Interview

Peter Lindbergh: ‘I don’t retouch anything’

The photographer who created the supermodels talks to Tamsin Blanchard on the eve of his exhibition

F

lying into Rotterdam as the early mist hangs over the seemingly endless docks, it strikes me that this is an appropriate location in which to meet the photographer Peter Lindbergh. This is the man who has made raw images his signature – whether a stark electricity pylon shot in the industrial city of Duisburg, Germany, where Lindbergh grew up, or the untouched portrait of a model’s face, apparently devoid of make-up or any other such artifice.

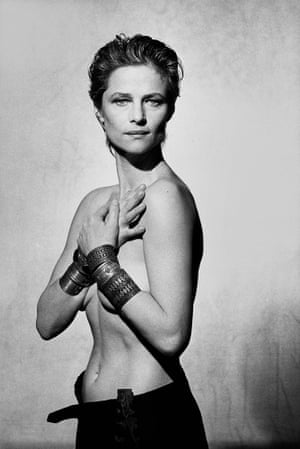

In fact, if I had arrived the previous day, I might have seen Lindbergh in action in one of the semi-derelict warehouses where he was photographing the 32-year-old model Lara Stone. The shoot is a commission by Dutch Vogue to coincide with “A Different Vision on Fashion Photography”, an exhibition of Lindbergh’s work which opens this September in Rotterdam.

I met Lindbergh at Rem Koolhaas’s Kunsthal, where he was editing the Lara Stone images with the show’s curator, Thierry-Maxime Loriot. “I see him more as an artist,” Loriot told me. “He has such strong themes. You can immediately say, ‘That’s a Lindbergh image’ because of the timelessness of the portraits, without make-up, without hair. They never date.”

Lindbergh does what he does. And as long as you don’t try to retouch what he does, he is happy. A warm, round bear of a man, his glasses perched on the end of his nose, he shows me some of the images of Stone. Someone had suggested that her nose was a little red. Unlike much of his work, the picture is in colour. Lara, her hair rough and messy, stares back at me looking powerful, womanly, slightly lined, and yes, a little pink around the nose. “She looks absolutely fantastic… raw, the same power as Kate [Moss],” he says. He shakes his head. “But who cares if her nose is red? You don’t see the power and the poetry of not being perfect?”

Magazines have to sign a contract agreeing not to do any retouching, otherwise, he says, it happens. “The cosmetic companies have everyone brainwashed. I don’t retouch anything. ‘Oh, but she looks tired!’ they say. So what if she looks tired? Tired and beautiful.”

Of course it helps if the subject is extraordinarily beautiful to start with. And Lindbergh is the man credited with discovering the supermodels, after all. He describes the iconic 1990 cover he shot for British Vogue – of Linda, Christy, Tatjana, Naomi and Cindy – as “the birth certificate of the supermodels”.

“I never had the idea that this was history,” he says. “Never for one second… I didn’t do anything, a bit of light. It came together very naturally, effortless; you never felt you were changing the world. It was all intuition.”

Two years before, Lindbergh had photographed a group of new faces including Linda, Christy and Tatjana for a story for American Vogue. The shots of the girls, windswept on the beach wearing nothing but plain white shirts, were totally out of kilter with the bold, glitzy, big-haired fashion then filling the pages of the magazine, and the editor at the time, Grace Mirabella, was not impressed. “She threw the pictures in the waste basket,” says Lindbergh.

Happily for him, Mirabella was fired not long after, and in August 1988 Anna Wintour took over and promptly hired Lindbergh to shoot her first cover. It signalled a complete change for the magazine – and for the mood of fashion in general. Wintour chose Lindbergh’s shot of the Israeli model Michaela Bercu. Her long, wavy hair is blowing in the wind. She is laughing, her eyes squinting in the sun. If she is wearing make-up, it is minimal. Her midriff, below a bejewelled Christian Lacroix top, is bare, and she is wearing jeans.

“I couldn’t stand the kind of woman who was featured in the magazine, supported by the rich husband,” he says, with a shudder, describing the pre-Wintour years. “I’ve never been impressed by somebody who came in with a crocodile bag, you know?”

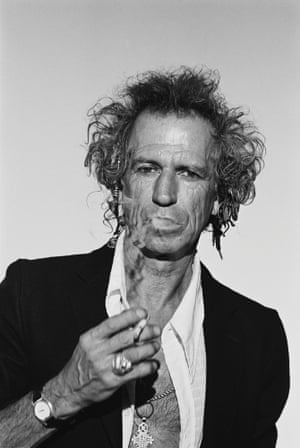

Of the many film stars and celebrities he has photographed, from Charlotte Rampling to Keith Richards, I wonder how he manages to circumvent the publicists’ ever-increasing demands for picture approval and retouching, or the agents who say he can only have half an hour with the talent. “I say: ‘Why don’t you fuck yourself and get out of here?’ – and I say it in a way they even say thank you.” He laughs, and I believe him.

