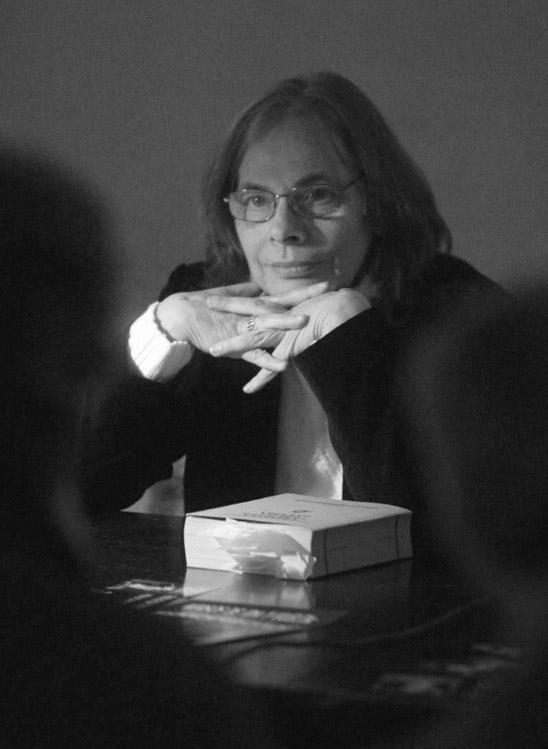

Cristina Peri Rossi is the only woman associated with the Latin American Boom, which gained prominence in the 1970s. Peri Rossi, a first-rate author from Uruguay, had everything to be on par with the Boom authors: she was actively involved in the causes they supported during the ’60s and ’70s, was exiled for her political militancy twice, and was a close friend of Julio Cortázar’s. Her association with the Boom, though, is partial. It’s not that she didn’t share the penchant for fantastic literature that characterized a few of the Boom generation’s more prominent members—García Márquez and Cortázar, for instance. Mario Vargas Llosa never dabbled in this genre either and he has always been one of the Boom’s key writers. Peri Rossi’s writing—she has published over 37 novels, short-story collections, and poetry books, and is a journalist and political commentator for the public radio station Catalunya Ràdio—is as great as theirs. It’s that she either lacked or manifested (depending on who’s keeping score) something in excess: she is a woman.

I don’t know if the lines I have written will irritate Peri Rossi; it is likely that they might. Her pages invariably defy commonplaces, formulas, and literary conventions, including those of genre. I quote her: “Having is illusory, my dear. Whatever we have is determined by others. Because of this, I offer a dream. I’ll be what you want me to be: man or woman.”

In response to her possible irritation, I’d argue: “I’m not saying that you are a feminine author, because you’re not. In its execution, your prose is endowed with masculinity, and your poems and their subject matter manifest a formal, androgynous will. What I’m saying is that you’ve been unfairly put aside, and if any association between you and the Boom remains, it’s because you’ve been impossible to erase. How can an author of your caliber be left out from the roster of its generation?”

We spoke about Montevideo and her fiction via Skype—she is a Uruguayan writing in Barcelona, where she has lived for decades, and I am a Mexican writing in Brooklyn, where I have resided the last seven years.

SATURDAY NIGHT

In the solitary dawn

through drifting secondhand smoke

and sidewalks sticky with spit

I go out walking

to escape the nocturnal silence of my room

seeking bright lights

oh, those neon friends who always ward off

my internal wolves

my hungry demons

(my Vallejo ancestors).

I go in search of something

losing myself in the narrow streets round the harbor

looking for company,

oh, the sweet drugs that since Baudelaire

have run along the gutters of cities at nighttime

—London, Paris, New York, Madrid—

oh, the unknown flesh that stirs, aroused by a look.

Finally I find it: some sleazy joint that’s still open

a prison cell of solitary pleasures

a peep show hidden between the trees:

a bookstore open all night

where I can wallow among the books

luxuriate in other people’s verses

and finally reach orgasm

with one of Allen Ginsberg’s self-destructive poems.

through drifting secondhand smoke

and sidewalks sticky with spit

I go out walking

to escape the nocturnal silence of my room

seeking bright lights

oh, those neon friends who always ward off

my internal wolves

my hungry demons

(my Vallejo ancestors).

