|

| 'I'm dependent on the emergence of a voice. I can't make them' Poster by T.A. |

A life in writing: Marilynne Robinson

The Orange prize favourite explains why 'the small drama of conversation' is more interesting to her than adventures writers 'have read about in a brochure'

Interview by Emma BrockesSaturday 30 May 2009 00.01 BST

T

he small town of Gilead, in which two of Marilynne Robinson's three novels are set, is "a dogged little outpost" in Iowa, where her characters live modestly and scorn themselves for staying put. They don't go anywhere, do anything, see anyone besides their neighbours, and the town itself doesn't change - an odd choice of set-up for a novelist, but one that permits her to make a suggestion: that it is people in their kitchens, devastating each other softly and for the most part without intent, that constitutes life at its most indivisible.

Robinson's sporadic output - three novels and two books of non-fiction in 28 years, with a 24-year gap between the first and second novels - is assumed to be a function of ambition, of her painstaking attempt to tell stories through thought and not action. But it's not that at all, she says. When she opens her door in Iowa City, a leafy college town where she teaches creative writing, the 65-year-old doesn't look agonised, or reclusive, or - an expectation raised by her enthusiasm for 18th-century theology and books with the word "Trinitarianism" in the title - in the Joyce Carol Oates school of brittle academics. She is robust, with a steady, amused gaze propped up on high cheekbones and a poodle fussing around her called Otis, so named, she says, because it didn't "seem very poodleish".

If Robinson's first novel, Housekeeping, published in 1980, hadn't been such a huge hit, her reticence would be unremarkable. In light of it, her follow-ups seemed wilfully eccentric: a book about the British nuclear industry, researched while teaching for a year at the University of Kent, and, finally, a second novel, Gilead, told from the point of view of an ailing 76-year-old pastor, considering his mortal and spiritual life. The Reverend Ames is a perversely unmarketable hero - creaking, insular, tormented with unwanted salads left on his porch by the faithful - but Robinson wasn't consciously defying anything in her choice of subject, she says; it was a matter, rather, of not having the "concentration" to behave otherwise. She follows her will. When she writes, she writes quickly, but everything she tried after Housekeeping sounded too similar to interest her. "It might seem a strange thing for me to say, having written Home. But it has to have a central originality in my mind. I'm dependent on the emergence of a voice. I can't make them, they have to come to me. There's no point in my worrying about it."

Home, her third novel, revisits some of the peripheral characters of Gilead. They are not sequential, but companion pieces held together by the friendship of the Reverend Ames and his neighbour, the Reverend Boughton. Structurally, Home is the more conventional novel, the story of Jack, the black sheep of the Boughton family, on his return to his childhood home some 20 years after leaving. His agonising efforts to appease his dying father and establish a relationship with his sister, Glory, are so finely grained, so trembling with a sense of life unlived, and without the neat, redemptive ending of the previous novel, that it is a much stronger and more radical piece.

Robinson's brilliance is in seeing the gaps between words as forcefully as the words themselves; all those rapid calculations as people test an exchange for hidden content, condescension, disingenuousness beyond polite necessity. So few are the external references that it's a while before you realise when the novels are set - in the mid-1950s - and larger themes slowly emerge: civil rights, women's rights, faith and its failure. Gilead won the Pulitzer prize and Home is the favourite for the Orange, announced on Wednesday. "She is one of the most intellectually ambitious novelists in English," says Sarah Churchwell, a lecturer in American literature at the University of East Anglia and one of the Orange judges. "She trusts her readers to be able to think, to appreciate language for its own sake; and while she is morally serious, she is never humourless."

Still, it takes nerve to circumscribe the action of a novel so drastically, and one imagines Robinson reading Gilead back and, with a sudden plunge, thinking what does this amount to? Doesn't she worry at the lack of explosions? She laughs. "There's something in my temperament . . . I have a problem with explosions in the sense that many very fine books are written about things that do, in fact, explode. But if the explosion is something that's supposed to make the novel interesting as opposed to being something that it's essentially about, I think it's very much to be avoided."

It was only after Robinson had finished her PhD that she became aware of "the essential shallowness" of her education. "I would try to write something," she says, "and I would think: I don't know if I really believe that. I don't know what this language means." Before she could even think of attempting fiction, she went on a "very long and intentional" programme of reading, around the Origin of Species, the Decline of the West and the history of political thought. Typically, after reading Das Kapital, she ploughed through Marx's entire bibliography, because she "wanted to see how well he used his sources. And people were just aghast that I would somehow seem to question his authority. It was very odd." Her eyebrows rise in mock incredulity.

