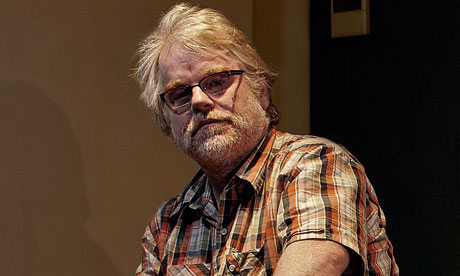

Philip Seymour Hoffman

'I was moody, mercurial... it was all or nothing'

He's made his name playing creeps and freaks. Now Philip Seymour Hoffman is directing his first film, Jack Goes Boating – and he's cast himself as the romantic hero. He tells Simon Hattenstone why it's time to stop beating up on himself

Philip Seymour Hoffman: 'I drank too much, so I stopped. I had no interest in drinking in moderation. I still don’t.' Photograph: Desmond Muckian

You want crippled communication, Philip Seymour Hoffman is your go-to man. You want all-round weirdos – red-faced, obese, heavy-breathing, sweating, self-loathing sickos – Hoffman's your man. There was a time when Masturbation could have been his middle name. Just look at the CV. As well as appearing in many of the best and bleakest movies of the past 15 years (often, unforgettably, for just a couple of minutes), there is a clear pattern. In Todd Solondz's Happiness he is the dysfunctional creep tossing himself off to strangers on the phone and convinced he is the least desirable man in the world. In Boogie Nights, he is a woeful hanger-on in a ginger bob, belly pouring over skin-tight denim shorts, hopelessly in love with porn star Dirk Diggler. Then there's Punch-Drunk Love, in which he's a monstrous blackmailer who runs phone sex lines, The Big Lebowski playing a greasy acolyte with a grotesque laugh, and Capote which won him an Oscar for his magnificent impression of Truman Capote – lazy lisp, preening narcissism and of course more than a hint of self-loathing.

Now he's directed his first film, Jack Goes Boating, in which he stars as the eponymous not-very-heroic hero. In a way, the film, based on a play Hoffman directed with the same cast, is familiar territory – Jack is a limo driver, single, hopeless, getting on, and so shy that, "Yeah… uhuh!" amounts to a monologue for him. But there's also a huge difference from the earlier characters. While they're almost always unsavoury and often irredeemable, Jack is a tongue-tied romantic so desperate to make his potential girlfriend happy that he learns to swim for her so he can take her boating and learns to cook for her so he can be the first man to have made a meal for her. It's a slow, quiet, endearing film.

Hoffman is a bear of a man – tall and wide, his belly tumbling over his belt just like in the films, and every bit as shambling. He looks like someone who never irons his shirts and frequently stains his trousers. While the likes of Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt do not seem to age, he has done so prematurely – his beard is white, hair going that way, chin doubled.

It's good to see that even as a director you cast yourself in a classic Hoffman role, I say. "Well, I guess so," he mumble-grumbles, before coming to an early pause. It's soon apparent that he finds constructing sentences every bit as hard as Jack. "I actually tried to get someone else to play the part, but we didn't have enough time and I couldn't get the person I wanted. So, yeah, it's a kind of role I've played before."

In what way? "What Jack's going through is something that influenced me more when I was younger. It's a real struggle to connect. When I was younger I really wanted to explore, you know, sexuality, and having to connect to people and how hard that is and how inadequate we all feel."

Now he's in his 40s, he says, there are new fixations – which also emerge in the new film. "I have family now. There are other things I think about now, which this film is about: is this the life I wanted? And if it's not, what are you going to do about it when you're not young any more?"

Nobody does self-loathing quite like you, I say. "Well, I think everyone struggles with self-love. I think that's pretty much the human condition, you know, waking up and trying to live your day in a way that you can go to sleep and feel OK about yourself. When I was younger I wanted to really show what it meant to have such doubt about yourself, such fear." He rubs his belly for inspiration. "It's not so much self-loathing as fear. You're just scared to venture out."

Was that fear rooted in you? "It was interesting. You know, I had girlfriends. I had insecurities and fears like everybody does, and I got over it. But I was interested in the parts of me that struggled with those things."

It's the rawness that he brought to those early parts that is so amazing. As he talks, I'm thinking of the slobbering, desperate lust of Boogie Nights and Happiness. Did girls back then always expect you to be terrible in bed? He laughs. "No."

Are you sure they did not expect the most abject sex ever?

"No, because they weren't watching my movies. These were girls I met, you know. No. To have someone characterise you from the parts you play, which is a job you do, is really hard to deal with sometimes because you're like... Heehee!" He giggles. It's a great laugh, full of life and humour. But I'm not sure it's a genuine laugh. I think there might be a warning in there.

Anyway, he says, all that stuff is ancient. Today, he's so much more interested in what it means to grow up and cope with what the world throws at you. He talks about more recent films such as Charlie Wilson's War (which saw him win another Oscar nomination for his portrayal of maveric CIA operative Gust Avrakotos) and the brilliantly bonkersSynecdoche in which he plays a theatre director who directs a play in which the characters improvise their life in real time till they die. In theIdes Of March (out on general release now) Hoffman plays an overcommitted campaign manager to George Clooney's idealistic presidential candidate. "These films are not so much about doubt, they are about attacking life with vigour, dealing with things at a different time of your life, when you don't have much time, and what you're going to do."

