|

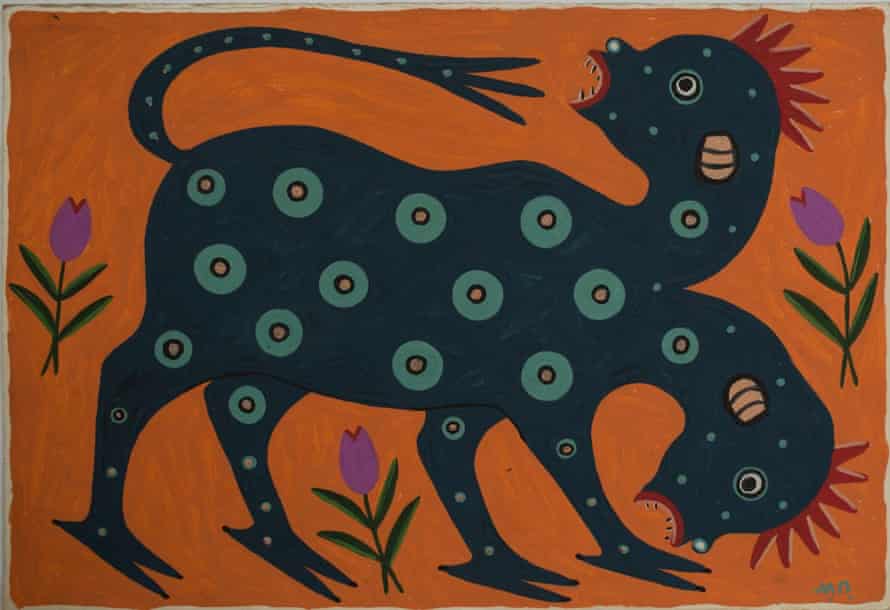

| Feed me … one of Prymachenko’s works which c |

Cannibalism and genocide: the horrific visions of Ukraine’s best loved artist

Friday 18 March 2022

At the 1937 International Exposition in Paris, two colossal pavilions faced each other down. One was Hitler’s Germany, crowned with a Nazi eagle. The other was Stalin’s Soviet Union, crowned with a statue of a worker and a peasant holding hands. It was a symbolic clash at a moment when right and left were fighting to the death in Spain. But somewhere inside the Soviet pavilion, among all the socialist realism, were drawings of fabulous beasts and flowers filled with a raw folkloric magic. They subverted the age of the dictators with nothing less than a triumph of the human imagination over terror and mass death.

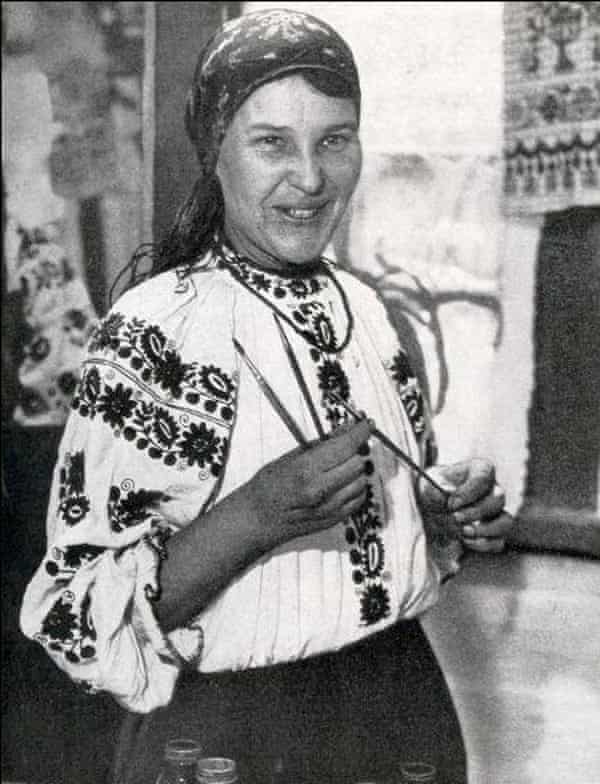

These sublime creations were the work of a Ukrainian artist, Maria Prymachenko, who has once again become a symbol of survival in the midst of a dictator’s war. Prymachenko, who died in 1997, is the best-loved artist of the besieged country, a national symbol whose work has appeared on its postage stamps, and her likeness on its money. Ukrainian astronomer Klim Churyumov even named a planet after her.

When the Museum of Local History in Ivankiv caught fire under Russian bombardment, a Ukrainian man risked his life to rescue 25 works by her. But Prymachenko’s entire life’s work is now under much greater threat. As Kyiv endures heavy attacks, 650 paintings and drawings by the artist held in the National Folk Decorative Art Museum are at risk, along with everything and everyone in the capital.

It’s said that, when some of Prymachenko’s paintings were shown in Paris in 1937, her brilliance was hailed by Picasso, who said: “I bow down before the artistic miracle of this brilliant Ukrainian.” It would make artistic sense. For this young peasant, who never had a lesson in her life, was unleashing monsters and collating fables that chimed with the work of Picasso, and his friends the surrealists. While the dictatorships duked it out architecturally at that International Exhibition, Picasso unveiled Guernica at the Spanish pavilion, using the imagery of the bullfight to capture war’s horrors. Prymachenko, too, dredged up primal myths to tackle the terrifying experiences of Ukrainians.