She wrote Housekeeping assuming it was too odd to be published, a "liberating" experience. At the time, she was working on a dissertation on Shakespeare's early history plays and would break off to scribble random images on scraps of paper. "I was interested in writing extended metaphors. And so I kept writing these little things and just putting them in a drawer." Somehow, the metaphors proliferated behind her back so that, when she went back to them, they suggested a novel to her; of three generations of women in a town called Fingerbone, grief-stricken, at constant risk of flooding and the resurgence of things long forgotten. "I took out this stack of things and they cohered. I could see what they implied, I could see where the voice was."

Housekeeping is now regarded as a classic. The novel is so disciplined, so full of suppressed longing, that a woman's name whispered under a bridge in the final pages is such a seismic breach of the surface tension that it breaks the reader's heart. Unlike a lot of self-consciously lyrical novels, it forfeits nothing in terms of humour or suspense, although no one goes anywhere in Housekeeping, either. "It seems to me that the small drama of conversation and thought and reflection, that is so much more individual, so much less clichéd than - I mean when people set out on an adventure, I think 90 times out of 100, they've read about it in a brochure. That's not the part of life that interests me." The novel wasn't an instant hit. "It got very good reviews - protective reviews. But the first edition was 3,500 copies and it finely straggled into paperback - there was one bidder. It could have expired."

Through word of mouth Housekeeping grew in popularity and then, in 1987, it was made into a film, directed by Bill Forsyth, with which Robinson was pleased. The novel's origins remain mysterious; the metaphors-in-a-drawer explanation is a hard one to swallow. She won't be more specific. "If I know where an idea's from, I don't use it. It means it has a synthetic quality, rather than something organic to my thinking." The most she will say is that, since the book was written at night while her two young sons slept (she and their father subsequently divorced), she supposes motherhood had some influence. "It changes your sense of life, your sense of yourself." Was it hard to combine the two jobs? "No. I really enjoyed my kids. They were good boys, you know, and interesting. And they didn't wear me out."

Fingerbone was based on the town where she grew up in Idaho, where her father was in the timber business. For the first few years of Robinson's life they lived in the wilds, a vastness of landscape that she is sure "had a huge religious implication for me". Her parents were conventionally religious, no more, and must have been surprised by their daughter's interest in theology. She bursts out laughing. "I think an interest in theology surprises most people. But it was just like a fish to water. It has always been so natural to me."

Robinson made her first attempt at Moby-Dick at the age of nine - people mocked her for carting it around and she finished it to spite them - and then "read my way down the shelf in the library". She did her degree at Brown University and graduate studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. Making a good living wasn't something that concerned her. "I've never aspired in the way people are supposed to aspire. Which is really an enormous help, if you want to write." She still talks to her mother five days a week, for an hour at a time. "She's articulate. She's very funny. She's taller than me. She always had a certain aura - these women who for one reason or another identify with glamour as their native dialect or something."

Robinson says she can't live in a place without knowing "the narrative" behind it, which was a problem when she came to Iowa, as people would say "it has no history. And, you know, you just can't have two or three people gathered together without generating history. So I started reading everything I could find. These little colleges that were founded by abolitionists are often unaware of their origins - that they were integrated schools before the civil war."

This was the basis for Gilead; the historical liberalism of these maligned small towns in the middle west (she eschews the "midwest" shortening, with its snobby baggage) and the casually despised people who live there. It's a fault of language, she suggests, that we allow definitions to take hold - of what constitutes progress, success, happiness - and judge everyone and ourselves by them accordingly. When Robinson talks about relevance, it is in the religious sense that no one person is inherently more valuable than another. She has, from time to time, preached at her Congregationalist church - unsuccessfully to her mind; she gets very nervous. She feels her church is more liberal than the culture around it. "They ordained their first woman in 1853. Before the supreme court decision [to allow gay marriage in Iowa] we blessed gay unions, which is typical of my denomination."

Her novels don't flatter the faithful. Boughton, a sweet man in most respects, whose hair puffs off his head like "the endless work of dreaming", has wholly the wrong opinions about civil rights. A character's childish sense of God as the person who "lived in the attic and paid for the groceries" can never be entirely dispelled, and Glory, Boughton's daughter, describes her faith touchingly in terms of interior decor: "For her, church was an airy white room with tall windows looking out on God's good world, with God's good sunlight pouring in through those windows and falling across the pulpit where her father stood, straight and strong, parsing the broken heart of humankind and praising the loving heart of Christ. That was church." Meanwhile, Ames says, "for me, writing has always felt like praying".

