When intellectuals cheer on fascism

Many thinkers supported fascist regimes in the 1930s, a precedent that is very disturbing today

Guillermo Altares

27 December 2024

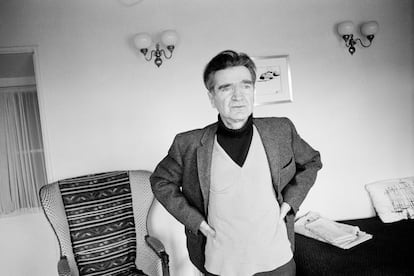

A famous photograph taken by Louis Monier in 1977 in one of the most beautiful squares in the Latin Quarter in Paris shows three great intellectuals of the 20th century whose influence continues to this day: the philosopher Emil Cioran, the historian of religions and novelist Mircea Eliade, and the playwright Eugène Ionesco. The first two had a very dark secret to hide: their sympathy for Romanian fascism in the 1930s and 1940s, their antisemitism, and their intellectual support for a regime responsible for the murder of tens of thousands of Jews. The third, the inventor of the theater of the absurd, of Jewish origin, survived the war and spent the rest of his life in France. They were very good friends in their youth, but their relationship was forever affected by Cioran and Eliade’s past.

The French essayist Alexandra Laignel-Lavastine, an expert on Eastern Europe, dedicated a fascinating work to the protagonists of that photo, Cioran, Eliade, Ionesco. L’oubli du fascisme (2002). Its title, “The oblivion of fascism,” resonates strongly today in this 21st century Europe in which so many parties — and not only those of the extreme right — try to hide, diminish, manipulate, what the great totalitarianisms of the 20th century represented for the world: total loss of freedoms, death, violence, destruction… “The philosopher’s support,” she writes in reference to Cioran, “for the Iron Guard, one of the most violent and antisemitic extreme right formations of the 1930s, lasted until the beginning of 1941.” Eliade maintained his support for this fascist movement when it had fully shown its true face.

From 1945 onward both reinvented their past, although, as the historian points out, they always lived in fear of it being revealed. Eliade, for example, was forced to cancel a trip to Jerusalem in 1973 because of his antisemitic past; Saul Bellow was criticized for being inspired by him in the novel Ravelstein and, although in a very collateral way, his name had a remote connection with the never-clarified murder of a Romanian professor on the campus of the University of Chicago in 1991. The journalist Ted Anton wrote a fascinating book about it, with a prologue by Umberto Eco, Eros, Magic, and the Murder of Professor Culianu (2013). It was always said that he never won the Nobel Prize because of his fascist past.

The terrible thing about this story is that Cioran and Eliade are two intellectuals who remain highly influential, republished, and read, and yet they allowed themselves to be seduced by the Iron Guard, an organization so violent and savage that it was dismantled by the regime itself after the Bucharest pogrom of January 1941. “Ionesco underlined it several times: European fascism in the interwar period was an invention of intellectuals,” writes Laignel-Lavastine, who explains that one of his most famous works, The Rhinoceros, told the story of an ideological contagion inspired by his friends, attracted by absolute evil.

The Iron Guard is back in the news because Romanian presidential candidate Călin Georgescu, an admirer of Russian President Vladimir Putin who has shaken up the country’s politics, has defended this fascist organization several times. And he is not the only right-wing leader who has tried to whitewash the totalitarianism of the 1930s, like the failed French presidential candidate Éric Zemmour, who went so far as to say that Vichy had saved French Jews when it contributed to their extermination.

In Spain, a leader of the far-right Vox party has been heard in Congress claiming that the post-civil war period was a time of peace and reconciliation; the offensive to whitewash Francoism is becoming more intense, not only among right-wing politicians, but also among historians and writers; conservative Popular Party leaders, from Alberto Núñez Feijóo to Isabel Díaz Ayuso, have protested against plans to commemorate (what a scandal!) the 50th anniversary of the dictator Franco’s death. All this speaks not of the past, but of the present, because the debate is no longer about whether fascism will return — that is a fact — but about what form it will take.

In 2004, the Romanian state commissioned an inquiry into the Holocaust in the country, which made it clear that it was not a purely Nazi undertaking, but that Romanian involvement was very intense. The foreword was written by the Romanian-born writer, Auschwitz survivor, and Nobel Peace Prize winner Elie Wiesel, who noted: “What is true for individuals is also true for communities. Repressed memories are dangerous because, when they surface, they can destroy what is healthy, debase what is noble, undermine what is elevated. A nation or a person can find various ways of dealing with its past, but none of them can ignore it. Why did so many citizens betray humanity, their own and ours, by choosing to persecute, torment, and murder defenseless and innocent men, women, and children?” In these dark times, Wiesel’s reflections are very pertinent, and the story of those intellectuals seduced by evil more disturbing than ever.

No comments:

Post a Comment