|

|

© Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2017

|

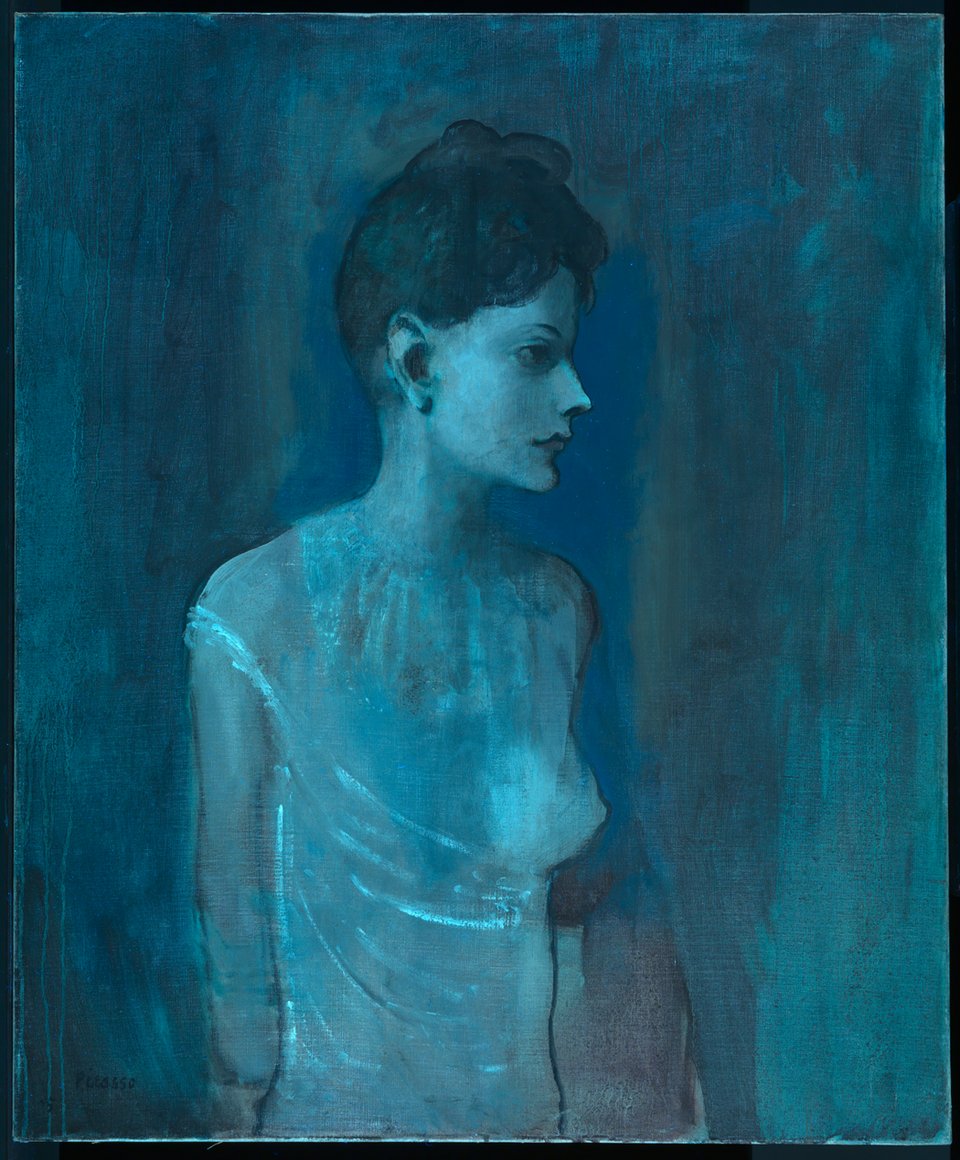

Girl in a Chemise c.1905 by Pablo Picasso

Annette King, Joyce H. Townsend and Bronwyn Ormsby

Tate Papers No 28

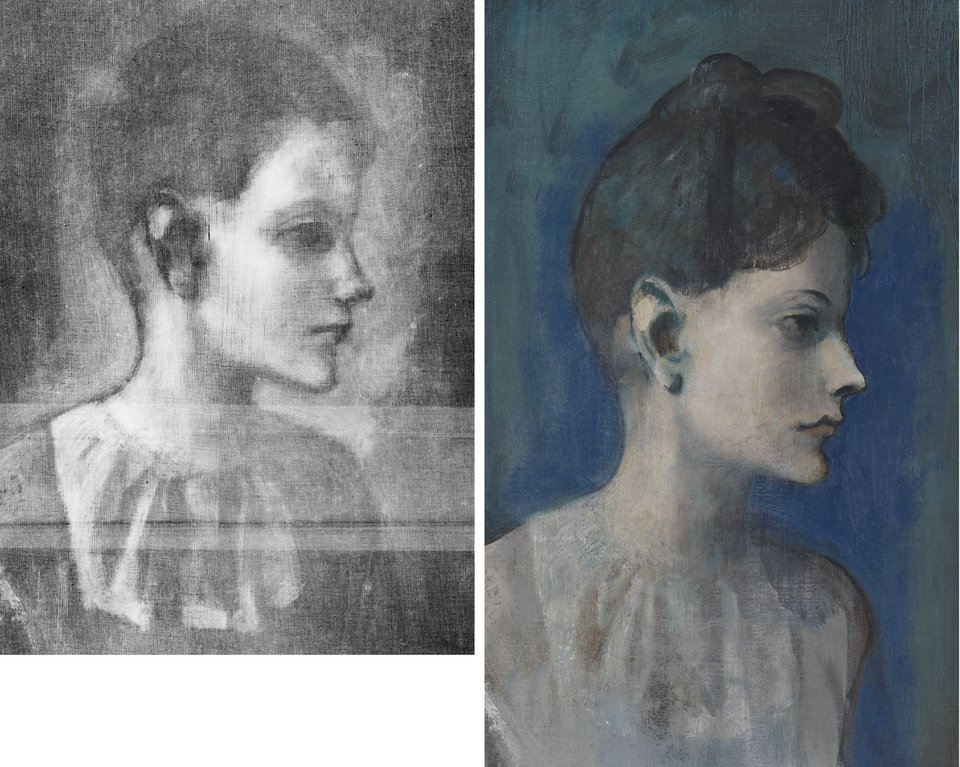

Picasso transformed an earlier painting of a boy to create this profile of a slender young woman. This paper uses X-radiography and infrared imaging to look beneath the surface of the painting and unravel the way in which Picasso transformed the male figure into a female figure with a few deft brushstrokes. The contemporary Parisian context and the identity of the sitter are discussed, as well as the skill and delicacy of Picasso’s early painting techniques

Girl in a Chemise 1905 (fig.1) marks a moment of transition in Picasso’s early work, from the dark misery of the ‘blue period’ to the reintroduction of colour and lightening of subject matter known as the ‘rose period’. Picasso painted this work in Paris at the beginning of a new phase in his life, with new loves and new artistic influences. He arrived in Paris from Barcelona with his Catalan friend Sébastia Junyer-Vidal in 1904. Junyer-Vidal had announced Picasso’s intention to return to Paris in an article on 24 March 1904 and only two weeks later, on 11 and 12 April, the same paper reported that ‘The artists Messrs. Sebastia Junyer-Vidal and Pablo Ruiz Picasso are leaving on today’s express for Paris, where they propose to hold an exhibition of their latest works’.1 Picasso settled into a studio recently vacated by Paco Durrio at 13 Rue Ravignan. ‘The building was called the Bateau Lavoir because it looked like a Seine washing barge (perched on a hill in Montmartre) and also because the floorboards in the old, ramshackle hallways creaked like a boat’.2 The Bateau Lavoir may have been ramshackle but it was a hub of artistic activity, populated by young artists and models from all over Europe, including Spanish compatriots.

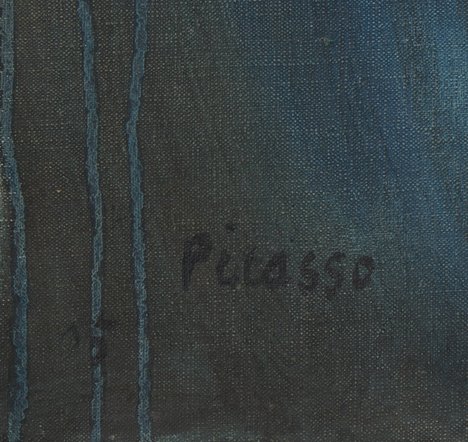

The painting is signed and dated ‘Picasso ’05’ in the lower-left corner of the canvas. However, the date was questioned by Picasso’s dealer Daniel H. Kahnweiler in a letter to the Tate Gallery in 1953.3 He wrote: ‘FEMME EN CHEMISE: This picture, on its original photograph … is dated autumn 1904. If it has been dated later 05, this date is a mistake’.4 The date of execution is therefore unclear, but it is generally accepted that it was begun in 1904, while acknowledging that the signature and date could have been added by Picasso when the painting was finally finished in 1905, although not necessarily at the same time – a point investigated later in this article. The date is significant when considering the identity of the subject, a young girl. It is possible that the girl is a sort of hybrid figure, combining features from various models painted by Picasso at the time. However, a tentative identification has been made by Picasso scholars. Kahnweiler dismissed the idea that the girl was Fernande Olivier in another letter to Tate in 1954, but declined to speculate further on her identity, stating only that ‘Picasso did not know Fernande Olivier when he painted this picture. The model was the woman with whom he was living then, before Fernande Olivier. I do not remember her name and I think it would be of no use mentioning it; Picasso, I am sure, would not like it’.5 The subject of the painting is a waif-like young girl, wearing a chemise which has slipped off her left shoulder to reveal a naked breast, accentuating the slenderness of her frame. The girl has dark hair piled up on top of her head, and she has a pale complexion, enhanced by blue shadows, making her appear even more fragile. Biographer Pierre Daix was the first to identify the girl as Madeleine6 – a model and Picasso’s girlfriend from the end of spring 1904 – and Picasso expert John Richardson later took up the identification:

A new face in his work reveals that Picasso had found a new mistress. Madeleine she was called; all we know is that she was a model … she was pretty in a delicate, bird-like way (her nose and forehead formed a straight line). Madeleine’s thick hair, loosely drawn back into a chignon, and her boyishly lean body recurs in a number of works done over the next six to nine months – works that mirror the blurring of the Blue into the Rose period.7

According to Richardson, Madeleine found that she was pregnant in the summer of 1904 and with Picasso’s approval she had an abortion.8 One of the reasons Picasso sanctioned this may have been that he was beginning ‘an on-off affair with another model – one who lived conveniently close: in the Bateau Lavoir. This girl went under many different names but is best known as Fernande Olivier’.9 It seems that the two affairs overlapped, and tragically for Madeleine the only surviving written memoire is by Fernande, who writes her out of Picasso’s history at the time. As Richardson points out, ‘Fernande’s memoires omit any mention of her rival … Although Picasso first met Fernande in August 1904, it is Madeleine’s skinny beauty that continues to haunt the work – at least until Spring 1905’.10 Kahnweiler’s assertion that Picasso did not know Fernande at the time is not accurate if the above account is true, although he is probably correct in suggesting that Picasso would not have enjoyed the speculation.

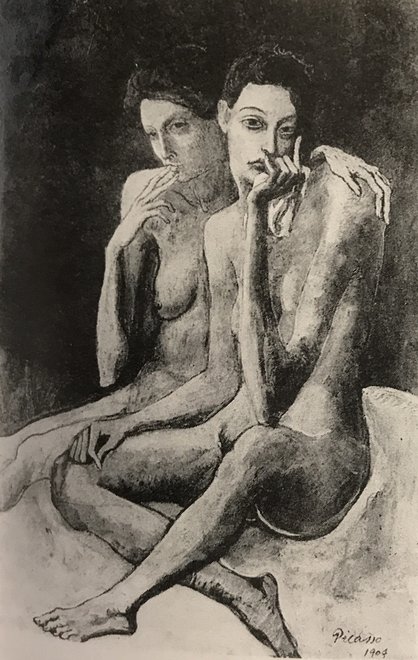

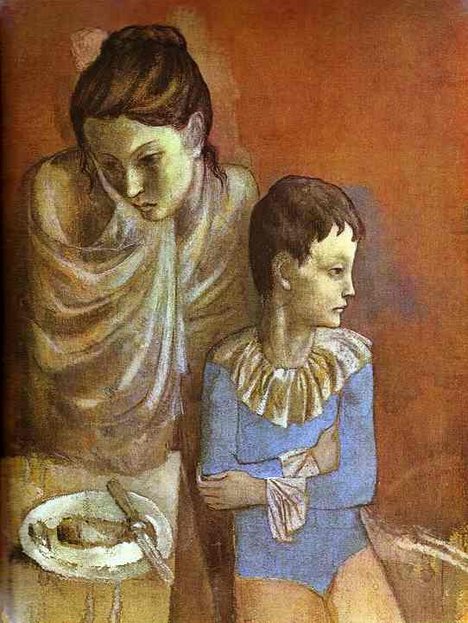

Images of a mother and child also appear in 1904 and early 1905 with a face that resembles that of Madeleine. A black crayon drawing, Mother and Child 1904 and Harlequin’s Family with an Ape 1905 (fig.2) both portray a girl with similar features to the subject of Girl in a Chemise.11 It was mooted by Richardson that these paintings coincide with when Madeleine would have given birth, and that they represent a complicated mixture of emotions in a Picasso torn between guilt at the abortion and a longing for children.12 Madeleine also appears nude in a painting called Friends 1904 (fig.3), which has rather more sexual and lesbian overtones (the original French title ‘Les Amies’ takes the feminine form of the noun). Although there are other models who feature in Picasso’s work from this time, and some of these images may contain a certain amount of artistic license, some of Madeleine’s features are quite distinctive and she seemed to represent the focus of some of Picasso’s complex fantasies.13

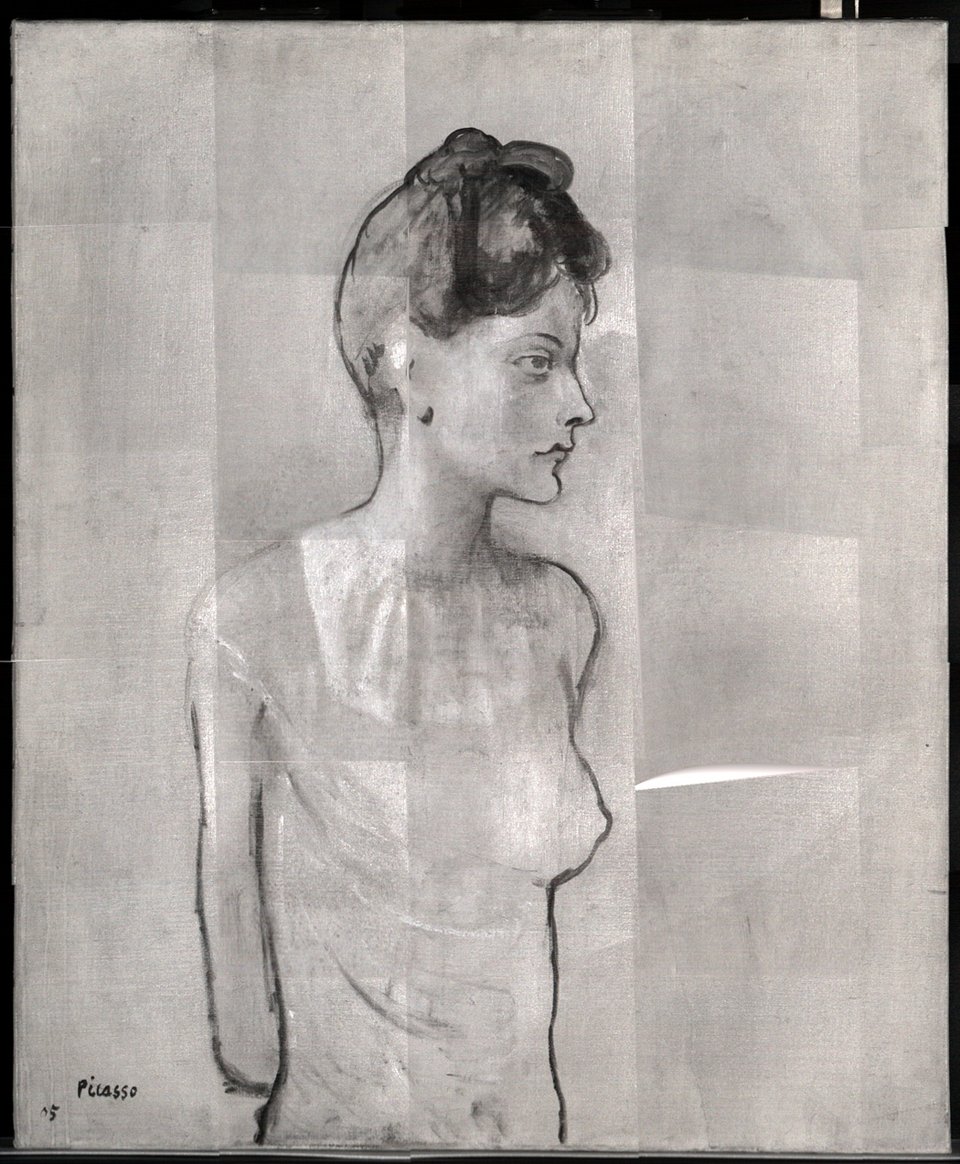

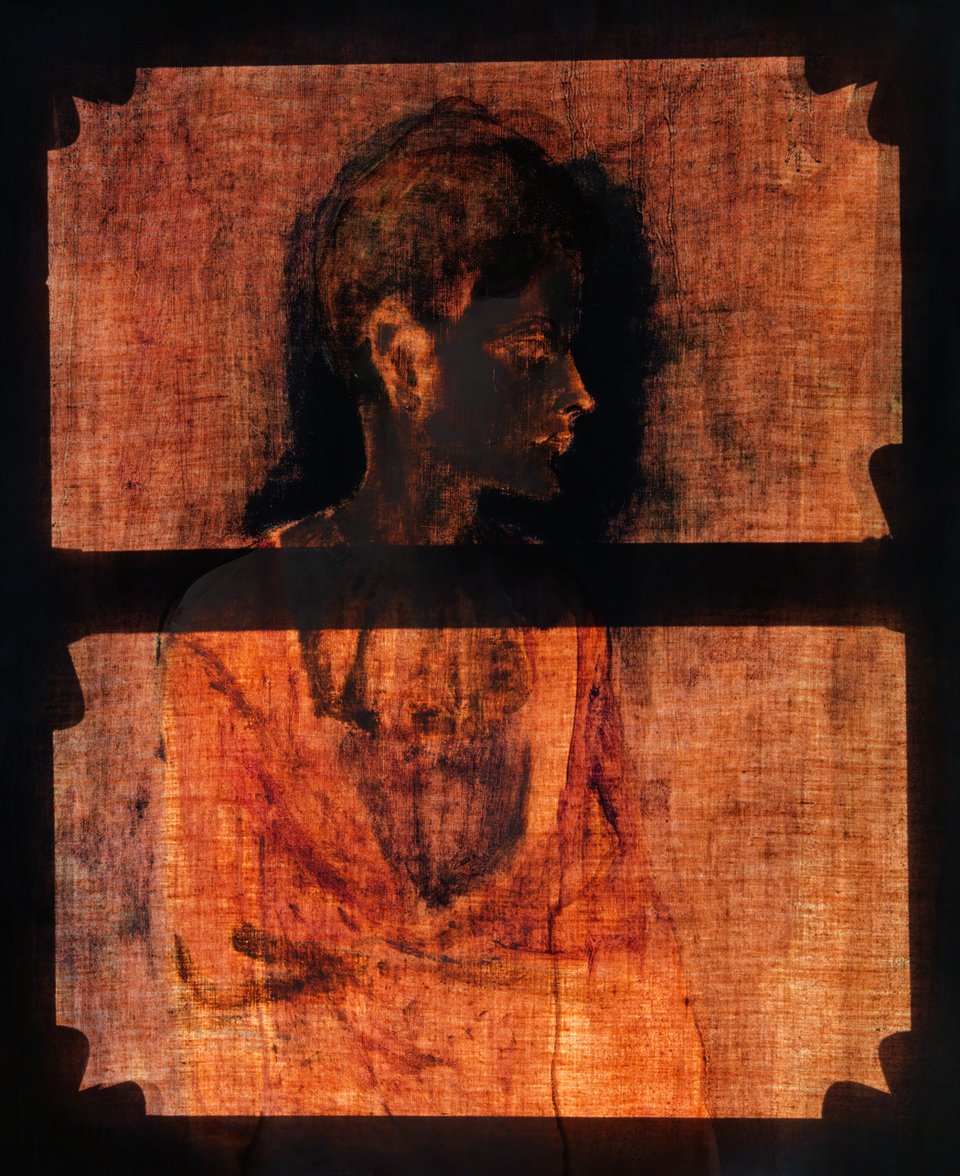

As already indicated, Girl in a Chemise marks the beginning of a slight softening of Picasso’s palette and a move away from the abject subject matter of his ‘blue period’ in Barcelona. Although it is undoubtedly predominantly blue, there are hints of warmer rose and brown colours in the background, and in the flesh and lips of the figure. X-radiography (fig.4) reveals that beneath the female figure there is a painting of a young boy with a floppy collar, which today appears to be barely disguised by Picasso in the final painting, although the natural tendency for oil-based paint to grow more transparent over time means we should be wary of assuming that it was always so easy to see the underlying image. The subject matter of the saltimbanque (travelling entertainer) featured heavily in Picasso’s work of this period, and it seems that this work was originally conceived as a portrait of a young boy, possibly one of a band of itinerant players, dressed in a costume which may be associated with that of a Pierrot figure.