The resurgent science versus religion debate is something Robinson finds absurdly simplistic. She has written on both subjects. Mother Country, her book about Sellafield, seemed like a bizarre change of genre, but she was always interested in the environment. She read a lot of science and economics texts - "the most eccentric passage of my life" - and the resulting polemic, about the dumping of nuclear waste, attracted some cranky reviews in the science press, although she says her findings were hardly startling. "I think they were embarrassed to have a novelist point it out."

In any case, she likes a good fight. Her review of Richard Dawkins's The God Delusion, in Harper's magazine, accuses him of, among other things, philistinism: "He has turned the full force of his intellect against religion, and all his verbal skills as well, and his humane learning, too, which is capacious enough to include some deeply minor poetry." As she told the Paris Review: "He acts as if the physical world that is manifest to us describes reality exhaustively."

Now she says: "I'm not impressed by the quality of Dawkins's writing, or of Christopher Hitchens's writing. If you are up to speed on subjects that they raise, questions come crashing to mind." The religionists haven't helped themselves, though; surely the new atheism is in part a reaction to the rise of, say, Islamic extremism? "Not just Islamic. A lot of Christian extremism has done a great deal to discredit religion; the main religious traditions have abandoned their own intellectual cultures so drastically that no one has any sense of it other than the fringe. These people that attack religion are not attacking any sort of informed cultural sense of religion. They're attacking the crudest." She has never had a live encounter with Dawkins. "I'm a little nervous about live encounters, because everything's a shouting match. I'm thinking of television of course [she doesn't own a television], but so much of it is who can bully, in effect. Not that I couldn't." She smiles dangerously.

She got rather cross with Simon Schama recently for what she saw, in his writings about early Dutch culture, as a faulty sense of Calvinism - "the dear old song of Renaissance Europe" as she calls it - and confronted him on a panel in New York for characterising Calvinists as a bunch of joyless busybodies. "I said, what did you mean by 'Calvinist orthodoxy'? And he said something like 'well I sort of hurried over that part'. You really can't expect everybody to be up to date on Calvin; but at the same time, if you're writing about the Dutch Republic, you ought." Was he embarrassed? "He was serene."

Her rigour is terrifying. In her book of essays, The Death of Adam, Robinson takes issue with the lack of mettle in modern women compared to their antecedents, all the forgotten heroines of the 19th century of whom only Harriet Beecher Stowe is really remembered. What, she says, of orators and abolitionists such as Lydia Maria Child, Lydia Sigourney and Angelina Grimke, all hugely revered and now forgotten? "These women who had so many strikes against them seemed to have so much more self-possession. People will trip over the smallest obstacle now." She continues: "People are enabled by a sense that there is a heritage of women orators. And somehow or other people conspire in erasing history that would be very valuable for them to have."

On a shelf in Robinson's living room is a large framed poster of a quote by President Obama: "For as long as I live, I will never forget that in no other country on earth is my story even possible." It is important to be aware of these things, she says. Look at Iowa, glibly characterised as reactionary but which "had all these splendid deep impulses in its legal system that just sort of got papered over". And on a national scale, too. "Look at major documents and the implications are very large and generous." To remember without over-explaining is the spirit of Robinson's art.

Robinson on Robinson

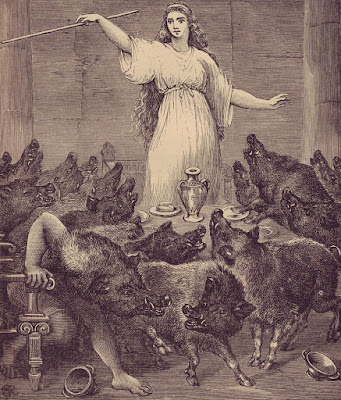

"If there had been snow I would have made a statue, a woman to stand along the path, among the trees. The children would have come close, to look at her. Lot's wife was salt and barren, because she was full of loss and mourning, and looked back. But here rare flowers would gleam in her hair, and on her breast, and in her hands, and there would be children all around her, to love and marvel at her for her beauty, and to laugh at her extravagant adornments, as if they had set the flowers in her hair and thrown down all the flowers at her feet, and they would forgive her, eagerly and lavishly, for turning away, though she never asked to be forgiven. Though her hands were ice and did not touch them, she would be more than mother to them, she so calm, so still, and they such wild and orphan things."

From Housekeeping, published by Faber

It feels to me as though the image in Ruth's mind expresses her sense of the world, as I understand it, very closely. I'm interested in the figural quality of thought, its affinity to myth and dream, first of all in its emotional density and its indifference to time. In this instance the language did more than I intended or anticipated. When a passage carries the memory of this experience, especially vivid for someone relatively new to the writing of fiction, it never ceases to have a certain incandescence whatever its merits may be, objectively considered.

%2B(1).jpg)