|

| Paul Bowles in Tanger |

'Where do I think best? In bed' – authors reveal their dream retreats

A hotel on the Moray Firth estuary; an adrenaline-filled auction room in west London; an ad man’s office in Manhattan on DVD … AL Kennedy, William Boyd and others celebrate their cultural hideouts

by William Boyd, AL Kennedy, Nicola Barker, Joan Bakewell and Daljit Nagra

Friday 29 December 2017

|

| AL Kennedy |

AL Kennedy: My bed

I’m typing this in bed – but more of that later. Writers asked to expatiate on cultural or creative spaces may tend to feel they have to swear they can’t add one word to another without staying in a Tuscan palazzo, or being surrounded by folk musicians from obscure mountain villages and their charmingly artisanal children. (Sort of like Michael Redgrave in The Lady Vanishes only more lifestyley.) This helps advertisers offer you Tuscan holiday packages, or mountain socks made from homespun doghair.

I do feel my soul stand taller when I look at anything by Goya. One painting and out – I hate galleries. Francis Bacon’s “screaming pope” – and out. Or climb those dark winding stairs up high to meet the blue-red, shining amazingness of Sainte-Chapelle’s high gothic windows in Paris. Or I don’t have to go anywhere. If I listen to Otis Redding, or David Bowie, or Elvis Costello, who is there almost every day, or Bob Dylan, or the opening of “Baba O’Riley”, or the first note of Rhapsody in Blue (which Alistair Cooke talked about on Radio 4 in a way I have never forgotten), these are part of the too-many sounds that make me a portable cultural hideout inside my head, behind my eyes, for ever.

Ditto for almost every word I’ve read – that’s what they are for. They fit your synapses with landscapes, timescapes, personalities that never leave. You can close down a gallery or a library, steal the art, blow it up, but killing all the people who walk about guarding places of beauty is harder. Where do I think best, plan, ponder? Bed. It’s warm, cosy, good for the back – it’s where only nice people are allowed to disturb you.

The bed where I’m writing is in a room on an estuary, the Moray Firth. I come here often for the light, the peace, the people. I grew up on the Tay estuary, my bedroom window overlooking it. I live now on the Colne estuary not far from the home Francis Bacon once shared with photographer John Deakin. The walls of my home – it has a bed – are covered with photographs I’ve taken of seas and oceans all over the world. And there’s a James Dodds linocut of boats. I always think of beds as little boats, sending us drifting away.

This bed is in a hotel. I have to find hotels that are places of inspiration and calm because I spend so much time in them for work. I’m lucky. I’m no longer in the early days, scary-dirty hotels. I’m not, like so many, living out of rooms because I’m homeless but not quite on the streets. I’m not trying to raise kids like this. The joys of a non-scary, clean, quiet hotel bed still thrill me, the peace of a neutral anonymous space where I can think and see the sea. Perfect. (Or the Carlyle in New York – not so rural, but it’s the Carlyle.) The Wickaninnish Inn on Vancouver Island, a hotel with beds that look at the sea, at ravens and at bald eagles passing your window. Ideal.

The kindest creative hideaways have my godchildren nearby, or my mother downstairs reading and heckling Love Actually, or put me within reach of my gentleman of choice. The space within kind arms – it is rest and inspiration wherever you are. Love makes us hiding places that are preparations and not prisons, retreats and not fortresses. That’s something for which to be grateful. And then off I go, back to work and there are beds – for writing.

|

| William Boyd |

William Boyd: Christie’s, South Kensington

I arrived to live in London in 1983 and, I confess, immediately became an addict – of art auctions and auction houses. And it is a real addiction, an auction: anticipation, suspense, adrenaline-high, intense endorphin pleasure release (or, inevitably, massive frustration). In the 1980s and 90s I nearly always went to Christie’s second, smaller set of auction rooms on the Old Brompton Road, South Kensington, occasionally venturing further afield – in search of my fix – to the grander rooms at Christie’s King Street, or its rivals, Sotheby’s, Phillips or Bonhams.