Her pictures from the 1930s are savage slices of farmyard vitality. In one of them, a beautiful peacock-like bird with yellow body and blue wings perches on the back of a brown, crawling creature and regurgitates food into its mouth. Why is the glorious bird feeding this flightless monster? Is it an act of mercy – or a product of grotesque delusion? In another drawing, an equally colourful bird appears to have its own young in its mouth. Carrying it tenderly, you might think, but only if you know nothing of the history of Ukraine.

At first sight, Prymachenko might seem just colourful, decorative and “naive”, a folkloric artist with a strong sense of pattern. Certainly, her later post-1945 works are brighter, more formal and relaxing. But there is a much darker undertow to her earlier creations. For Prymachenko became an artist in the decade when Stalin set out to destroy Ukraine’s peasants. Rural people starved to death in their millions in the famine he consciously inflicted on Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933.

Initially, food supplies failed because of the sudden, ruthless attempt to “collectivise” agriculture. Peasants were no longer allowed to farm for themselves but were made to join collectives in a draconian policy that was meant to provide food for a new urban proletariat. Ukraine was, and is, a great grain-growing country but the shock of collectivisation threw agriculture into chaos. The Holodomor, as this terror-famine is now called, is widely seen as genocide: Stalin knew what was happening and yet doubled down, denying relief, having peasants arrested or worse if they begged in cities or sought state aid. In a chilling presage of Putin’s own logic and arguments, this cruelty was driven by the ludicrous notion that the hungry were in fact Ukrainian nationalists trying to undermine Soviet rule.

“It seems reasonable,” writes historian Timothy Snyder in his indispensable book Bloodlands, “to propose a figure of approximately 3.3 million deaths by starvation and hunger-related disease in Soviet Ukraine in 1932-1933”. These were not pretty deaths and they took place all around Prymachenko in her village of Bolotnya. Some people were driven to cannibalism before they died. The corpses of the starved in turn became food.

Born in 1908, Prymachenko was in her early 20s when she witnessed this vision of hell on Earth – and survived it to become an artist. But the fear did not end when the famine did. Just as her work was sent to Paris in 1937, Stalin’s Great Terror was raging. It is often pictured as a butchery of urban intellectuals and politicians – but it came to the Ukrainian countryside, too.

So it would take a very complacent eye not to see the disturbing side of Prymachenko’s early art. The bird in its parent’s mouth, the peacock feeding a brute. Maybe there is also survivor guilt, and a feeling of alienation from a destroyed habitat, in such images of strange misbegotten creatures lost in a nature they can’t work and don’t comprehend. One of her fantastic beasts appears blind, its toothy mouth open in a sad lamentation, as it stumbles through a garden on four numbed clodhopping feet. A serpent and a many-headed hydra also appear among the flowers, like deceptively beautiful, yet murderous intruders in Eden. In another of these mid-1930s works, a glorious bird rears back in fear as a smaller one perches on its breast, beak open.

There’s nothing decorative or reassuring about the images that got this brave artist noticed. Far from innocently reviving traditional folk art, her lonely or murderous monsters exist in a nature poisoned by violence. Yet she got away with it – and was even officially promoted right in the middle of Stalin’s Terror, when millions were being killed on the merest suspicion of independent thought. Perhaps this was because even paranoid Stalinists didn’t think a peasant woman posed a threat.

Prymachenko remembered that, as a child, she was one day tending animals when she “began to draw real and imaginary flowers with a stick on the sand”. It’s an image that recurs in folk art – this was also how the great medieval painter Giotto started. But it was Prymachenko’s embroidery, a skill passed on by her mother, that first got her noticed and invited to participate in an art workshop in Kyiv. Such origins would inevitably have meant being patronisingly classed by the Soviet system as a peasant artist. An “intellectual” who produced such work could have ended up in the gulag or worse.

Yet, to see the sheer miracle of her achievement, you must also set Prymachenko in her time as well as her place. The Soviet Union in the 1930s was relentlessly crushing imagination as Stalin imposed absolute conformity. The Ukrainian writer Mikhail Bulgakov couldn’t get his surreal fantasies published, even though, in a tyrannical whim, Stalin read them himself and spared the writer’s life. But the apparent rustic naivety of Prymackenko’s work let her create mysterious, insidiously macabre art that had more in common with surrealism than socialist realism.

Then, incredibly, life in Ukraine got worse. Prymachenko had found images to answer famine but she fell silent in the second world war, when Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union made Ukraine one of the first places Jews were murdered en masse. In September 1941, 33,771 Kyiv Jews were shot and their bodies tossed into a ravine outside their city. Prymachenko was working on a collective farm and had no colours to paint.

In the 1960s, she was the subject of a liberating revival, her folk designs helping to seed a new Ukrainian consciousness. There’s an almost hippy quality to her 60s art. You can see how it appealed to a younger audience, keen to reconnect with their Ukrainian identity.

The country has other artists to be proud of, not least Kazimir Malevich, a titan of the avant garde famous for Black Square, the first time a painting wasn’t a painting of something. Yet you can see why Prymachenko is so loved. Her art, with its rustic roots, expresses the hope and pride of a nation. But the past she evokes is no innocent age of happy rural harmony.

What she would make of Putin’s terror one can only guess and fear.

THE GUARDIAN

No comments:

Post a Comment