|

| Georges Simenon |

Wednesday, March 30, 2022

Adam, One Afternoon By Italo Calvino

The NEW gardener's boy had long hair which he kept in place by a piece of stuff tied round his head with a little bow. He was walking along the path with his watering-can filled to the brim and his other arm stretched out to balance the load. Slowly, carefully, he watered the nasturtiums as if pouring out coffee and milk, until the earth at the foot of each plant dissolved into a soft black patch; when it was large and moist enough he lifted the watering-can and passed on to the next plant. Maria-nunziata was watching him from the kitchen window, and thinking what a nice calm job gardening must be. He was a grown youth, she noticed, though he still wore shorts and that long hair made him look like a girl. She stopped washing the dishes and tapped on the window.

Tuesday, March 29, 2022

Patricia Highsmith / The Dark Soul of a Writer

|

| Patricia Highsmith |

PATRICIA HIGHSMITH | THE DARK SOUL OF A WRITER

Patricia Highsmith, whose centenary falls on January 19th this year, has become perhaps one of the most influential writers of all time, with her slick twisted dark tales helping to form the foundation of the modern “psychological thriller”. Novelist and critic Gary Raymond takes a look at what makes her work stand out from the rest.

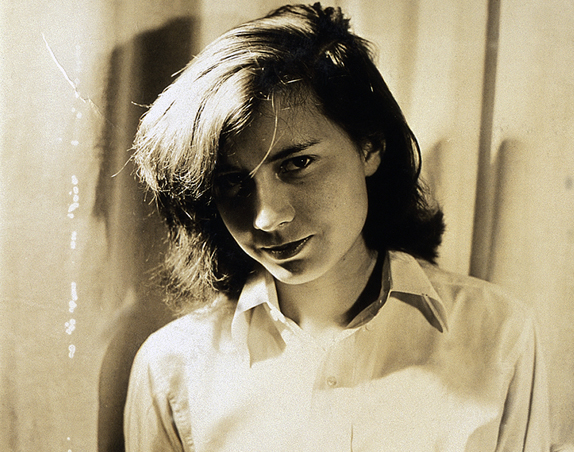

There is a photograph of Patricia Highsmith, famous to those who have ever been interested in her, taken by her friend (and would-be suitor) Rolf Tietgens when she was twenty-one. She is beautiful, yes, and has the look of a very intelligent, prepossessing young woman. But there is something else in that slight upturn of the mouth – you can barely call it a smile – and the twinkle in the eye. Her hair is mussed and pushed to one side. The shadows across her face feel like they are utterly under her control. But you keep coming back to that expression. Mona Lisa, darkness and light, that look she is holding in the centre of the lens, impossible to define; as biographer Joan Schenkar says of Highsmith in it, she has all the allure of the garçonne. I’d go further: it’s as if she’s holding the inescapable excitement of what it is to read all those dark, sadistic books she will ever write in that single frame. It feels facile to say that in that glance you get how she broke the hearts of so many who fell for her, but somehow it also feels important to her story. Patricia Highsmith, who ended up going on to have something of a reputation for being difficult if not out-and-out misanthropy, was an obsessive whose primary preoccupation was with the darker impulses of the human state. She was interested more in that than she ever was in people, and her dedication to and obsession with these Dostoevskian depths is what made her such a mesmerising writer. And somehow, you can see it all in that photo.

What I learned about Patricia Highsmith from writing her biography

|

| Patricia Highsmith Illustration by Triunfo Arciniegas |

What I learned about Patricia Highsmith from writing her biography

By Richard Bradford

Ulster University

Updated / Tuesday, 2 Feb 2021 15:50

Opinion: how did the author's own life and views chime with works like Carol and The Talented Mr Ripley?

Patricia Highsmith was an animal lover, largely because she regarded them as superior to human beings. On one occasion, she declared that if she came upon a famished infant and a starving kitten, she would not hesitate to feed the latter and leave the child to fend for itself.