Astonishing bargains were to be had at Christie’s South Ken, in those days and over the years I have probably bought dozens of drawings and small paintings, sometimes on a whim. I bought two quite good Augustus John drawings for £90 because nobody else was bidding. But I also acquired, at incredibly reasonable prices, paintings and drawings by Keith Vaughan, Sandra Blow, John Hoyland, Graham Sutherland, Michael Ayrton, Alan Reynolds and many others. Times have changed and prices have risen sharply. The rooms have changed, too: they are much smarter and considerably spruced up – there is now a chic cafe – but, at the time of my regular frequentation, they were somewhat shabby and knocked about. There was nothing daunting about them for the tyro auction-haunter. Entry, of course, was free and you could spend a day there if you wanted.

I’ve said before that auction houses are a tremendous way of looking at art – good, bad and indifferent – and, paradoxically, it’s often the adjacency of the last two categories that allows your appreciation of what’s “good” to mature and develop. I used to pop in to Christie’s South Ken (I didn’t live far away), about once a fortnight and the place became an ever-changing art gallery for me. My acquisitive interests were in 20th-century British painting, but because of the endless, revolving sales, you found, perforce, that you saw everything from old masters to modern European, minor masterpieces and awful tat. And, as you wandered through the rooms, you would take in antique furniture sales, jewellery sales, watch sales, pop memorabilia sales, Persian carpet sales, and so on. Christie’s South Ken was a kind of cultural souk. There was always something to catch your eye and once you’d viewed and made your choice, the build-up to the eventual sale – with its attendant, conflicting pressures of covetousness, hope, budget issues, rivals and risk (other art dealers in the main) – made the place incredibly alluring.

I was often in that section of the Old Brompton Road, anyway. There was a big Waterstones there (now gone, the first ever Waterstones, I believe) and some decent pubs and cafes to loiter in while you waited for your lot number to come up. Also, because of the presence of the Lycée Charles de Gaulle, a block away, the surrounding streets were full of French voices and French shops. A little bit of Paris in southwest London – perfect for a Francophile like me. It felt strangely cosmopolitan.

But it was the auction rooms that drew me back and I now realise I must have looked at thousands of paintings over the years and inevitably my taste and my acumen (such as it is) broadened and changed. You can scrutinise art much more boldly in an auction house than you can in a gallery. You can unhook paintings from the wall, look at the back, hold them inches from your eye. My auction addiction has lessened, somewhat, but even today the siren song of Christie’s South Ken is undiminished. It’s impossible to walk by without going in.

|

| Nicola Barker |

Nicola Barker: St Mary Moorfields, City of London

I wouldn’t call myself a misanthrope exactly (she growls), but one of the main reasons I’ve always loved living by the Thames is how empty the river feels (aside from the occasional sightseeing boat or battleship or tug). All that space, that room, and the glorious slab of empty sky above. You can stride down on to the beach when the tide is low and be completely and utterly alone. You are highly visible, though, seen from the warehouses and flats on the riverfront, which makes you feel safe. I love this sensation. It’s almost like being in a film or starring in a play, knowing that you are seen, are a part of the landscape, a point of interest, and yet feeling this intense sense of recollection and isolation and self-containment.

There are many ways to be comfortably alone in a city. Walking is one. But creating quiet gaps and spaces for myself within a slightly more social context is also something I love to do. My favourite place for this is St Mary Moorfields in the heart of the City. I see each visit there as a kind of metaphorical Thameside-style amble for the soul.

I actually walked past this church for many years and didn’t dare to enter. There is nothing to it from the outside – just some glass doors inbetween a jewellers and a card shop a minute’s walk from the crazy bustle of Liverpool Street station. It’s unobtrusive – hardly there – almost Narnia-esque. You have to walk down a few steps to enter, then pass through another couple of sets of doors, each one taking you down further and further into the ecclesiastical womb.

