|

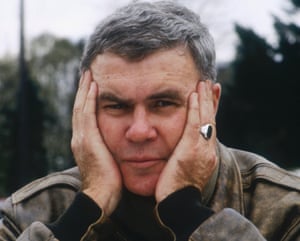

| Haruki Murakami |

The Murakami Effect

On the Homogenizing Dangers of Easily Translated Literature

The following essay originally appeared in Vol. 37, No. 4 of NER.

Stephen Snyder

January 4, 2017

Translation is a kind of traffic, in nearly every sense of the word. There’s the most obvious sense, in that translations cross borders of time, place, and culture, moving from one language into another.

But traffic’s other meaning—that is, the buying and selling of goods—also applies. Translators themselves can be said to traffic in words, sounds, images, and more; whether what is trafficked is tangible or intangible, it’s implied that what is bought, sold, and bartered is in any case commodified. When we think about traffic we also inevitably think about congestion, about impediments to smooth circulation—of vehicles, of course, but also, by extension, of ideas and things. While translations do cross borders, broadening our cultural knowledge as they present one language in the terms of another, they can also become an impediment to free communication. As a translator of contemporary Japanese fiction, I’ve seen both the flow and the congestion, and have witnessed at close range the unintended consequences—and our lack of control as translators—when it comes to the way our texts move or fail to move across borders.