1. Ill Seen, Ill Said by Samuel Beckett (1981). In terse, haunting prose, Beckett’s novella meditates on the absurdities of life and death, our grim longing for happiness, and “that old tandem” of reality and its unnamable “contrary.” The narrative itself, boiled down to poetic reflections, focuses on an old woman enduring her last days in a remote cabin. In the end, though all is blackness and void, Beckett wishes on us “grace to breathe that void,” even momentarily.

2. Notes from Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1864). Aloof, unhappy, and tortured by his own “hyperconsciousness,” Dostoevsky’s narrator prefers to remain underground, away from normal life, because at least there he can be free. When he forces himself to dine with three schoolfellows, their carefree laughter and drinking sends him “into a fury.” Afterward, he is seemingly moved by the plight of a young prostitute. But neither pity nor love is re deeming in this story whose narrator asks: “Which is better —cheap happiness or exalted suffering?” Dostoevsky’s preference is clear.

3. Ulysses by James Joyce (1922). Filled with convoluted plotting, scrambled syntax, puns, neologisms, and arcane mythological allusions, Ulysses recounts the misadventures of schlubby Dublin advertising salesman Leopold Bloom on a single day, June 16, 1904. As Everyman Bloom and a host of other characters act out, on a banal and quotidian scale, the major episodes of Homer’s Odyssey —including encounters with modern-day sirens and a Cyclops —Joyce’s bawdy mock-epic suggests the improbability, perhaps even the pointlessness, of heroism in the modern age.

4. Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann (1947). Mann retells the Faust legend as the story of wunderkind composer Adrian Leverkühn, who trades his human feeling for a brilliant career and demonic inspiration. Leverkühn’s biography, narrated by a faithful childhood friend from the vantage point of 1943 Germany, serves as a symbolic commentary on a nation’s cultural hubris and downfall. Mann probes the complex tensions between aesthetics and morality, culture and politics, in his trademark dense, precise, endlessly qualified prose. Given his theme —the culpability of genius in the sins of his society —the narrator’s almost infuriatingly overscrupulous command of language assumes a redemptive gravitas.

5. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

6. Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov (1955). “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul.” So begins the Russian master’s infamous novel about Humbert Humbert, a middle-aged man who falls madly, obsessively in love with a twelve-year-old “nymphet,” Dolores Haze. So he marries the girl’s mother. When she dies he becomes Lolita’s father. As Humbert describes their car trip —a twisted mockery of the American road novel —Nabokov depicts love, power, and obsession in audacious, shockingly funny language.

7. Austerlitz by W. G. Sebald (2001). During decades of travels through Europe, a nameless architectural historian accidentally keeps meeting Austerlitz, a neurasthenic architect who is incrementally confronting his buried connection to the Holocaust. Incantatory and almost vertiginous in its repetitiveness, this one-paragraph novel depicts the struggle of a personal narrative to melt the frozen memory of collective trauma.

8. Dirty Snow by Georges Simenon (1950). As this darkest of noirs opens, nineteen-year-old Frank Friedmaier, already a pimp, thug, and petty thief, has just become a murderer. What follows are searing portraits of the cruel and alienated young man who sees violence as a form of self-definition and the corrupt grim world that made him.

9. Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726, 1735). Lemuel Gulliver, a ship’s doctor, embarks on four wondrous voyages from England to remote nations. Gulliver towers over six-inch Lilliputians and cowers under the giants in Brobdingnag. He witnesses a flying island and a country where horses are civilized and people are brutes. Fanciful and humorous, Swift’s fictional travelogue is a colorfully veiled but bitter indictment of eighteenth-century politics and culture.

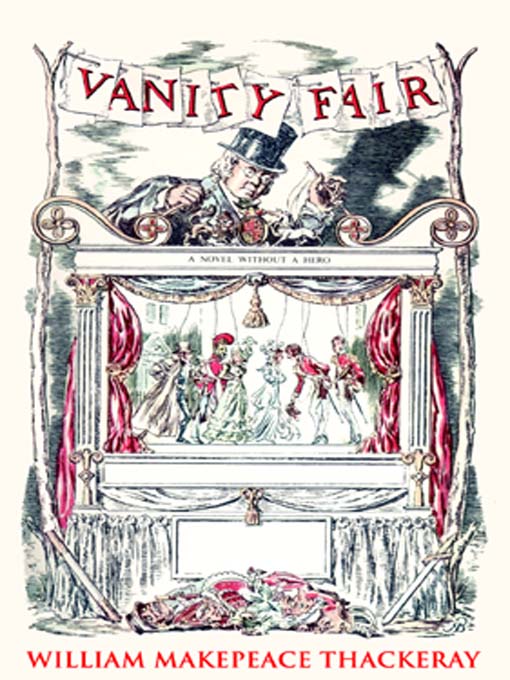

10. Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray (1847–48). The subtitle is “A Novel Without a Hero,” and never was a hero more unnecessary. In Becky Sharp, we find one of the most delicious heroines of all time. Sexy, resourceful, and duplicitous, Becky schemes her way through society, always with an eye toward catching a richer man. Cynical Thackeray, whose cutting portraits of society are hilarious, resists the usual punishments doled out to bad Victorian women and allows that the vain may find as much happiness in their success as the good do in their virtue.

%2B(1).jpg)