That is part of his charm and part of how you get to be Peter Lindbergh. You have a vision. You don’t compromise on it for one minute, and you get your way – but always with a smile.

Lindbergh, 71, has been the subject of many exhibitions, and this one promises to speak to a new generation, not least because of the gallery dedicated to the “supermodels”. “I usually kick the supermodels out of exhibitions because it’s too commercial, but there is so much history – it’s forced me to look at them again.”

Although his photography is largely commissioned by and produced for fashion magazines, he uses clothes as props rather than the central element for the shoot. “I don’t even ask what outfit I’m shooting,” he says. But it is the advertisers who pay for the paper that the fashion stories are printed on (and when Lindbergh shoots for Italian Vogue, his stories will span at least 20 pages), so how does he feel about his photography being used as a vehicle to give clothing credits to those advertisers? “I don’t care what they slip in as long is it can integrate with the picture I want to do,” he shrugs. “But if it doesn’t fit, then I don’t care for the credits, I have to say.”

Lindbergh was born in 1944 in Lissa, in western Poland. When he was just two months old the family were forced by the Russians to flee. “What I know is my mum, my grandmother and my sister and my brother and I got on a little platform with two wheels and a horse, left there and ended up travelling 2,500km. Isn’t that incredible? In the war! We travelled through Berlin all the way down to south Germany, in the Alps.”

Lindbergh was the youngest of three children. His father was shot early in the war. “A sniper shot him, ripped off his fingers.” It probably saved his life as he worked in the barracks for the rest of the war. When he returned home, he became a salesman for a sweet company.

The family ended up in Duisburg, the centre of Germany’s steel industry. “We had no money. We had three small floors, for five people. Today when I go into my apartment I have a huge hall and big rooms with high ceilings!” His parents lived in the family home all their lives. “Duisburg was the worst industrial, depressive part of Germany. But it was great. We had nothing, but I didn’t miss nothing so that was fine.”

At 14 he left school to start work as a window dresser in a local branch of the Karstadt department store. He moved to Switzerland at 18 to avoid military service in Germany and then to Berlin, where he got a job at Karstadt again. But it wasn’t long before he started to see other possibilities.

“It was really exciting,” he recalls. “I had never seen an exhibition, an art book, I’d never listened to music, nothing. I’d never been in a museum before! I was like a dry towel – I sucked up everything.”

He enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts but soon decided to follow in the footsteps of Van Gogh and go to Arles to discover himself. He worked on a farm in the mornings and painted in the afternoons, selling his work in the markets to make some money. After eight months, like a proper beatnik, he set off hitchhiking around Europe and North Africa. Finally he returned to Germany. “I was about 20. I was lost to society: smoking pot, sleeping outside. Two years on the road is long. That is a lot of time to think. It made me a different man.”

Lindbergh discovered photography quite by accident. “My brother had fabulous children before I had children and for some reason I wanted to photograph them, and that was when I got my first camera. Children have something totally unconscious about them. That’s how I learned.”

Having established himself in Germany – he opened his own studio in Düsseldorf in 1973, shot the first ad campaign for VW Golf and his first fashion shoot for the prestigious Stern magazine in 1978 – he moved to Paris, where he has lived ever since. He has four children – all boys – and is married to Petra Sedlaczek, who is also a photographer (she started out assisting Lindbergh).

Like those of Steven Meisel, Bruce Weber and David Sims, his images continue to be relevant – rarely a Vogue Italia goes by without one of his stories. And while Lindbergh says the era of the supermodels is over, he tends to work with the same models over and over again – Lara Stone is a current favourite, as are Mariacarla Boscono, Kate Moss and Kristen McMenamy. Like a choreographer, these are his dancers and it’s not about finding the new all the time, but building a relationship and creating a style that is beyond fashion.

He draws my attention to his image used for last year’s ad for the Calvin Klein fragrance Eternity. “It was Mark Vanderloo and Christy Turlington, very simple, just the two of them, looking at the camera. And it was done 25 years ago and they just used the same image again and nobody figured it out. It looked just like from yesterday, which was really nice. If you don’t do anything, what could age in that picture?” he asks. He sits back in his chair, and smiles. “Nothing!” And that’s the truth.

No comments:

Post a Comment