A meticulous study of Anna Whistler, by Daniel E Sutherland and Georgia Toutziari, is a treasure trove of odd information

Kathryn Hughes

Saturday 12 May 2018

Saturday 12 May 2018

Over the last century and a half Whistler’s mother has been having a high old time. Perhaps 1934 was the giddiest year: Cole Porter name-checked her in “You’re the Top” while the US government put her on a postage stamp to celebrate Mother’s Day.

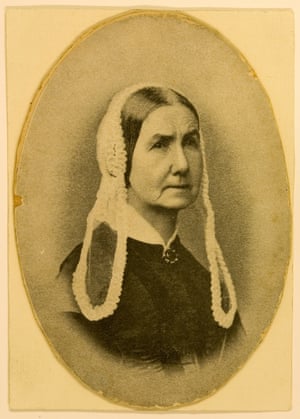

More recently the playwright Edward Bond turned her into the devil in a wheelchair in Grandma Faust, while in 1997 Rowan Atkinson gurned in front of her as Mr Bean. Whenever Whistler’s Mother (its official title isArrangement in Grey and Black No 1) tours the world, gallery crowds flock to stare at the elderly, seated figure staring enigmatically into the middle distance.Along with the Mona Lisa and Girl With a Pearl Earring, she has become an instantly quotable pin-up of popular art. Which is odd because “Whistler’s mother” doesn’t exist, not really. The fact that the woman in the picture was indeed the artist’s mother was not, at least for James McNeill Whistler, the point at all. The London-based American painter had no interest in doing family portraits – Anna Whistler was a stand-in for someone who hadn’t turned up – nor was he concerned with conjuring up “wisdom”, “age” or even “mothers” in general. As the picture’s real title suggests, what actually drove him was the technical challenge of modulating tones of black and grey in a way that made them legible in half-light.

More recently the playwright Edward Bond turned her into the devil in a wheelchair in Grandma Faust, while in 1997 Rowan Atkinson gurned in front of her as Mr Bean. Whenever Whistler’s Mother (its official title isArrangement in Grey and Black No 1) tours the world, gallery crowds flock to stare at the elderly, seated figure staring enigmatically into the middle distance.Along with the Mona Lisa and Girl With a Pearl Earring, she has become an instantly quotable pin-up of popular art. Which is odd because “Whistler’s mother” doesn’t exist, not really. The fact that the woman in the picture was indeed the artist’s mother was not, at least for James McNeill Whistler, the point at all. The London-based American painter had no interest in doing family portraits – Anna Whistler was a stand-in for someone who hadn’t turned up – nor was he concerned with conjuring up “wisdom”, “age” or even “mothers” in general. As the picture’s real title suggests, what actually drove him was the technical challenge of modulating tones of black and grey in a way that made them legible in half-light.

He had done something similar nearly 10 years earlier in The White Girl when he’d painted his mistress Jo Hiffernan in a froth of white on more white. Now here was another aesthetic experiment, this time at the opposite end of the colour spectrum.

For a painter who said he wasn’t interested in mimetic portraiture, illustrative anecdote or symbolic signalling, it’s ironic that Whistler is now best remembered for a painting that appears to do all three. There’s something telling, too, in the fact that Anna Whistler herself never seemed to grasp that she was only there as a useful arrangement of shape and volume rather than as a subject who actually mattered.

When Whistler finished the picture and murmured “Oh Mother … it is beautiful,” it was his handiwork he was admiring, not her bone structure. And there’s no getting away from the odd fact that, while everyone agreed that the picture was the very spit of Anna, they quickly spotted one deliberate distortion. Instead of an accurate rendering of her neat little patrician slippers, Whistler had given his mother “sprawling, flat peasant feet”.

Daniel E Sutherland and Georgia Toutziari are adamant that we shouldn’t try to read anything into this. Yet they proceed to offer such a treasure trove of odd information about Whistler mère et fils that it seems a dereliction of curiosity, duty even, not to probe further.

You can’t help noticing, for instance, how strangely the flesh-and-blood Anna was positioned in her adult son’s life, managing to be simultaneously at its centre and entirely to one side. Living around the corner from his studio in Chelsea, the American-born widow acted as “Jemie’s” amanuensis, agent, cheerleader and chief scold. She prepared lunch for visitors at his studio, nagged him to number his engravings in order to boost their market value, and told him to make friends with important people who might buy his work. She remained hugely proud of what she called “my painting”, claiming it not just as a portrait but as an emblem of the contribution she had made to her darling son’s career.

“He always confides in his mother,” Anna approvingly told her friends which, unsurprisingly, turns out to be the opposite of true. Whistler was instead careful to present his mother with a tightly edited version of his extremely rackety life. Whenever she met his disreputable male friends, they were instructed to be on their best behaviour. How else can one explain the fact that this deeply religious woman believed the boisterously drunk and gay Algernon Swinburne to be a delightful young man fit to be her honorary son?

And as for Hiffernan, Jemie’s Irish mistress, Anna seems to have thought that she was nothing more than his favourite model. When in 1870 the girl-mad Whistler had an illegitimate son by a local chambermaid, the news was kept from Anna, who sailed on oblivious, offering prayers and tracts to anyone she thought looked spiritually peaky.

While Sutherland and Toutziari are meticulous in rendering the busy life of Anna Whistler – she crossed the Atlantic 11 times as she followed her peripatetic husband and sons around the world – they remain uninterested in teasing out the emotional resonances of these constant dislocations. What we get instead is a respectful portrait of a woman who prided herself on her moral restraint and good breeding, yet whom, for some unaccountable reason, her son decided to paint with cumbersome feet that appear poised to step on other people’s toes.

• Whistler’s Mother: Portrait of an Extraordinary Life is published by Yale.

No comments:

Post a Comment