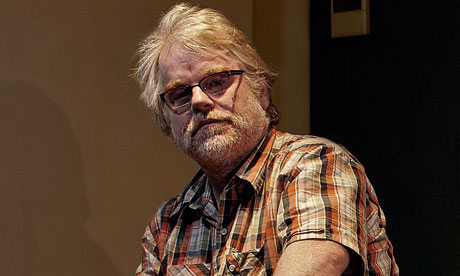

Philip Seymour Hoffman in 2011. Photograph: Desmond Muckian

To anyone who has heard the terrible news of Philip Seymour Hoffman's death in New York from a suspected overdose at the age of 46, I think one image recurs above all the others. It is his magnificent performance in Paul Thomas Anderson's The Master, playing the charismatic cult chief loosely derived from L Ron Hubbard — lordly and charismatic, convivial and yet sinister, insidious, insouciant.

And the most extraordinary moment was when he did his capering little dance, like a Shakespearian fool, in a wealthy drawing room, to "We'll Go No More A-Roving" and the scene took a hallucinatory turn, with all the onlookers appearing to be naked, submitting in that moment to his occult leadership. It was a scene only Hoffman could have carried off. For such a big man, he was elegant and sinuous.

In that movie he often resembled Joel Grey in Cabaret — but older, and pumped up to quarterback size. Anderson's direction brought out, in spades, all the qualities which made Hoffman such a formidable and at times even threatening presence: he looked like someone who would debate, seduce, or get in a physical fight at the drop of a hat. Maybe with the same person. And he often gave the impression of suppressing some deep well of anger, damming it and re-directing it into sexiness and charm.

A new generation of young moviegoers may associate Hoffman with the Hunger Games films, in which he plays the unsettling Plutarch Heavensbee, but he has been a vigorous and fiercely intelligent figure in the movies for nearly twenty years. His sheer physical might made him seem like the incredible Hulk compressed into the cerebral form of Dr Bruce Banner.

He got his Oscar, perhaps a little oddly, for playing the writer Truman Capote in 2005, a character who was on the verge of greatness with his reportage bestseller In Cold Blood. Capote was a very small man, and through sheer actorly suggestion, Hoffman appeared miraculously to lose 60% of his body mass to play the role: he looked tiny, like a little boy or a little old man, but dandyishly dressed, and with a vampirish knack of extracting the story he wanted out of anyone who made his acquaintance.

I personally first laid eyes on Hoffman the way a lot of people did: in Todd Solondz's excoriating black-comedy Happiness in 1998, when he played Allen, a deeply horrible but yet lonely guy who is addicted to making anonymous and sexually abusive phone calls. His psychotherapy reveals a chilling strain of violent fantasy, but also a poignant and pathetic need to be respectful and gentle to the people with whom he imagines himself to be in love. It was not Hoffman's screen debut, but it certainly made a shattering breakthrough impression. Here was a performer replete with darkness and danger, and yet a distinctive kind of cerebral high-mindedness also shone through.

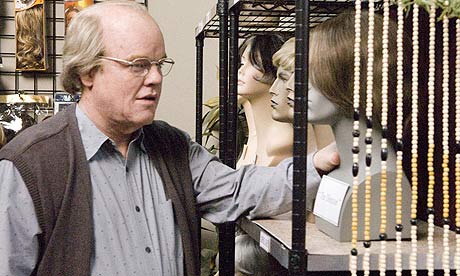

Philip Seymour Hoffman in Synecdoche, New York (2009). Photograph: PR

Philip Seymour Hoffman in Synecdoche, New York (2009). Photograph: PR

Almost immediately after that, he was icily cool, and brilliantly cast as the pudgy, glowering snob Freddie Miles in Anthony Minghella's The Talentesd Mr Ripley opposite Jude Law.

Hoffman found himself in one of the most brilliant American comedies of the noughties — some critics might even say of the most brilliant of modern times. And that was Charlie Kaufman's Synecdoche, New York (2008), playing Caden Cotard, the miserable theatre director who receives an apparently unlimited "genius" grant to work on whatever he wishes, and spends the money on building an entire city block, filling it with people who will improvise "real" 24/7 lives over a period of years, and so create a stunningly real theatrical happening that will go beyond the middlebrow world of culture. Of course, this project achieves a kind of Borgesian transcendence, and reality itself is questioned. Again, only Hoffman — that compressed, angry, passionate, questioning, unhappy screen presence — could have made it work.

He also gave a blisteringly good performance in Sidney Lumet's late masterpiece Before The Devel Knows You´re Dead in 2007, a gripping kind of heist-noir in which he plays a businessman who has been fiddling the company's accounts to finance his drug addiction and now figures on robbing a jewellery store to fill in the suspicious holes in the firm's books before the taxman inspects them.

Really: what an actor Philip Seymour Hoffman was. Almost every single one of his credits had something special about it. He was a cracking Lester Bangs in Cameron Crowe's Almost Famous in 2000, and gave one-hundred-degree proof performances in Anderson's Magnolia and Punch-Drunk Love. This was a performer who was at his very best, a character player who had the lithe sexuality and above-the-title watchability of a star. He had a lot more to give. It's desperately sad.

Read also

Obituaries / Philip Seymour Hoffman

Philip Seymour Hoffman / I was moody, mercurial

Philip Seymour Hoffman / A life in pictures

Philip Seymour Hoffman / I was moody, mercurial

Philip Seymour Hoffman / A life in pictures

+(1).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment