Forgotten Authors

No 5

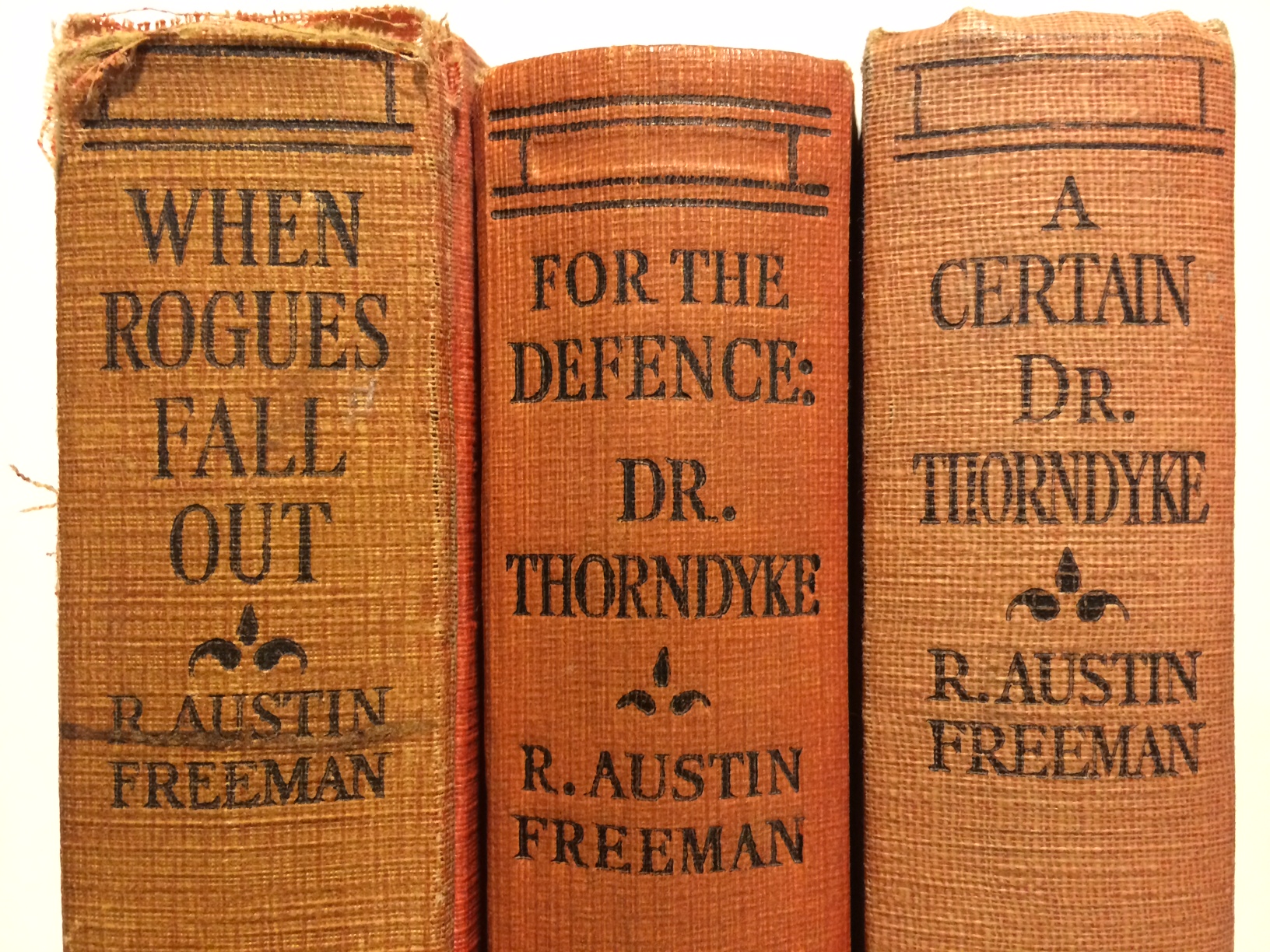

R. Austin Freeman

“Freeman … treats criminals in a more balanced manner than Conan Doyle. His working-class characters – particularly in Mr Polton Explains – are decent, skilled and hard-working, but are still crushed by the system. His 30-odd books are certainly worth rediscovery.”

