden away, people didn’t want to show off about her,” she says.

Anne’s insatiable appetite for life and almost neurotic documentation of her every move means there are many aspects of her personality to explore.

She was a woman of great intellect and scientific knowledge; during a private lesson in Paris, for instance, she dissected a woman’s head for fun. Her penchant for keeping clippings of her lovers’ pubic hair is another aspect of her intriguing personality.

But while eccentric, she certainly wasn’t always likeable.

The Lister diaries have been restored by experts

“Anne Lister was amazingly deft at controlling situations and manipulating people to further her considerable ambitions,” says Jill Liddington, whose book Female Fortune inspired the Gentleman Jack series.

“She certainly took advantage of lonely Ann Walker’s wealth, but in seducing her, she behaved no more caddishly than any other suitor whose expenditure ambitions exceeded his income.”

Living in a lesbian marriage in the 1830s, albeit discreetly, demonstrated “extraordinary bravado”, Jill added.

This determination to live life on her own terms continues to inspire those who discover Anne’s story.

Suranne Jones says she found the experience of playing Anne “uplifting” - and was even inspired to keep a diary.

“It’s a lesson in our age about being authentic,” she says of Anne’s attitude. “About having a voice and using it - standing up for yourself.

“There was no blueprint for what she was doing, she was just being herself. As you’re playing her, you just become aware that you have a right to be a person, you have a right to be who you are.”

Helena Whitbread, who revealed the contents of the Lister diaries, said Anne had earned her place in history. She praised her “outstanding courage, fearless enough to approach life on her own terms and fashion it to her liking, according to the nature which, as she saw it, God had endowed her”.

It’s a sentiment Sally Wainwright agrees with.

Because the language of the 19th Century didn’t encompass lesbianism “nobody could actually call her out on it, and if they’d got anywhere close to it Anne would have just run rings around them,” she said.

“She had a really healthy sense of her own self worth. She can teach us all a thing or two.”

La fascinante vida de Anne Lister, la "primera lesbiana moderna"

DRAGON

My hero / Anne Lister by Emma Donoghue

The life and loves of Shibden Hall's Anne Lister

Anne Lister / The First Modern Lesbian

The Life and Loves of Anne Lister

No comments:

Post a Comment