I go in search of something

losing myself in the narrow streets round the harbor

looking for company,

oh, the sweet drugs that since Baudelaire

have run along the gutters of cities at nighttime

—London, Paris, New York, Madrid—

oh, the unknown flesh that stirs, aroused by a look.

Finally I find it: some sleazy joint that’s still open

a prison cell of solitary pleasures

a peep show hidden between the trees:

a bookstore open all night

where I can wallow among the books

luxuriate in other people’s verses

and finally reach orgasm

with one of Allen Ginsberg’s self-destructive poems.

—Cristina Peri Rossi

Translated by tatiana de la tierra

Carmen Boullosa You were born in Montevideo, the daughter of Italian immigrants?

Cristina Peri Rossi Both of my parents are the descendents of Italian immigrants, yet at home, only Spanish was spoken. Montevideo was a city of immigrants—everyone was the child, grandchild, or great-grandchild of Italians or Jews who fled during World War II, or came with other emigrations during the Spanish Civil War or the Armenian-Turkish war.

CB Were you raised in a family of readers?

CPR My mom—who is still around, I am fortunate, she is 92—was a teacher and the only one at home who had studied, and yes, she did read to me. She tells me that she used to read out loud to me when she was pregnant, and that we’d listen to a lot of music. That might be why I like music so much. To say that I am a writer for this reason, however, is more uncertain. What is true is that she told me that one day, we got on a bus and I surprised her because I began to read an ad out loud. She says that I began to speak fluently very early. And that she said to herself, “What bad luck, she’s going to be a writer!”

CB Was it a kind of golden age of literature? Tell us about this Montevideo in which youbecame a writer, or in which you received your formation as a young writer.

CPR Montevideo had its time of splendor a little before I was born. The so-called boom years of Uruguay correspond to the period of World War II, when the Uruguayan peso was on par with the dollar. Later, when the war ended, beef and wool, the main Uruguayan exports, plummeted in value because the purchasing countries became producers: the United States, for example. Thereafter industrial development was halted, the government had a huge debt with the IMF, the inflation rate reached 100 percent, and the pauperized middle class all but disappeared.

CB Uruguay and Argentina stopped serving as the world’s granary and stable.

CPR I am from a very humble family. My mother was a teacher and my father was a worker. He was also a farmer who immigrated to the city, with the drama that is common to all displaced farmers: they never stop missing the country and never completely become urbanites. Back then we had financial concerns at home, but I was able to study because the social democratic government made free, secular education available to everyone. I would spend my time jotting down the books I wanted to read and visiting bookstores, but buying little because I didn’t have money. I’ve always been a great reader in libraries. At the National Library I read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex at 16.

CB Were the libraries good in Montevideo?

CPR The National Library is an excellent library. And the bookstores were also excellent and—something that was always fascinating to me, and which I’ve only seen again in New York—they were open all night. Cafés and record stores as well. I, who, as my mother says, am a night owl, could spend the night between cafés, where I was likely to encounter prostitutes playing chess, perhaps, or the drunken men who exploited them, next to a chess or math teacher who recited Baudelaire in French. It was a bohemian world, one that has always captivated me, and a world of losers as well, because to be Uruguayan is a very odd thing. I’d say that Uruguayans who got off the boats are Italians who speak Spanish but possess French culture, a capitalist economy, and, on the other hand, Arab generosity. So we are a very diverse mix. But yes, for me it was fascinating, for example, to spend two or three hours in one of the great bookstores of Montevideo, looking at those books that I was never going to buy. When I was around 17, I used to go to one owned by a Spanish exile. One day I discovered a book with an intriguing title in the window display: The Ballad of the Sad Café by Carson McCullers. I entered and asked the price and it seemed unattainable to me. I made the greatest sacrifice I could at the time: I stopped smoking for a month—back then I was a smoker, and that month was the worst of my life—in order to buy the book. I also walked to and from the university for that entire month. The book is still one of my favorites.

CB When you left Montevideo, you already had a 3,000-volume library.

CPR Unfortunately I lost it. I had to leave that entire first library behind because I had to flee very quickly, in 24 hours, shortly before the military coup. The military had kidnapped a student who had stayed at my house. I left my apartment, exactly as it was, and later had to sell it because by then the dictatorship had issued a decree with which it expropriated the apartments of people who had fled.

