Emmanuel Carrère: the most important French writer you've never heard of

As his latest 'non-fiction novel', Limonov, comes out in English, the acclaimed and bestselling author discusses his extreme personal candour and why he likes to court danger

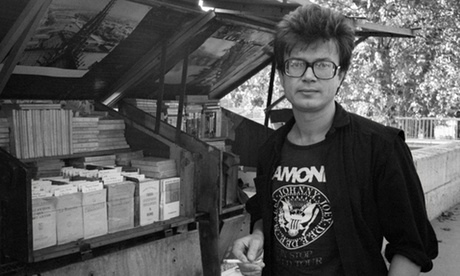

Emmanuel Carrere: ‘Yes, maybe I’m more explicit than some.’ Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP

Relaxing cross-legged in his Paris apartment, with his crew cut, bare feet, and black fatigues, sun-tanned Emmanuel Carrère could be a guerrilla commander at a ceasefire, or a colonel in the French Foreign Legion enjoying some metropolitan R&R. In fact, he's the best kind of writer, not just a bestseller but a man who is not afraid to leave the comfort zone of his desk, go out into the world, take risks, and get his shoes dirty. According to the Paris Review, "There are few great writers in France today, and Emmanuel Carrère is one of them."

And yet, perhaps because he conducts himself less like a grand homme de lettres, and more like a journalist and film-maker, with discretion, modesty and good humour, Carrère's reputation has never progressed very far in the Anglo-Saxon world. Today, he is probably the most important French writer you've never heard of.

In part, this is to do with the range of his curiosity, his penchant for exploring many different genres, and the sheer variety of his life so far. He was born in 1957. After military service in Indonesia, he became a film critic for Télérama. While also writing screenplays for cinema and television, he has written several volumes of highly admired avant-garde fiction.

Carrère's breakthrough occurred in 1986 with The Moustache, a bestselling novella hailed by John Updike in the New Yorker as "stunning". Thereafter, he wrote a novel about a compulsive gambler (Hors d'atteinte?) and then a paedophile murder (Class Trip).

In 1993 he published I Am Alive and You Are Dead, a strange and obsessive inquiry into the life of Philip K Dick, the cult sci-fi writer whose work inspired movies including Blade Runner and Total Recall. Dick devoted his life to the unanswerable question, "What is real?". Similarly, Carrère seems happiest to work at what Graham Greene called "the dangerous edge of things."

The gap between the banality of everyday life and the wild wastes of his imagination is what fascinates Carrère. In his most recent book, Limonov, he writes: "I live in a calm country on the decline. Born into a bourgeois family in Paris's Sixteenth Arrondissement, I became a bourgeois bohemian in the Tenth. The son of a senior executive and an eminent historian, I write books and screenplays and my wife is a journalist. My parents have a holiday house on the île de Ré – more or less the French equivalent of Martha's Vineyard." Despite, or possibly because of, this inheritance, Carrère's imagination is anything but tranquil, or bourgeois.

First of all, he writes as if his parents are dead. In A Russian Novel, he portrayed his White Russian grandfather's wartime service in the Wehrmacht, for which he was executed as a collaborator, in stark defiance of his mother, the formidable Hélène Carrère d'Encausse, secretary-general of the Académie française. Her son, although awed by her achievements and celebrity, seems to relish the creative challenge presented by her example. "When I began to write," he says, "it was not so easy for me."

Elsewhere, he spares none of his family circle in print, including himself. Throughout his work, Carrère has pushed personal candour to the limit, exposing his worst self to public scrutiny. In the same novel, excruciatingly, he repeats the true story of the pornographic letter to his girlfriend he published in Le Monde.

It's no exaggeration to say that Carrère's life seems to be conducted, by accident or design, in extremis. For example, in 2004, he and his girlfriend took a Christmas holiday in Sri Lanka and were caught up in the tsunami.Other Lives But Mine, another bestseller, not only described their harrowing escape, but also grimly anatomised the death from cancer of his girlfriend's sister.

As if to elucidate his addiction to displays of the tormented self, he says: "I have had psychoanalysis for about 12 years in three different stages, with three different analysts. In France, there is a tendency to say that psychoanalysis does not work and that it is… " he searches for the word in a rare betrayal of his otherwise excellent English "fakery… quackery… crooked. But I feel grateful. Psychoanalysis has helped me as a man and as a writer."