Richard Austin Freeman enjoyed a prolific career that saw him gain qualification as pharmacist and surgeon, pull off a diplomatic coup along the Gold Coast, work for Holloway Prison and become a formidable man of fiction. For the first twenty-five years of his writing career, Freeman was to dominate and remain unrivalled in the world of detective fiction, introducing the well-loved and highly memorable Dr Thorndyke. Through the creation of this character, Richard Austin Freeman continues to be read as an extremely popular addition to the world of the mystery novel.

Dr. Richard Austin Freeman MRCS LSA (11 April 1862 – 28 September 1943) was a British writer of detective stories, mostly featuring the medico-legal forensic investigator Dr. Thorndyke. He invented the inverted detective story (a crime fiction in which the commission of the crime is described at the beginning, usually including the identity of the perpetrator, with the story then describing the detective's attempt to solve the mystery). Roberts said that this invention was Freeman's most noticeable contribution to detective fiction. Freeman used some of his early experiences as a colonial surgeon in his novels. Many of the Dr. Thorndyke stories involve genuine, but sometimes arcane, points of scientific knowledge, from areas such as tropical medicine, metallurgy and toxicology.

Austin Freeman was the youngest of the five children of tailor Richard Freeman and Ann Maria Dunn. At the age of 18 he entered the medical school of the Middlesex Hospital and qualified MRCS and LSA in 1886.

After qualifying, Freeman spent a year as a house physician at the hospital. He married his childhood sweetheart Annie Elizabeth Edwards in London on 15 April 1887,[4] and the couple later had two sons. He then entered the Colonial Service in 1887 as an assistant surgeon. He served for a time in Keta, Ghana, in 1887 during which time he dealt with an epidemic of black water fever which killed forty percent of the European population at that port. He had six months of leave from mid 1888 and returned to Accra on the Gold Coast just in time to volunteer for the post of medical officer on the planned expedition to Ashanti and Jaman.

Freeman was the doctor, naturalist and surveyor for an expedition to Ashanti and Jaman, two independent states in the Gold Coast. The expedition set out from Accra on 8 December 1888, with a band consisting of a band-master and six boys playing two side drums and five fifes,[7] three European officers (Freeman, the Commissioner, and the Officer in Charge of the Constables), one Native officer, 100 Hausa constables, a gunners' party with a rocket trough, an apothecary, apothecary's assistant, a hospital orderly, and 200 bearers. The expedition went first to Kumasi (or Coolmassie as it appears in older accounts), the capital of the then independent kingdom of Ashanti. Their second port of call was Bondoukou, Ivory Coast, where they arrived only to find that the king had just signed a protectorate treaty with the French.

However, the expedition was a political failure as the British spokesman blurted out in front of the chiefs the British were willing to supply the loan of £400 which the king had requested. However the King had requested this loan with the proviso that it be kept secret from his chiefs. He therefore denied any knowledge of the loan and the expedition moved on to Bontúku, the capital of Jaman. Here they were left cooling their heels while the King there finalised a treaty with the French, who had been quicker off the mark. The expedition was recalled after five months.[9] Bleiler asserts, without any supporting evidence, that It was mostly through Freeman's intelligence and tact that the expedition was not massacred. Although the mission overall was a failure, the collection of data by Freeman was a success, and his future in the colonial service seemed assured. Unfortunately, he became ill with blackwater fever and was invalided home in 1891, being discharged from the service two months before the minimum qualification period for a pension.

Career

Thus, he returned to London in 1891, and in c. 1892 served as temporary Acting Surgeon in Charge of the Throat and Ear Department at Middlesex Hospital. He was in general practice in London for about five years. He was appointed acting Deputy Medical Officer of Holloway Prison in c. 1901, and Acting Assistant Medical Officer of the Port of London in 1904. A year later he suffered a complete breakdown in his health and gave up medicine for authorship.

