Pablo’s people: the truth about Picasso's portraits

The painting that greets you at the entrance to the National Portrait Gallery’s autumn show is Picasso’s famous Self-portrait with Palettefrom 1906. It’s pre-cubist but post-blue period, so the young man’s eyes, ears and nose are all pointing in the same direction and his hair isn’t marine-coloured, but a proper Iberian lacquer black. There’s a blank, mask-like quality to the face, yet Picasso is instantly recognisable in the broad fleshy nose and bull neck. At the same time the painting is a clear homage to an earlier self-portrait by Cezanne – there’s the same austerity, the same workmanlike setting – as well as exhibiting a cousinship with Picasso’s own triumphant image of Gertrude Stein, also from 1906 (that basilisk stare and sand-coloured skin). What’s more, by choosing to pose with the paraphernalia of his profession, Picasso puts himself in a tradition of classic portraiture that stretches back centuries to his beloved Goya and Velázquez.

The young Picasso began his career with the long apprenticeship in the human form that every art student, whether in London, Rome, Paris or indeed Barcelona, was obliged to undergo. First came the endless drawing of canonical antique sculpture, then graduation to the life class. Typical too was the insistence of Picasso’s art teacher father that his boy should master the knack of producing “likenesses”, briskly and to order. Portraiture was a steady, well‑paid gig (there were always people vain enough to want to see themselves in paint), and it got you an entrance into the best circles. At the very least, you’d always be able to pay the rent.

But these lapdog aspects of professional face-painting were anathema to Picasso. He never took on a commission and any notable people he painted during his long career – Stein, Stravinsky, Cocteau – were only there by chance, because they were friends or colleagues or had an interesting arrangement of flesh and bone that he itched to get down on paper. And rather than include a famous subject’s name in a painting’s title, Picasso often used the broadest descriptions, such as Woman Ironing or Cubist Head.

Not every sitter was thrilled by these erasures. Dora Maar, Picasso’s lover from the late 1930s, famously said of his pictures of her: “they’re all Picassos, not one is Dora Maar”. But the fact that she made the claim in the bitter years after their relationship ended is often overlooked, allowing the idea to flourish that Picasso was a monomaniac who absorbed other people’s faces into his greedy art with little care for what made them unique. The fact that he often dismissed his sitters after a few hours, preferring to work from their photographs instead, only added to this suspicion that he was not a portraitist but a Picasso-ist, intent on remaking the world, and everyone in it, in his own image.

This is unfair, says Elizabeth Cowling, the curator of Picasso Portraits. And to prove it she has grouped together three portraits of three different women painted within a few months of each other in 1938. In Woman With Joined Hands Picasso presents his longtime lover Marie-Thérèse Walter with soft, loving intimacy. Despite being rendered in graphic greys and blacks, Walter resembles nothing so much as a comfortably padded sofa, all folds and creases and cushiony cross-hatching. At the same time her body’s sinuous contours suggest a surging eroticism, one that speaks of pleasurable sexual familiarity rather than piercing desire.

Just a month later Picasso drew Nusch Éluard, the wife of his friend the surrealist poet Paul Éluard. Éluard, a professional acrobat with a light, pliable body, is conveyed in tight angles and wafer-thin planes, her wiry hair rendered in hard squiggles. There is none of the placid softness of Walter in evidence here, and Éluard’s outsized claw-hand is a pointed joke that acrobats, like cats, have nine lives.

Completing the trio of female portraits from 1938 is Dora Maar Seated. Here Picasso draws his lover, with whom he started a relationship while still with Walter, in a swirl of calligraphic doodles that double crazily back on themselves. This tortured frenzy matched what Picasso called Maar’s “Kafkaesque” personality. Beneath the hectic surface of ink and thinned-out gouache you can make out her tightly clamped-together legs (the couple rowed frequently) as well as references to her studied self-presentation as a Spanish señora straight out of Goya (she was actually French-Croatian). Despite what Maar liked to say, this could only be her.

Picasso’s insistence on matching his style to the idiosyncrasies of each sitter has its roots, suggests Cowling, in the artist’s lifelong practice of caricature. Starting as a schoolboy in the 1890s, he delighted in making swift, scabrous sketches of his friends on napkins, torn up bits of paper bag, in the margins of his textbooks. As an adolescent he drew doodles of his art school colleagues, and later it would be dealers, patrons, rivals and friends, whom he dashed down in a few bold strokes – here an elongated neck, there a ridiculous moustache or odd pair of glasses. These were in-jokes, a way of cementing bonds in a homosocial atmosphere that was also deeply competitive: so the artist Josep Rocarol i Faura is drawn, flushed and sloppy from too much absinthe, while the small and prudish Jaume Sabartés is shown leering at nubile pin-ups ripped from magazines. The poet Guillaume Apollinaire is made into a fat businessman (he was actually a bank clerk) with a pear-shaped head. Far from being insulted by his friend’s view of him, Apollinaire treasured Picasso’s scrawls as tokens of affectionate attention.

It has been customary to ignore this aspect of Picasso’s work, to classify his caricatures as byproducts – waste products, even – of the finer kind of art with which he was concerned over six decades. But, suggests the exhibition, it was in these quick-fire sketches that he honed the ability to edit, distil and exaggerate details that allowed him to produce portraits that went far beyond mere surface likeness, and penetrated instead to the essence of each sitter. “There are so many realities that in trying to encompass them all one ends in darkness,” Picasso once explained. “That is why, when one paints a portrait, one must stop somewhere, in a sort of caricature.” Later, this too became pithily contracted to “all portraiture is caricature”.

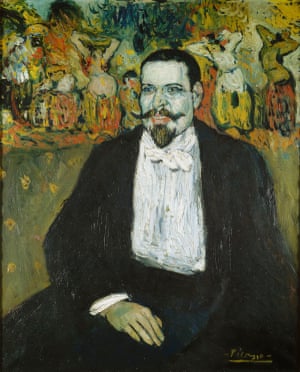

You can see this principle at work in an early portrait of Gustave Coquiot, a louche Parisian critic about town. The portrait is a thank you present for a nice review that Coquiot had recently written of the young man’s work, yet there is nothing remotely ingratiating about it. Coquiot is shown with a wet lascivious grin sheltering under a ludicrously twisty moustache while near-naked showgirls bump and grind in the background. Coquiot’s hand, resting on his lap, looks as though it is positioned to conceal an incipient erection. But if this is smut, it is smut with a point to it: in setting and style Picasso knowingly channels Toulouse-Lautrec, the pre-eminent genre painter of Parisian flânerie, an art historical reference he knew would tickle Coquiot’s vanity.

Even when Picasso moved decisively away from descriptive naturalism, there is never any sense that he is slighting his human subjects. Instead, he sought always to find the details that made individuals instantly recognisable to themselves and to others. One of the jewels in the NPG exhibition is Picasso’s 1910 portrait of art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, a cubist masterpiece that rarely leaves the Art Institute of Chicago. At first glance the picture seems to be merely a metre-high arrangement of grey and sludge-coloured squares. Gradually, though, the eye settles and the pattern resolves so that beneath the facets you begin to see the soft but certain form of a bourgeois man. There is his beaky nose, his wings of oiled wavy hair, his neatly folded hands, his watch chain.

Far from being random, each of these details is part of a caricatural shorthand. Kahnweiler was famously punctual, which explains the watch chain. He was notoriously abstemious, hence the way that the wine glasses that so often figure in cubist paintings have been replaced on this occasion by medicine bottles. These in-jokes add up to an image that is designed to be instantly readable to those who knew Kahnweiler well, yet still speak to those who have never set eyes on the subject of Picasso’s portrait.

Nor did Picasso paint his people in an eternal present. He used his repertoire of gestures honed from years of doing caricatures not to generalise about a face, to fix it for all time, but to capture its quiddity. Some of the most expressive pieces in the exhibition are those of his many lovers during the dying days of their relationships. Woman in a Hat (Olga) (1935) shows his first wife’s face segmented between sickly chalk white and venomous green. Her eyes are deep black holes, staring with fatigue and disappointment, while her mouth is a downward slit. The stiffly lacquered hair and purple hat, meanwhile, speak of a desperate need to put a good face on things going very wrong indeed. Its fractured desperation stands in extraordinary contrast to the luminous neoclassical portrait Picasso had completed of Olga 12 years earlier in which she is portrayed as entirely in charge of herself, as serene as a Roman matron.

And then there is another woman in another hat, this time from 1941. It is Dora Maar, painted at the moment when she and Picasso returned to Nazi-occupied Paris to discover horrors that they could not quite believe. Like Olga, Dora is trying to hold herself together, smart in a business-like suit. Her jaunty hat, however, is woefully small for a giant head that looks anxiously in two directions at once, alert to the sound of tramping boots or a knock on the door. Her body, rigid with fear, seems to have become fused to the chair on which she perches (even Picasso’s most non-naturalistic portraits used the standard seated pose from classical tradition). And then there are the hands, clawed with tension, the nails painted a ripe red, suggesting that a fight to the death may already be going on in the streets below. Here, surely, is Picasso’s definitive riposte to anyone who maintained, still maintains in fact, that his portraiture was indifferent to its subjects and careless about their circumstances. What he had actually done was take a moribund tradition, concerned with commemoration of the blandest kind, and wrench it back to thrilling life.

No comments:

Post a Comment