Patricia Highsmith's low point / Her Diaries and Notebooks reviewed by Richard Davenport-Hines

|

| Patricia Highsmith |

Patricia Highsmith's low point – her Diaries and Notebooks reviewed by Richard Davenport-Hines

BOOKS

BY RICHARD DAVENPORT-HINESPatricia Highsmith's journals brim over with the over-emphatic, incomprehensible and rambling ruminations of an old soak. By Richard Davenport-Hines-

Patricia Highsmith was recently described by a leading American literary critic, Terry Castle, as ‘everyone’s favourite mess-with-your-head morbid misanthrope’ and a ‘mind-blitzingly drunk and hellacious bigot’.

She was also the novelist who achieved early acclaim with Strangers on a Train (1950) and later made the murderous sociopath Tom Ripley into the quasi-hero of five novels.

Monday, March 28, 2022

Patricia Highsmith / After Patricia

HAD PATRICIA HIGHSMITH AND I BECOME PARTNERS IN CRIME?

After Patricia

We’re out this week, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2011 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

Let’s be honest.

I rue the day I didn’t have my late stepmother whacked.

I’d rather eat dirt than talk to my larcenous cousins.

I haven’t forgiven my father for disinheriting me.

I don’t like families.

Patricia Highsmith (1921–95), America’s great expatriate noir novelist (and the subject of my biography, The Talented Miss Highsmith), didn’t like families either. Among twentieth-century writers, only André Gide has more damaging things to say about blood ties than Miss Highsmith does, and Gide is a little more succinct: “Familles, je vous haïs!” But even the Great Counterfeiter himself never went as far as she did on the subject.

The Inner Life of Patricia Highsmith

The Inner Life of Patricia Highsmith

by KATE HART

Monday, August 15, 2011

I opened the first of the American author Patricia Highsmith’s notebooks with trepidation one cloudy day in the Swiss National Library. The austere, modernist library building located just outside the historical center of Bern, Switzerland is the improbable final resting place for Highsmith's literary journals, private diaries, manuscripts, and other personal papers. As an American citizen who was born in Texas and who spent most of her life in the United States, Highsmith made the unconventional decision to leave her literary remains to the Swiss government because of the large sum she was offered (she disparaged the University of Texas at Austin’s proposition of $26,000 as merely "the price of a used car").

Patricia Highsmith in Her Own Words

|

| Patricia Highsmith |

Patricia Highsmith in Her Own Words

Diana Simmonds

February 12, 2014

“"Love is what interests me. And love is indivisible from murder" Joanna/Patricia

Fame and appreciation come and go like the tide – one day they’re in, the next they’re out. Patricia Highsmith is no exception and after some years’ ebb following the success of The Talented Mr Ripley, the tide is again on the turn.