The androgenous nature of the subject in this painting becomes heightened by the discovery that the figure was initially a boy. The blurring of gender becomes a physical reality in paint. The figure herself is undoubtedly intended to be female, the naked breast an obvious identifying feature, yet she retains a boyish feel. Picasso does not completely obliterate the Pierrot underneath. The girl’s upper chest, although supposedly nude, includes substantial traces of what looks like a ruff or floppy collar, partially concealed beneath the flesh paint, almost more clearly visible than the translucent chemise itself, defined by a few impasto white lines. The sparsity of paint makes the transformation all the more remarkable. It is not known when Picasso transformed the painting from a young boy to a young woman, but it is possible that it happened quickly and that the painting was finished by spring 1905, when he may have added the date.

The painting also marks a transitional period when Picasso was experimenting with different media, including drawing, engraving and painting with gouache, while also stretching the capabilities of oil paint to its limits. All of these materials and the techniques they demanded seem to have had an influence on the methods of paint application deployed by Picasso in this work. This study will examine the making of Girl in a Chemise and the relationship between the young saltimbanque figure and that of the girl. The masterful way in which Picasso has transformed the male subject into a female portrait with a minimum of paint will also be explored.

|

Fig.5

Girl in a Chemise c.1905 under oblique light, revealing the face of the boy

Photo © Tate

|

The earlier painting

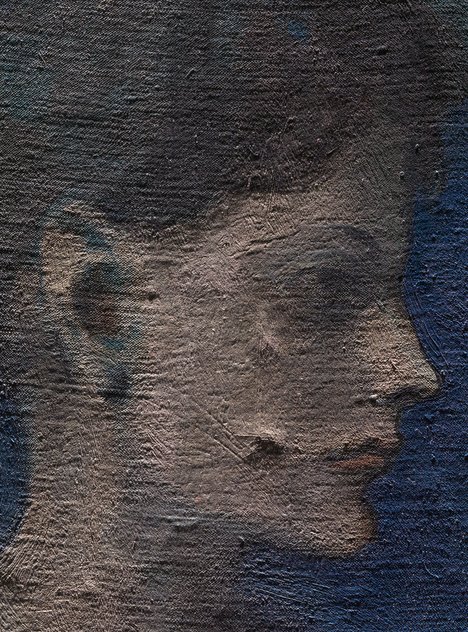

In the X-radiograph of Girl in a Chemise (fig.4) a young boy with a pleated white collar, short cropped hair and possibly a skull cap is clearly visible. His skinny body is more or less facing the viewer while his face is in profile. He appears to have his proper right arm bent almost horizontally and the left arm folded across his body, his left hand cradling the elbow of the right arm. There is the ghost of a cuff visible. The hand is just visible in the final painting in the arm of the girl as blue horizontal lines (see fig.1). The transformation from male to female is remarkable in both its simplicity and effectiveness. A minimum of paint was used to transform the profile from male to female. It is fascinating that in certain somewhat oblique lighting (fig.5) it is the boy’s face and hair that are visible rather than those of the girl.

Art historians have argued that Picasso chose to paint itinerant performers because they were a subject he could make his own, with a French flavour and classical associations, but without being academic.14 Roving circus troupes and acrobats would have been a familiar sight in early twentieth-century Paris, and would have featured in cartoons and popular media, becoming part of the social consciousness. This form of popular entertainment had its origins in late Renaissance Italy but was taken up and absorbed into the traditions of other countries. In England it became the puppet shows featuring Punch and Judy. In France the dreamy, innocent Pierrot character had been immortalised by artists such as Jean-Antoine Watteau, Honoré Daumier, Paul Cézanne and Edgar Degas.15 The subject of Pierrot, being a specifically French trope, may have appealed to the young Picasso arriving in Paris. Having said that, it seems clear from the image that Picasso was not trying to depict a fictional character but rather an emaciated boy acrobat, dressed in a shabby approximation of a Pierrot costume. Acrobats and street entertainers were often dressed in costumes that referred back to the tradition of the commedia dell’arte, but apart from the floppy collar, the boy looks more like an urchin Picasso might have encountered in the real Paris of 1904 than an idealised character.

This boy does bear similarities with figures in other works by Picasso during this period, and perhaps the closest in pose is the boy in Mother and Child, Acrobats 1904–5 (fig.6). The boy in the X-radiograph (fig.4) is dressed in a slightly narrower white floppy collar with straight vertical edges, unlike the boy in Mother and Child, Acrobats whose collar falls over his shoulders. There is no voluminous white robe typical of a traditional Pierrot in either image, but the X-radiograph possibly hints at a black cap on the boy’s head, suggested by an absence of denser background paint. The roundness of the top of his skull and a slight indentation at the back of the head may suggest a skull cap.

The X-radiograph is intriguing, as apart from the obvious figure of a boy with white collar, there are other faint and indefinable shapes. At the right-hand side of the X-radiograph there is a strange semi-circular line. Beyond the outer curve of the semi-circle the corners of the painting are just dark and featureless. However, within the semi-circle there is a round shape which resembles a head at right angles to the current image. To the left of the boy’s proper right elbow there is a diagonal oblong, which could define the edge of a table. In the upper-left corner, just left of the boy’s head, there is a faint whitish, round shape, which in comparison with Mother and Child, Acrobats, one could interpret as being similar in form to the mother’s head. It could be that Picasso re-used a canvas and scraped it down before painting, or that he experimented with images, and erased earlier designs. Because the paint films are so thin, there is little chance of seeing a defined image beneath.

The stretcher for Girl in a Chemise is a standard 20 figure size – 73 cm x 60 cm – and there is a very faint ‘20’ stamped on the top stretcher member and an ‘F’ on the cross-member – ‘20F’ being the usual connotation for this size. It has expandable mortise and tenon joints and is made of softwood. The black inscription on the central cross-bar proved impossible to read. It appears to be the original stretcher and the painting still has its original attachment.

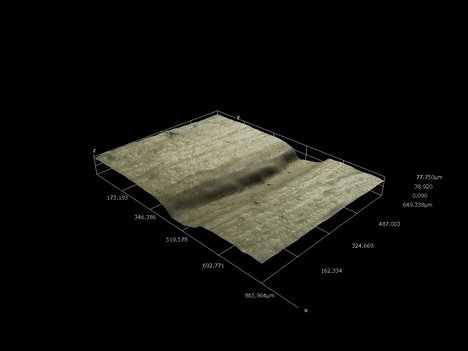

Where the ferrous tacks were inserted into the tacking margins the canvas has stretched slightly (figs.7a–c), creating points of tension and causing characteristic cusping (scallop-shaped distortions) in the canvas support. This cusping is evident in the raking light image (fig.8) where shadows accentuate the undulations in the canvas which correspond to the tacks (this is more obvious at the top and bottom because the lighting is from the top). The canvas was cut very close to the back edge of the stretcher (see fig.7a), likely with a knife since the stretcher bears the scars of a blade in places. In places there are traces of paint which conform to the shape of the tack (see fig.7b). There are additional tack-holes, most likely from an earlier batten frame attached with tacks, since these tacks have not held tension and distorted the canvas while it was being painted.16 There are no visible selvedges,17 and the off-white priming extends all the way to the cut edges, suggesting that it was pre-primed and stretched conventionally, the trimming having occurred after purchase. The canvas is a plainly woven linen canvas, with 25 warp threads per centimetre and 27 for the weft, a very fine piece of fabric, but with no canvas stamps for identifying the colourman who supplied it.