His first successful stories were the Romney Pringle rogue stories published in Cassell's Magazine in 1902 and 1903,[13] written in collaboration with John James Pitcairn (1860–1936), medical officer at Holloway Prison, and published under the nom de plume "Clifford Ashdown".

In 1905 Freeman published his first solo novel, The Golden Pool, with the background drawn from his own time in West Africa. The hero is a young Englishman who steals a fetish treasure. Barzun and Taylor make the point that while this is a crime, the book is not regarded as crime fiction as according to old notions stealing things from African natives is no crime. Bleiler says it is a colorful, thrilling story, all the more unusual in being ethnographically accurate . . . and that . . . it used to be required reading for members of the British colonial services in Africa.

His first Thorndyke story, The Red Thumb Mark, was published in 1907, and shortly afterwards he pioneered the inverted detective story, in which the identity of the criminal is shown from the beginning. Some short stories with this feature were collected in The Singing Bone in 1912. During the First World War he served as an induction physician and a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps and afterwards produced a Thorndyke novel almost every year until his death in 1943.

Freeman briefly stopped writing at the outbreak of the Second World War, but then resumed writing in an air-raid shelter he had built in his garden. Freeman was plagued by Parkinson's disease in his later years. This makes his achievement all the more remarkable, as in his declining years he wrote both Mr. Polton explains, which Bleiler says . . . is in some ways his best novel,[ and the Jacob Street Mystery (1942) in which Roberts considers that Thorndyke . . . is at his analytical best . . . He was living at 94, Windmill Street, Gravesend, Kent when he died on 28 September 1943.[ His estate was valued at £6,471 5s 11d. Thorndyke was buried in the old Gravesend and Milton Cemetery at Gravesend. The Thorndyke File started a funding drive to erect a granite marker for Freeman's grave, and this was erected in September 1979, with the text: Richard Austin Freeman, 1862 – 1943, Physician and Author, Erected by the friends of "Dr. Thorndyke", 1979.

Political views

Freeman held conservative political views.As early as 1914 in his novel The Uttermost Farthing, the main character espouses views unacceptable today, referring to the "criminal class" as vermin that needed to be exterminated—which the character, Humphrey Challoner, proceeds to do. The motivating factor was Challoner's wife was killed by a burglar whom she caught in the act. Challoner sets himself on the path of revenge. Before he finally happens on the actual perpetrator, he acts as prosecutor, judge, jury, and executioner to kill 24 other men. He then displays their skeletons in his "museum" and processes their heads to shrunken heads, which he keeps hidden.

In his 1921 book Social Decay and Regeneration Freeman put forth the view that mechanization had flooded Britain with poor-quality goods and created a "homogenized, restless, unionized working class". Freeman supported the eugenics movement and argued that people with "undesirable" biological traits should be prevented from breeding through "segregation, marriage restriction, and sterilization". The book also attacked the British Labour movement and criticised the British government for permitting immigrants (whom Freeman referred to as "Sub-Man") to settle in Britain. Social Decay and Regeneration referred to the Russian Revolution as "the Russian catastrophe" and argued society needed to protected from "degenerates of the destructive or" Bolshevik "type." Sections of Social Decay and Regeneration were reprinted in Eugenics Review, the journal of the British Eugenics Society.

Freeman's views on Jews were complex stereotypes. They are clearly set out in his eugenicist book Social Decay and Regeneration (1921). Here Freeman states that of vulgarity the only ancient peoples who exhibited it on an appreciable scale were the Jews and especially the Phoenician.[29] Freeman notes that a large proportion of the Alien Unfit crowding the East End of London, largely natives of Easter Europe are Jews. However, the criticism is of the poor rather than of Jews overall as these unfit aliens were far from being the elect of their respective races.Freeman regards that, through restricting marriage with non-Jews, Jews as having practised racial segregation for thousands of years with the greatest success and with very evident benefit to the race. Not surprisingly, some of these views spill over into his fiction.