Psychotherapy, he says, has contributed to his career as a novelist working at the dangerous edge. "For 15 years, I was a fiction writer. Then there was a moment when I wrote The Adversary [the true story of a serial killer] and I stopped writing fiction and began to write 'non-fiction novels'. I tried to write about the world and about myself, describing reality through my own experience. Yes, maybe I'm more explicit than some."

The writers Carrère admires are those like Montaigne, famous for declaring "I am myself the matter of my book", and Laurence Sterne, author of Tristram Shandy, who mash up art and reality and break literary conventions. "I like very much that kind of writer," he says. "A man whose mind is liberated and not caged in a genre, free from censorship."

In the manner of Truman Capote, whose quest for an ordinary mid-western murder story eventually became the classic "non -fiction novel" In Cold Blood, Carrère has waited, with the patience of a deer hunter, for the true story that would not only illuminate aspects of his own life, but also exemplify the puzzle of the post-cold war west.

In 2006, investigating the dark side of Putin's Russia, in the aftermath of journalist Anna Politkovskaya's killing, he found it in Moscow in the wrecked, transgressive figure of Eduard Limonov, the dissident nazbol, as Russians call members of the far-right National Bolshevik Party.

Eduard Limonov as a young punk rebel, 1980. Photograph: Sophie Bassouls/Sygma/Corbis

Eduard Limonov as a young punk rebel, 1980. Photograph: Sophie Bassouls/Sygma/Corbis

Limonov was tailor-made for Carrère's imaginative gifts. Born in second world war Ukraine, this dangerous, romantic rebel, "a cross between a sailor on leave and a rock star", had been a young punk in his native Kharkov, an avant-garde poet and idol of the Soviet underground in the Brezhnev era, and then an alcoholic down-and-out, before heading to America in the spring of 1974, coincidentally at the same moment as Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

As a refugee in 70s Manhattan, contemporary with the poet Joseph Brodsky, Limonov took a cheap room in the squalid Winslow hotel, living on cabbage soup, and writing about his life with the simple, raw energy of a Russian Jack London. While Limonov was making a minor literary name for himself, he also became a multi-millionaire's valet and published a sensational fictionalised memoir, His Butler's Story, with the Grove Press. About this chapter in an extraordinary career, Carrère says: "What interests Limonov is to be famous. The dream he has of himself is as the hero of a novel. He is not so proud of being a writer. He just wants to be a hero."

Has Limonov read Limonov, Carrère's account of his life? "Publicly, he says not," replies the writer. "Privately he says he disagrees with my version. But the book has had a great success, so Limonov does not mind."

After the American interlude, in another metamorphosis, Limonov moved back to Europe and became a louche, fashionable writer in 80s Paris, a city susceptible to the dangerous charm of the Russian émigré. Another scandalous novel, It's Me, Eddie, enjoyed a succès fou. "I knew him then," says Carrère, "but we were not friends."

Once again, Limonov's world fell to pieces. In 1989, the Soviet Union disintegrated in mayhem, euphoria and recriminations. As communism collapsed, Limonov disappeared into the Balkans. Here, to the horror of Carrère and his bien pensant circle, he ended up among the Serbs. "In our eyes," says Carrère, this was like "siding with the Nazis". A BBC documentary from this time shows Limonov bombarding the besieged city of Sarajevo under the benevolent eye of Radovan Karadzic. An important strand of Limonov is Carrère's anguished grappling with the demons of fascism from Nietzsche to Milosevic. "Limonov," observes Carrère, indulgently, "is the good incarnation of a fascist. Do not, as Pasolini says, underestimate the charm of fascism. To do that is not to understand a thing about Russia."

Still in search of existential and political coherence to his life as a post-Soviet citizen, Limonov returned to his homeland in 1994, coincidentally the same year as Solzhenitsyn. Mikhail Gorbachev had just been deposed by Boris Yeltsin. Limonov's response to the chaos in Russia was to found the National Bolshevik party, an aggressive neo-fascist movement appealing to disaffected, post-Soviet youth. Limonov's supporters occasionally popped up in news clips from the time: shaved heads, dressed in black, marching down Moscow's streets giving a half Nazi (raised arm), half Communist (balled fist) salute, and chanting "Stalin! Beria! Gulag!" The clear implication: Bring back the USSR. These, says Carrère, were Russia's "rock'n'roll years. Moscow was the centre of the world. Nowhere else are the nights so crazy, the girls so beautiful, the cheques so exorbitant." But then, out of this wild revel, like a wolf from the forest, came the cold, sinister figure of Vladimir Putin.