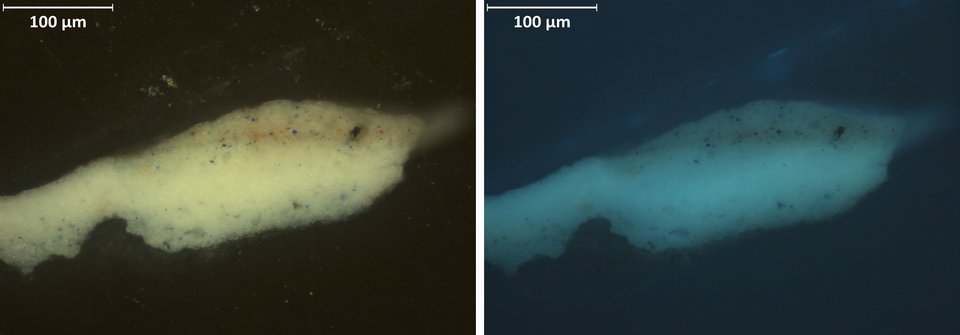

The ground was identified as lead white in drying oil.18 Two layers of off-white ground can be seen in cross-section (fig.9), the lower layer coarser than the upper layer. It is possible that the upper layer, slightly warmer in tone, was applied by Picasso over a commercial ground, since it is not uncommon to find only a single layer of commercial priming on a canvas prepared in France at this date.

From the X-radiograph it was clear that the canvas had been used before: the pre-existing but not identifiable image was rubbed down or scraped before Picasso started to paint the boy. There are no clues in the short-wave infrared (SWIR) image (fig.10) as to what lay beneath the boy. The semi-circular shadow in the lower-right corner is just visible, but there are no other lines or shapes discernible in the blank background. Equally there is not much trace of underdrawing because the washy painted lines outlining the female figure in the upper layers predominate. But in the hair a thin line traversing the skull in a shallow diagonal line, either a thin painted line or done in charcoal or graphite pencil, could delineate the lower edge of a cap. A brushed line around the top of the head is smooth and circular and may define the upper edge of a cap, or just the smooth rounded line of the boy’s close-cropped hair.

Another thin line runs from the proper left shoulder, down through the breast and possibly then lies beneath the black painted line defining the female. This seems to have outlined the boy’s torso, before being transformed into the girl’s profile. The line of the neck seems to have changed, as in the SWIR image, where a more masculine neck with the Adam’s apple lying within the final neckline is discernible. The canvas texture and the washy brushstrokes in the background are both accentuated in the SWIR image.

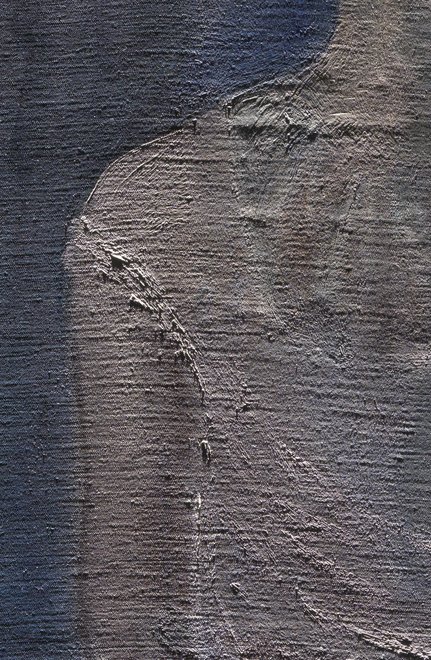

The extreme thinness of the paint layers becomes evident in the transmitted light image (fig.11). The thickest areas of paint application appear dark, and they are concentrated around the head of the figure. The roundness of the boy’s head is visible within the more feathery contours of the girl’s chignon. The eyes, nose, lips and ear have been crafted from very few brushstrokes, leaving much of the shape to be defined by scraped-back underlayers. The collar is thicker along the vertical lines of the folds and again is mostly thin and transparent in transmitted light, despite being so evident in the surface when viewed in normal light. The sharp, straight line running along the right-side of the body is partly a clearly defined block of paint and partly the black line which continues to the base of the painting. The area where the breast has been inserted lies between this extreme straight line on the left and a more flowing diagonal line which creates a sort of triangle from shoulder to base. This seems to have been delineating the boy’s arm, possibly in a more voluminous sleeve. The hand of the arm crossing the body of the boy is clearly visible in transmitted light, although the actual arm is more nebulous. It also seems that the proper right arm which ends at the girl’s hip in the final painting may have been extended within the bottom of the canvas in an earlier experiment, as there is a clear outline. The scraping of the canvas and exposing of the peaks of the canvas threads contributes to the accentuated canvas weave in this image.

The poet Guillaume Apollinaire wrote of this painting that ‘The colour has the flatness of frescoes; the lines are firm’.19 The effect of scraping layers of paint can be seen more readily with a microscope (fig.12). Picasso cut right down to the canvas tops. Art historian Marilyn McCully associates this ‘flatness of frescoes’ with the matteness of gouache, which was a material favoured by Picasso for many of the saltimbanque paintings of this time: ‘Painted in soft tones, the thinly applied gouache tends to fuse the figures with their setting, the empty space of a terrain vague’.20 McCully also describes his thin washes of oil paint as succeeding ‘to create figures whose presence is as ephemeral and evocative as their marginal existence as travelling performers’.21

In Girl in a Chemise Picasso seems to have been experimenting with materials, imitating the flat matteness of gouache with oil paint, working the surface doggedly until he had achieved the desired effect, almost like an aged, painted wall where the years of layered paint had been scrubbed away to reveal all the different colours, in a complex patina of age. Thinning paint with turpentine naturally leads to a matte paint, and here the paint was skilfully thinned to such a degree that it only just forms a coherent paint film.

