HAD PATRICIA HIGHSMITH AND I BECOME PARTNERS IN CRIME?

After Patricia

We’re out this week, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2011 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

Let’s be honest.

I rue the day I didn’t have my late stepmother whacked.

I’d rather eat dirt than talk to my larcenous cousins.

I haven’t forgiven my father for disinheriting me.

I don’t like families.

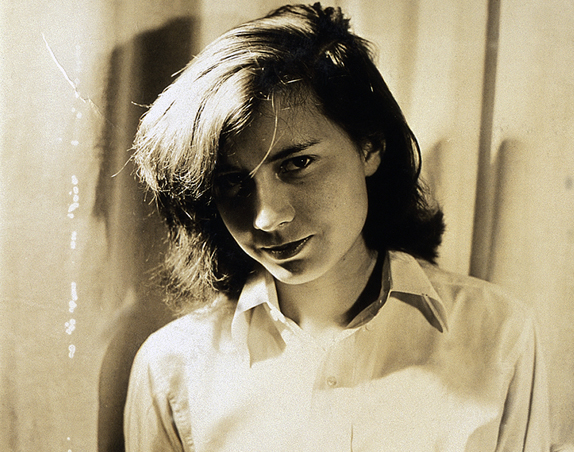

Patricia Highsmith (1921–95), America’s great expatriate noir novelist (and the subject of my biography, The Talented Miss Highsmith), didn’t like families either. Among twentieth-century writers, only André Gide has more damaging things to say about blood ties than Miss Highsmith does, and Gide is a little more succinct: “Familles, je vous haïs!” But even the Great Counterfeiter himself never went as far as she did on the subject.

Sitting in the second-floor study of her stone farmhouse in the village of Moncourt, France, her body hunched in front of her scrolled, roll-top desk like a snail confronting its shell, the fifty-one-year-old Patricia Highsmith picked up her favorite Parker fountain pen on a summer’s day in 1972 and confided her feelings about families to her notebook:

One situation—one alone, could drive me to murder: family life, togetherness.

A year and a half later, Highsmith was circling her wagons again around the same thought by way of a nice, organizing little list. Like almost everything she turned her hand to her, her list—“Little Crimes for Little Tots,” she called it—has murder on its mind, focuses on a house and its close environs, mentions a mother in a cameo role, and is highly practical in a thoroughly subversive way. It’s also vintage Highsmith: the writer who entertained homicidal feelings for her stepfather since grade school looks at six-year-olds and sees only the killers inside them.

Still, in spite of our shared opinion of family life, in spite of my growing admiration for the extremity of her writing voice (here she is as a coed: “Obsessions are the only things that matter. Perversion interests me most and is my guiding darkness”), in spite of the fact that she had the most fascinatingly complicated psychology I’d ever kept company with—living and writing in Highsmith’s cone of watchful darkness was giving me plenty of trouble, harrowing my feelings and upending my sense of myself.

She was ambivalent and extreme in everything she thought, felt, and did—running the political gamut from communist to fascist to liberal to libertarian and back again, often in the same week. Love and death, or rather, love and murder were the motives for her metaphors: she died for love a thousand times in life and killed for it over and over again in her fiction. She approached her many lovers—beautiful, intelligent women but also a few interesting men—with a wedding bouquet in one hand and a headsman’s axe in the other. From the age of twelve, she thought of herself as a boy in a girl’s body, but was insulted when French waiters directed her to the men’s room.

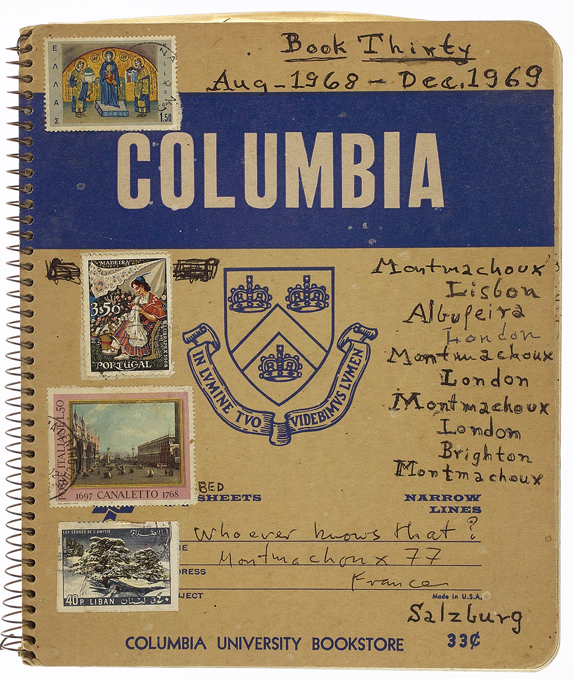

Then, too, her work habits lent a new dimension to the terms obsession and compulsion. For decades, five to eight typed pages of a novel or a short story rolled each day from the platen of her favorite coffee-colored Olympia Deluxe Portable typewriter, not to mention the thousands of letters and hundreds of articles. She did countless books of drawings, made sculptures, constructed assemblages. She crafted a great deal of handmade furniture. She gardened, she whittled, she pasted up her own Christmas cards. She had always to be doing something.

And, just my luck, she was both alcoholic and hypergraphic, leaving a trail of crushed hearts, bruised feelings, and total blackouts behind her—as well as eight thousand pages of handwritten notebooks and diaries, sixteen fat press books, countless photograph albums, two hundred and fifty unpublished manuscripts, and thirty published works.

HIGHSMITH

Life in Highsmith Country—my residency there would eventually stretch to eight years—was grinding me down. The sheer size of her archives meant I had to go into marathon sessions of reading and thinking around the clock. I interviewed nearly three hundred people in five countries and several North American states. I wrote for fifteen and sixteen hours a day. I developed blurred vision and two small ulcers (which, in case there was any doubt as to their origin, disappeared the day I turned in my manuscript). The tendons in my wrists and thumbs swelled up and stayed that way. My bad back got worse. I complained bitterly—and went on working.

Meanwhile, Highsmith’s novels—brilliantly disorienting narratives of such shimmering negativity (Strangers on a Train, The Talented Mr. Ripley, This Sweet Sickness, The Blunderer, Deep Water, et al.) that they are like nothing else in their literary landscape—were exercising their well-known ability to suck another reader into their bottomless vortex of moral relativities, transferable guilts, and unstable identities. And her life—more than a little on the psychopathic side, with an adept’s taste for transgression—was forcing me to turn a coroner’s eye on some dubious tendencies in my own character.

Who was that masked woman toying, however briefly, with the idea of secretly recording a tape-shy witness in crucial conversations about Highsmith? (Alas, it was me, thrilled and guilted by the possibility of getting the goods verbatim.) Shouldn’t my own faintly criminal love history have recused me from judging Highsmith’s happy habit of triangulating her affairs: repeatedly seducing her lover’s lovers—and those lovers’ lovers as well? (It should have, but I caught myself smugly judging her all the same.) Why was I, a writer whose belief in privacy is practically a religion, using information for my book from photographs that were taken without Highsmith’s permission? (Because the photos were handed to me and they were interesting is the uncongenial answer.)

Highsmith’s personal magnetism and dark materials had always exerted a sublunary pull on friends, fans, and lovers. Against their better judgment, some of them told me, they caught themselves acting just like characters in a Highsmith novel. And now I was doing the same thing: conspiring in a version of Highsmithian behavior in order to write my book—well, that was my excuse, anyway. But it was making me very unhappy—with her. And the prejudices I was building up against her own gaudy prejudices exhausted me.

Plus, Highsmith was sending strong signals from beyond the grave—in the form of darkly colored dreams stage managed in Highsmith Country and starring both of us—that she didn’t much care for living with me, either. Our relationship, intolerably intimate, was also alive with all of her favorite ambiguities—no mean feat considering one of us was dead. And I was discovering daily—and in greater detail than I wanted—just how much of her life she’d spent reviling at least four of the groups into which I loosely fit by birth and affinity. (One of these groups was “women,” another was “Jews.”)

Highsmith had also managed to provide me with perhaps the most unusual hour of my writing life. After months of steady application to the Highsmith literary trustees in Zurich, I’d finally received permission to read the sulphurous Highsmith diaires, in which, separate from her writing journals, Highsmith had kept close accounts of dozens of her hundreds of love affairs.

In a celebratory mood, I ordered the diaries up from the cellars of the Swiss National Library, opened one of them at random, and was shell-shocked to find a name I knew very well: the name of the brilliant, elderly, dignified woman who, shortly before her death in the 1980s, had been my play agent in New York. I’d had no idea of her sexual identity and had always preferred to think of my agents as fully-clothed and at their desks. And now, half a world away and burning through the letters of Highsmith’s crabbed handwriting were the richly explicit—and deeply colorful—physical details of this woman’s torrid love affair with Highsmith in the 1940s. It’s a description I’m still hoping to forget.

And there was something else as well. Highsmith’s default activities—the stalking of her lovers, the rifling of their lives and her own for her fictions, the reordering of chronologies and circumstances in her diaries and journals to suit herself and/or her imagined posterity—were beginning to remind me of the darker side of the biographer’s art.

Despite the much-quoted definition of biographers as “artists on oath” (by Desmond McCarthy, the laziest member of the Bloomsbury group), the techniques employed by authors whose business it is to write about the specific gravity of human character are at least descriptively criminal: we stalk our subjects; we treat their lives as crime scenes; we invade their stately homes; we rifle their archives; we elicit and expose their intimacies; and run our imaginations over everything else—all in the ostensible service of the debt Voltaire claimed the living owe the dead: “the truth,” in each of its manifestations. The shadow of the “publishing scoundrel” who narrates The Aspern Papers hangs over us all.

But Highsmith’s eccentric behavior and criminal imagination—coupled with a hard look at my own circumstances—ended by persuading me that within the delicate balance of competing truths that biography is always on the verge of upsetting, the living and the dead should be offered a little protection from each other, should offer each other a little protection. It is, after all, the premise on which creative partnerships are founded.

For at some point during my long, excruciating, rivetingly interesting relationship with this dead writer, we had somehow agreed to collaborate in rendering the trespasses of her life and the extremities of her work. By now, enough of her identity has leaked through the porous borders of her writing to perfuse my own, and I’ve been issued a passport to Highsmith Country that can never be revoked.

You might say—she would certainly say it—that Patricia Highsmith and I have become partners in crime.

Joan Schenkar is the author of The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith.

No comments:

Post a Comment