Once inside it’s a small but pretty space – not remotely claustrophobic – that feels as if it’s semi-submerged in the London sod and loam. The best thing about it – aside from the warmth and the lovely light from the chandeliers and the polished wood and the banks of burning candles – is that everyone is equal here. It is a City church that effortlessly unites the well-heeled gent and the tragically destitute, the traveller and the local, the religious and the sceptic, with no palpable sense of conflict or unease. It is magnificently cosmopolitan. All are welcome. Nobody seems or feels out of place. It is a profoundly dignified, proper, reverential, and, well, yes, loved space.

There are at least three masses said every weekday. I like to attend with the office workers who are skipping lunch. On Fridays a woman with a gorgeous voice sings the psalm.

This church is unusual in that it celebrates what Catholics call “eucharistic adoration” all day. So the “living presence” of Christ (in the form of a wafer) is placed by the priest in a golden monstrance on the altar after morning mass. The eucharist may never be left unaccompanied, so there is always someone there, a volunteer, sitting quietly, companionably, often deep in prayer. During these times the air itself thickens, it seems to shimmer and glow. There is a sense of hush and excitement and reverence.

Just before lunchtime mass the rosary is recited – a strange cacophony of mumbling voices conjoin to repeat the prayer; a delicious maelstrom of different accents working with and against each other. It’s haunting and unearthly and there is no pressure to participate. It doesn’t matter why you are here, there is no compulsion to say or to do, just simply to be, to sit, to exhale, to reflect.

|

| Joan Bakewell |

Joan Bakewell: Church Cottage, Stratford-upon-Avon

Tucked away in a village cul-de-sac in rural Warwickshire is a precious gem known and loved by those who use it – female writers over 40 for whom it was created.

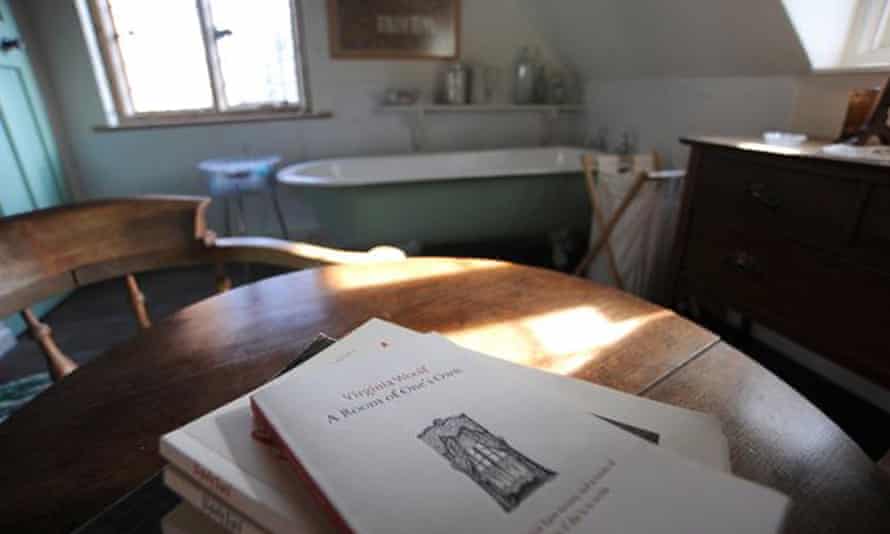

Church Cottage is the brainchild of a remarkable woman, Sarah Hosking. Drawing on Virginia Woolf’s remark that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction”, Sarah has made this tiny cottage into just such a haven: one lower and one upper room, each no more than 15sq ft, bearing all the hallmarks of her country style: pictures, cushions, rugs, an open fire. Here are all the comforts for the focused life: downstairs a living room/kitchen/desk space (wifi, broadband, printer); upstairs a sumptuous double bed and free-standing bath.

Outside, beyond the tiny garden, a path winds through other country gardens, by swathes of cowslips, daisies, violets to the bank of the river Stour where there’s a bench below a yew. Horses appear in the field opposite; I sit there and wait for thoughts to arrive. And words. The cottage overlooks the graveyard of St Helen’s church, where in early summer magnolias shed their petals. The church clock chimes sweetly every hour … its midnight toll is especially comforting. I dream of it when I am not there.