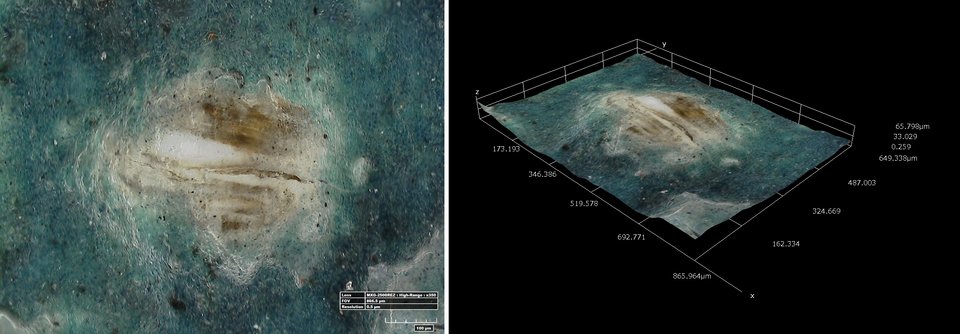

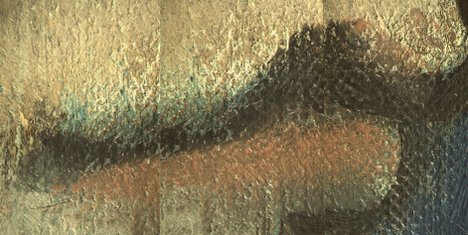

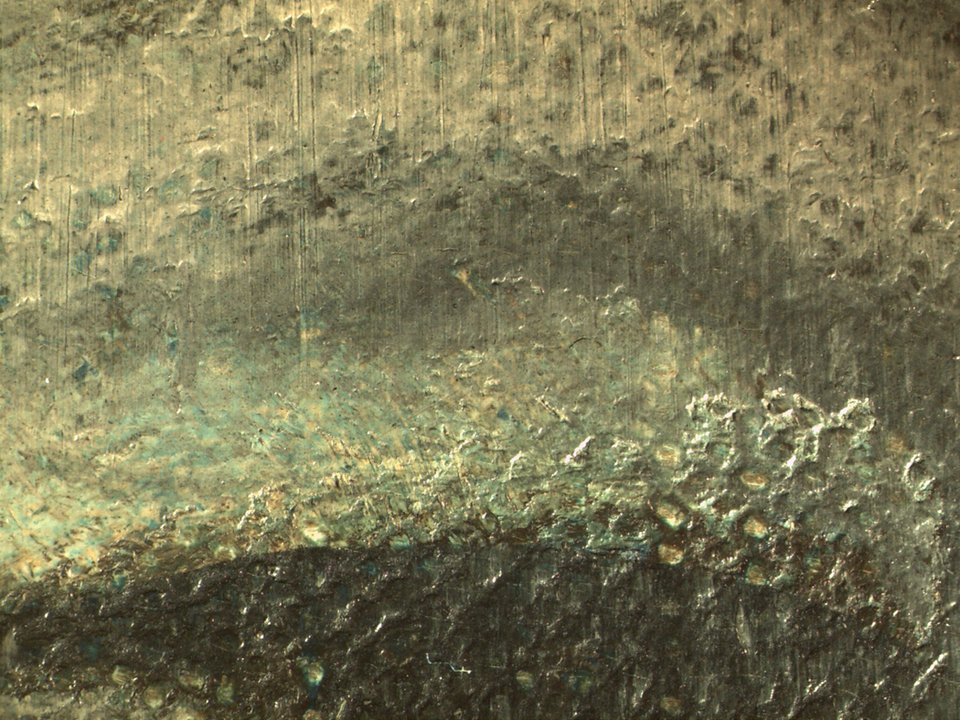

By exposing the layers beneath, Picasso could simultaneously exploit the optical contribution of numerous pigments, albeit on a subtle, microscopic level. In fig.13a the lines of the canvas threads are visible within a halo of white ground, while hints of blue from an earlier layer show through the grey/black of the surface paint creating a lively texture. In fig.13b the canvas fibres are also visible, along with traces of white ground, pink underpaint and washy dark brown paint which has settled in the crevices.

Once the thinly painted, brushy background and the rubbed-down base of the figure had been achieved, Picasso applied further layers to create the final image. In some areas this included thicker layers of oil paint, such as the flesh paint of the face (fig.14). However, not content to let this paint acquire a smooth, flawless surface, Picasso seems to have scored the paint with vertical lines (fig.15).

It is instructive to compare the painted, scored surface with a dry point on copper – Head of a Woman in Profile 1905 (fig.16) – which has been closely associated with Girl in a Chemise and is also thought to be a portrait of Madeleine.22 The likeness is striking, but so are the almost violent striations in the face. Picasso was experimenting with engraving as a source of income at this point in his career, encouraged by fellow artist Julio González who even prepared plates for him. Fernande Olivier described a large print, known as The Frugal Repast, which she also saw in the studio in September 1904: ‘He’s working on an etching showing an emaciated man and woman seated at a table in a wine shop, who convey an intense feeling of misery and alcoholism with terrifying realism’.23 It seems the straight lines and the texture created by engraving a plate crossed over into the technique of this painting, where Picasso gave texture to the flesh of the figure with deep and deliberate troughs.

The three-dimensional depth of these lines is captured by high-resolution microscopy (fig.17) which reveals a deep trench, created with a rounded instrument while the paint was still soft and malleable.

The transformation from boy to girl

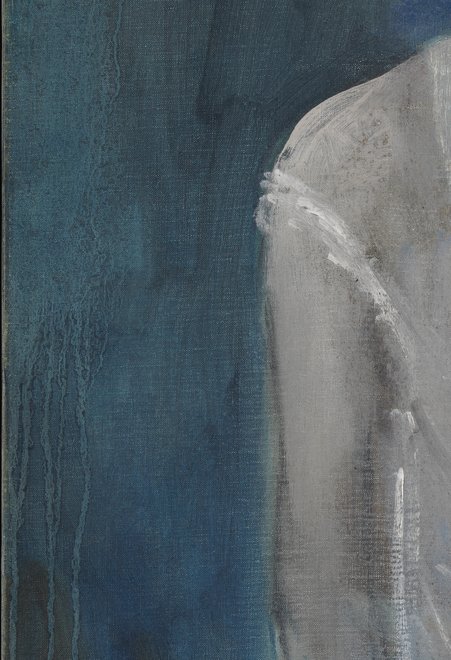

The transformation of the image from the young male saltimbanque to the fragile, beautiful portrait of a young woman was carried out with a series of minimal interventions. The boy was transformed partly with subtle changes to the contours of the head (fig.18a–b). His rounded head was covered with a feminine chignon, which has the effect of elongating the whole head. The hair shimmers with added strokes of pure blue, the dark brown and black hair brushed in thin lines rather than a solid block of colour, allowing the blue to dominate. The forehead is adorned with wisps of hair. A thick application of ultramarine blue beyond the profile has redefined the outline of the face and the back of the head and cut into the shoulder under the chin, lowering the proper left shoulder and creating a longer neck. The chin itself was changed from a sharp, pointed, downward-facing chin to a more rounded feminine shape with a deeper indentation beneath the lips. The proper left arm of the girl was scooped in below the shoulder, whereas the boy’s arm seemed to continue in a straight line. This allows for the girl’s breast to be in clear profile against the dark background.

Picasso squared off the nipple with a black outline around the brushy flesh paint, and the ultramarine backdrop was applied after that black line, overlying it in places (fig.19). The bright blue colour, against the complementary background of warm brown, makes the shape stand out from the background, accentuating the femininity of the figure.

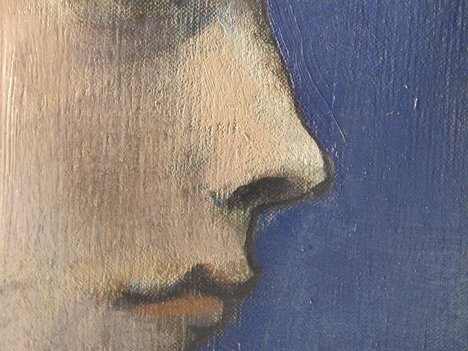

The thin boyish lips were altered and given definition, with a fuller bottom lip, this time coloured red, and a sharply curvilinear upper lip, achieved with the stroke of a black outline (fig.20). This curved upper lip seems to be a distinctive feature of Madeleine herself, as depicted in Head of a Woman in Profile (fig.16) and Friends (fig.3), even though in the latter image she is obscuring some of her lips with her hand. The sharp tip of the lip profile is also defined with the black outline. The paint layers beneath the lips are a complex system of scraped-back paint, revealing blue and grey beneath, and roughly textured flesh colour which appears to have been brushed down towards the lip while leaving a small area of the blue underpaint free to add depth to the shape of the lips. The lips then received a brushstroke of vermilion, an intensely red pigment, both on the bottom lip and above the black line in the upper lip. The black outline of the lips goes over this and was therefore added last. All the brushstrokes were applied fairly dry, and they lie on the surface of the canvas peaks, allowing all the underlying colours to make an optical contribution.

The female nose (fig.21) is sharper than the boy’s nose and the nostrils appear more prominent than those in the X-radiograph, the nose having an upward slant. The pointed tip is defined by the black outline and the blue of the ultramarine background seems to have been applied up to and in places following the black line, therefore afterwards. There is more space between Madeleine’s nose and upper lip and there is more of a right angle between the base of the nose and the straight profile above the upper lip, in comparison with the boy. There is a brushstroke of warmer flesh paint applied to the nose, which does not quite reach the outer edges.