CB But you managed to save the apartment?

CPR I sold it off cheaply, from Spain. I practically had to give it away, because it was known that if I did not, it would be handed over to the military. My family did not keep the library. They were afraid and thought that it would jeopardize them, as the military were looking for me and my nationality had been revoked.

CB For a writer it is very important to save and treasure things, but also to let go.

CPR In order to keep writing, I need to forget what I’ve written. And it’s true to such an extent that sometimes it happens to me on radio programs, or with people writing a thesis, that they quote some lines and they ask me who the author is, and I don’t know. And they turn out to be mine. But it’s a sort of unconscious cleansing mechanism, because if everything I’ve written were present in my mind, I’d stop writing. After publishing my Collected Stories and myCollected Poems I had a bout of depression because I wanted to write those texts again in the exact same way. Like the Borges story about Pierre Menard. I wanted to recover lost time, but I realized that I could not be 25 again.

CB The author cannot have the close relationship with his books that the reader can. As a reader, if you adore a book, you can always return to it, but as an author, you can’t. The books one writes are sealed. Something you were saying is interesting: you forget the books that you wrote. You are not an author of literary formulas, ever, not even of a formula that you invented yourself.

CPR No. My formula is to never have a characteristic style. Why? Because there comes a moment when Kafka is too Kafkaesque. A very characteristic style is as if you looked through the kaleidoscope of life only from one angle, never turning the lens. Having a personal style—the greatest literary ambition of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th—has never been an ambition of mine. I have to have a great freshness when I write, so I don’t read everything that I’ve written and, above all, I forget the style in which I wrote the last book. I want to have freedom, and I also believe that each story I come up with deserves its own style.

CB And its own form. Now I want us to return for a moment to Montevideo, before going on to Barcelona. This literary world to which you belonged: Felisberto Hernández, Onetti, and Benedetti, your first literary critic. What other writers were there who were significant to you, who were close? Was there a true literary life, a space where people conversed?

CPR I always considered myself a rebel. From the moment I studied comparative literature and began to work in what we call liceos, or high schools—when I was very young, because I had to pay my way through college—I clearly understood that I was not the successor of any Uruguayan writer I had ever read. My influences were diverse, but they didn’t necessarily come from Uruguayan literature. Let’s see, I greatly admired Felisberto Hernández—I still do—who seemed exceptional to me, though when I started reading him no one else read him. I began to write when the Latin American Boom had not yet become all that it would. Most of the books that later became bestsellers had been published earlier to little acclaim. Borges’s first book only sold 23 copies, I believe.

CB But did you meet Ángel Rama, for example?

CPR Yes, of course. I wanted to mention him to you because Ángel Rama was so decisive for my literary career. He directed a press called Arca. He organized a contest for writers under 30—I was 22 or 23—which I won with a book titled Los museos abandonados (Abandoned museums). I had a very cordial but distant relationship with him. I think he was responsible for my being called, affectionately, “La Rimbaudcita.” Funny, because Rimbaud’s poetry isn’t my favorite—it seems an adolescent offshoot to me. The nickname must have come more from my rebellious and iconoclastic personality than my writing, though maybe it was both. Though Los museos abandonados was only my second book of fiction, he praised its originality and the complexity of its style and structure. He thought it was unclassifiable because it took the conflict between life and culture—the death drive, that is—to an extreme. It was something very Freudian that I wouldn’t have been able to develop in an essay, though I was able to represent it through the subject matter and style of a novel. Rama also thought I was unique because there weren’t any other comparable female writers around at the time. The Latin American Boom included no women.

CB I second Ángel Rama’s opinion that you are unclassifiable, but I believe that one of Montevideo’s undeniable virtues is that it has produced exceptional women authors (luckily not “feminine” authors, in the prejudicial sense of the word). They have no relationship with your work, but they do share your city. Marosa di Giorgio is exceptional, although she seemed to always write the same book, her Los papeles salvajes (Savage papers). There’s Ida Vitale, an extraordinary poet. And Armonía Somers with her Un retrato para Dickens (A portrait for Dickens).

CPR I agree. Uruguay has always produced exceptional women. The fact that the feminist movement began very early in Uruguay contributed to this. Already my mother’s generation was made up of women who enjoyed working and preferred to be single mothers, for instance, since they detested marriage and domestic chores.

CB Delmira Agustini?

CPR The figure of Delmira Agustini is complex because she was a young lady from the middle class with Modernista aspirations—

CB A little girl at home, a vampire in her imagination—

CPR The little girl who played the piano and did all the things the middle class did, but who had a gift, the gift of poetry, and who admired the Modernista poets, who were flattered.

CB Rubén Darío.

CPR Exactly. But then, of course, she went and married a businessman, someone who didn’t share her poetic interests, right? And she had such bad luck! She felt a true physical attraction to the man she married, but after two months of marriage, she returned to her parents’ house with an admirable statement: “Marriage is a vulgarity.” But then she began arranging to see her husband in a bordello. In other words, she went from wife to lover. After they divorced, they kept seeing each other. He shot her dead in a brothel. Perhaps Delmira’s insurmountable contradiction was that she never followed the “perverse path” of a liberated woman. She was caught in between the petite bourgeois and the bohemian life. You could say that she tried to fulfill her traditional role as a woman, and it went wrong. It turned out terribly! Poor woman.

Then there’s María Eugenia Vaz Ferreira. She also had to suffer the consequences of being a woman, and a “strange” one, because she never married, never had children, she wrote poetry, and had a philosopher brother who had her locked up in a mental institution. During this generation that began at the start of the century, women broke with traditional roles, but the definitive break, I’d say, happened with my generation. Our options are not only—

CB Staying at home or joining a convent, for example.

CPR There were other kinds of options, even political ones.

CB Your generation, actually, is one devoted to both intellectual and political activities.

CPR Yes, of course. I belong to the ’68 generation and I continue to advocate for the values it promoted then: sexual freedom, unisex culture, the alliance between workers and students, the antiauthoritarian rebellion, the predominance of the imagination ...

CB You reaped the benefits of the great feminist revolution—

CPR Precisely. What happened is that the second wave of feminism (from the US and Europe) was swallowed up by conventional militancy. The development of feminism, which already existed in Uruguay, suffered setbacks because they told us the story that by participating in guerilla movements, or participating in the far left, we women could attain levels of power we hadn’t yet reached. The only thing we got was stronger repression against women than against men. Many men were imprisoned; women were too, but they were always raped as well. In other words, repression exacerbated the prevailing machismo in Uruguay.

CB Yes, the rapes ...

CPR The military beat men, for sure, but they beat and raped the women. That’s when we women learned that there wasn’t equality anywhere. Besides, inside leftist parties, power relationships are still highly structured. The feminist revolution has very little to do with the leftist revolutions of Latin America. They proposed a different power structure, but one in which a hierarchical relationship of power is still established between the two sexes. It’s trading one type of male military for another. I’ve come across former Tupamara guerrilla women in exile, who after serious consideration, crossed over and became militant feminists, which made them feel more complete and respected, less undermined.

CB Let’s move on from Montevideo, which you were forced to leave, not out of choice, but to save your own skin, knowing that the next female victim, very probably, could be you. And you arrived in Barcelona with almost nothing.

CPR Don’t forget that the first book that talked about the guerilla movements in Uruguay was my Libro de mis primos (My cousins’ book). And what’s more, in the first edition of the Los museos abandonados, the dedication, which I later corrected, was for the guerilla. The book deals with the main political conflicts of the guerrilla—their bourgeois origins, their hatred for intellectuals, their humiliation of women. Cortázar told me that after reading it he had to dump the first version of his novel A Manual for Manuel—there were a lot of similarities between our books. When I wrote the book we hadn’t met yet. Those issues were floating in the air among the ’68 generation—they were a part of people’s daily lives in places as diverse as Paris, La Habana, or Montevideo.

CB What did you do with your political activism in Barcelona?

CPR The only way to counteract the guilt I felt for having saved my own skin—because I felt very guilty for having abandoned my students, my comrades, the political prisoners—was to commit myself to the fight against dictatorships, the Uruguayan and Franco’s. I followed my friends’ reasoning to a T: “You are more valuable outside of Uruguay than in a grave or in jail.” It was very difficult for me to accept this, because I felt a great solidarity, a great responsibility for my students.

CB So you arrived in Franco’s Barcelona.

CPR Yes, and the first thing I did was to connect with the anti-Franco resistance. I began to work from Barcelona on two political fronts: against Francoism and also to inform people about the political situation in Uruguay, a little-known country whose dictator wasn’t a big name like Videla or Pinochet.

CB Which resulted in their throwing you out in 1974.

CPR They threw me out and I had to go into exile in Paris.

CB How long did this second exile last?

CPR This second exile lasted some nine months. It wasn’t only exile; the problem was that the dictatorship had revoked my citizenship, and then I had no documents. I was, in fact, stateless and clandestine in France, which put me in a state of acute anxiety.

CB And how does this astonishing story find you obtaining Spanish citizenship?

CPR I appealed to the brotherliness of my Communist comrades in Spain, and I found a husband. We were brave, because only the church could marry people, and divorce didn’t exist. I entered Spain secretly, and I found a leftist priest to marry us, and obtained Spanish citizenship. Luckily, my husband was gay.

CB There’s an anecdote you tell about La última noche de Dostoievski (Dostoevsky’s last night): the publishers offered you a juicy prize, worth a lot of money, if you made changes to the book, which you refused to—

CPR That’s why I rent and don’t own a house—

CB Let’s talk about the prize that your Dostoievski didn’t win. Why was it so important to you to not make those changes?

CPR Because I was still relatively young and I thought that I alone could take down the market. (laughter) What we are talking about must have taken place 15 years ago. I had just won a prize, the City of Barcelona Poetry Prize. My literary agent knew that I was writing La última noche de Dostoievski. He called me and said, “Look, people are talking a lot about your prize, and a great publishing house called to tell me that they have a prize for a novel.” He asked me, “Did you finish the novel?” “Yes, I just finished it.” “We have a meeting with them.” I gave them the novel, and 15 days later they called me, got out their checkbook like nouveau riches and said, “We will give you the prize money right now, in advance, if you agree to make some changes because, of course, as it is a lot of money, we will have to sell many copies and we need the novel to be more commercial.” And I felt profoundly offended. Above all, because the person telling me this, the press’s director, was also a writer. And so I told him, “There is a mix-up here. I did not submit my book for this prize. If you want to give it to me, go ahead, but the novel stays just as it is. This was not some failed attempt. I didn’t mistakenly write this novel wanting to write something else. No. I wanted to write this one.”

CB What changes did he want made?

CPR He invoked the Anglo editor-figure who tells the writer how his novel must go. I told him, “In the first place, you are not Anglo. I’m not either. And, in the second place, I would tell the Anglo editor the same thing I’m telling you. I write my books myself. The editor edits them. The editor is the editor, but I am the writer.”

CB Was it a structural change? A significant or radical one?

CPR It implied not only changing the order of certain chapters, but also adding others to show the gambling addiction of the character a little more, and to make it attractive, although the character is actually in crisis and wants to stop gambling. He also wanted the love story, which is insignificant and only serves as illustration, to expand and be included from the beginning. In my opinion, the psychoanalytic sessions are the important parts of the novel: their main value is to transmit to the reader all the ambiguity with which the relationship with the therapist evolves. Through psychoanalysis the character discovers his true desire. So I told him, “You want a different novel. Give the prize to a different book, not this one.” It was grotesque, in fact.

CB Would you do the same thing now?

CPR I don’t ask myself these things now because I am so disillusioned with the literary world, and so disillusioned with the capitalist ways of the world that I’d rather not talk about this. The word disillusioned is a misnomer: I never had any illusions about the market or commercial literature. Actually, do you know what I would do now?

CB What would you do?

CPR I’d tell him, “Look, write it yourself, all right? Write it yourself, and I’ll sign it.”

CB It’s one thing to be disillusioned with the true literary world, and quite another to be disillusioned with the business of books and the little cliques of writers and editors.

