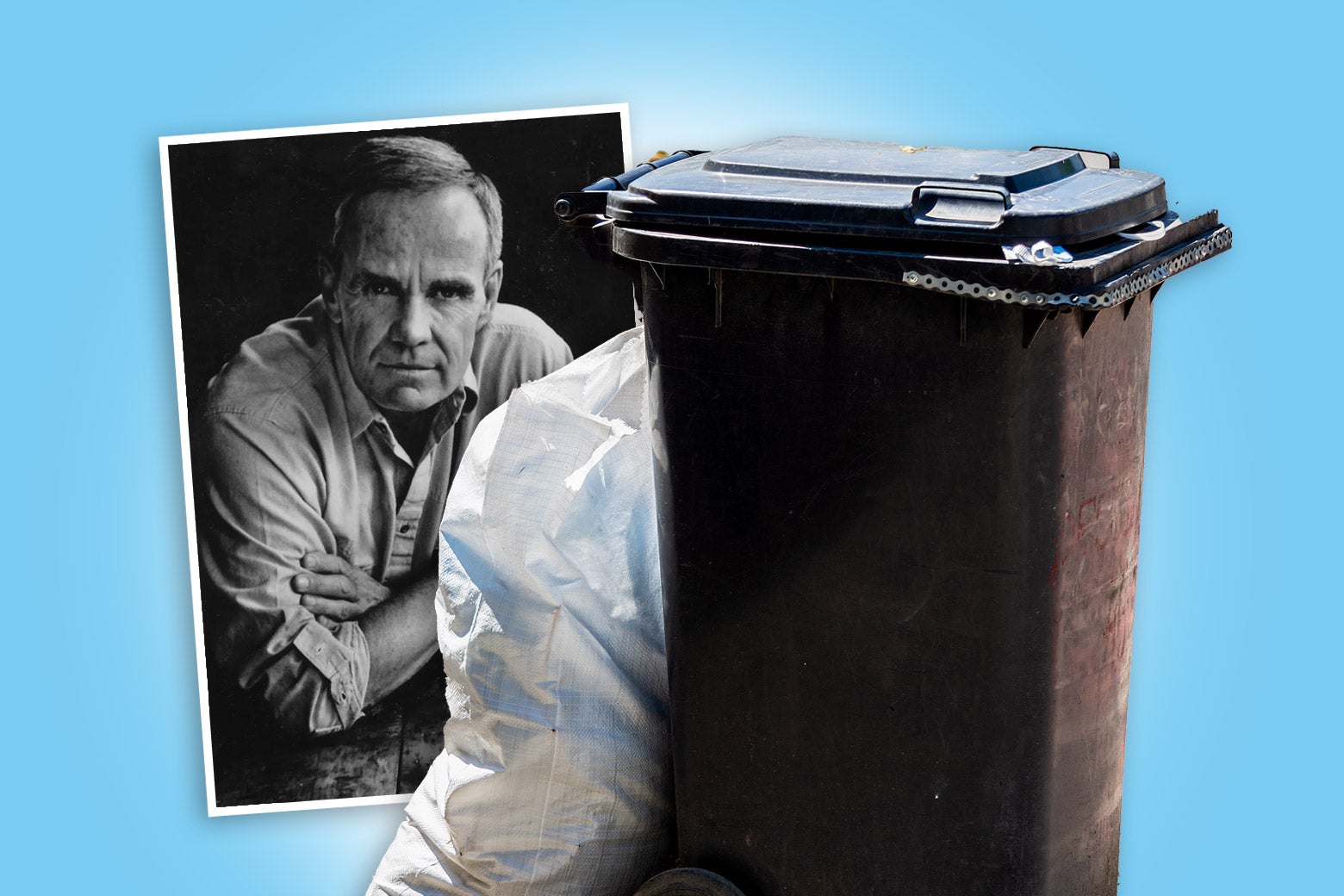

I Went Through Cormac McCarthy’s Trash

El Paso, 1996: a public-spirited stunt in a very different time.

R.I.P. Cormac McCarthy. I never met him, but I once had a relationship with him from rooting through his trash.

This was in the 1990s in the West Texas borderlands—in El Paso, where he lived at the time. El Paso by then was a sprawling city of hundreds of thousands, but so far off the grid of the metropolitan imagination that when I’d relocated there from the East Coast for grad school, my friends warned me there wouldn’t be any movie theaters. Of course there were, and when I went through McCarthy’s garbage I was not surprised to find he’d gone to one. Probably with a date: in the bag were two ticket stubs for Il Postino.

I saw movies, too; I’d stuck around El Paso, raised my kids there, and embraced the city. Besides border journalism I did immigrant civil rights activism. I became an assistant Girl Scout leader. I joined Planned Parenthood’s board of directors and the board of the public library. Like so many public resources in poverty-stricken El Paso, the struggling library was constantly trying to drum up money. A few writer luminaries lived in the city, and whenever we asked them to give benefit readings, people like Abraham Verghese showed up. But not “Cormac,” as we locals called him.

National stories about Cormac portrayed him as a Lone Ranger type, possibly a hermit, maybe residing in some cave in the desert. In El Paso, meanwhile, everyone knew he was living in the nicest part of town, attending trendy dinner parties, and dating a judge. The disconnect irritated me. He was often sighted at the vintage cafeteria Luby’s, eating the bargain lunch plate. Awestruck, people would shyly approach with their dog-eared copies of Blood Meridian and ask for an autograph. He always refused.