Sunday, March 27, 2022

The Intoxicated Years by Mariana Enríquez

|

| Mariana Enríquez |

The Intoxicated Years

by Mariana Enríquez

Translated by Megan McDowell

1989

That summer the electricity went out for six-hour stretches on the government’s orders; the country didn’t have any more energy, they said, though we didn’t really understand what that meant. Our parents couldn’t get over how the Minister of Public Works had announced the measures necessary to avoid a widespread blackout from a room lit only by a hurricane lamp: like in a slum, they repeated. What would a widespread blackout be like? Would we remain in the dark forever? That possibility was incredible. Stupid. Ridiculous. Useless adults, we thought, how useless. Our mothers cried in the kitchen because they didn’t have enough money or there was no electricity or they couldn’t pay the rent or inflation had eaten away at their salaries until they didn’t cover anything beyond bread and cheap meat, but we girls – their daughters – didn’t feel sorry for them. Our mothers seemed just as stupid and ridiculous as the power outages. Meanwhile, we had a van. It belonged to Andrea’s boyfriend. Andrea was the prettiest of all of us, the one who knew how to rip up jeans to make fabulous cutoffs, and wore crop tops that she bought with money she stole from her mother. The boyfriend’s name doesn’t matter. He had a van he used to deliver groceries during the week, but on weekends it was all ours. We smoked some poisonous pot from Paraguay that smelled like urine and pesticide but was cheap and effective. The three of us would smoke and then, once we were totally out of our minds, we’d get into the back of the van, which didn’t have windows or any light at all because it wasn’t designed for people, it was made to transport cans of garbanzos and peas. We would have him drive really fast, then slam on the brakes, or go around and around the traffic island at the city’s entrance. We had him speed up around corners and make us bounce over speed bumps. And he did it all because he was in love with Andrea and he hoped that one day she would love him back. We would shout and fall on top of each other; it was better than a roller coaster and better than alcohol. Sprawled in the darkness, we felt like every blow to the head could be our last and, sometimes, when Andrea’s boyfriend had to stop because he got held up at a red light, we sought each other out in the darkness to be sure we were all still alive. And we roared with laughter, sweaty, sometimes bloody, and the inside of the truck smelled of empty stomachs and onions, and sometimes of the apple shampoo we all shared. We shared a lot: clothes, the hair dryer, bikini wax. People said that we were similar, that the three of us looked alike, but that was just an illusion because we copied each other’s movements and ways of speaking. Andrea was beautiful, tall, with thin and separated legs; Paula was too blond and turned a horrible shade of red when she spent too long in the sun; I could never manage a flat belly or thighs that didn’t rub together – and chafe – when I walked.

Mariana Enriquez on the Fascination of Ghost Stories

|

| Mariana Enríquez |

Mariana Enríquez on the Fascination of Ghost Stories

December 12, 2016

In “Spiderweb,” your story in this week’s issue, an already sour relationship is tested by a road trip north to Paraguay. For you, is there a particular significance to the characters’ journey into the north? Or is there a more general idea of the north that Argentines might have? The story notes that things take longer to disappear there.

Saturday, March 26, 2022

Notes on Craft by Mariana Enríquez

Notes on Craft by Mariana Enríquez

Translated by Josie Mitchell

Mariana Enríquez is a novelist, journalist and short-story writer from Argentina. Things We Lost in the Fire, translated by Megan McDowell, is her first book to appear in English, published by Portobello Books in 2017. In this series, we give authors a space to discuss the way they write – from technique and style to inspirations that inform their craft.

Our Lady of the Quarry by Mariana Enriquez

Our Lady of the Quarry by Mariana Enriquez

(Translated, from the Spanish, by Megan McDowell.)

December 14, 2020

Silvia lived alone in a rented apartment of her own, with a five-foot-tall pot plant on the balcony and a giant bedroom with a mattress on the floor. She had her own office at the Ministry of Education, and a salary; she dyed her long hair jet black and wore Indian blouses with sleeves that were wide at the wrists and silver thread that shimmered in the sunlight. She had the provincial last name of Olavarría and a cousin who had disappeared mysteriously while travelling around Mexico. She was our “grownup” friend, the one who took care of us when we went out and let us use her place to smoke weed and meet up with boys. But we wanted her ruined, helpless, destroyed. Because Silvia always knew more: if one of us discovered Frida Kahlo, oh, Silvia had already visited Frida’s house with her cousin in Mexico, before he vanished. If we tried a new drug, she had already overdosed on the same substance. If we discovered a band we liked, she had already got over her fandom of the same group. We hated that her long, heavy, straight hair was colored with a dye we couldn’t find in any normal beauty salon. What brand was it? She probably would have told us, but we would never ask. We hated that she always had money, enough for another beer, another ten grams, another pizza. How was it possible? She claimed that in addition to her salary she had access to her father’s account; he was rich, she never saw him, and he hadn’t acknowledged paternity, but he did deposit money for her in the bank. It was a lie, surely. As much a lie as when she said that her sister was a model: we’d seen the girl when she came to visit Silvia and she wasn’t worth three shits, a runty little skank with a big ass and wild curls plastered with gel that couldn’t have looked any greasier. I’m talking low-class—that girl couldn’t dream of walking a runway.

Friday, March 25, 2022

The Master and Margarita by Bulgakov / Poetry in the Novel

Besides many musical themes, Bulgakov also presents lines of poetry in The Master and Margarita. Sometimes they are quoted by the characters, sometimes they are heard in the background. The poems they come from are written by Aleksander Sergeevich Pushkin (1799-1837), without any doubt the most popular Russian poet ever, and by Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (1893-1930), a contemporary of Bulgakov with whom he had a love-hate relationship.

Bulgakov / Patriarch's ponds

Thursday, March 24, 2022

The battle for Bulgakov's nationality

|

| Mikhail Bulgakov |

The battle for Bulgakov's nationality

Kelly Nestruck

Thu 11 Dec 2008 15.21 GMT

Few would disagree that Mikhail Bulgakov is a great writer. But is the man who wrote Flight and A Cabal of Hypocrites a great Russian writer, or a great Ukrainian writer? Or, can any country that exists today really lay full claim to him?

Books and writers / Bulgakov

|

| Mikhail Bulgakov |

| Mikhail Bulgakov (1891-1940) |

Ukrainian journalist, playwright, novelist, and short story writer, whose major work was the Gogolesque fantasy The Master and Margarita. In the story the Devil visits Stalinist Moscow to see if he can do some good. The book is considered a major Russian novel of the 20th century. It first appeared in a censored form in the Soviet journal Moskva in 1966-67. Bulgakov used satire and fantasy also in his other works, among them the short story collection Diaboliad (1925). |

Books and writers / Gogol

|

| Nikolai Gogol Ilustration by Pablo García |

(1809-1852) Nikolai (Vasilyevich) Gogol |

Great Ukrainian novelist, dramatist, satirist, founder of the so-called critical realism in Russian literature, best-known for his novel Mertvye dushi I-II (1842, Dead Souls). Gogol's prose is characterized by imaginative power and linguistic playfulness. As an exposer of grotesque in human nature, Gogol could be called the Hieronymus Bosch of Russian literature. |

Books and writers / Anna Akhmatova

|

| Anna Akhmatova |

| Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966) Pseudonym of Anna Andreyevna Gorenko |

One of the greatest Ukrainian poets of the 20th-century, who became a legend in her own time as a poet and symbol of artistic integrity. Anna Akhmatova's work is characterized by precision, clarity, and economy. She wrote with apparent simplicity and naturalness and her rhyming was classical compared to such radical contemporary writers as Marina Tsvetaeva and Vladimir Mayakovsky. |

Wednesday, March 23, 2022

Books and writers / Maksim Gorky

|

| Maksim Gorky |

(1868-1936)

Pseudonym Gorky means "bitter", originally Aleksei Maximovich Peshkov

Books and writers / Chekhov

|

| Anton Chekhov |

Russian playwright and one of the great masters of modern short story. In his work Chekhov combined the dispassionate attitude of a scientist and doctor with the sensitivity and psychological understanding of an artist. Chekhov portrayed often life in the Russian small towns, where tragic events occur in a minor key, as a part of everyday texture of life. His characters are passive by-standers in regard to their lives, filled with the feeling of hopelessness and the fruitlessness of all efforts. "What difference does it make?" says Chebutykin in Three Sisters.

Books and writers / Osip Mandelstam

Osip (Emilevich) Mandelstam

(1891-1938)

also: Osip Mandel'shtam

Russian poet and essayist, who is regarded alongside Boris Pastenak, Marina Tsvetaeva and Anna Akhmatova as one of the greatest voices of the 20th-century Russian poetry. Most of Mandelstam's works were unknown outside his own country and went unpublished during the Stalin era (1929-53). Along with Anna Akhmatova, Mandelstam was one of the foremost members of Acmeist school of poetry. His early works were impersonal but later he also analyzed his own experiences, history, and the current events.

Tuesday, March 22, 2022

How many Russian soldiers have died in the war in Ukraine?

Analysis: Some say the country’s losses could rival those of its wars in Chechnya or Afghanistan

Andrew Roth

Tue 22 March 2022

It has been three weeks since Russia updated the official death toll to its invasion in Ukraine, leaving open the question of how many of its soldiers have been killed or wounded in the chaotic opening stages of its war.

Cannibalism and genocide / The horrific visions of Ukraine’s best loved artist

|

| Feed me … one of Prymachenko’s works which c |

Cannibalism and genocide: the horrific visions of Ukraine’s best loved artist

Friday 18 March 2022

At the 1937 International Exposition in Paris, two colossal pavilions faced each other down. One was Hitler’s Germany, crowned with a Nazi eagle. The other was Stalin’s Soviet Union, crowned with a statue of a worker and a peasant holding hands. It was a symbolic clash at a moment when right and left were fighting to the death in Spain. But somewhere inside the Soviet pavilion, among all the socialist realism, were drawings of fabulous beasts and flowers filled with a raw folkloric magic. They subverted the age of the dictators with nothing less than a triumph of the human imagination over terror and mass death.

Monday, March 21, 2022

Five incredible books / How did writer Ludmila Ulitskaya become a modern-day classic?

Ludmila Ulitskaya

Five incredible books:

How did writer

Ludmila Ulitskaya

become a modern-day classic?

Alexandra Guzeva

FEB 21 2018

Imagine if all the great classic writers of the past were reincarnated in one intelligent woman? Her bestselling novels depict love and death, people in different jobs and ages, as well as Soviet and modern Russian realities.

A Review of Daniel Stein, Interpreter by Ludmila Ulitskaya

|

| Ludmila Ulitskaya |

Translated from the Russian by Arch Tait

(New York, NY: Overlook Press, 2011)

Miracles abound in Ludmila Ulitskaya’s new novel, Daniel Stein, Interpreter. Early on, Daniel Stein—a young Polish priest who has been forced to become a translator for the occupying Nazis—organizes the escape of 300-some members of a condemned Jewish ghetto. The breakout, which takes place on the eve of the prisoners’ execution, succeeds against all odds. I had a hard time believing it.

Daniel Stein, Interpreter by Ludmila Ulitskaya

Daniel Stein,Interpreter

by Ludmila Ulitskaya

Part 1: Review

It's a strange way to tell a story. Daniel Stein: Interpreter is a patchwork of letters, diaries, official notes, reports and recorded speeches that seem to both hide and explore the extraordinary tale of Daniel, formerly Dieter Stein, the interpreter of the title. He does emerge in the end, a redemptive, compassionate person with an unshakable resolve to save people from destruction - whether it's brought upon them by the unimaginable cruelties of the Holocaust, the Soviet occupation or the individual cruelties of everyday lives.

|

| Ludmila Ulitskaya |

Born a Polish Jew, Stein survived the Germans and the Soviets by becoming an interpreter seemingly serving both, but in reality serving only his own desire to do good. He was baptized a Christian by nuns who hid him from the Nazis. He became a Carmelite monk and decided to work for his God in, of all places, Israel, where Christianity began with the Jewish Jesus, his Jewish relatives and first followers. He is an unusual monk for the Catholic Church (even for the Polish Pope) and for the Israelis who don't accept him as a Jew and are suspicious of his conducting mass in Hebrew.

Sunday, March 20, 2022

Interview / Ludmila Ulitskaya

|

| Ludmila Ulitskaya |

INTERVIEW: LUDMILA ULITSKAYA

PEN: Several of the questions raised in Daniel Stein, Interpreter touch upon very sensitive issues, not just in Russia but globally. However, tolerance—ethnic, religious—seems to be a particular pressure point in today’s Russia (especially if you follow the stories in the U.S. media). Do you see this as an alarming problem or is the matter exaggerated?