CPR I am disillusioned with the degree to which we writers have accepted this transformation of the literary world. The degree to which we have accepted that the goal is to have our own flat, vacations in Hawaii, a brand-new car and appear on television. The referents have changed: it’s like there’s been a general desertion. Now, what the young 30-year-old wants is to write a commercial novel, but the worse thing is that the 60-year-olds want the same thing, too! Everyone wants to make money off literature. I, for example, have had another profession my entire life. I’ve translated, done lots of journalism. Unfortunately, I couldn’t teach here in Barcelona but occasionally. If my degree could have been validated, I would earn my living differently. And then my literature would have no ties to money, right? Because on the other hand, of course, I feel completely incapable of writing a commercial novel.

CB What you seem to be very angry about, and justly so, is the idea of literature as kind of bemusement. And not literature as a challenge, and as an existential wager—

CPR As a form of knowledge.

CB I’m not sure about that.

CPR Literature is a form of knowledge, though its subject matter—feelings, emotions, conflicts—only allows us to access it from a subjective standpoint.

CB It’s also a form of ignorance. I’m thinking of Elena Garro again: she was crazy as a loon, and she is anything but an exemplary figure, but her literary world shines light into those dark areas of life that one can never comprehend.

CPR Crazy people tend to have lots of talent. It must be a sort of compensation.

CB Literature as a space of indispensable uselessness, that of the work of art. I detest idiocy. I detest what people seem to want to do: to sugarcoat things, to deceive, to give false answers. Literature is uncomfortable, and so is good film. And what is most uncomfortable, for me, is what I find most fun and fascinating.

CPR There you have it! I believe that knowledge is uncomfortable, and when I want to amuse myself, I play games on the Internet. I don’t amuse myself with music, movies, or paintings. When it comes to those things, I actually suffer. But suffering is also a type of knowledge. A biology book can seem very entertaining to me. I don’t ask that it be well written; I do ask that it provide information. I always demand that literature be written well, because that’s what pertains to literature, correct?

CB Although to write well is not something you can imitate. What I call style is the unique and distinctive voice that upholds the author. You have that, Cristina. Not many people do, but it’s something that I’d almost say can’t be acquired. There’s that extraordinary story by Felisberto Hernández, your compatriot, in which he doesn’t explain, or he does explain, or he gives a false explanation of how he writes stories.

CPR Yes. Yes, I know it.

CB The story is born, or it isn’t born; it’s spontaneous, but it’s not spontaneous. It’s this complex thing, which is the creation of a literary text. And it’s also very simple, right? But there’s a quality that poetry, novels, theater, and essays require and that is authenticity.

CPR Luckily, there still are books in which this idea of entertainment is secondary. Entertainment gets a lot of press because it translates well into images. A great poem cannot be converted into an image. I believe that is what defines literariness: it’s separate from the world of images. A story by Kafka cannot easily be made into images, although they tried it with The Trial … In any case, there still are writers who think that the number of books sold means nothing. But it is true, too, that we are legally unprotected, and we don’t have pensions, and we don’t have social security. We are very vulnerable when facing an industry that turns everything into a sales product.

CB Without a doubt. And you’re in Spain. You have dual citizenship, and at least now you have the protection of the state. But imagine what it’s like in the case of Latin American authors!

CPR In Uruguay, they informed me recently that parliament has just passed a proposal to give pensions to writers. Which would be a step beyond what Spain has done.

CB Wonderful! In Mexico, the big problem is not the growth of the publishing industry, like in Spain—because we still have very few readers; it’s an illiterate country—but rather the relationship between writers and the state. The state is very generous: writers live off of it, and this, of course, corrupts the literary world.

CPR Yes, exactly. That happens a lot here in Catalonia, with culture subsidized in Catalan—

CB Why don’t you speak Catalan? I’m sorry; do you mind answering this question? I’ve know you’ve had trouble because you speak in Spanish on Catalunya Ràdio.

CPR Because I have no ear for any language that is not Spanish. I am a good reader of other languages. I translate from the French, but my French is awful; similarly my Italian and Portuguese. I read Catalan, but I get embarrassed when I speak it. I have a good ear for listening, but a very bad ear for reproducing sounds. Besides, Catalonia—this region, country, or whatever you want to call it—is officially bilingual! I don’t demand that people speak Spanish. Let them speak their language; I understand them and answer in mine. It seemed to me to be a model of coexistence—an almost perfect one, I might add—don’t you think? They can go ahead and interview me on Catalan radio and ask me questions in perfect Catalan—

CB And you’ll answer in perfect Spanish.