Grost states that Helen Vardon's Confession (1922) is another bad Freeman novel suffering from offensive racial stereotypes, Helen Vardon is blackmailed into marrying the fat, old, moneylender Otway, who was distinctly Semitic in appearance, and is surrounded by Jews, to save her father from prison. Otway acts in bad faith, and is grasping, keeping only one servant despite his great wealth. The whole plot is a gratuitously offensive anti-Semitic stereotype. Grost also states that the use of racial stereotypes in The D'Arblay Mystery (1926) marks it as a low point in Freeman's fiction. However, the villain is not Jewish at all, and the only question of stereotypes comes up in the questions about whether the villains (false) hooked nose is a curved Jewish type or, or a squarer Roman nose? There are no anti-Semitic tropes in the book, no grasping money-lender etc. Grost describes Pontifex, Son and Thorndyke (1931), as degenerating into another of Freeman's anti-Semitic diatribes. In this novel the villains are largely Jewish, and come from the community of unfit aliens that Freeman lambastes in Social Decay and Regeneration.[32]

Such offensive representations of Jews in fiction were typical of the time. Rubinstein and Jolles note that while the work of many of the leading detective story writers, such as Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Freeman, featured many gratuitously negative depictions of stereotyped Jewish characters, this ended with the rise of Hitler, and they then portrayed Jews and Jewish refugees in a sympathetic light. Thus with Freeman, the later novels no longer present such gratuitously offensive racial stereotypes, put present Jews much more positively.

In When Rogues Fall Out (1932) Mr. Toke describes the Jewish cabinetmaker Levy as A most excellent workman and a thoroughly honest man, high praise from Freeman's pen. The counsel for Dolby the burglar, a good-looking Jew named Lyon executes a particularly brilliant defence of his client which Thorndyke admires. In Felo de Se; or Death at the Inn (1937) the croupier is described as: a pleasant faced Jew, calm, impassive and courteous, though obviously very much "on the spot". In The Stoneware Monkey (1938) Thorndyke is using a young Jewish man as his messenger. In Mr Polton Explains (1938) Polton is assisted first by the Jewish watchmaker Abraham and then by the Jewish solicitor Cohen comes to Polton's aid not once but twice, not only representing him without cost, but feeding him and loaning him money without interest or term.

Writing

In Bloody Murder, Julian Symons wrote that Freeman's . . . talents as a writer were negligible. Reading a Freeman story is very much like chewing dry straw.[37] Symons then went on to criticise the way in which Thorndyke spoke. De Blacam also noted Thorndyke's ponderous legal phraseology. However, that pedantic ponderousness is the nature of Thorndyke's character. He is a Barrister and used to weighing his words carefully. He never discusses his analysis until he has built the whole picture. Others do not agree with his assessment of Freeman's writing skills. Raymond Chandler, in a 13 December 1949 letter to Hamish Hamilton said: This man Austin Freeman is a wonderful performer. He has no equal in his genre and he is also a much better writer than you might think, if you were superficially inclined, because in spite of the immense leisure of his writing he accomplishes an even suspense which is quite unexpected.

Binyon's also rates Freeman's writing as inferior to Doyle saying Thorndyke might be the superior detective, Conan Doyle is undeniably the better writer.[40] The Birmingham Daily Post considered that Mr. Austin Freeman was not, perhaps, among the finer artists of the short story, and his longer stories could limp, sometimes but that his approach was very effective.

However, de Blacam makes the point that, quite apart from the description of the investigation, each of the descriptions of the crimes in the inverted stories was a fine piece of descriptive writing. Grost agrees that Freeman's descriptive writing is excellent Adey finds that: Freeman’s writing, though lacking Doyle’s atmospheric touch, was clear and concise, with dry humor and a keen eye for deductive detail. Adams agreed that Freeman had considerable powers of narrative description when he stated that Nothing but the author’s remarkable skill in character delineation and graphic narrative could save his stories from being regarded as technical studies for a course on forensic medicine.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating, and Bleiler noted in 1973 that Freeman . . . is one of the very few Edwardian detective story writers who are still read.