This is where female writers with a book already commissioned come for peace and inspiration. Sarah has extended Woolf’s suggestion to include writers of biography, history, film and television scripts, and poetry, even music. I came here to write my last book, Stop the Clocks, and was so happy that the place wove itself into the text. Others who have sought this heavenly quiet include novelist Salley Vickers, poet Wendy Cope, playwright Timberlake Wertenbaker. But there are many more. The word has spread that this place is special.

The Hosking Houses Trust, set up as a charity and active since 2002, runs the enterprise. Writers can stay for a matter of months or merely weeks. Some – including myself – come several times. It offers not only accommodation but also now carries bursaries of up to £1,000 per calendar month.

The trust works hard to survive: it has enjoyed Arts Council support, has important links with the Royal Shakespeare Company in nearby Stratford-upon-Avon and is developing plans with Coventry University to host artists who deal in words and calligraphy. It is one of those precious unsung enterprises, run by those who love books and writing, who enjoy encouraging creativity and helping those who need space to stop and think away from busy cluttered lives. Many of us have reason to be grateful. The evidence is in our published books that sit on the shelves around the room where they were written.

|

| Daljit Nagra |

Daljit Nagra: The box set

My retreat from the world, after my children have gone to bed, all too often involves the television and box set dramas. Most days of the week, my wife and I will turn to the series that is currently absorbing us. We are always careful not to watch too many episodes in one go. Steady! Perhaps an hour at each sitting is enough to help bring the day to a pinnacle, to an illuminating close.

We have probably been through the dramas familiar to many. We started off a few years ago and tentatively with a few episodes of The Sopranos, not expecting to reach to the end of even a season, yet within a few months we had worked our way through all six seasons – that’s 86 episodes, with each episode lasting nearly an hour. That’s some retreat, for sure! We then retreated to The West Wing, The Wire, Six Feet Under, Breaking Bad, Mad Men, Nordic dramas and along the way we’ve watched each season of British dramas such as Happy Valley and Line of Duty.

I’m not sure if I’d watch these dramas without my wife. Watching a series together feels like a heightening of marriage, it’s something that carries us along together, in a shared affection for the highs and lows of the characters in whom we’ve invested our evenings. Each episode is a communion and our subsequent discussion of the events is a ritual that extends the pleasure of the retreat as we enter our personal bubble of thoughts and opinions about the character dynamics, themes or perhaps the personal memories an incident has resurrected for us.

A box set is an affection generator. It gives us a sojourn and shared thrill each evening. I like it when we’ve watched several episodes and are firmly rooted in the series; we often find ourselves indulging in a complex analysis, like a pair of would-be armchair pundits, while in the park by the swings, or in the supermarket. So the evening retreat is an escape yet it’s also one of several ways we continually recharge the literary life of the marriage so we are enriched with shared memories. There is deep love in this, in this being in the bosom of a box set.

My retreat is qualm-laden. It causes me tension as I reach for the remote control to set up the latest episode. I am aware my time on Earth is passing, that I should be reading a book of poems or some essays to improve my poetry skills, to help me address the mysteries that puzzle me from day to day. Yet instead I’ll watch television often with a glass of Gavi. I tell myself, I’ve been reading all day. Besides, reading is a withdrawal from the other, a too-personal retreat and in my evening with my wife, I should share my life with her and not another book. And box sets in themselves are not so bad.

To alleviate my guilt about my lack of evening reading, my wife and I always enjoy watching highly sophisticated dramas. Dramas that will stretch our knowledge and intelligence because they have been written by a team of writers who have taken each script through several rounds of edits. And as we have fairly young children and no family to help out nearby, we have temporarily withdrawn from the nocturnal life of theatres and cinemas. Why go out to the world when the world has come to us?

THE GUARDIAN

No comments:

Post a Comment