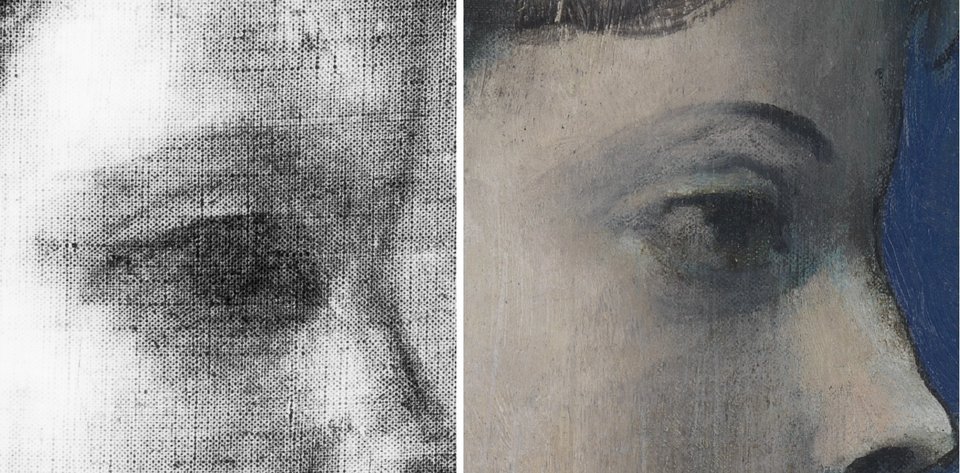

The ear in the X-radiograph (fig.22a) appears as more of a shadow, less defined than the girl’s ear (fig.22b). Picasso refined the outline with flesh paint, leaving dark blue underlayers to create the shadows. A brushstroke of transparent brown creates a hollow in the inner ear. The flesh paint above the ear was applied before the brown of the hair, which lies over the pink. The thick application of pink flesh paint in the upper section of the ear and the ear lobe appear in both the X-radiograph and the upper work, and Picasso added a shadow on top of the flesh paint beneath the lobe to sharpen the profile.

The wide, rounded eye of the boy (fig.23a) was shaped into a more hooded, feminine eye (fig.23b) with the addition of veils of flesh paint and dark shadows below and at the bridge of the nose. Picasso scraped through to a pale blue layer towards the nose and in the eyelid which gives it the more haunting look of someone with dark rings under the eyes. The upper eyelid (fig.24) reveals blue paint from an underlayer, vertical strokes of flesh paint scarcely concealing dark grey canvas peaks beneath, with a smoky grey blended brushstroke then adding depth to the fold of the eyelid. The black line of the eye is sharp and clearly defined, possibly added as the last stroke to create the final shape.

The torso (fig.25) has a complicated layer structure of dark underpaint, thick dry white impasto of the boy’s collar, thin veils of flesh colour and transparent blue over which Picasso laid in the chemise in thick, pure white impasted lines. The chemise is defined by a very few of these lines, while the complex underlayers were utilised to create shadows and depth to the shapes. The flesh colour was quite fluid and it defines the shoulder (fig.26) with loose brushstrokes. The white impasto of the straps picked up the wet flesh colour from rapidly applied strokes. The strong outlines of the torso lift the slender figure out of the background, but the lines themselves are subtly crafted. They are not pure black but are blended from grey to black to give the outlines a more three-dimensional appearance.

The line at the lower-right edge of the torso was blended from a dark grey to pure black (fig.27). This gives the line a soft, nuanced outer contour emerging from the background and a sharp black inner line defining the body. The thin layers of paint around the line are a complex mixture of the scraped-down layers of pink and brown, with grey/blue washes above.

The washy blue background seems to follow the final contours of the body to create a lively yet ethereal backdrop for the delicate figure (fig.28). Picasso brushed a mixture of Prussian blue and diluted black paint over the scraped, absorbent base, and while it was still wet he seems to have allowed either solvent or very diluted paint to drip down the surface of the painting, cutting through the dark upper layer to reveal the colours beneath. Fig.29 shows the exposed fibres of the scraped canvas peaks, glimpses of white ground, a pale blue paint layer and then dark blue in the valleys of the canvas texture, all contributing to the dark blue/black background. Much of the background includes Prussian blue, probably cerulean blue as well, and the actual range of pigments across the surface is limited to these two blues, two reds (vermilion and mars red), brown earth pigments and limited use of black. Other works from Picasso’s blue period have been found to include precisely the same range of colours.24

The ultraviolet (UV) image shows many different fluorescent materials in the painting, which in itself suggests that the painting does not have an overall varnish (fig.30). The runs in the background fluoresce in UV which can indicate an oil paint with added natural resin, or more likely here, thinned with oil of turpentine. The white has a slight greenish tinge, suggesting zinc white in the impasted lines which denote the chemise. The ultramarine blue used almost unmixed around the head is distinct from the Prussian blue of the background and was scarcely used elsewhere, which gives it a powerful presence that make the girl’s blue-toned flesh glimmer out from the blue-toned background.

It is also interesting to note that the signature (fig.31) was scraped back to reveal white canvas peaks, whereas the date was applied on top of the peaks and over a dried solvent run. This implies that the date was a later addition than the signature, which could account for the later inscription of ‘’05’ instead of the date Kahnweiler gave as 1904.

Conclusion

Girl in a Chemise is an immensely complex painting which evolved through several campaigns of painting by Picasso. The canvas was reused by the impecunious artist, who was starting out in Paris with very little to his name and who often re-used canvases during this period: the shadowy semi-circle in the right-hand side and the rounded figure hint at traces of another work altogether.25 Viewing the X-radiograph alongside Mother and Child, Acrobats (fig.6) suggests that Picasso was experimenting with a similar mother and child image in the Tate work, with the ghost of the mother figure remaining in the upper-left corner after scraping.

The first clearly recognisable painting on this canvas was a thin boy with elements of a Pierrot costume, maybe a study for a larger work or a finished work in its own right on the theme of saltimbanques which Picasso made his own. Picasso then changed his mind and with continued scraping and removing of upper layers transformed the young male figure into a delicate portrait of his mistress Madeleine. The subtle changes from boy to young woman were carried out with deft brushstrokes and a minimum of paint, the scraped-back paint layers remaining part of the shadows and yet contributing very significantly to the subtly shifting surface colours. Having outlined the head, neck and breast with black, he painted a bright ultramarine blue around the edges of the figure to make it stand out and sing against the vibrant background. The rest of the background was then enlivened with thinned, broad brushstrokes and cut through with runs of solvent which reveal the complex layer structure beneath. Despite the complete transformation from male to female, Picasso did not seem to consider it important to conceal completely the ruff of the young acrobat’s costume in her naked décolletage and even though the upper paint layers will have become more transparent with time, the ruff would likely always have been visible to some degree, in some lights, and from some angles of viewing.

The painting was not varnished by Picasso and remains unvarnished. Thus the subtle matte quality of the highly thinned paint can be appreciated and contrasted with the sparse impasted brushstrokes that define the chemise. The subtly shimmering colours of the background were achieved with oil-based paint, large quantities of a thinner such as oil of turpentine, and a mere handful of coloured pigments including only two or three blues, one red, browns, with white and black used sparingly, and with great technical control.

This painting is predominantly blue, but the warm pinkish brown undertones in the background and the touches of intense vermilion on her lips represent a change towards to a lighter and more colourful palette. The great saltimbanque paintings of Picasso’s rose period are perhaps heralded in this small work. Picasso was working in many different media at this stage of his career, experimenting with engraving, making small paintings in gouache to achieve a flatness in the vague backgrounds, from which his saltimbanque figures would emerge. It is interesting to note that several of the techniques and effects he achieved with these materials have re-emerged in this painting, re-enacted in oil paint.

Seen in the context of Picasso’s career this painting is considered one of his early works, but the technical accomplishment and the creativity of the artist are fully evident by this period. His limited palette was masterfully deployed, his very physical engagement with the painting process evident in the scraping and scoring of the paint, the juxtaposition of opaque matte colours and washes of transparent colour combining to produce this small but significant painting at a key transitional moment in his career.

- 1.See Marilyn McCully, Picasso: The Early Years 1892–1906, New Haven and London 1997, p.41.

- 2. Ibid.

- 3.Daniel H. Kahnweiler started handling Picasso’s artworks in 1908 and became Picasso’s dealer in 1912.

- 4.Daniel H. Kahnweiler, letter to Tate Gallery, 21 February 1953, Tate Public Records.

- 5.Daniel H. Kahnweiler, letter to Tate Gallery, 5 May 1954, Tate Public Records.

- 6.Pierre Daix, La Vie de peintre de Pablo Picasso, Paris 1977, p.61.

- 7.John Richardson, A Life of Picasso, vol.1, 1886–1906, London 1992, pp.295–307.

- 8.Ibid., p.304.

- 9.Ibid., pp.303–4.

- 10.Ibid., p.304.

- 11.Mother and Child 1904, black crayon on paper, 33.8 x 26.7 cm, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Bequest of Meta and Paul J. Sachs.

- 12.Richardson 1992, p.304.

- 13.See Woman with Helmet of Hair 1904, Art Institute of Chicago, http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/68414, accessed 15 November 2017. The model for this painting is possibly another model who sat for Picasso at this time, Antoinette Fornerod. With thanks to Marilyn McCully for pointing this out through personal communication with the authors, 15 August 2017.

- 14.See Elizabeth Cowling, Picasso: Style and Meaning, London 2002, p.119.

- 15.See Marilyn McCully, Picasso in Paris 1900–1907, London 2011, p.142.

- 16.This simple method of framing was known as a baguette and was used by Picasso.

- 17.Selvedge are the long edges of woven fabric, and smaller pieces of cloth would normally be measured and cut out around this naturally non-fraying border. If a canvas the full width of the fabric is being primed by the colourman, it is equally natural to attach it by the selvedges for priming, leaving two unprimed strips of selvedge.

- 18.Analysis carried out in-house at Tate included optical microscopy of cross-sections made c.2000–3 by Fotini Koussiaki, Royal College of Art doctoral candidate, which were re-examined and compared to a few new ones. It was impossible to justify new samples elsewhere than the edges which had been sampled previously. This enabled some pigment identification, backed up by scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis, portable X-ray-fluorescence (pXRF) and fibre-optic reflectance spectroscopy (FORS), the last two carried out by Dr John Delaney and Kate Dooley, with Julie Barten. The paint medium and some other constituents were investigated with Fourier transform infrared microscopy.

- 19.Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘Les Jeunes: Picasso, peintre’, La Plume, 15 May 1905, translated in A Picasso Anthology: Documents, Criticism, Reminiscences, ed. by Marilyn McCully, Arts Council of Great Britain, Musée Picasso, Paris, Hayward Gallery, London 1981. p.52.

- 20.McCully 2011, p.151.

- 21. Ibid.

- 22.Head of a Woman in Profile 1905 is probably one of the twelve proofs previous to the waxing of the plate.

- 23.Fernande Olivier quoted in McCully 2011, p.140. See also Fernande Olivier, Loving Picasso: The Private Journal of Fernande Olivier, trans. by Christine Baker and Michael Raeburn, New York 2001, p.139.

- 24.See Allison Langley, Kim Muir and Anikó Bezúr, ‘Looking Below the Surface of Picasso’s The Old Guitarist’, in Arie Wallert (ed.), Painting Techniques: History, Materials and Studio Practice, Amsterdam 2016, pp.258–63; and Catherine Defeyt, Philippe Walter, Hélène Rousselière, Peter Vandenabeele, Bart Vekemans, Louise Samain and David Strivay, ‘New Insights on Picasso’s Blue Period Painting La Famille Soler’, Studies in Conservation, forthcoming 2017.

- 25.Many examples of Picasso’s re-use of canvases and cut-down fragments of larger canvases from this period were presented at the symposium ‘Early Picasso: The Development of the Artist through his Palette’, held at the University of Barcelona and the Museu Picasso, Barcelona, on 27 February 2015. Not all the papers have been published at the time of writing, but one example is Langley, Muir and Bezúr 2016, pp.258–63.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to the Clothworkers’ Foundation who generously supported the two-year technical study of Picasso, Picabia and Ernst at Tate during 2014–16. The digital X-ray equipment was acquired by Tate during the project with the generous support of the R. and S. Cohen Foundation. Huge thanks go to Dr John Delaney and Dr Kate Dooley of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., for coming to London and bringing SWIR imaging, pXRF and FORS equipment in 2013, and applying these to Girl in a Chemise, and to Julie Barten of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, for her role in this study and for sharing research on Woman Ironing 1904. Thanks also to Ann Hoenigswald and Jennifer Hickey at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. for generously sharing their research on Lady with a Fan 1905 by Picasso. Many thanks to Reyes Jiménez-Garnica of the Museu Picasso, Barcelona, for generously sharing her research and her interpretation of the X-radiograph. Thanks to Tate Photography and in particular Marcella Leith, Mark Heathcote, Rod Tidnam, Joe Humphries, Jo Fernandes, Lucy Dawkins and Rose Hillson-Summers who have taken such beautiful and instructive images and X-radiographs, and processed the images. Thanks also to the art handling team and registrars at Tate for frequent art movements and continued access to the painting. Thanks to former Tate Conservation Science intern Nelly von Aderkas for her contribution to the analysis of this painting. The high-resolution micrographs were taken using a Hirox KH-8700 digital microscope, the purchase of which was supported in part by the Nanorestart research project funded by Horizon2020; others were taken by Emilien Leonhardt and Dr Jaap Boon in 2013 when they kindly brought a similar microscope to Tate for use on another artwork. Dr Marilyn McCully generously shared her knowledge of this painting, and commented on the text.

Annette King is a Paintings Conservator at Tate

Joyce H. Townsend is Senior Conservation Scientist at Tate

Bronwyn Ormbsy is Principal Conservation Scientist at Tate

Joyce H. Townsend is Senior Conservation Scientist at Tate

Bronwyn Ormbsy is Principal Conservation Scientist at Tate

Tate Papers, Autumn 2017 © Tate

How to cite

Annette King, Joyce H. Townsend and Bronwyn Ormsby, 'Girl in a Chemise c.1905 by Pablo Picasso', Tate Papers, no.28, Autumn 2017, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/28/picasso-girl-chemise, accessed 2 September 2018.

Tate Papers (ISSN 1753-9854) is a peer-reviewed research journal that publishes articles on British and modern international art, and on museum practice today.

Tate Papers (ISSN 1753-9854) is a peer-reviewed research journal that publishes articles on British and modern international art, and on museum practice today.

No comments:

Post a Comment