Sometimes my indignation made me feel like the asshole. I’d read All the Pretty Horses and some of Blood Meridian. I’m from a Texan Jewish family who, by the time I was born, had quietly struggled for five generations to be fully accepted by a state that once belonged to the Confederacy. I’d felt put off by the casual, Southern-WASP machismo and violence in Cormac’s work. Yet I was transfixed by the deep beauty of his language. “What does a writer owe to the world?” I asked myself. “Nothing! Nothing at all but to write.”

Still, I thought, the most famous literato in America was sucking his mojo—his descriptions of the landscape, the cowboy English, the Mexican Spanish, the horses!—from the borderlands. Yet he contributed nothing to his borderland community’s library. He was practically a natural resource, but he was going to waste. Could we utilize him for the commonweal without making demands on his time?

My eventual answer: Yes, by going through his trash.

I lived ten minutes from his house, a dirty-white adobe shaped like an indigenous, Southwestern bread oven. Trash pickup was on a certain day every week, and I learned that once it’s on the curb it’s public property. Cormac put his out the day before. On four or five occasions I drove up at twilight and dashed to the garbage cans, furtively glancing around to see if Cormac was anywhere in sight or if the neighbors were looking (he wasn’t; they weren’t). As I tossed the bags in my back seat then turned my key in the ignition, I felt brave and a little punky. Back home, the first time I picked through a bag I felt mean and small, looking at the balled-up Kleenexes and worn-out Dr. Scholl’s foot cushions.

As I write this after almost 30 years of not thinking about it, I know it may sound utterly, totally creepy. Indeed, many at the time were disgusted by what I was doing, including a lot of my friends. Others, also frustrated by Cormac’s lack of civic engagement, thought it was brilliant. The controversy remained mostly local; the Internet barely existed and we hardly knew about A.J. Weberman and his earlier obsession with Bob Dylan “garbology.” Many of Cormac’s discards seemed deliciously revealing.

I made a list of my favorite cullings and sent it to Harpers magazine. An editor loved it and prepared to run it in the “Readings” section. We were editing when suddenly the list was killed. My editor told me that top editors has seen the draft, had a shit fit, and denounced what I’d done as immoral.I just went down to my basement and found the list, after almost three decades. Here are some of the items:

One deer jawbone

Two hand-drawn sketches of late-1960s Buick Rivieras (Cormac had two such vehicles in his yard)

80-capsule jar, empty, Saw Palmetto berries

April and May 1996 issues of Popular Hot Rodding magazine

Spotlight, the bulletin of ultra-right, anti-Semitic conspiracy theorist Texe Marrs. (I always gave Cormac the benefit of the doubt … “Oh, he must be doing research!”)

Certified letter from Rent-A-Car, warning that he’s had the car for a month and if he doesn’t return it he will be charged with criminal embezzlement

Another sun-bleached deer jawbone

The newsletter of the Faulkner Society

April 1996 Worth magazine

Solicitation, Republican National Committee 1996 sustaining membership

Solicitation from the Conservative Book Club, “for people who are tired of liberal misinformation and propaganda”

Third deer jawbone

Audiobook packaging for Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus on cassette

Victoria’s Secret catalogue

Deer jawbone

My charity scheme for the library was to auction off the trash, or just give it away as favors, during an awards gala for the annual “Bad Cormac” writing contest—a cheeky local spin on the International Imitation Hemingway and Faux Faulkner competitions. Bad Cormac ran for two years; people paid a few bucks per 500-word entry to compete. I got dozens of submissions, from professional writers nationwide, to amateur adults across Texas, to local high school kids. Most of the entries riffed off of All the Pretty Horses, Cormac’s 1992 novel and his first bestseller. One first-place winner began: “In Terlingua a man walked up to John Grady Cole and said without preamble, my name is Perez, and am Commander of the Chili.”

At the awards ceremonies I tried to distribute some trash. Most people demurred. As for the library, they didn’t want the trash either, though they welcomed the contest money.

A few major publications mentioned the stunt, and then everyone, including me, forgot about it. Cormac eventually left El Paso for much more prosperous and trendy Santa Fe. Before he departed, I heard from a mutual friend that he knew I’d taken his garbage and thought that was amusing. This report of a sanguine response might seem improbable. But a generation ago, spirited ankle-biting in the boondocks could seem funny to the very famous person targeted because it mostly stayed local, with no Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or 24/7 news cycle to spread it to Manhattan.

Today, taking someone’s stuff off their curb in semi-darkness could get you shot, especially in Texas. Plus, the library would never hold a Bad Cormac contest proposed ad hoc by a private citizen. Today I’d have to go to the city council for approval. They would already have taken the “she’s creepy” position before they voted. Or I’d be told to write a grant, and if the funder learned about the trash I’d get an immediate rejection. The world is different today. Even if it weren’t, I’m older and possibly wiser. I wad my own Kleenex now. I need Dr. Scholl’s.

I don’t have anything of Cormac’s left. The deer jawbones sat for a time on my front porch, sun-bleached and horrible and Cormacian, until I couldn’t stand them any longer and threw them away—again.

SLATE

No comments:

Post a Comment