In 2001, Limonov was arrested, tried and imprisoned for obscure political reasons, apparently connected to arms trafficking and an attempted coup in Kazakhstan. When Carrère, who had known Limonov during his Paris heyday, encountered him again in 2006, he appeared, he says, "a little like an aged d'Artagnan", a telling clue to the direction of Carrère's interest in an extraordinary life story.

However, despite his novelist's attraction to Limonov's peculiarly Russian tale, Carrère could not reconcile the many characters locked inside the persona of Eduard Limonov (writer-hoodlum, hunted guerrilla, or post-Soviet politician). Perhaps telling his story would make sense of history? "I thought to myself," he writes, "[Limonov's] romantic, dangerous life says something. Not just about Russia, but about everything that's happened since the end of the second world war."

National-Bolshevik Party leader Eduard Limonov, arrested at an anti-Kremlin protest in Moscow, 2010. Photograph: Sergey Ponomarev/AP

National-Bolshevik Party leader Eduard Limonov, arrested at an anti-Kremlin protest in Moscow, 2010. Photograph: Sergey Ponomarev/AP

More than that, this bizarre life is a vivid mirror to Carrère's own complex personality, and his hidden drives. As a writer who relishes risk, he is fascinated by a life so connected to current events. His "non-fiction novel",Limonov, has two explicit modes – part adventure story, part cultural-historical analysis. It is, he insists, "not a biography. I never tried to do what a real biographer would do. I did not check facts, or check out what he actually said".

So, finally, and most covertly, it is about Carrère's exploration of himself, his Russian heritage, and what it means to be a European after the second world war, especially since the end of the cold war. He cheerfully admits to a sense of confusion. "I spent two weeks with Limonov," remembers Carrère "and after two weeks, I did not know what to think. Could this be a long article, or a book ? Not to know what you think is quite a challenge. It could be a biography, an adventure story, a roman picaresque, after Dumas, and also a book of history, with all the tension of a novel."

Life, however, rarely comes up with neat or satisfying narratives. Limonov still opposes Putin, with great courage, and is regularly thrown in prison for his pains. "The problem," says Carrère, "is that, basically, he supports Putin. He just thinks Putin is not hard enough. Limonov still dreams of a great Russia. But honestly," he concedes, "his career is over."

In Limonov, as a writer in search of a narrative line, Carrère struggles with this diminuendo. There's a moment in 2009, in one of his conversations with the ageing rebel, when he praises his "fascinating life – a life that dared to engage with history". Limonov's bitter response cuts the writer to the quick. "A shitty life, yes." Russian history is too merciless often to make ordinary life heroic and Carrère admits: "I don't like this ending."

This seems like a good moment to ask Carrère about his own French literary career. "I live a protected life," he says. "I have a nice apartment. My kids go to good schools." A shrug. "It's OK." That, apparently is Limonov's reproach to his biographer. "He says to me, 'We are not on the same side of the barricades. You are a bourgeois. I am a revolutionary. You are the kind of guy I would like to send to the gulag.'"

So where does Carrère put himself in the pantheon of contemporary French writing ? "Honestly?" he pauses. "I am quite well known. I am next to Michel Houellebecq. I am happy to hear that Julian Barnes is a fan. It sounds immodest to say this, but for the last 10 years I have been quite successful."

In Limonov, he writes of his younger self that "My ideal was to become a great writer." Was this at all an ironic self-description ? "Oh no." Carrère becomes quite serious. "That was always my dream. And…" He drops his voice almost to a whisper. "It still is." Then he rallies himself. "You should not confess that kind of thing. But really, it's not possible to write books if you don't have that dream."

Limonov: A Novel is published by Allen Lane on 21 October.

THE GUARDIAN

DE OTROS MUNDOS

DRAGON

No comments:

Post a Comment