CPR I completely understand that there might be people who want a society in which only Catalan is spoken, but I believe that it would be a loss. I don’t understand how in the name of Catalan patriotism, they can exclude a great number of writers, who themselves are Catalan, but who have written wonderfully in Spanish: Mendoza, Juan Marsé, Ana María Matute, Jaime Gil de Biedma ...

CB We are getting into a different kind of discussion that perhaps you would prefer to avoid. But the truth is, at this stage in life, patriotism of any stripes is undesirable.

CPR I completely agree. But, if I tell you this, it’s because I put myself in the place of people who love their homeland. In other words, here, when they ask me, “What are you more, Spanish or Uruguayan?” I say, “I am a citizen of the world.” In any part of the world, I defend the same things. I lived in Berlin where I defended the same things. When I arrived here, I fought against Franco, just like I would have fought for Allende, if I had been in Chile. But that doesn’t mean that all countries are the same to me. The ones I feel a kinship with are those in which justice, and human and animal rights are defended. That’s the true homeland.

CB In my case, I don’t have the slightest doubt that I am Mexican because that was my childhood, but that does not make me a staunch defender of “Mexicanness.” Patriotism always excludes people. In the case of Mexico, those who are excluded from the nation’s project are a fundamental part of it: the indigenous peoples. This disturbs me. And now I live in New York, where 30 percent of the people who live in this city speak Spanish; I live here because I feel it is a city that is part of the world.

CPR There is nothing less North American than New York.

CB I want to be at the limit. I want to inhabit distance, which, by the way, I believe to be the writer’s position. In one of your poems you speak about the “exact distance.” “In love and in boxing, everything is a question of distance—”

CPR Yes, exactly.

CB “If you get too close, I get excited, I get scared, I get bewildered, I say silly things, I start to tremble, but if you’re far away, I get sad, I stay up all night, and I write poems.”

Translated from the Spanish by Sarah Pollack.

—Carmen Boullosa has published 14 novels, most recently La virgen y el violín with Editorial Siruela in Madrid. They’re Cows, We’re Pigs; Leaving Tabasco; and Cleopatra Dismounts have been published in English translation by Grove Press. A sample of her translated poetry appears in the anthology Reversible Monuments: Contemporary Mexican Poetry. She received the Xavier Villaurrutia Prize in Mexico, the Anna Seghers and the Liberaturpreis in Germany, and, most recently, the Café Gijón Prize in Madrid. She’s Distinguished Lecturer at City College, CUNY, and lives in Brooklyn.

FICCIONES

Casa de citas / Cristina Peri Rossi / Julio Cortázar

Casa de citas / Cristiana Peri Rossi / Fetichistas

Casa de citas / Cristina Peri Rossi / Las mujeres casadas

Casa de citas / Cristiana Peri Rossi / Fetichistas

Casa de citas / Cristina Peri Rossi / Las mujeres casadas

DE OTROS MUNDOS

Silvia Hernando / Cuéntame qué cuento leer

Cristina Peri Rossi / Julio Cortázar

Cristina Peri Rossi / Cortázar murió de sida

Cristina Peri Rossi / Julio Cortázar

Cristina Peri Rossi / Cortázar murió de sida

Poemas

Cristina Peri Rossi / Tus senos

Cristina Peri Rossi / Oración

Cristina Peri Rossi / Amor contrariado

Cristina Peri Rossi / Epitafios

Cristina Peri Rossi / De aquí a la eternidad

Cristina Peri Rossi / Tres poemas

Cristina Peri Rossi / Viacrucis

Cuentos

Cristina Peri Rossi / Oración

Cristina Peri Rossi / Amor contrariado

Cristina Peri Rossi / Epitafios

Cristina Peri Rossi / De aquí a la eternidad

Cristina Peri Rossi / Tres poemas

Cristina Peri Rossi / Viacrucis

Cuentos

MESTER DE BREVERÍA

Cristina Peri Rossi / Lavorare stanca

Cristina Peri Rossi / Lavorare stanca

DRAGON

No comments:

Post a Comment