Hoffman, 44, grew up in New York and was a sporting boy with no aspirations to act. He played baseball and wrestled seriously till he was 15. His parents split up when he was nine, and his mother, Marilyn O'Connor, a civil rights activist and lawyer who worked her way up to judge, raised him after that. She sounds heroic, I say. He lights up. "She's a special woman. She had four kids and she split up with my dad, so there was just her in the house and she went to law school and became a lawyer and brought us up. My older sister had a lot to do with that, too. She also took me to the theatre when I was young, she loved sport, she was a big champion of me, and all the things I love now in my life my mum had a lot to do with."

And his father? "It was pretty much all Mum. I still had a relationship with my dad, but you know he lived somewhere else and he wasn't around a lot." He says his mother is the most positive can-do person he knows, and the most fun (not a word you'd easily associate with Hoffman). "My mum is incredibly intelligent. And talk about optimistic, she's always looked at the situation and said, 'Right, what do I want to do now?' She's incredible that way."

Has he got some of that? "I think so, but I'm also part of my father. To be fair to my dad, he is one of the brightest men I've ever met. My dad's more the brooding intellectual guy, more a slave to his emotions than my mum."

His mother encouraged him to join a drama group, he saw a girl there he fancied, stuck around for a small part in a play, and that was that. He loved the stage and never had plans to make movies. "I just thought I'd ride my bike to the theatre. That's what was romantic to me." He graduated in drama from New York University in 1989.

Soon afterwards he checked himself into rehab for alcohol and drug addiction, and has remained clean since. How serious was his problem? "It was pretty bad, you know what I mean. And I know, deep down, I still look at the idea of drinking with the same ferocity that I did back then. It's still pretty tangible."

What did he drink? "Anything. I went to rehab and you know…" He pulls at his arm impatiently. Did he feel he was having a good time? "I don't know, I was young, I drank too much, you know, so I stopped. You know what I mean, it's not really complicated. I had no interest in drinking in moderation. And I still don't. Just because all that time's passed doesn't mean maybe it was just a phase. That's you know, that's who I am."

A couple of years ago, the film writer David Thomson, a great fan of Hoffman, suggested the actor was not stretching himself. It seems a strange thing to say about someone famous for offbeat and challenging work. Yet Thomson has a point. The more discomfiting Hoffman is, the more he seems to be working in his comfort zone. What is so refreshing about Jack Goes Boating is that he plays a regular dysfunctional guy rather than a freaky dysfunctional guy. Thomson wondered why he didn't do a reverse De Niro, lose weight for jobs, surprise us with his svelteness.

Has he ever fancied being a conventional leading man? I expect him to laugh at the suggestion, tell me he wasn't built that way, but not at all. "Well, I don't think they exist any more. They're a myth now. I mean, do they make really good movies with leading men any more? I don't think the romantic leading guy is around any more, and I don't really think I would be that guy if he was." Why? "I don't think those are really interesting characters." And because he'd have to lose his belly? "Well, I've been without a belly before," he says tersely.

I've often wondered whether he seeks the roles out or they seek him out. "I don't know," he mumble-grumbles. "Because I think of other things like The Talented Mr Ripley. And it's a whole different thing; that guy's jumping from one bed to another, and he's barrelling in and venturing into a conversation with the nicest lady in the room." But even then there's a crazed intensity.

You look at the characters he's played and think he must come away so knackered and depressed by the end of the shoot. There is a story that one time a member of the crew asked him if he was having fun, and Hoffman looked at him as if he was bonkers. Fun? Are you kidding? "Well, that's something I said a long time ago and it was me being a little bit dramatic, but there's a truth to that, meaning that just because you like to do something doesn't mean you have fun doing it; and I think that's true about acting."

In the past, he says, roles would often get him down. For Capote, he spent three months learning how to be the writer. "I had to teach myself how to speak a certain way, and I had to get my body in a place where it would behave unselfconsciously in a way wildly different to how my body behaves. I was in training to get the muscles of my throat and body to support whatever emotional life I was going to bring to the character. That was very time-consuming." Back then he had only one child, now he has three and family has to come first. And that, he says, is another big change. "I got to remember to not kill myself, not beat myself up, not get too worked up about it."

Hoffman says he was so different when he started out. "I was more moody, more mercurial." As a young man, he felt he was what he was, and that was that. "Yes, there's that thing with being younger… You think it's all or nothing. You think all your eggs are in one basket when you're young. You're gambling. Whereas when you're older you realise you can reinvent; you think, this feeling I have is going to pass."

Blimey, I say, you seem to be suffering from a severe case of positivity. He smiles. "No, you know what I mean, this isn't everything, there will be another film, there will be another relationship, or I'll die and then I'll be dead. But if I'm alive I know life is going to keep throwing things at me." He walks slowly over to the window, lights a fag and puffs smoke out into the sunshine. And I leave him staring silently into the future, the bleakest optimist you ever did see.

Read also

Obituaries / Philip Seymour Hoffman

Philip Seymour Hoffman / Death of a master

Philip Seymour Hoffman / A life in pictures

Philip Seymour Hoffman / Death of a master

Philip Seymour Hoffman / A life in pictures

+(1).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment